Getting Started with Songwriting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song List for Bandaoke

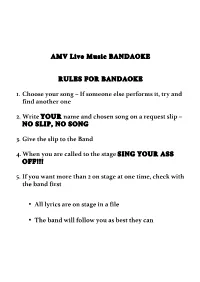

AMV Live Music BANDAOKE RULES FOR BANDAOKE 1. Choose your song – If someone else performs it, try and find another one 2. Write YOUR name and chosen song on a request slip – NO SLIP, NO SONG 3. Give the slip to the Band 4. When you are called to the stage SING YOUR ASS OFF!!! 5. If you want more than 2 on stage at one time, check with the band first • All lyrics are on stage in a file • The band will follow you as best they can SONG LIST FOR BANDAOKE A Addicted to love – Robert Palmer Aint no sunshine – Bill Withers Aint Nobody – Chaka khan Alright now – Free All day and all of the night – The Kinks Amarillo – Tony Christie American Boy - Estelle American Pie – Don McClean Angels – Robbie Williams At Last – Etta James B Beat It – Michael Jackson Better Together – Jack Johnson Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Bitch – Meredith Brooks Black and Gold – Sam Sparro Black Velvet – Alannah Miles Blueberry Hill – Fats Donimo Born to be wild – Steppenwolf Breakfast at Tiffanys – Deep Blue Something Brown eyed girl – Van Morrison Brown Sugar – Rolling stones Build me up buttercup – The foundations C Can’t get enough of your love – Bad Company Can’t take my eyes of you – Andy Williams/Frank Sinatra Chasing cars – Snow Patrol Chelsea Dagger – The Fratellis Come away with me – Norah Jones Come Together – The Beatles Crazy – Gnarles Barkley Crazy little thing called love – Queen D Daydream believer – The Monkees Daytripper – The Beatles Desperado – The Eagles Dock of the bay – Otis Redding Don’t know why – Norah Jones Don’t let the sun go down on me – -

70S Playlist 1/7/2011

70s Playlist 1/7/2011 Song Artist(s) A Song I Like to Sing K. Kristoferson/L Coolidge Baby Come Back Steve Perry Bad, Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Don't Stop Fleetwood Mac Father and Son Cat Stevens For my lady Moody Blues Have you seen her The Chi-Lites I Have to say I love you in a Son Jim Croce I want Love Elton John If you Remember Me Kris Kristofferson It's only Love Elvis Presley I've got a thing about you baby Elvis Presley Magic Pilot Moon Shadow Cat Stevens Operator (That's Not the Way it Jim Croce Raised on a Rock Elvis Presley Roses are Red Freddy Fender Someone Saved My Life Tonigh Elton John Steamroller Blues Elvis Presley Stranger Billy Joel We're all alone K. Kristoferson/L Coolidge Yellow River Christie Babe Styx Dancin' in the Moonlight King Harvest Solitaire The Carpenters Take a Walk on the Wild Side Lou Reed Angel of the Morning Olivia Newton John Aubrey Bread Can't Smile Without You Barry Manilow Even Now Barry Manilow Top of the World The Carpenters We've only Just Begun The Carpenters You've Got a Friend James Taylor A Song for You The Carpenters ABC The Jackson 5 After the Love has Gone Earth, Wind and Fire Ain't no Sunshine Bill Withers All I Ever Need is You Sonny and Cher Another Saturday Night Cat Stevens At Midnight Chaka Khan At Seventeen Janis Ian Baby, that's Backatcha Smokey Robinson Baby, I love Your Way Peter Frampton Band on the Run Paul McCartney Barracuda Heart Beast of Burden The Rolling Stones Page 1 70s Playlist 1/7/2011 Song Artist(s) Beautiful Sunday Daniel Boone Been to Canaan Carol King Being -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Jukebox Titles Index Winter � 2015

Jukebox Titles Index Winter - 2015 th Valid from 7 December www.jukebox-hire.co.uk [email protected] 07860 516 973 Hint – to search for a particular song in this PDF file simply use ‘Ctrl’ and ‘F’ 01 I Grew Up in the 80’s – The No.1s 03 Made in the 90s CD – 1 01 Frankie Goes To Hollywood - Relax 01. All Saints - Never Ever 02 Black Box - Ride On Time 02. En Vogue - Don't Let Go (Love) 03 Yazz - The Only Way Is Up 03. Brandy & Monica - The Boy Is Mine 04 The Human League - Don't You Want Me 04. Jennifer Paige - Crush 05 Mel & Kim - Respectable 05. Sixpence None The Richer - Kiss Me 06 Dexy's Midnight Runners - Come On Eileen 06. Gabrielle - Dreams 07 The Jam - Town Called Malice 07. Eternal Ft. Bebe Winans - I Wanna Be the Only One 08 Duran Duran - The Reflex 08. Salt - N 09 Kajagoogoo - Too Shy 09. Mark Morrison - Return Of The Mack 10 Culture Club - Karma Chameleon 10. Jade - Don't Walk Away 11 Soul II Soul Ft Caron Wheeler - Back To Life 11. Shanice - I Love Your Smile 12 Blondie - The Tide Is High 12. Lenny Kravitz - It Ain't Over 'Til It's Over 13 UB40 - Red Red Wine 13. Lighthouse Family - High 14 The Specials - Ghost Town 14. Sweetbox - Everything's Gonna Be Alright 15 Foreigner - I Want To Know What Love Is 15. Shola Ama - You Might Need Somebody 16 Kylie Minogue & Jason Donovan - Especially For You 16. Honeyz - Finally Found 17 Spandau Ballet - True 17. -

American Girl

Markelele’s Ukulele Songbook 18 January 2015 The lyrics & chords listed here are provided for private education and information purposes only. You are advised to confirm your compliance with the appropriate local copyright regulations before using any of the material provided. The lyrics, chords & tabs sheets represent interpretations of the material and may not be identical to the original versions, which are copyright of their respective owners. http://rawsthorne.weebly.com/index.html Contents Ukulele Chords ................................................ 5 (Don’t Make Me Play) When I’m Cleaning Ukulele Fretboard ............................................ 6 Windows........................................................ 64 Circle of Fifths .................................................. 7 Don’t Need The Sun To Shine (To Make Me 12 Bar Blues For Uke ....................................... 8 Smile) ............................................................ 65 Fingerpicking The Blues in A ......................... 15 Don’t Worry, Be Happy ................................. 66 Ace Of Spades ............................................... 16 Don’t You Want Me ....................................... 67 Add Me .......................................................... 17 Drift Away ...................................................... 68 Ain’t Misbehavin’ ............................................ 18 Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Ain't No Sunshine........................................... 19 Shouldn't've) ................................................. -

Take a New Turn Worries? He Said He Doesn’T Enjoy Auburn 2

Check out 2015 Bid the antelope Day photos on page 8 Volume 117, Issue 1 | 9.2.15 | www.unkantelope.com Kleinberg to speak Five Things To Do When Sept. 8 on his book, You’re A Freshman SURVIVOR RACHEL SLOWIK Holocaust experience Antelope Staff YRACEMA RIVAS purpose because there are similarities a very likable person,” Carstensen said. The transition from Antelope Staff with Kleinberg’s story college students can Senior lecturer Jake Jacobsen has high school to college identify with. been impressed with Kleinberg since can be tough. I know In his life he has seen the unthinkable. “While Milton’s story and past they first met through Carstensen, who first hand. First there “If you live, you live to see it all,” circumstances are far more severe than kept in touch after completing Jacobsen’s is the whole saying Nebraska businessman and author, Milton most people can comprehend, there are UNK Advanced Communications class. goodbye to mom and dad on Move-In Kleinberg says about his journey from the several similarities that college students He encouraged Jacobsen to read the Day. Then there is the first day of classes, Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 through can relate to. College can be a very stressful book, and Jacobsen became determined and it feels weird going to three classes his years in war camps and his post-war and difficult time for many,” Carstensen to bring Kleinberg to UNK. each day, instead of the eight classes you emigration to the U.S. said. “Students undergo so much change in Jacobsen said, “What I met was a had in high school. -

Jazz and Swing Standards

Jazz and Swing Standards I'll be seeing you Fever Dream a little dream of me Summertime Someone to watch over me If I were a bell They can't take that away from me Embraceable you I get a kick out of you L.O.V.E. It had to be you Fly me to the moon Our love is here to stay The way you look tonight Cry Me a River Smile A Fine Romance Sway Till there was you You go to my head Smoke gets in your eyes Don't Know Why Sway Cry Me a River I get a kick out of you It had to be you Cheek to cheek The Man I love- B Flat I Wanna Be Around I Left My Heart in San Francisco Some Other Time Till There Was You It Had to Be You Don't Get Around Much Anymore The good life Rags to riches Till there was you Misty Honeysuckle rose Cheek to cheek Aint misbehaving I will wait for you I'm in the mood for love Don't get round much anymore All of me Satin doll When you're smiling Smile As time goes by Autumn leaves Smoke gets in your eyes What a wonderful world Summer wind Over the rainbow Fly me to the moon The best is yet to come Come fly with me The way you look tonight New York new York My way Aint that a kick in the head Have you met miss jones Sway Thats amore It's only a paper moon Exactly like you Orange coloured sky Almost like being in love What a difference a day made Moon dance 1950’s A teenager in love Don't start me talking Fever Tequila My baby just cares for me Aint that a shame Train kept a rollin I got a woman Take five Reet petite Got my mojo working Jambalaya Tennessee waltz Rock and roll music Bebop a lula Rock around the clock Earth angel All -

WCXR 2004 Songs, 6 Days, 11.93 GB

Page 1 of 58 WCXR 2004 songs, 6 days, 11.93 GB Artist Name Time Album Year AC/DC Hells Bells 5:13 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Back In Black 4:17 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 3:30 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Have a Drink on Me 3:59 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:12 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC Squealer 5:14 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC Big Balls 2:38 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) 5:44 For Those About to R… 1981 AC/DC Highway to Hell 3:28 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Girls Got Rhythm 3:24 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Beating Around the Bush 3:56 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Let There Be Rock 6:07 Let There Be Rock 1977 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 5:23 Let There Be Rock 1977 Ace Frehley New York Groove 3:04 Ace Frehley 1978 Aerosmith Make It 3:41 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Somebody 3:46 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Dream On 4:28 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith One-Way Street 7:02 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Mama Kin 4:29 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Rattkesnake Shake (live) 10:28 Aerosmith 1971 Aerosmith Critical Mass 4:52 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Draw The Line 3:23 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Milk Cow Blues 4:11 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Livin' on the Edge 6:21 Get a Grip 1993 Aerosmith Same Old Song and Dance 3:54 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Lord Of The Thighs 4:15 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Woman of the World 5:50 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Train Kept a Rollin 5:33 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Seasons Of Wither 4:57 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Lightning Strikes 4:27 Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Aerosmith Last Child 3:28 Rocks 1976 Aerosmith Back In The Saddle 4:41 Rocks 1976 WCXR Page 2 of 58 Artist Name Time Album Year Aerosmith Come Together 3:47 Sgt. -

: ,·· ..•' •;: ~{: ... ;·:.·.~ . ~~.·, :F '·.,;':':''' ';.' .. ': : ,. '

ROLLING STONE, OCTOBER 24, 19'74 73 j' .- ·-· .: ,· ·.. •' •;: ~{: ... ; ·: .·.~.. ~~.·, _ :f '·.,;':':''' ';.' .. ': : ,. ' . ' "'· ,ll ,. ' J_-' >:.• U· ".· • boardist Bill Payqe and slide guitarist I singer ' Lowell George. By the group's second album; Sllilin' Shoes, George's voice and guitar had pro gressed to the point where Lit tle Feat was no longer just· a writers' bandr Material, per- : formance and production were held in equipoise through . that all~um and its successor, :Dixie Chicken. On Feats Don't , fail Me '!vow that. perf~ct ten-· Starting Over · sion has slackened. Now the Raspberries .: band's stre~gth 'fl~ driven out Capitol ST 11329 the quirky but affecting vision. · . that made Little Feat unique By Ken Barnes · · and worth ~herishing. The . outfit is a superb, well-oiled The Raspberries have at la~t machine but with some of the realized.-thi:ir potential.' impersonality which such a They've cleai:Iy become( the characterizatio'n implies. premier synthesizer$-of ,Sixties Little Feat has had a ter~ . pop influences extant. Ev_en ' : ribly checkl!red history; 'f'ith · more importantly, the end.re.- near 'breakups .. o,ccurring not sults of their adn.>it collages· of quite as frequemiy as·damag._ musical knowledge often equal ing rumors ·said · they were. or surpass their models' orig- George hopes he ltas· finally . ina! cre11tions~ achieved a measure of -stabil- AS. illt~strations there are . jty! .He is ~ot qulte as domi two perfectly. astonishing.; nimt as he once waS,:,....he has tracks ·on Starting Over. "I 'conscimisly 'down, played hii,. ·Don't Know What I Want" is own ·ai.•thority....:.:.~;>ut this may the ultirtuite Who tribute, a su not be the root'of the problem. -

Track Title Artist It's Now Or Never Acoustic Moods Ensemble Stranger

Track Title Artist It's Now Or Never Acoustic Moods Ensemble Stranger on the Shore Acoustic Moods Ensemble Love Is a Losing Game Acoustic Moods Ensemble As Tears Go BY Acoustic Moods Ensemble Martha's Harbour Acoustic Moods Ensemble Guantanamera Acoustic Moods Ensemble Golden Brown Acoustic Moods Ensemble Because The Night Acoustic Moods Ensemble Make It Easy on Yourself Acoustic Moods Ensemble Walk on By Acoustic Moods Ensemble Something Stupid Acoustic Moods Ensemble Cavatina Acoustic Moods Ensemble Summer Breeze Acoustic Moods Ensemble Miss You Nights Acoustic Moods Ensemble Save the Last Dance For Me Acoustic Moods Ensemble Hotel California Acoustic Moods Ensemble Wonderful Tonight Acoustic Moods Ensemble Something Acoustic Moods Ensemble While My Guitar Gently Weeps Acoustic Moods Ensemble Lay Lady Lay Acoustic Moods Ensemble Fields Of Gold Acoustic Moods Ensemble The Wind Beneath My Wings Acoustic Moods Ensemble Wonderful Land Acoustic Moods Ensemble Time In a Bottle Acoustic Moods Ensemble And I Love Her Acoustic Moods Ensemble Yesterday Acoustic Moods Ensemble Here, There and Everywhere Acoustic Moods Ensemble Moon River Acoustic Moods Ensemble Nights In White Satin Acoustic Moods Ensemble Blue Moon Acoustic Moods Ensemble Wonderwall Acoustic Moods Ensemble La Isla Bonita Acoustic Moods Ensemble The Sound of Silence Acoustic Moods Ensemble Time After Time Acoustic Moods Ensemble I Don’t Want to Talk About IT Acoustic Moods Ensemble I'll Stand By You Acoustic Moods Ensemble In Sleep I Dream Of You Acoustic Moods Ensemble In The -

Artist Song Title Song

ARTIST SONG TITLE SONG # ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears 8-451 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 9-529 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 8-324 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 8-325 10cc I'm Not In Love 3-163 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10-207 112 Dance With Me (Radio Version) 6-575 112 Peaches And Cream (Radio Version) 6-589 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 6-099 12 Stones We Are One 11-001 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1, 2, 3 Red Light 7-091 2 Live Crew Me So Horny 1-589 2 Live Crew We Want Some P###y 7-480 2 Pac California Love (Original Version) 2-002 2 Pac Changes 6-126 2 Pac Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) 6-149 20 Fingers Short #### Man 6-576 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 7-302 3 Doors Down Be Like That (Radio Version) 9-272 3 Doors Down Here Without You 9-280 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 5-374 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3-344 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 7-317 3 Doors Down Live For Today 9-285 3 Doors Down Loser 6-521 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 9-298 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3-357 3 Doors Down When You're Young 11-002 311 All Mixed Up 3-301 311 Down 9-250 311 Love Song 10-356 38 Special Caught Up In You 9-068 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night 7-352 38 Special Teacher, Teacher 7-292 38 Special Wild-Eyed Southern Boys 7-594 3LW No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) (Radio Version) 7-199 3oh3 Feat Ke$ha My First Kiss 11-003 4 Non Blondes What's Up 9-510 42nd Street (Broadway Version) 42nd Street 10-182 42nd Street (Broadway Version) We're In The Money 3-478 50 Cent If I Can't 6-109 50 Cent In Da Club 2-044 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 7-465 50 Cent P.I.M.P. -

Sample Song List

The Masqueraders song list by genre POP/CLASSICS Addicted To Love – Robert Palmer All You Need Is Love – The Beatles American Pie – Don Maclean Billy Jean – Michael Jackson Blue Suede Shoes – Elvis Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Build Me Up Buttercup – The Foundations Can’t Help Falling In Love With You - Elvis Can’t Take My Eyes Off You –Andy Williams Come Together – The Beatles Daydream Believer – The Monkees Delila - Tom Jones Don’t Dream It’s Over – Crowded House Don’t Let Me Down – The Beatles Don’t You Want Me Baby – Human League Every Breath You Take – The Police Gimme Some Lovin’ – Blues Brothers Hard To Handle – Ottis Reading Have I Told You Lately – Van Morrison Hey Jude – The Beatles Higher and Higher – Jackie Wilson Holiday - Madonna Hound Dog – Elvis How Sweet It Is To Be Loved By You – James Taylor I Heard It Through The Grapevine – Marvin Gaye I Just Can’t Stop Loving You – Michael Jackson I’m A Believer – The Monkees Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder Jailhouse Rock – Elvis Knock On Wood – Eddie Floyd La Bamba – Ritchie Valens Learning To Fly – Tom Petty Let’s Stay Together – Al Green Lets Stick Together – Bryan Ferry Like A Virgin - Madonna Maggie May – Rod Steward Mama Mia – Abba Midnight Hour – Wilson Pickett Moondance- Van Morrison Motown Medley Mustang Sally - The Commitments My Girl – The Temptations No Woman No Cry – Bob Marley Nothings Gonna Change My Love For You – George Benson Perfect – Fairground Attraction Rio – Duran Duran Saw Her Standing There – The Beatles Sos – Abba Soul Man – Blues Brothers Stand By Me