The Work Programme: Experience of Different User Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erss-Preferred-Suppliers

Preferred Suppliers for the Employment Related Support Services Framework : Lot 1: South East Organisations Contact Details A4e Ralelah Khokher Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 289 4729 Atos Origin Philip Chalmers Email: [email protected] Avanta Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0151 355 7854 BBWR Tony Byers Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0208 269 8700 Eaga Jenni Newberry Email: [email protected] Telephone 0191 245 8619 Exemplas Email: [email protected] G4S Pat Roach Email: [email protected], Telephone: 01909 513 413 JHP Group Steve O’Hare Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0247 630 8746 Maximus Email: [email protected] Newcastle College Group Raoul Robinson Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 289 8428 Sarina Russo Philip Dack Email: [email protected], Telephone: 02476 238 168 Seetec Rupert Melvin Email: [email protected], Telephone: 01702 201 070 Serco Shomsia Ali Email: [email protected], Telephone: 07738 894 287 Skills Training UK Graham Clarke Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8903 4713 Twin Training Jo Leaver Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8297 3269 Lot 2: South West Organisations Contact Details BBWR Tony Byers, Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8269 8700 BTCV Sue Pearson Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 290 1253 Campbell Page Email: [email protected] Groundwork Graham Duxbury Email: [email protected], -

Bridges Into Work Overview

The Bridges into Work project started in January 2009. Its aim is to support local people gain the skills and confidence to help them move towards employment. The project is part funded by the Welsh European Funding Office across 6 local authorities in Convergence areas of South Wales – Merthyr Tydfil , Rhondda Cynon Taf, Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent, Bridgend and Caerphilly. In Merthyr Tydfil the project is managed and implemented by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council, which has enjoyed massive success with its recent venture The Neighbourhood Learning Programme. It has helped to engage local people to secure full time employment and to progress onto further learning in recent years. Carrying on from the achievement is the Neighbourhood Learning Centre, Gurnos and the newly established Training Employment Centre in Treharris. Both centres seek to engage with local people from all parts of Merthyr Tydfil and fulfil the Bridges into Work objective of providing encouragement, training, advice and guidance for socially excluded people with the view to get them back into work. The Neighbourhood Learning Centre has a range of training facilities covering a variety of sectors including plumbing, painting and decorating, carpentry, bricklaying, plastering, retail, customer service and computer courses. There are a team of experienced tutors who deliver training for local people within the community. Bridges into Work successfully delivered a Pre-Employment course for Cwm Taf Health Trust to recruit Health Care Assistants. With the help and support of the Neighbourhood Learning Pre-Employment Partnership fronted by the Bridges into Work Programme which includes organisations such as Voluntary Action Merthyr Tydfil, Remploy, Working Links, Shaw Trust, A4E, JobCentre Plus and JobMatch successfully provided and supported participants interested in becoming Health Care Assistants. -

Nigel Lawrence [email protected] DWP Central Freedom of Information Team Caxton House 6-12 Tothill Stre

DWP Central Freedom of Information Team Caxton House 6-12 Tothill Street London SW1H 9NA Nigel Lawrence freedom-of-information- [email protected] [email protected] DWP Website Our Ref: FOI2020/69472 7 December 2020 Dear Nigel Lawrence, Thank you for your Freedom of Information (FoI) request received on 12 November. You asked for: “Please provide a list of all private sector organisations to which DWP has awarded a contract to purchases services in connection with the provision of any interventions designed to help claimants to enter the labour market. My request includes, but is not limited to, employability courses and individual employment advice including tailored assistance with completing employment applications.” DWP Response I can confirm that the Department holds the information you are seeking for contracts awarded since 2009. Since 2009 DWP Employment Category has awarded contracts for interventions designed to help claimants enter the labour market to the following providers. 15billion 3SC A4e Ltd Aberdeen Foyer Access to Industry Acorn Training Advance Housing & Support Ltd ADVANCED PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT GROUP (UK) LIMITED Adviza Partnership Amacus Ltd Apex Scotland APM UK Ltd Atos IT Services UK Limited Autism Alliance UK Babington Business College Barnardo's 1 Best Practice Training & Development Ltd Burnley Telematics and Teleworking Limited Business Sense Associates C & K Careers Ltd Campbell Page Capital Engineering Group Holdings Capital Training Group Careers Development Group CDG-WISE Ability -

Dear Mr Kelly, Freedom of Information Request Reference Number FOI 267

Dear Mr Kelly, Freedom of Information Request reference number FOI 267 We write further to the Court of Appeal judgment in Department for Work and Pensions v Information Commissioner & Frank Zola, to which your case was joined. The judgment was handed down on Wednesday 27 July 2016. The Court of Appeal has upheld the decision of the First-tier Tribunal in Department of Work and Pensions v Information Commissioner & Frank Zola [2013]. We write, in light of the judgment, in response to your Freedom of Information request of 2012. In your request you asked for: “the names of all organizations who have provided work boost placements, work experience, or other unpaid work activity to customers of Seetec within Contract Package Area 4 (East London) within the past 12 months. In cases where a subcontractor to Seetec was involved, please note which subcontractor or subcontractors were involved with each organization.”. Contract Package Area 4 (East London) is a Work Programme Contract Package Area. Three providers deliver the Work Programme in Contract Package Area 4 (East London): Peopleplus, Shaw Trust and Seetec. You asked for the organisations that provided work placements to Seetec. DWP contracts with prime providers, such as Seetec, to source organisations who delivered the Work Programme. Some of these providers may have sent claimants on work experience placements. DWP does not contract directly with these work experience placement hosts. We have enclosed all the information we were given by Seetec in relation to your request. A copy of this letter has also been sent to the Information Commissioner’s Office. -

1 Inside the 'Black Box': Ten Theses on Employment Services in Britain Ian

1 Inside the ‘Black Box’: Ten theses on Employment Services in Britain Ian Greer, Lisa Schulte, and Graham Symon Paper presented at the University of Greenwich, June 2014 Summary This report presents initial findings on the UK from a project funded by the Hans-Boeckler-Foundation on the marketisation of employment services in the UK, Germany, and Denmark. We present findings from interviews with front-line staff, managers, claimants groups, and trade unionists, as well as publicly available statistics and reports. We convey what is distinctive about the UK by developing ten theses on the so-called ‘Black Box’, the UK’s highly centralised and privatized approach to organizing services. The Black Box is privatized but keeps marketisation within strict limits. The Black Box involves centralised and contracted-out government contracting. One result is the outsourcing of the DWP’s relations with the voluntary sector and local government to the private sector. The Black Box repackages the risk of policy failure as a financial risk, to be managed with an eye to profitability. The Black Box is dominated by a few ‘prime contractors’, for which scale and scope are advantages. This kind of contracting requires both access to capital and large-scale management capacity. Most organizations in the Black Box operate in a volatile market segment of subcontractors, where contract termination is more common for public and nonprofit providers than for for- profit providers. The Black Box matters for the character of services. It contains strong tendencies toward creaming and parking, despite minimum service requirements and differential pricing. Performance management by the prime contractors is tight and sophisticated. -

Work Programme Supply Chains

Work Programme Supply Chains The information contained in the table below reflects updates and changes to the Work Programme supply chains and is correct as at 30 September 2013. It is published in the interests of transparency. It is limited to those in supply chains delivering to prime providers as part of their tier 1 and 2 chains. Definitions of what these tiers incorporate vary from prime provider to prime provider. There are additional suppliers beyond these tiers who are largely to be called on to deliver one off, unique interventions in response to a particular participants needs and circumstances. The Department for Work and Pensions fully anticipate that supply chains will be dynamic, with scope to flex and evolve to reflect change within the labour market and participant needs. The Department intends to update this information at regular intervals (generally every 6 months) dependant on time and resources available. In addition to the Merlin standard, a robust process is in place for the Department to approve any supply chain changes and to ensure that the service on offer is not compromised or reduced. Comparison between the corrected March 2013 stock take and the September 2013 figures shows a net increase in the overall number of organisations in the supply chains across all sectors. The table below illustrates these changes Sector Number of organisations in the supply chain Private At 30 September 2013 - 367 compared to 351 at 31 March 2013 Public At 30 September 2013 - 128 compared to 124 at 30 March 2013 Voluntary or Community (VCS) At 30 September 2013 - 363 compared to 355 at 30 March 2013 Totals At 30 September 2013 - 858 organisations compared to 830 at March 2013. -

The Work Programme National Partnership Forum - Thursday 6 September 2012 Chair – Richard Aitken-Davies Attendees Please See Attached List

The Work Programme National Partnership Forum - Thursday 6 September 2012 Chair – Richard Aitken-Davies Attendees Please see attached list. Formal Opening of the Work Programme National Partnership Forum Richard Aitken-Davies formally opened the Work Programme Partnership Forum and thanked everyone for their attendance. Work Programme Performance and General Update Alan Cave outlined that he had met with the new Minister Mark Hoban and that Minister was eager to meet with DWP officials and providers. Tribute was paid to the previous Minister Chris Grayling for the work he had done in paving the way for the delivery of the Work programme. PRaP validation A workshop took place in August between DWP and providers to look at the most pressing issues. Task and finish groups have been set up to focus on those areas requiring resolution and outcomes will be fed back to the forum as soon as resolutions have been put in place. DWP are to hold a workshop with providers in September to focus on performance, delivery models and changes to conditionality. The workshop will discuss the issue of JSA and ESA volumes and the expected increase as part of the mandating of ESA customers to the Work Programme. Discussions will be held between DWP and providers to ensure increased volumes will be accommodated effectively. A further meeting of the National Partnership Forum will be held in October to discuss updated business plans, flight paths and financial models. This additional forum will also provide the chair of the forum to provide feedback on his meetings with a selection of providers and his discussions with them on their views on performance issues. -

A Helping Hand Enhancing the Role of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise Organisations in Employment Support Programmes in London October 2015 Appendix 1

Appendix 1 Economy Committee A Helping Hand Enhancing the role of voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations in employment support programmes in London October 2015 Appendix 1 Economy Committee Members Fiona Twycross (Chair) Labour Stephen Knight (Deputy Chair) Liberal Democrat Tony Arbour Conservative Jenny Jones Green Kit Malthouse MP Conservative Murad Qureshi Labour Dr Onkar Sahota Labour Committee contact Simon Shaw Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 6542 Media contact: Lisa Lam Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 4067 Appendix 1 Contents Chair’s foreword ................................................................................................. 1 Executive summary ............................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 2. The challenges to VCSE organisations’ involvement in employment programmes........................................................................................................ 9 3. What can be done to address the challenges to VCSE organisations’ involvement? .................................................................................................... 14 4. Devolution of employment programmes ................................................. 21 Appendix 1 – Recommendations ...................................................................... 26 Appendix 2 – Major employment programmes .............................................. -

DWP's Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health

DWP’s Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (Release 5 October 2020) ERSA is pleased to be able to inform you of the organisations on Tier 1 and Tier 2 of the DWP Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (CAEHRS). In total the DWP received submissions from 61 organisations with a total of 171 compliant submissions across the 7 regional lots. Overall, this has resulted in a total of 28 organisations being awarded a place on CAEHRS, 21 of which have multiple places and 7 have single awards. As set out during this competition the design of CAEHRS allows the department to offer further places they become available. The department does not currently have any plans to undertake further activity at this time but will formally notify the market as appropriate. Those that have been unsuccessful on this occasion are able to bid for future opportunities on CAEHRS. As communicated previously CAEHRS is already planned to be used for Scotland JETS delivery in Regional Lot 7 later this month and the Long-term unemployment programme that subject to further decisions will be outlined shortly. ERSA’s Chief Executive, Elizabeth Taylor said “This announcement is welcomed by the sector. ERSA is scheduling a series of events to provide more information about the successful organisations and the DWP’s plans, these events will keep the sector informed, build partnerships, and enable collaboration”. ERSA is running a series of Meet the Primes events, the first of which will be on Friday 23 October at 1pm. This will be followed by ERSA Member Forums based on the 7 CPA/ regional lot areas. -

Prime Provider Contact Details by Contract Package Area – Work Programme (September 2012)

www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Prime provider contact details by contract package area – Work Programme (September 2012) Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte James Weait [email protected] 07917436580 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Mark Gilbert [email protected] 07769168299 A4e Mandy Cutler [email protected] 077843038506 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Ronan Smyth [email protected] 07812203492 Reed Donna Murrell [email protected] 020 7619 9469 Maximus Athina Ioannidis [email protected] 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Fran Hoey [email protected] 07872423477 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Allyson Donohoe [email protected] 07557561489 WITHDRAWN Avanta Craig Drummond [email protected] 07500 795018 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Faith King [email protected] 07557563335 A4e Anthony [email protected] Cavanagh 07717767033 DWP – July 2013 www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 Avanta Robert Taylor [email protected] 07814491001 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 Scotland Working Links Nick Young [email protected] -

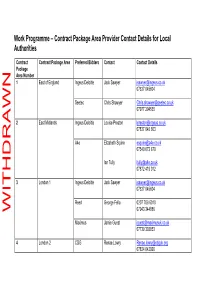

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities Contract Contract Package Area Preferred Bidders Contact Contact Details Package Area Number 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Louise Preston [email protected] 07837 045 603 A4e Elizabeth Squire [email protected] 07540 673 670 Ian Tully [email protected] 07872 419 012 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Reed George Fella 0207 708 6010 07943 344886 WITHDRAWN Maximus Jamie Guest [email protected] 07739 302853 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Jenny Smith [email protected] 07540 673678 Mark Roberts [email protected] 07545 423 778 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Neil Johnson [email protected] 07557 281648 Avanta Kaye Rideout [email protected] (Regional Director) 07590 418294 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Barry Fletcher [email protected] 07800 624722 A4e Rhys Harris [email protected] 07872 424 457 Di Ainsworth [email protected] 07880 786707 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 WITHDRAWN Avanta Marie Murray– [email protected] Henderson (Regional 07872 502912 Director) Amanda Stewart [email protected] (Regional Director) 07971 248945 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 -

Tips for People Who Are Looking for Work

Tips for people who are looking for work Where to go Staff at your local Job Centre Plus will be able to help you find work, give you advice on benefits and also sign post you to organisations for support in finding a job. www.gov.uk Voluntary work Volunteering can offer so much. If you want or need to develop skills, want to see what it would be like to work in a specific area or just want to give something back to the community, voluntary work is well worth looking in to. Many local towns and cities have voluntary bureaus such as the Voluntary Skills Council. These organisations would be willing to sign post you to voluntary opportunities. Voluntary work should not affect your benefits. (please seek professional advice about this) www.do-it.org – This is a web site which offers opportunities in your area Local colleges Many local colleges run employability courses to help you get started and help you to develop the skills you need to move closer to the world of work. Local colleges have neighbourhood sites which may be in your area. They offer excellent opportunities to develop and gain new skills. www.colleges-uk.co.uk - This is a website that will help you find a college that is local to you. Work Choice Work Choice can help you get and keep a job if you have a disability or an ongoing health condition and find it hard to work. The type of support you will get depends on what you need - It’s different for everyone.