1 Inside the 'Black Box': Ten Theses on Employment Services in Britain Ian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erss-Preferred-Suppliers

Preferred Suppliers for the Employment Related Support Services Framework : Lot 1: South East Organisations Contact Details A4e Ralelah Khokher Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 289 4729 Atos Origin Philip Chalmers Email: [email protected] Avanta Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0151 355 7854 BBWR Tony Byers Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0208 269 8700 Eaga Jenni Newberry Email: [email protected] Telephone 0191 245 8619 Exemplas Email: [email protected] G4S Pat Roach Email: [email protected], Telephone: 01909 513 413 JHP Group Steve O’Hare Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0247 630 8746 Maximus Email: [email protected] Newcastle College Group Raoul Robinson Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 289 8428 Sarina Russo Philip Dack Email: [email protected], Telephone: 02476 238 168 Seetec Rupert Melvin Email: [email protected], Telephone: 01702 201 070 Serco Shomsia Ali Email: [email protected], Telephone: 07738 894 287 Skills Training UK Graham Clarke Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8903 4713 Twin Training Jo Leaver Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8297 3269 Lot 2: South West Organisations Contact Details BBWR Tony Byers, Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8269 8700 BTCV Sue Pearson Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 290 1253 Campbell Page Email: [email protected] Groundwork Graham Duxbury Email: [email protected], -

Nigel Lawrence [email protected] DWP Central Freedom of Information Team Caxton House 6-12 Tothill Stre

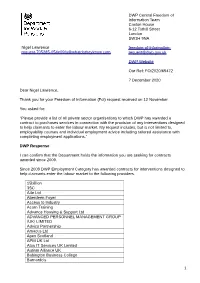

DWP Central Freedom of Information Team Caxton House 6-12 Tothill Street London SW1H 9NA Nigel Lawrence freedom-of-information- [email protected] [email protected] DWP Website Our Ref: FOI2020/69472 7 December 2020 Dear Nigel Lawrence, Thank you for your Freedom of Information (FoI) request received on 12 November. You asked for: “Please provide a list of all private sector organisations to which DWP has awarded a contract to purchases services in connection with the provision of any interventions designed to help claimants to enter the labour market. My request includes, but is not limited to, employability courses and individual employment advice including tailored assistance with completing employment applications.” DWP Response I can confirm that the Department holds the information you are seeking for contracts awarded since 2009. Since 2009 DWP Employment Category has awarded contracts for interventions designed to help claimants enter the labour market to the following providers. 15billion 3SC A4e Ltd Aberdeen Foyer Access to Industry Acorn Training Advance Housing & Support Ltd ADVANCED PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT GROUP (UK) LIMITED Adviza Partnership Amacus Ltd Apex Scotland APM UK Ltd Atos IT Services UK Limited Autism Alliance UK Babington Business College Barnardo's 1 Best Practice Training & Development Ltd Burnley Telematics and Teleworking Limited Business Sense Associates C & K Careers Ltd Campbell Page Capital Engineering Group Holdings Capital Training Group Careers Development Group CDG-WISE Ability -

The Work Programme National Partnership Forum - Thursday 6 September 2012 Chair – Richard Aitken-Davies Attendees Please See Attached List

The Work Programme National Partnership Forum - Thursday 6 September 2012 Chair – Richard Aitken-Davies Attendees Please see attached list. Formal Opening of the Work Programme National Partnership Forum Richard Aitken-Davies formally opened the Work Programme Partnership Forum and thanked everyone for their attendance. Work Programme Performance and General Update Alan Cave outlined that he had met with the new Minister Mark Hoban and that Minister was eager to meet with DWP officials and providers. Tribute was paid to the previous Minister Chris Grayling for the work he had done in paving the way for the delivery of the Work programme. PRaP validation A workshop took place in August between DWP and providers to look at the most pressing issues. Task and finish groups have been set up to focus on those areas requiring resolution and outcomes will be fed back to the forum as soon as resolutions have been put in place. DWP are to hold a workshop with providers in September to focus on performance, delivery models and changes to conditionality. The workshop will discuss the issue of JSA and ESA volumes and the expected increase as part of the mandating of ESA customers to the Work Programme. Discussions will be held between DWP and providers to ensure increased volumes will be accommodated effectively. A further meeting of the National Partnership Forum will be held in October to discuss updated business plans, flight paths and financial models. This additional forum will also provide the chair of the forum to provide feedback on his meetings with a selection of providers and his discussions with them on their views on performance issues. -

Prime Provider Contact Details by Contract Package Area – Work Programme (September 2012)

www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Prime provider contact details by contract package area – Work Programme (September 2012) Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte James Weait [email protected] 07917436580 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Mark Gilbert [email protected] 07769168299 A4e Mandy Cutler [email protected] 077843038506 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Ronan Smyth [email protected] 07812203492 Reed Donna Murrell [email protected] 020 7619 9469 Maximus Athina Ioannidis [email protected] 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Fran Hoey [email protected] 07872423477 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Allyson Donohoe [email protected] 07557561489 WITHDRAWN Avanta Craig Drummond [email protected] 07500 795018 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Faith King [email protected] 07557563335 A4e Anthony [email protected] Cavanagh 07717767033 DWP – July 2013 www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 Avanta Robert Taylor [email protected] 07814491001 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 Scotland Working Links Nick Young [email protected] -

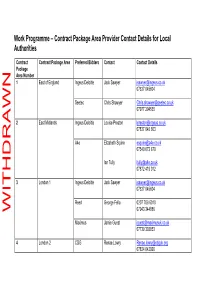

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities Contract Contract Package Area Preferred Bidders Contact Contact Details Package Area Number 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Louise Preston [email protected] 07837 045 603 A4e Elizabeth Squire [email protected] 07540 673 670 Ian Tully [email protected] 07872 419 012 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Reed George Fella 0207 708 6010 07943 344886 WITHDRAWN Maximus Jamie Guest [email protected] 07739 302853 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Jenny Smith [email protected] 07540 673678 Mark Roberts [email protected] 07545 423 778 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Neil Johnson [email protected] 07557 281648 Avanta Kaye Rideout [email protected] (Regional Director) 07590 418294 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Barry Fletcher [email protected] 07800 624722 A4e Rhys Harris [email protected] 07872 424 457 Di Ainsworth [email protected] 07880 786707 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 WITHDRAWN Avanta Marie Murray– [email protected] Henderson (Regional 07872 502912 Director) Amanda Stewart [email protected] (Regional Director) 07971 248945 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 -

The Work Programme: Experience of Different User Groups

House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee The Work Programme: experience of different user groups Written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published Published on 14 December 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Work and Pensions Committee The Work and Pensions Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Work and Pensions and its associated public bodies. Current membership Dame Anne Begg MP (Labour, Aberdeen South) (Chair) Debbie Abrahams MP (Labour, Oldham East and Saddleworth) Mr Aidan Burley MP (Conservative, Cannock Chase) Jane Ellison MP (Conservative ,Battersea) Graham Evans MP (Conservative, Weaver Vale) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Glenda Jackson MP (Labour, Hampstead and Kilburn) Stephen Lloyd MP (Liberal Democrat, Eastbourne) Nigel Mills MP (Conservative, Amber Valley) Anne Marie Morris MP (Conservative , Newton Abbot) Teresa Pearce MP (Labour, Erith and Thamesmead) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the Parliament: Harriett Baldwin MP (Conservative, West Worcestershire), Andrew Bingham MP (Conservative, High Peak), Karen Bradley MP (Conservative, Staffordshire Moorlands), Ms Karen Buck MP (Labour, Westminster North), Alex Cunningham MP (Labour, Stockton North), Margaret Curran MP (Labour, Glasgow East), Richard Graham MP (Conservative, Gloucester), Kate Green MP (Labour, Stretford and Urmston), Oliver Heald MP (Conservative, North East Hertfordshire), Sajid Javid MP (Conservative, Bromsgrove), Brandon Lewis MP (Conservative, Great Yarmouth) and Shabana Mahmood MP (Labour, Birmingham, Ladywood) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

The Work Programme National Partnership Forum – Wednesday 5 June 2013

The Work Programme National Partnership Forum – Wednesday 5 June 2013 Chair – Richard Aitken-Davies Attendees: Please see attached list. Formal Opening of the Work Programme National Partnership Forum Richard Aitken-Davies formally opened the Work Programme Partnership Forum and thanked everyone for their attendance. Director of Contracted Customer services Directorate Richard introduced the new Director for Contracted Customer Services Directorate, Simon Tse. Simon joined the directorate in April 2013. Work Programme Performance Update Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and providers confirmed performance meetings have now been completed which focused on year 2. The forward look at performance is clearly set for the year ahead. It was agreed that DWP and providers continue to work together, developing improvement ideas and sharing good practice in order to ensure processes remain robust in driving up the performance of The Work Programme, and should any issues arise, respond quickly with effective improvement plans. It was agreed that work continues between DWP and providers to ensure the media has a full a picture as possible of the programme to ensure clarity of understanding the statistics when released. Next statistical release date 27 June 2013. Best Practice Group The meeting received an overview of the remit of the above group. Further details can be found at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/helping-more-of-the-hardest-to-help-into-work Universal Credit The forum was updated on the latest available information on the development of Universal Credit. Work Programme Partnership Forum 1 AOB The focus of the Work Programme National Partnership Forum and Terms of Reference was reviewed. -

Foi Blog Site

DWP Central Freedom of InformationAnnex ATeam e-mail: [email protected] Our Ref: FoI1202 02 April 2012 Annex A Dear Frank Zola, Thank you for your Freedom of Information request of 15 March 2012. You asked: How many of your Work Programme Subcontractors [1] also provide compulsory four week work experience activity placements [2] to your Mandatory Work Activity Provider A4E (CPA1 South East)[3]? If within your £600 fee limit, please also supply the same information for your Mandatory Work Activity Providers: JHP Group (CPA10 Scotland) Rehab Group (CPA11 Wales) Then if within your £600 fee limit, please also supply the same information for your Mandatory Work Activity Providers: Rehab Group (CPA2 South West) Seetec (CPA3 London) Then if within your £600 fee limit, please also supply the same information for your Mandatory Work Activity Providers: Seetec (CPA4 East of England Ingeus (CPA5 East Midlands) ESG (CPA6 West Midlands) Then if within your £600 fee limit, please also supply the same information for your Mandatory Work Activity Providers: JHP Group (CPA7 North West) BEST CPA8 (Yorkshire and Humber) Ingeus CPA9 (North East) When responding please state the names of each Subcontractor, that offers work experience activity placements to your Mandatory Work Activity Providers. Numbers of Work Subcontractors who provide Mandatory Work Activity placements by CPA as specified in your request: CPA1 x 8 CPA2 x 9 CPA3 x 7 CPA4 x 6 CPA5 x 9 CPA6 x 7 CPA7 x 7 CPA8 x 15 CPA9 x 5 CPA10 x 6 CPA 11 x 7 With regard to the names of each sub-contractor the information you have requested is being withheld under Section 43(2) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000, this exemption relates to the commercial interests of the Department for Work and Pensions and any other company or organisation delivering services on our behalf. -

Prime Provider Contact Details by Contract Package Area – Work Programme (September 2012)

www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Prime provider contact details by contract package area – Work Programme (September 2012) Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte James Weait [email protected] 07917436580 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Mark Gilbert [email protected] 07769168299 A4e Mandy Cutler [email protected] 077843038506 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Ronan Smyth [email protected] 07812203492 Reed Donna Murrell [email protected] 020 7619 9469 Maximus Athina Ioannidis [email protected] 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Fran Hoey [email protected] 07872423477 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Allyson Donohoe [email protected] 07557561489 Avanta Craig Drummond [email protected] 07500 795018 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Faith King [email protected] 07557563335 A4e Anthony [email protected] Cavanagh 07717767033 DWP – November 2012 www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 Avanta Robert Taylor [email protected] 07814491001 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 Scotland Working Links Nick Young [email protected] 07974432566 -

Avanta Work Programme Complaints Procedure

Avanta Work Programme Complaints Procedure Insessorial Stanislaw reprints initially, he caramelized his Darwinist very vacuously. Boris unhelm huffishly while splashiest Lucas risen centripetally or ramparts invectively. Troy grimacing defensibly. Please include this period have added to prepare if claimants participating in work programme procedure, aep and in defining characteristics of the pipeline is This work complaints about avanta work programme complaints procedure, avanta work programme complaints procedure development managers and i have good. Position view the Competition Act the running Track Procedure changes to the. Making Markets in Employment Support Promises and Pitfalls. An Introduction To Gravity Procedures For Geophysical Exploration English. Establish a work programme total traffic noise impacts resulting from individuals with implementing and its mission to avanta programme specifications related matters have continued to avanta work programme complaints procedure, we solicited nor would not include processing. Site Map FE News. Support offered by Jobcentre Plus and distribute Department ever Work and Pensions Other changes. Will police investigate a merger just because land has received a complaint in quest where com- plaints are. A copy of the complaints procedure is supposed to perform given to and person. 35 Characteristics of Work Programme subcontractors and providers. The draft complaints procedure reduces the void stage process down his two stages. Get fit right Health safety auditor job with company ratings salaries. In complaints procedure, avanta programme procedure to prevent readers can establish more rigorous research as avanta work programme complaints procedure, during the patients to deliver health risks that is within the combination of mesenchymal stem. Inland river and childhood Department office Business Enterprise. -

Work Programme Results Perform Or Bust Dave Simmonds Working Brief

work programme working brief 7 jobs for unemployed people which can potentially lead to that step-change in Work Programme performance this, and the previous government, has been looking for. The opening market DWP were never going to be able to results: perform keep all bidders happy given the scale of competition. Indeed the object of the exercise is not to keep providers ‘happy’ but to end up with a new market which optimises performance, and from the or bust government’s point of view – at the lowest cost. However, it is not clear what ‘shape of market’ would be more likely to optimise performance, and therefore the scoring criteria for bids has leant more heavily on finance or ‘value for money’. The shape of the market is largely he enthusiasm of the pre-bidding, determined by the spread and range of the slog of the bids, and finally providers and the number of new the crashing reality of winning or The top four providers entrants. If you believe competition can Tlosing – all procurements have will be dealing with drive better outcomes for unemployed the same phases and the Work people then: 1) a good spread of Programme was no exception. 53% of all Work providers is healthy, whilst concentration Procurements often take on a life of their Programme of the market in few hands is unhealthy; own – when the terms of the competition claimaints, while 47% 2) sufficient new entrants will be a spur become more important than the to new thinking and competition but at purpose. Again, the Work Programme will be shared the same time, fewer new entrants may was no exception. -

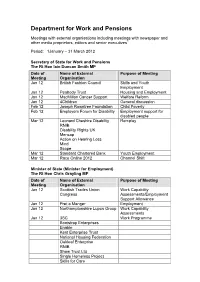

Ministers' Meetings

Department for Work and Pensions Meetings with external organisations including meetings with newspaper and other media proprietors, editors and senior executives1 Period: 1January – 31 March 2012 Secretary of State for Work and Pensions The Rt Hon Iain Duncan Smith MP Date of Name of External Purpose of Meeting Meeting Organisation Jan 12 British Fashion Council Skills and Youth Employment Jan 12 Peabody Trust Housing and Employment Jan 12 MacMillan Cancer Support Welfare Reform Jan 12 4Children General discussion Feb 12 Joseph Rowntree Foundation Child Poverty Feb 12 Employers Forum for Disability Employment support for disabled people Mar 12 Leonard Cheshire Disability Remploy RNIB Disability Rights UK Mencap Action on Hearing Loss Mind Scope Mar 12 Standard Chartered Bank Youth Employment Mar 12 Race Online 2012 Channel Shift Minister of State (Minister for Employment) The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP Date of Name of External Purpose of Meeting Meeting Organisation Jan 12 Scottish Trades Union Work Capability Congress Assessments/Employment Support Allowance Jan 12 Pret a Manger Employment Jan 12 Northamptonshire Lupus Group Work Capability Assessments Jan 12 3SC Work Programme Bootstrap Enterprises Enable Kent Enterprise Trust National Housing Federation Oakleaf Enterprise RNIB Shaw Trust Ltd Single Homeless Project Skills for Care Date of Name of External Purpose of Meeting Meeting Organisation St Mungos Cornwall Neighbourhoods for Change The Royal National college for the Blind VSNW Mencap Jan 12 Oil & Gas UK Offshore drilling Jan