Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 127 April 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Terre Ne Nous Appartient Pas, Ce Sont Nos Enfants Qui Nous La Prêtent”

Réserve Naturelle Nationale de Saint-Martin Le Journal “La terre ne nous appartient pas, ce sont nos enfants qui nous la prêtent” Trimestriel n°29 juillet 2017 Sommaire Megara 2017 : troisième édition: 4/5 Megara 2017: Mission #3 Un atelier en faveur des récifs et 6 A workshop In Support of Reefs des herbiers and Plant Beds Une thèse en faveur des herbiers 7 A Thesis About Plant Beds Un plan structuré contre la 8 A Solid Plan To Fight Hydrocarbon pollution aux hydrocarbures Pollution Des données conservées 9 Conserving Data Forever and Ever Des échasses clandestines 10 Clandestine Birds Nesting Sauvetage d’une tortue fléchée 11 Saving An Injured Turtle Un filet au Galion 12 Fishnet at Galion Saisie d’un filet de 300 mètres 12 300-meter Fishnet Seized Double saisie pour deux pêcheurs 13 Double Trouble For Two Fishermen Quads dans la Réserve 14 Quads in the Réserve: Poisson-lion et ciguatera 15 Lionfish and Ciguatera: Le centre équestre déménagera 16 Galion Equestrian Center To Move 17 bouées de mouillage à Tintamare 17 17 Buoys at Tintamare De nouveaux panneaux, interactifs 18 New Interactive Signage Bye bye Romain Renoux ! 19 Bye bye Romain Renoux! Toutes les réserves en Martinique 20/21 Nature Reserves Met In Martinique Cours de SVT à Pinel 22 Science Classes at Pinel Des régatiers et des baleines 23 Regattas VS Whales Un nouveau parc marin. Bravo Aruba ! 24/25 A New Marine Park. Bravo Aruba! Le Forum UE-PTOM à Aruba 26 UE-PTOM Forum in Aruba BEST : 2 beaux projets à Anguilla 27/30 BEST: 2 Winning Projects in Anguilla Réunion sur les baleines à bosse 31/32 Metting about Humpback Whales BEST : dernier appel à projets 32/33 BEST: Last Call For Projects 2 Edito à nos visiteurs des sites préservés, des plages propres, des eaux de baignade de qualité, ils ne viendront plus ! Le maintien de notre biodiversi- té et la préservation des différents écosystèmes marins et terrestres à Saint Martin sont une pri- orité. -

Threats to Sea Turtles Artificial Lighting

Threats to Sea Turtles Artificial Lighting Artificial lighting is a significant sea turtle conservation problem. Sea turtle hatchlings instinctively move towards the brightest light when they hatch – on a natural beach, this is the night sky over the ocean. The artificial lighting causes the hatchlings to become disoriented, and ultimately leads to their death. Below are two maps. The “Artificial Lighting” map is a satellite image of the lights that are visible at night in Florida from space. The “Florida County” map will be used for reference. You will also need your “Sea Turtle Nesting Data” from an earlier lesson. Directions: Using the data provided identify areas where artificial lighting has the greatest impact on sea turtle hatchlings. Artificial Lighting Map Lightly shaded areas (yellow) - Lights visible at night from space Compare the “Artificial Lighting” map with the blank county map below. Color in the counties which have the most visible night lights from space. County Map Compare this data with data you collected earlier of the nesting sites of Green, Leatherback and Loggerhead turtles. Green Nesting Map Leatherback Nesting Map Loggerhead Nesting Map Questions 1. Describe the relationship between the nesting data and the artificial lighting data. ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ -

Background on Sea Turtles

Background on Sea Turtles Five of the seven species of sea turtles call Virginia waters home between the months of April and November. All five species are listed on the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants and classified as either “Threatened” or “Endangered”. It is estimated that anywhere between five and ten thousand sea turtles enter the Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer months. Of these the most common visitor is the loggerhead followed by the Kemp’s ridley, leatherback and green. The least common of the five species is the hawksbill. The Loggerhead is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle often reaching weights of 1000 lbs. However, the ones typically sighted in Virginia’s waters range in size from 50 to 300 lbs. The diet of the loggerhead is extensive including jellies, sponges, bivalves, gastropods, squid and shrimp. While visiting the Bay waters the loggerhead dines almost exclusively on horseshoe crabs. Virginia is the northern most nesting grounds for the loggerhead. Because the temperature of the nest dictates the sex of the turtle it is often thought that the few nests found in Virginia are producing predominately male offspring. Once the male turtles enter the water they will never return to land in their lifetime. Loggerheads are listed as a “Threatened” species. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is the second most frequent visitor in Virginia waters. It is the smallest of the species off Virginia’s coast reaching a maximum weight of just over 100 lbs. The specimens sited in Virginia are often less than 30 lbs. -

Turtles, All Marine Turtles, Have Been Documented Within the State’S Borders

Turtle Only four species of turtles, all marine turtles, have been documented within the state’s borders. Terrestrial and freshwater aquatic species of turtles do not occur in Alaska. Marine turtles are occasional visitors to Alaska’s Gulf Coast waters and are considered a natural part of the state’s marine ecosystem. Between 1960 and 2007 there were 19 reports of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the world’s largest turtle. There have been 15 reports of Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). The other two are extremely rare, there have been three reports of Olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) and two reports of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Currently, all four species are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Prior to 1993, Alaska marine turtle sightings were mostly of live leatherback sea turtles; since then most observations have been of green sea turtle carcasses. At present, it is not possible to determine if this change is related to changes in oceanographic conditions, perhaps as the result of global warming, or to changes in the overall population size and distribution of these species. General description: Marine turtles are large, tropical/subtropical, thoroughly aquatic reptiles whose forelimbs or flippers are specially modified for swimming and are considerably larger than their hind limbs. Movements on land are awkward. Except for occasional basking by both sexes and egg-laying by females, turtles rarely come ashore. Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Although their age is often exaggerated, they probably live 50 to 100 years. Of the five recognized species of marine turtles, four (including the green sea turtle) belong to the family Cheloniidae. -

'Camouflage' Their Nests but Avoid Them and Create a Decoy Trail

Buried treasure—marine turtles do not ‘disguise’ or royalsocietypublishing.org/journal/rsos ‘camouflage’ their nests but avoid them and create a Research Cite this article: Burns TJ, Thomson RR, McLaren decoy trail RA, Rawlinson J, McMillan E, Davidson H, Kennedy — MW. 2020 Buried treasure marine turtles do not † ‘disguise’ or ‘camouflage’ their nests but avoid Thomas J. Burns , Rory R. Thomson, Rosemary them and create a decoy trail. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7: 200327. A. McLaren, Jack Rawlinson, Euan McMillan, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200327 Hannah Davidson and Malcolm W. Kennedy Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, and School of Life Sciences, Graham Kerr Building, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Received: 27 February 2020 University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Accepted: 6 April 2020 TJB, 0000-0003-0408-8014; MWK, 0000-0002-0970-5264 After laying their eggs and refilling the egg chamber, sea Subject Category: turtles scatter sand extensively around the nest site. This is presumed to camouflage the nest, or optimize local conditions Organismal and Evolutionary Biology for egg development, but a consensus on its function is Subject Areas: lacking. We quantified activity and mapped the movements of hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and leatherback (Dermochelys behaviour coriacea) turtles during sand-scattering. For leatherbacks, we also recorded activity at each sand-scattering position. Keywords: For hawksbills, we recorded breathing rates during nesting as hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, leatherback an indicator of metabolic investment and compared with turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, nesting behaviour published values for leatherbacks. Temporal and inferred metabolic investment in sand-scattering was substantial for both species. -

This Month, the Year of the Turtle Extends Its Hand to You, the Reader

Get involved in a citizen science program in your neighborhood, community, or around the world! Citizen science programs place people of all backgrounds and ages in partnerships with organizations and scientists to collect important biological data. There are many great programs focused on turtles available to the public. Below we highlight citizen science programs from North America and around the world with which you can become involved. We thank everyone who has contributed information on their citizen science programs to the Year of the Turtle thus far. We also greatly thank Dr. James Gibbs’ Herpetology course at SUNY-ESF, especially students Daren Card, Tim Dorr, Eric Stone, and Selena Jattan, for their contributions to our growing list of citizen science programs. Are you involved with a turtle citizen science program or have information on a specific project that you would like to share? Please send information on your citizen science programs to [email protected] and make sure your project helps us get more citizens involved in turtle science! Archelon, Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece This volunteer experience takes place on the islands of Zakynthos, Crete, and the peninsula of Peloponnesus, Greece. Volunteers work with the Management Agency of the National Marine Park of Zakynthos (NMPZ), the first National Marine Park for sea turtles in the Mediterranean. Their mission is to “implement protection measures for the preservation of the sea turtles.” Volunteers assist in protecting nests from predation and implementing a management plan for nesting areas. Volunteers also have the opportunity to assist in the treatment of rescued sea turtles that may have been caught in fishing gear or help with public awareness at the Sea Turtle Rescue Centre. -

The Latest Record of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys Coriacea

16 Coll. and Res. (2003) 16: 13-16 Coll. and Res. (2003) 16: 17-26 17 claw ending as knob; empodium divided, 5 rayed. without a short line on each side, admedian lines The Latest Record of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys with a semicircular line extending to lateral sides, Opisthosoma : dorsum with median ridge shorter and the 5-rayed empodium. coriacea) from Eastern Taiwan than submedian ridges, dorsally with about 51 rings, ventrally with about 53 microtuberculate Chun-Hsiang Chang1,2*, Chern-Mei Jang3, and Yen-Nien Cheng2 REFERENCES rings; 1st 3 dorsal annuli 9 long; lateral setae (c2) 10 long, Lt-Lt 44 apart, Lt\Vt1 38, Lt-Vt1 25; 1st 1Department of Biology, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK Keifer, H.H. 1977. Eriophyid studies C-13. ARS- ventral setae (d) 17 long, Vt1-Vt1 19 apart, 2Department of Geology, National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan 404 R.O.C. USDA, Washington, DC. 24pp. Vt1\Vt2 28, Vt1-Vt2 25; 2nd ventral setae (e) 17 3 Keifer, H.H. 1978. Eriophyid studies C-15. ARS- Department of Collection Management, National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung Taiwan 404 long, Vt2-Vt2 10 apart, Vt2\Vt3 40, Vt2-Vt3 38; USDA, Washington, DC. 24pp. R.O.C. 3rd ventral setae (f) 14 long, Vt3-Vt3 16 apart; Huang, K.W. 1999. The species and geographic accessory setae (h1) present. variation of eriophyoid mites on Yushania Coverflap: 19 wide, 12 long, with about 9 niitakayamensis of Taiwan. Proc. Symp. In (Received June 30, 2003; Accepted September 16, 2003) longitudinal ridges, genital setae (3a) 6 long, Gt- Insect Systematics and Evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

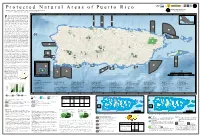

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Download Book (PDF)

HANDBOOK INDIAN TESTUDINES HANDBOOK INDIAN TESTUDINES B. K. TIKADER Zoological Survey of India, Calcutta R. C. SHARMA Desert Regional Station, Zoological Survey of India, Jodhpur Edited by the Director ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA, CALCUTTA © Government of India, 1985 Published: November, 1985 Price: Indian Rs. 150/00 Foreign : £ 20/00 $ 30/00 Printed at The Radiant Process Private Limited, Calcutta, India and Published by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Calcutta FOREWORD One of the objectives of Zoological Survey of India is to provide comprehensive systematic accounts on various groups of the Indian fauna. To achieve this objective, the Zoological Survey of India undertakes faunistic survey programmes and publishes the results in the form of research papers and reports and under the series "Fauna of India", "The Handbooks" and "Technical Monographs" The present contribution on the Turtles and Tortoises is the sixth in the series of "Handbooks" This is a very primitive group of animals which have a role in the conservation of Nature and are an important protein source. While studies on this group of animals began at the turn of this century, intensive studies were taken up only recently. The present "Handbook" gives a comprehensive taxonomic account of all the marine, freshwater and land turtles and tortoises of India, along with their phylogeny, distribution and keys for easy identification. It includes other information, wherever known, about their biology, ecology, conservation and captive breeding. A total of 32 species and subspecies distributed over sixteen genera and five families are dealt with here. I congratulate the authors for undertaking this work which I am sure will prove useful to students and researchers in the field of Herpetology both in India and abroad. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

Turtle Tracks Miami-Dade County Marine Extension Service

Turtle Tracks Miami-Dade County Marine Extension Service Florida Sea Grant Program DISTURBING A SEA TURTLE NEST IS A VIOLATION 4 OF STATE AND FEDERAL LAWS. 2 TURTLE TRACKS What To Do If You See A Turtle 1 3 SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION IN MIAMI-DADE COUNTY If you observe an adult sea turtle or hatchling sea turtles on the beach, please adhere to the following rules and guidelines: 1. It is normal for sea turtles to be crawling on the beach on summer nights. DO NOT report normal crawling or nesting (digging or laying eggs) to the Florida Marine Patrol unless the turtle is in a dangerous situation or has wandered off the beach. 1. Leatherback (on a road, in parking lot, etc.) 2. Stay away from crawling or nesting sea turtles. Although the 2. Kemp’s Ridley urge to observe closely will be great, please resist. Nesting is a 3. Green critical stage in the sea turtle’s life cycle. Please leave them 4. Loggerhead undisturbed. U.S. GOVERNMENTPRINTINGOFFICE: 1999-557-736 3. DO REPORT all stranded (dead or injured) turtles to the This information is a cooperative effort on behalf of the following organizations to Florida Marine Patrol. help residents of Miami-Dade County learn about sea turtle conservation efforts in 4. NEVER handle hatchling sea turtles. If you observe hatchlings this coastal region of the state. wandering away from the ocean or on the beach, call: NATIONAL Florida Marine Pat r ol 1-800- DIAL-FMP (3425-367) SAVE THE SEATURTLE FOUNDATION MIAMI-DADE COUNTY SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION PROGRAM 4419 West Tradewinds Avenue "To Protect Endangered or Threatened Marine Turtles for Fort Lauderdale, Floirda 33308 Future Generations" Phone: 954-351-9333 efore 1980, there was no documented sea Fax: 954-351-5530 Toll Free: 877-Turtle3 turtle activity in Mia m i - D ade County, due B mainly to the lack of an adequate beach-nesting Information has been drawn from “Sea Turtle Conservation Program“, a publication of the Broward County Department of Planning and Environmental Protection, habitat.