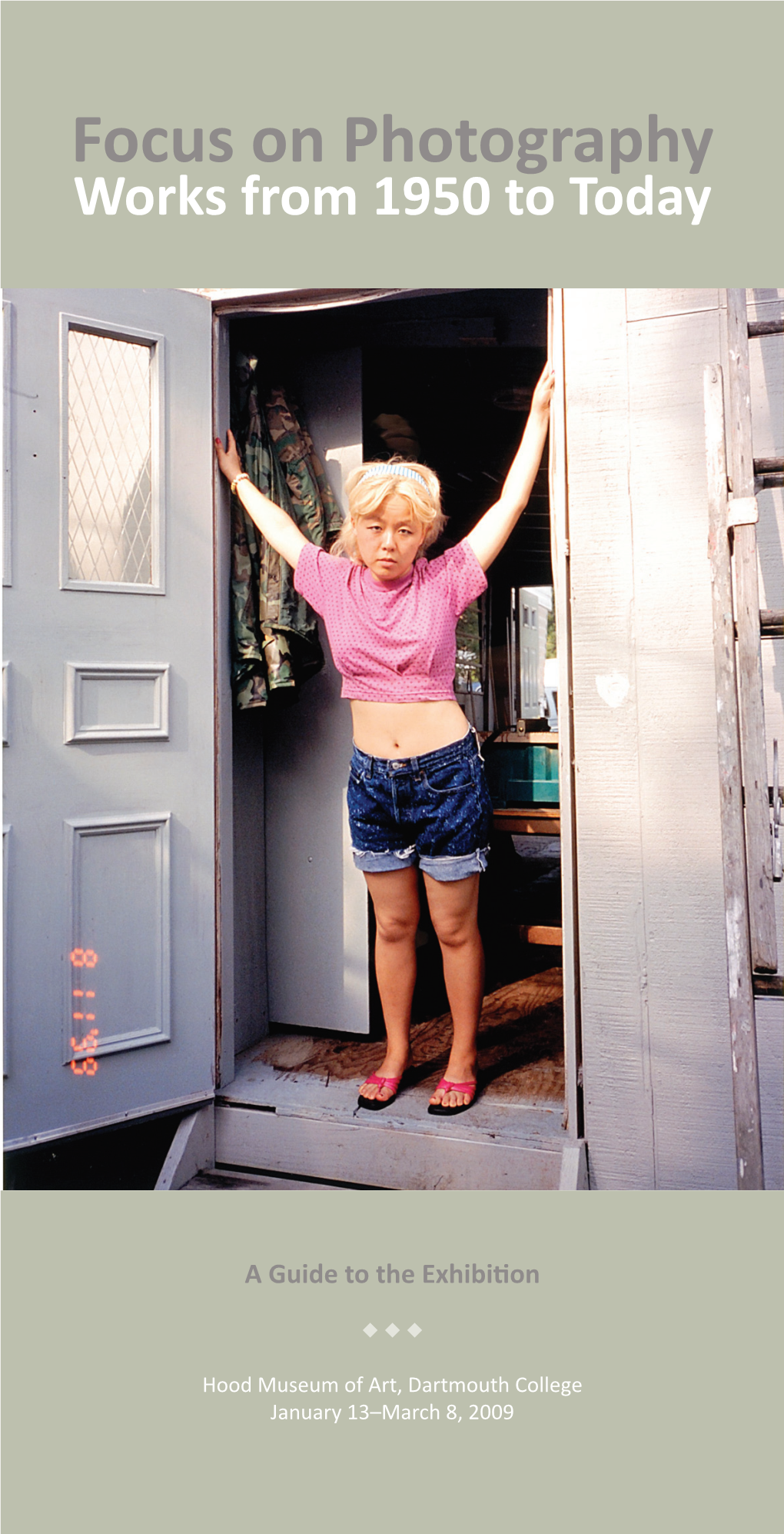

Focus on Photography Works from 1950 to Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL UPDATE Winter 2019

ANNUAL UPDATE winter 2019 970.925.3721 | aspenhistory.org @historyaspen OUR COLLECTIVE ROOTS ZUPANCIS HOMESTEAD AT HOLDEN/MAROLT MINING & RANCHING MUSEUM At the 2018 annual Holden/Marolt Hoedown, Archive Building, which garnered two prestigious honors in 2018 for Aspen’s city council proclaimed June 12th “Carl its renovation: the City of Aspen’s Historic Preservation Commission’s Bergman Day” in honor of a lifetime AHS annual Elizabeth Paepcke Award, recognizing projects that made an trustee who was instrumental in creating the outstanding contribution to historic preservation in Aspen; and the Holden/Marolt Mining & Ranching Museum. regional Caroline Bancroft History Project Award given annually by More than 300 community members gathered to History Colorado to honor significant contributions to the advancement remember Carl and enjoy a picnic and good-old- of Colorado history. Thanks to a marked increase in archive donations fashioned fun in his beloved place. over the past few years, the Collection surpassed 63,000 items in 2018, with an ever-growing online collection at archiveaspen.org. On that day, at the site of Pitkin County’s largest industrial enterprise in history, it was easy to see why AHS stewards your stories to foster a sense of community and this community supports Aspen Historical Society’s encourage a vested and informed interest in the future of this special work. Like Carl, the community understands that place. It is our privilege to do this work and we thank you for your Significant progress has been made on the renovation and restoration of three historic structures moved places tell the story of the people, the industries, and support. -

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

Photography: a Survey of New Reference Sources

RSR: Reference Services Review. 1987, v.15, p. 47 -54. ISSN: 0090-7324 Weblink to journal. ©1987 Pierian Press Current Surveys Sara K. Weissman, Column Editor Photography: A Survey of New Reference Sources Eleanor S. Block What a difference a few years make! In the fall 1982 issue of Reference Services Review I described forty reference monographs and serial publications on photography. That article concluded with these words, "a careful reader will be aware that not one single encyclopedia or solely biographical source was included... this reviewer could find none in print... A biographical source proved equally elusive" (p.28). Thankfully this statement is no longer valid. Photography reference is greatly advanced and benefited by a number of fine biographical works and a good encyclopedia published in the past two or three years. Most of the materials chosen for this update, as well as those cited in the initial survey article, emphasize the aesthetic nature of photography rather than its scientific or technological facets. A great number of the forty titles in the original article are still in print; others have been updated. Most are as valuable now as they were then for good photography reference selection. However, only those sources published since 1982 or those that were not cited in the original survey have been included. This survey is divided into six sections: Biographies, Dictionaries (Encyclopedias), Bibliographies, Directories, Catalogs, and Indexes. BIOGRAPHIES Three of the reference works cited in this survey have filled such a lamented void in photography reference literature that they stand above the rest in their importance and value. -

Download the Free Pdf of Volume I

9 volume 1 200 DiffusionUnconventional Photography Articles: Profiles: Group Showcase: I’m Often Asked... An Ironic Manifesto Jeffrey Baker Pamela Petro Formerly & Hereafter by Zeb Andrews by Dr. Mike Ware Tina Maas Sika Stanton Plates to Pixels Juried Show Praise for Diffusion, Volume I “Avant-garde, breakthrough and innovative are just three adjectives that describe editor Blue Mitchell’s first foray into the world of fine art photography magazines. Diffusion magazine, tagged as unconventional photography delivers on just that. Volume 1 features the work of Jeffrey Baker, Pamela Petro, Tina Maas and Sika Stanton. With each artist giving you a glimpse into how photography forms an integral part of each of their creative journey. The first issue’s content is rounded out by Zeb Andrews’ and Dr. Mike Ware. Zeb Andrews’ peak through his pin-hole world is complimented by an array of his creations along with the 900 second exposure “Fun Center” as the show piece. And Dr. Mike unscrambles the history of iron-based photographic processes and the importance of the printmaker in the development of a fine art image. At a time when we are seeing a mass migration to on-line publishing and on-line magazine hosting, the editorial team at Diffusion proves you can still deliver an outstanding hard-copy fine art photography magazine. I consumed my copy immediately with delight; now when is the next issue coming out?” - Michael Van der Tol “Regardless of the retrospective approach to the medium of photography, which could be perceived by many as a conservative drive towards nostalgia and sentimentality. -

Gretl Uhl – the "Strudel-Queen" from Garmisch-Partenkirchen

Gretl Uhl – the "Strudel-Queen" from Garmisch-Partenkirchen Gretl Hartl was born in Partenkirchen in 1923. She developed a passion for the mountains, and especially for skiing, very early on. Her parents ran a café at the Olympic Stadium in Garmisch. From 1941 onwards, Gretl also took part in official ski races, and ten years later she became a member of the German national team. During the war, from 1943 to 1945, she had worked on the Reichsbahn railway, but this did not stop her from continuing to ski. In 1948 Gretl Hartl married Sepp Uhl; they both shared the same passion for skiing. In 1951 Dick Durrance, a skier who would become very successful later on, arrived in Garmisch- Partenkirchen from Aspen, intending to present his film footage of the FIS World Cup in Colorado. Gretl and Sepp were invited to the presentation and were so delighted that they decided to emigrate to the famous American skiing town. After the Uhls found enough money to finance their crossing from Le Havre to New York and the train journey to Denver and on to Glenwood Springs, they set off, and arrived in Aspen, Colorado in November 1953. At first they lived there with their friend Wörndli in Alpine Lodge on Cooper Avenue. Later they rented a 45-dollar-a-month house on Main Street. Later on, Gretl emphasized continually that they had felt at home in Aspen from the very start, and that she and Sepp were immediately welcomed by the locals. They soon made the acquaintance of the famous skiing stars from Aspen. -

Modern Group Portraits in New York Exile Community and Belonging in the Work of Arthur Kaufmann and Hermann Landshoff

Modern Group Portraits in New York Exile Community and Belonging in the Work of Arthur Kaufmann and Hermann Landshoff Burcu Dogramaci In the period 1933–1945 the group portrait was an important genre of art in exile, which has so far received little attention in research.1 Individual works, such as Max Beckmann’s group portrait Les Artistes mit Gemüse, painted in 1943 in exile in Amsterdam,2 were indeed in the focus. Until now, however, there has been no systematic investigation of group portraits in artistic exile during the Nazi era. The following observations are intended as a starting point for further investigations, and concentrate on the exile in New York and the work of the emigrated painter Arthur Kaufmann and photographer Hermann Landshoff in the late 1930s and 1940s, who devoted themselves to the genre of group portraits. 3 New York was a destination that attracted a much larger number of emigrant artists, writers, and intellectuals than other places of exile, such as Istanbul or Shanghai. A total of 70,000 German-speaking emigrants who fled from National Socialism found (temporary) refuge in New York City, including—among many others—the painters Arthur Kaufmann and Lyonel Feininger, and the photographers Hermann Landshoff, Lotte Jacobi, Ellen Auerbach, and Lisette Model.4 Such an accumulation of emigrated artists and photographers in one place may explain the increasing desire to visualize group formats and communal compositions. In the genre of the group picture there are attempts to compensate for the displacement from the place of origin.5 This mode of self-portrayal as a group can be 1/15 found in the photographic New York group portraits where the exiled surrealists had their pictures taken together or with their American colleagues. -

ANNUAL UPDATE Winter 2020

ANNUAL UPDATE winter 2020 970.925.3721 | aspenhistory.org @historyaspen AN HISTORIC GUARANTEE, Executive Director’s Letter In 2019, Aspen Historical Society (AHS) doubled down on its mission to enrich the community through preserving and communicating our remarkable history with a special guarantee: “Learn something NEW, or we’ll give your money back to you!” This first-ever money back guarantee for all guided tours underscores what might seem obvious about the past: the stories are endless, especially when it comes to this community’s unique and often amusing history. It is AHS’s privilege to highlight and honor these stories – old and new – that define the upper Roaring Fork Valley’s collective identity. The final year of the decade brought a multitude of exciting opportunities to explore the past with AHS, from guided tours with historians and trained interpretive guides to four historic sites to one of the largest public archives in the region. Serving visitors and locals of all ages as a public resource, AHS guarantees we’ll continue to provide access to local history that fosters a sense of community and encourages a vested interest in the future of this special place. With a new decade upon us, this work remains as important as ever. Thanks to your continued support and participation, we look forward to continuing to celebrate the past, for the future. Sincerely, Kelly Murphy President & CEO MARGARET “MIGGS” DURRANCE Honoring Female Photographers in 2020 In honor of this year’s centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment that granted women the right to vote, the historical images in this piece feature women of the era taken by Margaret “Miggs” Durrance.* Miggs was a professional photographer who worked with her husband Dick while he pursued film projects; her work appeared in national magazines such as LIFE, Look, Sports Illustrated and National Geographic. -

ASSOCIATION for JEWISH STUDIES 38TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Manchester Grand Hyatt, San Diego, California December 17–19, 2006

ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES 38TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Manchester Grand Hyatt, San Diego, California December 17–19, 2006 Saturday, December 16, 2006, 8:00 PM Annie A WORKS IN PROGRESS GROUP IN MODERN JEWISH STUDIES Co-chairs: Todd S. Hasak-Lowy (University of Florida) Adam B. Shear (University of Pittsburgh) Sunday, December 17, 2006 GENERAL BREAKFAST 8:30 AM – 9:30 AM Manchester C (Note: By pre-paid reservation only.) REGISTRATION 8:30 AM – 6:00 PM Manchester Foyer AJS ANNUAL BUSINESS MEETING 8:30 AM – 9:00 AM Manchester A AJS BOARD OF 10:30 AM Maggie DIRECTORS MEETING BOOK EXHIBIT (List of Exhibitors p. 65) 1:00 PM – 6:30 PM Exhibit Hall Session 1, Sunday, December 17, 2006 9:30 AM – 11:00 AM 1.1 Manchester A PEDAGOGY AND POLITICS: TEACHING ISRAEL AT NORTH AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES TODAY Chair: Rivka B. Kern-Ulmer (Bucknell University) Discussants: Donna R. Divine (Smith College) Jonathan Goldstein (University of West Georgia) Shirah Hecht (JESNA) Th eodore Sasson (Brandeis University/Middlebury College) David B. Starr (Hebrew College) 1.2 Betsy A/B SOCIAL SCIENCE AND TEACHING ABOUT AMERICAN JEWRY Chair: Paul Burstein (University of Washington) Discussants: Claude Fischer (University of California, Berkeley) Shaul Kelner (Vanderbilt University) Shelly Tenenbaum (Clark University) 1.3 Edward A/B WHAT DOES JEWISH PHILOSOPHY CONTRIBUTE? THE CASES OF LEVINAS AND STRAUSS Chair: Sarah Hammerschlag (Williams College) Discussants: Martin Kavka (Florida State University) Kenneth R. Seeskin (Northwestern University) Eugene Sheppard (Brandeis University) Respondent: Leora F. Batnitzky (Princeton University) 21 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2006 9:30 AM – 11:00 AM 1.4 Ford A/B ASSESSING THE CHARACTERISTICS OF SYNAGOGUE TRANSFORMATION Chair: Jack Wertheimer (Jewish Th eological Seminary) Stories from Shul Ari Y. -

The Development and Growth of British Photographic Manufacturing and Retailing 1839-1914

The development and growth of British photographic manufacturing and retailing 1839-1914 Michael Pritchard Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Imaging and Communication Design Faculty of Art and Design De Montfort University Leicester, UK March 2010 Abstract This study presents a new perspective on British photography through an examination of the manufacturing and retailing of photographic equipment and sensitised materials between 1839 and 1914. This is contextualised around the demand for photography from studio photographers, amateurs and the snapshotter. It notes that an understanding of the photographic image cannot be achieved without this as it directly affected how, why and by whom photographs were made. Individual chapters examine how the manufacturing and retailing of photographic goods was initiated by philosophical instrument makers, opticians and chemists from 1839 to the early 1850s; the growth of specialised photographic manufacturers and retailers; and the dramatic expansion in their number in response to the demands of a mass market for photography from the late1870s. The research discusses the role of technological change within photography and the size of the market. It identifies the late 1880s to early 1900s as the key period when new methods of marketing and retailing photographic goods were introduced to target growing numbers of snapshotters. Particular attention is paid to the role of Kodak in Britain from 1885 as a manufacturer and retailer. A substantial body of newly discovered data is presented in a chronological narrative. In the absence of any substantive prior work this thesis adopts an empirical approach firmly rooted in the photographic periodicals and primary sources of the period. -

The Boys of Winter

Foreword Contents LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ix FOREWORD xi by Major John B. Woodward, Tenth Mountain Division (Ret.) PREFACE xv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xvii 1 The Hero of the Thunderbolt (Rudy Konieczny) 1 2 The Pied Piper of Pine Lake (Jake Nunnemacher) 20 3 The Sun Valley Serenader (Ralph Bromaghin) 41 4 The Time of Their Lives 58 5 Rocky Mountain Highs 73 6 From Alaska to Austin 89 7 General Clark and the War in Italy 107 8 Good-byes 112 9 Into the Maelstrom 117 10 The Ridges That Could Not Be Taken 128 11 The Brutal Road to Castel d’Aiano 144 12 Rest and Recuperation 155 13 The Bloodbath of Spring 164 14 Bad Times 173 vii ForewordContents 15 Pursuit to the Alps 190 16 Home 193 17 Legacy 199 NOTES 205 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 239 ABOUT THE AUTHOR 243 INDEX 245 viii The Hero of the Thunderbolt (Rudy Konieczny) C H A P T E R O N E The Hero of the Thunderbolt (Rudy Konieczny) THE STORMS ROLLED ACROSS WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS IN FEBRUARY 1936 AS they always had, leaving a blanket of white on the hills around Adams that turned luminous under the full moon. Down the road in the southern Berk- shires, Norman Rockwell was capturing on canvas the idealized images of small-town life in Depression-era America. On this night, he would have done well to travel a few miles north for his inspiration. On the wooded slopes behind the old Konieczny farm in Adams, several young men shivered in the moonlight, shouldering their seven-foot hickory skis toward the modest summit. -

MEISTER Utah Olympic Park, Park City, Utah PAGE4 Vintage Skiwear

Alf Engen Ski Museum Foundation Ski MEISTER Utah Olympic Park, Park City, Utah PAGE 4 PAGE Vintage Skiwear Fashion Show New Board Member: Todd Engen 7 PAGE PAGE 3 PAGE Honoring the 2002 Olympic Meet the New Volunteers Hall of Fame Inductees PAGE 10 PAGE WINTER 2019-20 Preserving the rich history of snow sports in the Intermountain West engenmuseum.org CHAIRMAN’S LETTER It’s hard to believe it would have been Alf Engen’s 110th birthday this year! Hello, everyone, and thank you so much for your support of our wonderful Alf Engen Ski Museum. We take a lot of pride in being one of the finest ski mu- seums in the world, thanks to your ongoing dedication. If you’ve been to the museum lately, you know that we have very high Board of Trustees standards for our exhibits. Our upgraded Alf Engen and Stein Eriksen exhibits Tom Kelly attracted much attention this past year as around a half million people came Chairman through our doors. David L. Vandehei To enhance those standards, our Executive Director, Connie Nelson and Chairman Emeritus Operations Manager, Jon Green, are actively engaged with StEPs (Standards Alan K. Engen and Excellence Program for History Organizations), now halfway through the two-year program. We were Chairman Emeritus especially proud of Connie this year when she was recognized with the International Skiing History Associa- Scott C. Ulbrich tion’s Lifetime Achievement Award. Chairman Emeritus You may also have noticed a concerted effort to tell our story through social media, with daily Facebook, Mike Korologos Instagram and Twitter posts, showcasing our wonderful archive of historical artifacts and interesting stories. -

Photography in Lancaster

The Art o/ Photography in Lancaster By M. LATHER HEISEY HEN Robert Burns said: "0 wod some Pow'r the giftie gie W us, to see oursels as ithers see us !" he did not realize that one answer to his observation would be given to the world by the invention of photography. Until that time men saw their images "as through a glass darkly," by the medium of skillfully painted portraits by the old masters, by reflections in mirrors, placid streams or highly polished surfaces. Years before 1839, artists and chemists had been experiment- ing with methods to retain a permanent image or reflection of an object upon a canvass or other surface. In August of that year photography "came to light" when Louis J. M. Daguerre (1789- 1851) first publicly announced his process in Paris. "Daguerre, a French painter of dioramas, astonished the scientific world by pro- ducing sun pictures obtained by exposing the surface of a highly polished silver tablet to the vapor of iodine in a dark room, and then placing the tablet in a camera obscuro, and exposing it to the sunlight. A latent image of the object within the range of the camera was thus obtained, and this image was developed by expos- ing the tablet to the fumes of mercury, heated to a temperature of about 170° Fahrenheit. The image thus secured was 'fixed' or made permanent by dipping the tablet into a solution of hyposul- phite of soda, and then carefully washing and drying the plate." 1 The development of photography to the perfection of the pres- ent time was, like all inventions, a slow and steady advance.