May 5 1978 -2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passionate Pursuits

Fall/Winter ’08/’09 Passionate Pursuits Friends’ Central Directions Fall/Winter ’08/’09 2008-2009 Board of Trustees From the Headmaster: Ann V. Satterthwaite, Clerk Peter P. Arfaa James B. Bradbeer, Jr. Adrian Castelli Dear Friends, Kenneth Dunn Kaye Edwards I have just finished previewing the George Elser feature articles for this edition of Jean Farquhar ’70 Victor Freeman ’80 Directions, and if you can set aside the Christine Gaspar ’70 time, I believe you will be as fascinated as Robert Gassel ’69 I have been by the collecting passions of Edward Grinspan William Fordyce ’52, Joanna Schoff ’51, Walter Harris ’75 Sally Harrison Rich Ulmer ’60, Rachel Newmann Karen Horikawa ’77 Schwartz ’89, and current student Blake Deborah Hull Bortnick ’13. In her introduction, our Michael C. Kelly editor, Rebecca Anderson, sheds some Matthew S. Levitties ’85 Craig Lord light on possible motives for collecting Hillard Madway and provides additional examples of col - Ed Marshall ’68 lectors currently devoting time and effort Carol Mongeluzzi Suzanne Morrison to a favorite pastime in the School’s midst By all accounts, William Fordyce was Jeffrey Purdy and for our community’s benefit. The a very private man, and after his gradua - Lawrence S. Reichlin interest a collector displays in sharing a tion he was mainly absent from our com - Marsha Rothman collection is particularly gratifying to a munity. In the end, though, through his Jonathan Sprogell James Wright School that both encourages and sup - thoughtful and generous gift he returned Barbara M. Cohen, Emerita ports individual interests and values to the School and revealed an important Joanna Haab Schoff ’51, Emerita connections among members of the part of himself. -

Tina Tina 79 IMGSRCRU

1 / 3 Tina, Tina (79) @iMGSRC.RU a visual object or experience consciously created through an expression of skill or imagination. The term art encompasses diverse media such as painting, ...Missing: (79) | Must include: (79). Nov 9, 2013 — I actually found this Pumpkin Coffee Cake from Tina's Chic Corner BEFORE you all picked it as your favorite by clicking it ... 32x32-Stars-79-TW.. Jul 13, 2015 — As an account executive for CORnerstone Risk Solutions, a subsidiary of The IMA Financial Group, Tina will work with self- insured clients to .... Oct 12, 2013 — German Chocolate Cake Doughnuts from Tina's Chic Corner are a really great excuse to buy a doughnut pan. I mean ... 32x32-Stars-79-TW.. Place the table in the DIV with id="p2_out"> and after the table show: the state name with the .... .... Tina Turner: Tina Live! CD . ... Florence joined the District in 1992 as a physical education teacher at the Middle School. Tina McCauley, assistant principal at Lomond Elementary School since .... Matthijs (teambeurnaut) · Bitwala Security (team_bitwala) · Tina (teamblue) · Alan Barber (team-cadencelabs) · peter yaworski (teamcanada) · If Only Justin was .... Jul 10, 2007 — The sale was handled by Tina Adrian of Re-Max Classic in cooperation with Chris Kennedy of Charles Burt Homefolks. Randolph Brownell and .... Nov 21, 2017 — ... href="https://ru.atlassian.com/legal/customer-agreement" ... 20px;">. ... 79XybQdSii0f+Pyr5TosJDxoqIUV26jNO5NL60GfmmtYzO4TucVWUR5M/gnFeVbMl+ ... 1 Sep 2014 16:31:22 +0000 Reply- To: Tina Minchella Sender: ... from guest editors Zhi-Xue Zha= ng, (George) Zhen Xiong Chen, Ya-Ru Chen, and Soon Ang. ... target=3D"_blank">. Contributors: Essan Ni Jirman, Tina Brand, P. -

Tina Theory: Notes on Fierceness

Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 24, Issue 1, Pages 71–86 Tina Theory: Notes on Fierceness Madison Moore Yale University Touching Queerness Everything I know about being queer I learned from Tina Turner. More specifically, you might say that Ike and Tina’scover of “Proud Mary”— the soundtrack of my childhood—taught me, through camp performance, how to be a “Mary.” During the holiday parties at my great-grandmother Lucille “Big Momma” Jones’ house, for as long as I can remember, we kids ended up in the “Children’s Room” so the grown folks could curse, drink whiskey, smoke, laugh, and be as loose as they felt. The “Children’s Room” was not that special. It was usually a bedroom with a computer or television and a few board games, located next to the food which was always laid out buffet style. My favorite moments were when we would lip sync for our lives by doing drag karaoke, where my cousins and I would lock ourselves away and perform great popular music hits for an invisible audience. We pulled songs from Christina Aguilera or Britney Spears’ latest album to older joints that circulated long before our time, songs like “Stop! (In the Name of Love)” by Diana Ross and The Supremes and Patti LaBelle’s“Lady Marmalade.” But one song we kept in our catalog and that we seemed to have the most fun with was the Ike and Tina Turner cover of “Proud Mary.” Whenever we did “Mary” I insisted in being Tina. But what was it that drew me—a black gay boy rooted, like Tina, in Saint Louis, which is either the South or the Midwest depending on who -

Tina Turner What's Love Got to Do with It Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tina Turner What's Love Got To Do With It mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: What's Love Got To Do With It Country: Greece Released: 1993 Style: Pop Rock, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1864 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1287 mb WMA version RAR size: 1526 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 243 Other Formats: AUD MIDI MPC FLAC DXD AC3 MP2 Tracklist A1 I Don't Wanna Fight 6:06 A2 Rock Me Baby 3:57 A3 Disco Inferno 4:03 A4 Why Must We Wait Until Tonight? 5:53 A5 Stay Awhile 4:50 A6 Nutbush City Limits 3:19 A7 (Darlin') You Know I Love You 4:27 B1 Proud Mary 5:25 B2 A Fool In Love 2:54 B3 It's Gonna Work Out Fine 2:49 B4 Shake A Tail Feather 2:32 B5 I Might Have Been Queen 4:20 B6 What's Love Got To Do With It 3:49 B7 Tina's Wish 3:08 Notes made in Greece by Fabelsound Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year What's Love Got 0777 7 89486 2 Tina Parlophone, 0777 7 89486 2 UK & To Do With It 1993 9, CDPSD 126 Turner Parlophone 9, CDPSD 126 Europe (CD, Album) 0777 7 89486 2 What's Love Got Parlophone, 0777 7 89486 2 Tina 9, 7894862, To Do With It Parlophone, 9, 7894862, Italy 1993 Turner CDPCSD 128 (CD, Album) Parlophone CDPCSD 128 What's Love Got 0777 7 89486 4 Tina Parlophone, 0777 7 89486 4 UK & To Do With It 1993 3, TCPCSD 128 Turner Parlophone 3, TCPCSD 128 Europe (Cass, Album) What's Love Got 0777 7 89486 2 Tina 0777 7 89486 2 To Do With It Parlophone Australasia 1993 9 Turner 9 (CD, Album) What's Love Got 0777 Tina 0777 To Do With It Virgin US 1993 7-88189-4-6 Turner 7-88189-4-6 -

August Troubadour

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news January 2008 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 7, No. 4 what’s inside Welcome Mat ………3 Contributors Earl Thomas Remembers Ike Turner Full Circle.. …………4 Richard and Sandy Beesley Recordially, Lou Curtiss Front Porch... ………6 Jon Moore & the San Diego Concert Archive Dan Papaila Parlor Showcase …8 Jason Mraz Ramblin’... …………10 Bluegrass Corner Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze Stages Highway’s Song. …12 String Planet Of Note. ……………13 West of Memphis Sheila Sondergä rd String Planet Jenn Grinels The Hi-Lites ‘Round About ....... …14 January Music Calendar The Local Seen ……15 Photo Page JANUARY 2008 SAN DIEGO TROUBADOUR welcome mat Earl Thomas Remembers RSAN ODUIEGBO ADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Ike Turner (1931 - 2007) Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news he first time I ever hear the name Ike and bought the single, which featured their MISSION CONTRIBUTORS Turner was in 1970. My family was liv - version of “Come Together” on the B side. To promote, encourage, and provide an FOUNDERS ing on the island of Guam where my dad In 1971 my dad took me to see the movie Ike Turner alternative voice for the great local music that T r Ellen and Lyle Duplessie was station in the U.S. Navy. I was on a ban - Soul to Soul , which featured Ike and Tina, e is generally overlooked by the mass media; p Liz Abbott tam bowling league and would, every Wilson Pickett, the Staple Singers, and many p namely the genres of alternative country, o Kent Johnson H Saturday morning, go to the base’s bowling other top artists of that period. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/64 - Total : 2469 Vinyls Au 23/09/2021 Collection "Pop/Rock International" De Lolivejazz

Collection "Pop/Rock international" de lolivejazz Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 220 Volt Mind Over Muscle LP 26254 Pays-Bas 50 Cent Power Of The Dollar Maxi 33T 44 79479 Etats Unis Amerique A-ha The Singles 1984-2004 LP Inconnu Aardvark Aardvark LP SDN 17 Royaume-Uni Ac/dc T.n.t. LP APLPA. 016 Australie Ac/dc Rock Or Bust LP 88875 03484 1 EU Ac/dc Let There Be Rock LP ALT 50366 Allemagne Ac/dc If You Want Blood You've Got I...LP ATL 50532 Allemagne Ac/dc Highway To Hell LP ATL 50628 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP ATL 50257 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP 50257 France Ac/dc For Those About To Rock We Sal...LP ATL 50851 Allemagne Ac/dc Fly On The Wall LP 781 263-1 Allemagne Ac/dc Flick Of The Switch LP 78-0100-1 Allemagne Ac/dc Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap LP ATL 50 323 Allemagne Ac/dc Blow Up Your Video LP Inconnu Ac/dc Back In Black LP ALT 50735 Allemagne Accept Restless & Wild LP 810987-1 France Accept Metal Heart LP 825 393-1 France Accept Balls To The Walls LP 815 731-1 France Adam And The Ants Kings Of The Wild Frontier LP 84549 Pays-Bas Adam Ant Friend Or Foe LP 25040 Pays-Bas Adams Bryan Into The Fire LP 393907-1 Inconnu Adams Bryan Cuts Like A Knife LP 394 919-1 Allemagne Aerosmith Rocks LP 81379 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Live ! Bootleg 2LP 88325 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Get Your Wings LP S 80015 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Classics Live! LP 26901 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits LP 84704 Pays-Bas Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic F.. -

Tina & Daddy the Telephone Call / No Charge Mp3, Flac

Tina & Daddy The Telephone Call / No Charge mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Telephone Call / No Charge Country: US Released: 1974 Style: Country MP3 version RAR size: 1768 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1193 mb WMA version RAR size: 1775 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 799 Other Formats: ASF ADX MP1 AA WAV DTS AU Tracklist A –Tina & Daddy The Telephone Call B –Tina & Mommy No Charge Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Tina & Daddy / Tina & Mommy - Tina & Daddy / 5-11099 The Telephone Call / No Charge Epic 5-11099 US 1974 Tina & Mommy (7", Single, Mono, Promo, Whi) Tina & Daddy / Tina & Mommy - Tina & Daddy / 5-11099 The Telephone Call / No Charge Epic 5-11099 US 1974 Tina & Mommy (7", Single) The Telephone Call / No Charge 5-11099 Tina & Daddy Epic 5-11099 US 1974 (7") Tina & Daddy / Tina & Mommy - Tina & Daddy / 5-11099 The Telephone Call / No Charge Epic 5-11099 US 1974 Tina & Mommy (7", Mono, Promo) Tina & Daddy / Tina & Mommy - Tina & Daddy / S EPC 2313 The Telephone Call / No Charge Epic S EPC 2313 UK 1974 Tina & Mommy (7", Promo) Related Music albums to The Telephone Call / No Charge by Tina & Daddy Tina Turner - Live USA Feat., Tina Arena - Never Tina Turner - Tina Live - Private Dancer Tour Tina Turner - On Fire, The Best Of Tina Live Talky Tina - Talky Tina Ike & Tina Turner - The Gospel According To Ike And Tina Browning Bryant - One Time In A Million / Tina Tina Turner - The Tina Turner (Montage Mix) Tina Turner - Tina Turns The Country On Ike & Tina Turner - I'll Never Need More Than This Ana Kokić, Tina Ivanović - Untitled Tina Bednoff & The Cocktailers - Jump, Sister, Jump. -

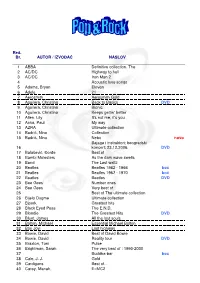

Red. Br. AUTOR / IZVOĐAČ NASLOV 1 ABBA Definitive Collection. the 2

Red. Br. AUTOR / IZVO ĐAČ NASLOV 1 ABBA Definitive collection. The 2 AC/DC Highway to hell 3 AC/DC Iron Man 2 4 Acoustic love songs 5 Adams, Bryan Eleven 6 Adele 21 7 Aerosmith Aerosmith Gold 8 Aguilera, Christina Back to Basics DVD 9 Aguilera, Christina Bionic 10 Aguilera, Christina Keeps gettin' better 11 Allen, Lily It's not me, it's you 12 Anka, Paul My way 13 AZRA Ultimate collection 14 Badri ć, Nina Collection 15 Badri ć, Nina Nebo novo Bajaga i instruktori; beogradski 16 koncert; 23.12.2006. DVD 17 Balaševi ć, Đor đe Best of 18 Bambi Molesters As the dark wave swells 19 Band The Last waltz 20 Beatles Beatles 1962 - 1966 box 21 Beatles Beatles 1967 - 1970 box 22 Beatles Beatles DVD 23 Bee Gees Number ones 24 Bee Gees Very best of 25 Best of The ultimate collection 26 Bijelo Dugme Ultimate collection 27 Bjoerk Greatest hits 28 Black Eyed Peas The E.N.D. 29 Blondie The Greatest Hits DVD 30 Blunt, James All the lost souls 31 Bolton, Michael Essential Michael Bolton 32 Bon Jovi Lost highway 33 Bowie, David Best of David Bowie 34 Bowie, David Reality tour DVD 35 Braxton, Toni Pulse 36 Brightman, Sarah The very best of : 1990-2000 37 Buddha-bar box 38 Cale, J. J. Gold 39 Cardigans Best of... 40 Carey, Mariah, E=MC2 41 Cetinski, Toni Ako to se zove ljubav 42 Cetinski, Toni Arena live 2008 DVD 43 Cetinski, Toni Triptonyc 44 Cetinski, Toni The Best of 2CD 45 Cher Gold 46 Cinquetti, Gigliola Chiamalo amore.. -

Wateraerobics Master by Song 2207 Songs, 5.9 Days, 16.35 GB

Page 1 of 64 wateraerobics master by song 2207 songs, 5.9 days, 16.35 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Act Of Contrition 2:19 Like A Prayer Madonna 2 The Actress Hasn't Learned The… 2:32 Evita [Disc 2] Madonna, Antonio Banderas, Jo… 3 Addicted To Love 5:23 Tina Live In Europe Tina Turner 4 Addicted To Love (Glee Cast Ve… 3:59 Glee: The Music, Tested Glee Cast 5 Adiós, Pampa Mía! 3:08 Tango Julio Iglesias 6 Advice For The Young At Heart 4:55 The Seeds Of Love Tears For Fears 7 Affairs Of The Heart 3:47 Black Moon Emerson, Lake & Palmer 8 After Midnight 3:09 Time Pieces - The Best Of Eric… Eric Clapton 9 Afternoon Delight (Glee Cast Ve… 3:12 Afternoon Delight (Glee Cast Ve… Glee Cast 10 Against All Odds (Take A Look A… 4:14 Cardiomix The Chris Phillips Project 11 Ain't It A Shame 3:37 The Complete Collection And Th… Barry Manilow 12 Ain't It Heavy 4:25 Greatest Hits: The Road Less Tr… Melissa Etheridge 13 Ain't Looking For Love 4:41 Big Ones Loverboy 14 Ain't Nothing Like The Real Thing 2:17 Every Great Motown Hit of Marvi… Marvin Gaye 15 Ain't That Peculiar 3:02 Every Great Motown Hit of Marvi… Marvin Gaye 16 Air (Andante Religioso) from Hol… 6:53 an Evening with Friends Edvard Grieg - Sir Neville Marrin… 17 Alabama Song 3:20 Best Of The Doors [Disc 1] The Doors 18 Alcazar 7:29 Upfront David Sanborn 19 Alena (Jazz) 5:30 Nightowl Gregg Karukas 20 Alive 3:59 Best Of The Bee Gees, Vol. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Glenn Medeiros

AUTHORISED AND ENDORSED BY THE AUSTRALIAN RECORD INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION 3 WEEKS ENDING 10th JANUARY 1988 TW LW TI TITLE/ARTIST Co. Cat. No. 1 1 9 NEVER GONNA GIVE YOU UP Rick Astley BMG/RCA 104746 • 2 5 5 GOT MY MIND SET ON YOU George Harrison WEA 728178 3 2 6 FAITH George Michael CBS 651119 7 4 3 10 RUN TO PARADISE Choirboys FES K 378 5 4 8 TOO MUCH AIN'T ENOUGH LOVE Jimmy Barnes FES K 424 6 6 12 HOLD ME NOW Johnny Logan CBS 650893 7 7 8 5 THE WAY YOU MAKE ME FEEL Michael Jackson CBS 651275 7 8 7 11 NEED YOU TONIGHT INXS WEA 7258181 9 9 17 LA BAMBA Los Lobos POL 886168-7 10 10 6 MONY MONY Billy Idol FES K 421 11 12 13 BAD Michael Jackson CBS 651100 7 12 15 4 MY OBSESSION Icehouse FES K 449 13 11 16 ELECTRIC BLUE Icehouse FES K 389 14 16 8 TO HER DOOR Paul Kelly &The Coloured Girls FES K 412 15 13 6 WE'LL BE TOGETHER Sting FES K 416 16 14 10 YOU WIN AGAIN Bee Gees WEA 728351 17 17 6 BRIDGE TO YOUR HEART Wax BMG/RCA 104723 • 18 23 8 IS THIS LOVE Whitesnake EMI EMI 1974 19 19 6 UNCHAIN MY HEART Joe Cocker CBS LS 1980 20 18 13 DO TO YOU The Machinations FES K 364 21 20 11 CAUSING A COMMOTION Madonna WEA 728224 22 22 7 BEETHOVEN (I LOVE TO LISTEN TO) Eurythmics BMG/RCA 104764 • 23 42 2 I THINK WE'RE ALONE NOW Tiffany WEA 753167 24 25 4 COME ON, LET'S GO Los Lobos POL 886196-7 25 24 5 HERE I GO AGAIN Whitesnake EMI EMI 2007 26 26 5 NOTHING'S GONNA CHANGE MY LOVE FOR YOU Glenn Medeiros POL 888 610-7 27 27 5 THE RIGHT STUFF Bryan Ferry VIR/EMI VS 940 28 31 3 CHERRY BOMB John Cougar Mellencamp POL 888 934-7 29 21 11 HAMMERHEAD James Reyne EMI CP1996 30 28 24 OLD TIME ROCK AND ROLL Bob Seger EMI CP1192 31 29 18 BEDS ARE BURNING Midnight Oil CBS 651015 7 • 32 NEW PUMP UP THE VOLUME M.A.R.R S VIR/EMI AD 707 33 32 12 LITTLE LIES Fleetwood Mac WEA 728291 34 34 22 LOCOMOTION Kylie Minogue FES K 319 35 30 7 ADULTERY Do Re Mi VIR/EMI VS 1005 36 33 4 BACK IN THE U.S.S.R. -

Tina Turner Tina Live - Private Dancer Tour Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tina Turner Tina Live - Private Dancer Tour mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Tina Live - Private Dancer Tour Country: UK Released: 1994 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1528 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1191 mb WMA version RAR size: 1464 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 249 Other Formats: TTA AIFF AHX MOD AC3 RA VOX Tracklist Hide Credits VHS V-1 Intro Show Some Respect V-2 Written-By – S. Shifrin*, T. Britten* I Might Have Been Queen (Soul Survivor) V-3 Written-By – West-Oram*, Ostoj*, Hine* What's Love Got To Do With It V-4 Written-By – G. Lyle*, T. Britten* I Can't Stand The Rain V-5 Written-By – Peebles*, Miller*, Bryant* Better Be Good To Me V-6 Written-By – Chinn-Chapman*, Knight* Private Dancer V-7 Written-By – Mark Knopfler Let's Stay Together V-8 Written-By – Green*, Jackson*, Mitchell* Help! V-9 Written-By – J. Lennon-P. McCartney* It's Only Love (Duet With Bryan Adams) V-10 Vocals – Bryan AdamsWritten-By – B. Adams*, J. Vallance* Tonight (Duet With David Bowie) V-11 Vocals – David BowieWritten-By – D. Bowie*, I. Pop* Let's Dance - Version I (Duet With David Bowie) V-12 Vocals – David BowieWritten By – T. SheridenWritten-By – J. Lee* Let's Dance - Version II (Duet With David Bowie) V-13 Vocals, Written-By – David Bowie CD CD-1 Intro CD-2 Show Some Respect CD-3 I Might Have Been Queen (Soul Survivor) CD-4 What's Love Got To Do With It CD-5 I Can't Stand The Rain CD-6 Better Be Good To Me CD-7 Private Dancer CD-8 Let's Stay Together CD-9 Help! CD-10 It's Only Love (Duet With Bryan Adams) CD-11 Tonight (Duet