Primates in Peril: the World's 25 Most Endangered Primates 2018–2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

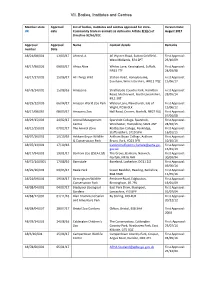

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Lemur News 7 (2002).Pdf

Lemur News Vol. 7, 2002 Page 1 Conservation International’s President EDITORIAL Awarded Brazil’s Highest Honor In recognition of his years of conservation work in Brazil, CI President Russell Mittermeier was awarded the National Are you in favor of conservation? Do you know how conser- Order of the Southern Cross by the Brazilian government. vation is viewed by the academic world? I raise these ques- Dr. Mittermeier received the award on August 29, 2001 at tions because they are central to current issues facing pri- the Brazilian Ambassador's residence in Washington, DC. matology in general and prosimians specifically. The National Order of the Southern Cross was created in The Duke University Primate Center is in danger of being 1922 to recognize the merits of individuals who have helped closed because it is associated with conservation. An inter- to strengthen Brazil's relations with the international com- nal university review in 2001 stated that the Center was too munity. The award is the highest given to a foreign national focused on conservation and not enough on research. The re- for service in Brazil. viewers were all researchers from the "hard" sciences, but For the past three decades, Mittermeier has been a leader in they perceived conservation to be a negative. The Duke ad- promoting biodiversity conservation in Brazil and has con- ministration had similar views and wanted more emphasis ducted numerous studies on primates and other fauna in the on research and less on conservation. The new Director has country. During his time with the World Wildlife Fund three years to make that happen. -

Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea

Primate Conservation 2009 (24): 99–105 Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea Thomas M. Butynski¹,², Yvonne A. de Jong² and Gail W. Hearn¹ ¹Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA ²Eastern Africa Primate Diversity and Conservation Program, Nanyuki, Kenya Abstract: Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea, has a rich (eight genera, 11 species), unique (seven endemic subspecies), and threat- ened (five species) primate fauna, but the taxonomic status of most forms is not clear. This uncertainty is a serious problem for the setting of priorities for the conservation of Bioko’s (and the region’s) primates. Some of the questions related to the taxonomic status of Bioko’s primates can be resolved through the statistical comparison of data on their body measurements with those of their counterparts on the African mainland. Data for such comparisons are, however, lacking. This note presents the first large set of body measurement data for each of the seven species of monkeys endemic to Bioko; means, ranges, standard deviations and sample sizes for seven body measurements. These 49 data sets derive from 544 fresh adult specimens (235 adult males and 309 adult females) collected by shotgun hunters for sale in the bushmeat market in Malabo. Key Words: Bioko Island, body measurements, conservation, monkeys, morphology, taxonomy Introduction gordonorum), and surprisingly few such data exist even for some of the more widespread species (for example, Allen’s Comparing external body measurements for adult indi- swamp monkey Allenopithecus nigroviridis, northern tala- viduals from different sites has long been used as a tool for poin monkey Miopithecus ogouensis, and grivet Chlorocebus describing populations, subspecies, and species of animals aethiops). -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Low Paternity Skew and the Influence of Maternal Kin in an Egalitarian

Low paternity skew and the influence of maternal kin in an egalitarian, patrilocal primate Karen B. Striera,1, Paulo B. Chavesb, Sérgio L. Mendesc, Valéria Fagundesc, and Anthony Di Fioreb,d aDepartment of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706; bDepartment of Anthropology and Center for the Study of Human Origins, New York University, New York, NY 10003; cDepartamento de Ciências Biológicas, Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Maruipe, Vitória, ES 29043-900, Brazil; and dDepartment of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712 Contributed by Karen B. Strier, October 12, 2011 (sent for review September 11, 2011) Levels of reproductive skew vary in wild primates living in The fecal samples used for paternity analyses included the 22 multimale groups depending on the degree to which high-ranking infants born between 2005 and 2007 that survived to ≥2.08 y of males monopolize access to females. Still, the factors affecting age, their 21 mothers (representing diverse ages and histories) paternity in egalitarian societies remain unexplored. We combine (Table S1), and the 24 adult males that were possible sires of at unique behavioral, life history, and genetic data to evaluate the least one infant (Table S2). We considered a male to be a po- distribution of paternity in the northern muriqui (Brachyteles tential sire for an infant if he was >5 y and was known to have hypoxanthus), a species known for its affiliative, nonhierarchical completed a copulation before the infant’s estimated conception relationships. We genotyped 67 individuals (22 infants born over a date (birth date minus mean 216.4-d gestation) (16). -

Enrichment for Nonhuman Primates, 2005

A six-booklet series on providing appropriate enrichment for baboons, capuchins, chimpanzees, macaques, marmosets and tamarins, and squirrel monkeys. Contents ...... Introduction Page 4 Baboons Page 6 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues References Common Names of the Baboon Capuchins Page 17 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues Resources Common Names of Capuchins Chimpanzees Page 28 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues Resources Common Names of Chimpanzees contents continued on next page ... Contents Contents continued… ...... Macaques Page 43 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues Resources Common Names of the Macaques Sample Pair Housing SOP -- Macaques Marmosets and Tamarins Page 58 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Safety Issues References Common Names of the Callitrichids Squirrel Monkeys Page 73 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues References Common Names of Squirrel Monkeys ..................................................................................................................... For more information, contact OLAW at NIH, tel (301) 496-7163, e-mail [email protected]. NIH Publication Numbers: 05-5745 Baboons 05-5746 Capuchins 05-5748 Chimpanzees 05-5744 Macaques 05-5747 Marmosets and Tamarins 05-5749 Squirrel Monkeys Contents Introduction ...... Nonhuman primates maintained in captivity have a valuable role in education and research. They are also occasionally used in entertainment. The scope of these activities can range from large, accredited zoos to small “roadside” exhib- its; from national primate research centers to small academic institutions with only a few monkeys; and from movie sets to street performers. Attached to these uses of primates comes an ethical responsibility to provide the animals with an environment that promotes their physical and behavioral health and well-be- ing. -

Diets of Howler Monkeys

Chapter 2 Diets of Howler Monkeys Pedro Américo D. Dias and Ariadna Rangel-Negrín Abstract Based on a bibliographical review, we examined the diets of howler mon- keys to compile a comprehensive overview of their food resources and document dietary diversity. Additionally, we analyzed the effects of rainfall, group size, and forest size on dietary variation. Howlers eat nearly all available plant parts in their habitats. Time dedicated to the consumption of different food types varies among species and populations, such that feeding behavior can range from high folivory to high frugivory. Overall, howlers were found to use at least 1,165 plant species, belonging to 479 genera and 111 families as food sources. Similarity in the use of plant taxa as food sources (assessed with the Jaccard index) is higher within than between howler species, although variation in similarity is higher within species. Rainfall patterns, group size, and forest size affect several dimensions of the dietary habits of howlers, such that, for instance, the degree of frugivory increases with increased rainfall and habitat size, but decreases with increasing group size in groups that live in more productive habitats. Moreover, the range of variation in dietary habits correlates positively with variation in rainfall, suggesting that some howler species are habitat generalists and have more variable diets, whereas others are habi- tat specialists and tend to concentrate their diets on certain plant parts. Our results highlight the high degree of dietary fl exibility demonstrated by the genus Alouatta and provide new insights for future research on howler foraging strategies. Resumen Con base en una revisión bibliográfi ca, examinamos las dietas de los monos aulladores para describir exhaustivamente sus recursos alimenticios y la diversidad de su dieta. -

Extreme Ecological Specialization in a Rainforest Mammal, the Bornean

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.03.233999; this version posted August 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 2 3 4 Extreme ecological specialization in a rainforest mammal, 5 the Bornean tufted ground squirrel, Rheithrosciurus macrotis 6 7 8 Andrew J. Marshall1*, Erik Meijaard2, and Mark Leighton3 9 10 1Department of Anthropology, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Program in the 11 Environment, and School for Environment and Sustainability, 101 West Hall, 1085 S. University 12 Ave, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 48109 USA. 13 2Borneo Futures, Block C, Unit C8, Second Floor, Lot 51461, Kg Kota Batu, Mukim Kota Batu, 14 BA 2711, Brunei Darussalam. 15 3Harvard University, 11 Divinity Ave, Cambridge, MA, 02138, U.S.A. 16 17 * Corresponding author 18 E-mail: [email protected] (AJM) 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.03.233999; this version posted August 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 19 Abstract 20 The endemic Bornean tufted ground squirrel, Rheithrosciurus macrotis, has attracted great 21 interest among biologists and the public recently. Nevertheless, we lack information on the most 22 basic aspects of its biology. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 09:14:05PM Via Free Access 218 Rode-Margono & Nekaris – Impact of Climate and Moonlight on Javan Slow Lorises

Contributions to Zoology, 83 (4) 217-225 (2014) Impact of climate and moonlight on a venomous mammal, the Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus Geoffroy, 1812) Eva Johanna Rode-Margono1, K. Anne-Isola Nekaris1, 2 1 Oxford Brookes University, Gipsy Lane, Headington, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK 2 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: activity, environmental factors, humidity, lunarphobia, moon, predation, temperature Abstract Introduction Predation pressure, food availability, and activity may be af- To secure maintenance, survival and reproduction, fected by level of moonlight and climatic conditions. While many animals adapt their behaviour to various factors, such nocturnal mammals reduce activity at high lunar illumination to avoid predators (lunarphobia), most visually-oriented nocturnal as climate, availability of resources, competition, preda- primates and birds increase activity in bright nights (lunarphilia) tion, luminosity, habitat fragmentation, and anthropo- to improve foraging efficiency. Similarly, weather conditions may genic disturbance (Kappeler and Erkert, 2003; Beier influence activity level and foraging ability. We examined the 2006; Donati and Borgognini-Tarli, 2006). According response of Javan slow lorises (Nycticebus javanicus Geoffroy, to optimal foraging theory, animal behaviour can be seen 1812) to moonlight and temperature. We radio-tracked 12 animals as a trade-off between the risk of being preyed upon in West Java, Indonesia, over 1.5 years, resulting in over 600 hours direct observations. We collected behavioural and environmen- and the fitness gained from foraging (Charnov, 1976). tal data including lunar illumination, number of human observ- Perceived predation risk assessed through indirect cues ers, and climatic factors, and 185 camera trap nights on potential that correlate with the probability of encountering a predators. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

WIAD CONSERVATION a Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity

WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 2 Ohu Map ...................................................................................................................................... 3 History of WIAD Conservation ...................................................................................................... 4 WIAD Legends .............................................................................................................................. 7 The Story of Julug and Tabalib ............................................................................................................... 7 Mou the Snake of A’at ........................................................................................................................... 8 The Place of Thunder ........................................................................................................................... 10 The Stone Mirror ................................................................................................................................. 11 The Weather Bird ................................................................................................................................ 12 The Story of Jelamanu Waterfall .........................................................................................................