A Matter of Life and Death: Spectres of Spectatorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Types in Shakespeare August Goll

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 30 Article 4 Issue 1 May-June Summer 1939 Criminal Types in Shakespeare August Goll Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation August Goll, Criminal Types in Shakespeare, 30 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 22 (1939-1940) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CRIMINAL TYPES IN SHAKESPEARE JUDGE AUGUST GOLL Translated from the Danish by Julius Moritzen, 4003 Foster Ave., Brooklyn, N. Y. This is the third and concluding portion of Mr. Moritzen's translation. The first portion was published in No. 4 of this volume, November-December, 1938; the second in No. 5, January-February, 1939.-[Ed.] RICHARD III Herbert Spencer in his book on righteousness and justice de- clares their aim to be that state of society where each member, without relinquishing his individual liberty of action, nevertheless tolerates the bonds that the rights of others demand of him. In other words, the principle of mutual respect for the rights of others underlies the social formula to which he subscribes. The criminal denies by his acts this ideal. But none of the criminals so far discussed are directly opposed to the fundamentals of this ideal state when judged by their actions. -

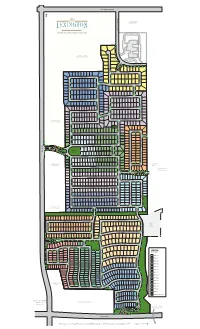

Lexington Phases Mastermap RH HR 3-24-17

ELDORADO PARKWAY MAMMOTH CAVE LANE CAVE MAMMOTH *ZONED FUTURE LIGHT RETAIL MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY MAJESTIC PRINCE CIRCLE MAMMOTH CAVE LANE T IN O P L I A R E N O D ORB DRIVE ARISTIDES DRIVE MACBETH AVENUE MANUEL STREETMANUEL SPOKANE WAY DARK STAR LANE STAR DARK GIACOMO LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDSTONE MANOR GRINDSTONE FUNNY CIDE COURT FUNNY THUNDER GULCH WAY BROKERS TIP LANE MANUEL STREETMANUEL E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND TRAIL LEONATUS LANE LEONATUS PONDER LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTERGREEN DRIVE COIT ROAD COIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD COUNT TURF COUNT DRIVE AMENITY SMARTY JONES STREET CENTER STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD 2 DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY 5 CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 1 Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE FLYING EBONY STREET LIGHT RETAIL Park AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE CONQUISTADOR COURT CONQUISTADOR LUCKY DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY OXBOW AVENUE OXBOW CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 4 WHIRLAWAY DRIVE 9 IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER ROAD C WAR EMBLEM PLACE WAR A N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R I V E 14DUST COMMANDER COURT CIRCLE PASS FORWARD DETERMINE DRIVE SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUIET RD. TIM TAM CIRCLE EASY GOER AVENUE LEGEND PILLORY DRIVE PILLORY BY PHASES HALMA HALMA TRAIL 11 PHASE 1 A PROUD CLAIRON STREET M E MIDDLEGROUND PLACE -

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

News Release ______

News Release _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Darren Rogers Senior Director, Communications & Media Services Churchill Downs Racetrack (502) 636-4461 (office) (502) 345-1030 (mobile) [email protected] SIR TRUEBADOUR GIVES ASMUSSEN HIS RECORD-EQUALING FIFTH BASHFORD MANOR LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Saturday, June 30, 2018) – Whispering Oaks Farm LLC ’s Sir Truebadour led every step of the way in Saturday’s 117th running of the $100,000 Bashford Manor (Grade III) on closing day at Churchill Downs’ 38-day Spring Meet to beat Mr Chocolate Chip by two lengths and give Hall of Fame trainer Steve Asmussen an impressive fifth win in the nation’s first graded stakes race for 2-year-olds. Ridden by Ricardo Santana Jr., Sir Truebadour, who was sent to post as the hot 3-2 favorite, ran six furlongs over a fast main track in 1:12.77 – the slowest of 19 Bashford Manor renewals at the six-furlong distance. Sir Truebadour was leg weary late in the stretch but had a jump on his 11 rivals after breaking alertly from post 4. He battled from the inside with 48-1 longshot The Song of John and Mr. Granite for the early lead and ran the first quarter mile in a swift :21.35. The Song of John got within a half-length of Sir Truebadour at the top of the stretch but the winner spurted clear after a half mile in :45.63 and drew clear midway down the lane, and had enough to hold on comfortably. “Steve and his team did a great job with this horse,” Santana said. -

Lex Mastermap Handout

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D . -

RICHARD III by William Shakespeare Directed by Ian Gallanar February 10 – March 5, 2017 Thank You High Sparks of Honor in Thee Have I Seen

RICHARD III By William Shakespeare Directed by Ian Gallanar February 10 – March 5, 2017 Thank You High sparks of honor in thee have I seen. - Richard II Sponsors Funders Mayor Catherine E. Pugh & the City of Baltimore This production has been funded by Mayor Catherine E. Pugh and the Baltimore Office of Promotion and The Arts The William G. Baker, Jr. Memorial Fund creator of the Baker Artist Awards | www.bakerartistawards.org Media Partners 2 RICHARD III Richard’s Revival A Note from the Founding Artistic Director Richard III is a remarkable play. The history in it is not very good. Shakespeare compresses events at will. The idea of who the protagonist and antago- Ian Gallanar. Photo by Theatre nists are in this play might not match the historical record. Consultants Collaborative Inc. The play is not as deeply moving or profound as King Lear or Hamlet. Instead, what makes this play great are Shakespeare’s craftsmanship and innovation. Richard, Duke of Gloucester is one of the greatest anti-heroes in the theater. Shakespeare prac- tically invents for the stage the notion that our main fi gure can be villainous and yet, somehow, likable. Why? Because he’s entertaining, he’s funny, he’s wicked, and he speaks to us directly. The anti-hero is a creation that has stood the test of time. My favorite period of Shake- speare in performance is the era in which troupes of actors toured the California gold rush towns. Their productions were deeply important to these guys in the middle of nowhere trying to strike it rich. -

The Tragedy of King Richard III by William Shakespeare

1 Shakespeare – live The Tragedy of King Richard III by William Shakespeare Historical background The real-life Richard III was born in1485. He was Edward IV’s brother and Richard, Duke of York’s third son. Upon Edward’s death in 1483 he imprisoned his nephews in the Tower of London, announced that they had died there and proclaimed himself King of England. In 1485 Richard III was killed during the Battle of Bosworth Field, at the hand of Henry Tudor (Earl of 5 Richmond) who was later to become Henry VII. In the period after his death Richard was often portrayed negatively, attacked or defamed in literary and historical accounts, particularly Thomas More’s ‘History of Richard III’, which was also a source for Shakespeare’s play. Later historians have attempted to clear his name to some degree, notably Horace Walpole in his 10 ‘Historic Doubts on the Life and Death of Richard III’. However, Richard III remains one of the most controversial figures in English history. The play The Tragedy of King Richard III is considered a historical tragedy. After Hamlet, it is Shakespeare’s second longest drama and yet it is one of his most often performed plays. There are at least half a dozen film versions of the play, in which some of the stage’s best actors have played major roles. 15 The drama unfolds in five acts, beginning with the exposition and the complication of the plot within the first two acts. Typically, the climax comes at the end of Act III. The dénouement and the finale follow in the remaining two acts. -

Alibhai-GB (By Hyperion-GB, 1938) – Determine (1954) Alydar (By

SIRES Pioneerof the Nile (by Empire Maker, 2006) – American Pharoah (2015) Polish Navy (by Danzig, 1984) – Sea Hero (1993) +Ponder (by Pensive, 1946) – Needles (1956) Alibhai-GB (by Hyperion-GB, 1938) – Determine (1954) Pretendre-GB (by Doutelle-GB, 1963) – Canonero II (1971) Alydar (by Raise a Native, 1975) – Alysheba (1987) & Strike the Gold (1991) Quiet American (by Fappiano, 1986) – Real Quiet (1998) At the Threshold (by Norcliffe-CAN, 1981) – Lil E. Tee (1992) Raise a Native (by Native Dancer, 1961) – Majestic Prince (1969) Australian-GB (by West Australian-GB, 1858) – Baden-Baden (1877) Reform (by Leamington-GB, 1871) – Azra (1892) Birdstone (by Grindstone, 2001) – Mine That Bird (2009) +Reigh Count (by Sunreigh-GB, 1925) – Count Fleet (1943) Black Toney (by Peter Pan, 1911) – Black Gold (1924) & Brokers Tip (1933) Royal Coinage (by Eight Thirty, 1952) – Venetian Way (1960) Blenheim II-GB (by Blandford-IRE, 1927) – Whirlaway (1941) & Jet Pilot (1947) Royal Gem II-AUS (by Dhoti-GB, 1942) – Dark Star (1953) Bob Miles (by Pat Malloy, 1881) – Manuel (1899) @Runnymede (by Voter-GB, 1908) – Morvich (1922) Bodemeister (by Empire Maker, 2009) – Always Dreaming (2017) Saggy (by Swing and Sway, 1945) – Carry Back (1961) Bold Bidder (by Bold Ruler, 1962) – Cannonade (1974) & Spectacular Bid (1979) Scat Daddy (by Johannesburg, 2004) – Justify (2018) Bold Commander (by Bold Ruler, 1960) – Dust Commander (1970) Sea King-GB (by Persimmon-GB, 1905) – Paul Jones (1920) Bold Reasoning (by Boldnesian, 1968) – Seattle Slew (1977) +Seattle Slew (by Bold Reasoning, 1974) – Swale (1984) Bold Ruler (by Nasrullah-GB, 1954) – Seattle Slew (1973) Silver Buck (by Buckpasser, 1978) – Silver Charm (1997) +Bold Venture (by St. -

Wild Night Tapit Filly Tops Sale at $1.15 Million Fasig-Tipton/Photos by Z Fasig-Tipton/Photos SELENITE, MARK MY WAY WIN N.Y

Tuesday, August 5, 2014 Year 14 • No. 15 T he aratoga Saratoga’s Daily Newspaper on Thoroughbred Racing Wild Night Tapit filly tops sale at $1.15 million Fasig-Tipton/Photos by Z Fasig-Tipton/Photos SELENITE, MARK MY WAY WIN N.Y. STALLION STAKES • FULL SALES RESULTS FROM FIRST NIGHT Belmont Derby Inv. S.-G1 winner Diana S.-G1 winner MR SPEAKER SOMALI LEMONADE Donn H.-G1 winner LEA Man o’ War S-G1 winner IMAGINING 14 Graded SWs This Year were Foaled/Raised at Claiborne, including Grade 1 SWs IMAGINING • LEA • MR SPEAKER • SOMALI LEMONADE • LIDERIS ___________________________________ Watch for 2014 Keeneland September Yearlings • By Such Sires as • WAR FRONT, FLATTER, BLAME, ARCH, PULPIT, HORSE GREELEY, TRAPPE SHOT, STROLL, PROUD CITIZEN, MORE THAN READY, SPEIGHTSTOWN, AFLEET ALEX, CURLIN, QUALITY ROAD, CAPE BLANCO (IRE), LANGFUHR, CITY ZIP, ESKENDEREYA, GHOSTZAPPER Post Office Box 150 Paris, Kentucky 40362-0150 Tel.(859) 233-4252 Fax 987-0008 claibornefarm.com INQUIRIES TO BERNIE SAMS e-mail: [email protected] © ADAM COGLIANESE, PATRICIA MCQUEEN, ADAM MOOSHIAN 2 14-0555.CLB.CLBRaised.SarSp.Aug5.indd 1 The Saratoga Special Tuesday, August8/4/14 5, 3:19 2014 PM here&there... at Saratoga NAME OF THE DAY Miss Metropolitan, Hip 98. The chestnut filly is a half-sister to millionaire True Metropolitan and sells tonight at Fasig-Tipton. NAMES OF THE DAY SUGGESTIONS Hip 87 is a colt by Harlan’s Holiday out of Soloing. How about Guy’s Weekend? Hip 117 is a colt by Street Sense out of Useewhatimsaying. We’d go with Fagedaboudit or maybe Badabing. -

SOLILOQUIES and the EVOLUTION of CHARACTER in RICHARD III and HAMLET by AMANDA JEANNETTE SEELY a Thesis Submitted to the Honors

Soliloquies and the Evolution of Character in Richard III and Hamlet Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Seely, Amanda Jeannette Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 21:03:20 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/244795 SOLILOQUIES AND THE EVOLUTION OF CHARACTER IN RICHARD III AND HAMLET By AMANDA JEANNETTE SEELY A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelor's Degree With Honors in English THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY 2012 Peter Medine Department of English STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Signed (J.ffut The University of Arizona Electronic Theses and Dissertations Reproduction and Distribution Rights Form Name (Last, First, Middle) Degree title (eg BA, BS, BSE, BSB, BFA): Honors area (eg Molecular and Cellular Biology, English, Studio Art): Date thesis submitted to Honors College: Title of Honors thesis: :The University of I hereby grant to the University of Arizona Library the nonexclusive Arizona Library Release worldwide right to reproduce and distribute my dissertation or thesis and abstract (herein, the "licensed materials"), in whole or in part, in any and all media of distribution and in any format in existence now or developed in the future. -

The Hollow Crown: the Wars of the Roses

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 3 MAY 2016 The Hollow Crown: The Wars of the Roses Henry VI Part I, Henry VI Part II and Richard III Following 2012's critically acclaimed BAFTA winning first series, The Hollow Crown: The Wars of the Roses is the concluding part of an ambitious and thrilling cycle of Shakespeare's Histories filmed for BBC Two, comprising Henry VI Part I & II, and Richard III, and featuring the very best of British on-screen talent. A Neal Street Co-Production with Carnival / NBC Universal and Thirteen for BBC STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 3 MAY 2016 Synopses Henry VI Part I Henry V is dead, and against the backdrop of Wars in France the English nobles are beginning to quarrel. News of defeat at Orleans reaches the Duke of Gloucester, the Lord Protector, and other nobles in England. Henry VI, still an infant, is proclaimed King. Seventeen years later the rivalries at Court have intensified; Gloucester and the Bishop of Winchester argue openly in front of the King. Rouen falls to the French but Plantagenet, recently restored as the Duke of York, Exeter and Talbot pledge to recapture the city from the Dauphin. Battle commences and the French, led by Joan of Arc, defeat the English. Valiant Talbot and his son John are killed. Warwick and Somerset arrive after the battle to join forces with the survivors and retake Rouen. Somerset woos Margaret of Anjou as a potential bride for Henry VI. Plantagenet takes Joan of Arc prisoner and she is burnt at the stake. Gloucester protests but still Margaret is introduced as Henry's queen. -

The Battle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Summer 2015 The aB ttle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare Erin K. Miller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Erin K., "The aB ttle of Good nda Evil in Shakespeare" (2015). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 70. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/70 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Battle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Erin Miller July 2015 Mentor: Dr. Patricia Lancaster Reader: Dr. Jennifer Cavenaugh Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Introduction Drama through the ages—from the Greeks’ Oedipus Rex to the morality plays of the Middle Ages —centers on an exploration of the human condition. In antiquity, religious celebrations to honor the gods and appeal for their favor gradually give birth to Greek theater, and these early plays, most of which are tragedies, focus on man’s suffering. What starts as the impact of fate on the life of man becomes, by the Middle Ages, a religious spectacle centered on evil’s impact on man. The Church of the Middle Ages frames the battle as a conflict of vice and virtue through stories in the life of Christ.