Ancient Roots: Mythology and Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

The Function of Lethe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Flinders Academic Commons This is an electronic version of an article published in M. Baker and D. Glenn (eds) 2000. ‘Dante Colloquia in Australia: 1982-1999’, Australian Humanties Press: Adelaide. Coassin, Flavia 2000. The Function of Lethe. In M. Baker and D. Glenn (eds). ‘Dante Colloquia in Australia: 1982-1999’, Australian Humanties Press: Adelaide, 95-102. THE FUNCTION OF LETHE FLAVIA COASSIN WHEN, in the last canto of the Purgatorio, Dante-character claims not to remember having ever estranged himself from Beatrice, she reminds him that he has just drunk of Lethe, and adds that his inability to remember is proof of his estrangement, just as from smoke fire is inferred: "E se tu ricordar non te ne puoi," sorridendo rispuose, "or ti rammenta come bevesti di Letè ancoi; e se dal fummo foco sargomenta, cotesta oblivion chiaro conchiude colpa ne la tua voglia altrove attenta". (Purg. XXXIII, 94-99) According to Reggio, l who also quotes Chimenz, the comparison is insubstantial, because there is no logical connection between oblivion and sin as there is between smoke and fire, and thus oblivion does not count as proof, his assumption being that there could be oblivion without sin. This assumption, however, is incorrect. In Dantes poem, as well as in the classical myths concerning the afterlife, we find that the connection between the two is, on the contrary, one of cause and effect. It is not by coincidence that the episode in question (lines 91-129) contains two instances of forgetfulness, namely, of having sinned and of Mateldas previous explanation of the function of the two rivers. -

Greek and Roman Perceptions of the Afterlife in Homer's

McNair Scholars Journal Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 2 2007 Greek and Roman Perceptions of the Afterlife in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid Jeff Adams Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Adams, Jeff (2007) Gr" eek and Roman Perceptions of the Afterlife in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol11/iss1/2 Copyright © 2007 by the authors. McNair Scholars Journal is reproduced electronically by ScholarWorks@GVSU. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ mcnair?utm_source=scholarworks.gvsu.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol11%2Fiss1%2F2&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages Greek and Roman Perceptions of the Afterlife in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid Abstract Homer’s Odyssey says that death “is the This study is a literary analysis of way of mortals, whenever one of them Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s should die, for the tendons no longer Aeneid. Of specific interest are the hold flesh and bones together, but the interactions of Achilles, Odysseus, strong might of blazing fire destroys and Aeneas with their beloved dead. these things as soon as the spirit has left I focused on what each party, both the the white bones, and the soul, having living and the dead, wanted and the flown away like a dream, hovers about.”1 results of their interaction. Methods People have always been fascinated by included reading passages from the death and the afterlife. -

Underworld Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2018 Underworld Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. 2019. "Underworld." In Oxford Classical Dictionary. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/123 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Underworld Radcliffe G. Edmonds III In Oxford Classical Dictionary, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. (Oxford University Press. April 2019). http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8062 Summary Depictions of the underworld, in ancient Greek and Roman textual and visual sources, differ significantly from source to source, but they all draw on a common pool of traditional mythic motifs. These motifs, such as the realm of Hades and its denizens, the rivers of the underworld, the paradise of the blessed dead, and the places of punishment for the wicked, are developed and transformed through all their uses throughout the ages, depending upon the aims of the author or artist depicting the underworld. Some sources explore the relation of the world of the living to that of the dead through descriptions of the location of the underworld and the difficulties of entering it. By contrast, discussions of the regions within the underworld and existence therein often relate to ideas of afterlife as a continuation of or compensation for life in the world above. -

Lecture 8 Alexander WC 107-122 PP 138-144: Aristotle, Politics and Plutarch on Alex

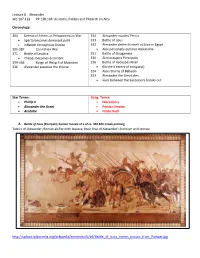

Lecture 8 Alexander WC 107-122 PP 138-144: Aristotle, Politics and Plutarch on Alex Chronology: 404 Defeat of Athens in Peloponnesian War 334 Alexander invades Persia Sparta becomes dominant polis 333 Battle of Issus inflation throughout Greece 332 Alexander deifies himself at Siwa in Egypt 395-387 Corinthian War Alex personally outlines Alexandria 371 Battle of Leuctra 331 Battle of Gaugamela Thebes becomes dominant 330 Alex occupies Persepolis 359-336 Reign of Philip II of Macedon 326 Battle of Hydaspes River 336 Alexander assumes the throne (farthest extent of conquest) 324 Alex returns of Babylon 323 Alexander the Great dies wars between the Successors breaks out Star Terms: Geog. Terms: Phillip II Macedonia Alexander the Great Persian Empire Aristotle Hindu Kush A. Battle of Issus (Pompeii), Roman mosaic of a of ca. 310 BCE Greek painting Tactics of Alexander; Roman ability with tessera; their love of Alexander’s heroism and stories; http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b9/Battle_of_Issus_roman_mosaic_from_Pompei.jpg Lecture 8 Alexander B. Demosthenes, Roman copy after a bronze original of c. 280 BCE, marble using art to capture a likeness and personality/ Demosthenes/ realistic depiction vs. an idealized one This statue was one of several Athenian heroes opposed to the Macedonian rule of Athens that was set up in the agora, or marketplace, of the city. Demosthenes was forced by the Macedonians to flee Athens. When he reached the island of Poros, he drank poison rather than submit to the enemy. An inscription on the base of the sculpture reads: ‘If your strength had equaled your resolution, Demosthenes, the Macedonian Ares [i.e. -

Interpv31issue1 1 29 04 (Page 1)

Volume 31 Issue 1 Interpretation, Inc. 11367-1597 U.S.A. Flushing, N.Y. Queens College 31/1 A JOURNAL OF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Interpretation Fall 2003 3 Ronald Hamowy Two Whig Views of the American Revolution: Adam Ferguson’s Response to Richard Price Discussion: 37 Patrick Coby Mind Your Own Business: The Trouble with Justice in Plato’s Republic 59 Sean Steel Katabasis in Plato’s Symposium Book Reviews: 85 Martin Yaffe The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis by Leon R. Kass 93 Mera Flaumenhaft Colloquial Hermeneutics: Eva Brann’s Odyssey 103 Wayne Ambler Our Attraction to Justice Devin Stauffer The Idea of Enlightenment: Hanover, PAHanover, 17331 109 Fall 2003 Fall U.S. POSTAGE U.S. POSTAGE Non-Profit Org. A Post-Mortem Study by Permit No. 4 Robert C. Bartlett PAID A JOURNAL OF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Editor-in-Chief Hilail Gildin, Dept. of Philosophy, Queens College Associate Editor Erik Dempsey General Editors Seth G. Benardete (d. 2001) • Charles E. Butterworth • Hilail Gildin • Leonard Grey • Robert Horwitz (d. 1978) • Howard B. White (d. 1974) Consulting Editors Christopher Bruell • Joseph Cropsey • Ernest L. Fortin (d. 2002) • John Hallowell (d. 1992) • Harry V. Jaffa • David Lowenthal • Muhsin Mahdi • Harvey C. Mansfield • Arnaldo Momigliano (d. 1987) • Michael Oakeshott (d. 1990) • Ellis Sandoz • Leo Strauss (d. 1973) • Kenneth W. Thompson International Editors Terence E. Marshall • Heinrich Meier Editors Wayne Ambler • Maurice Auerbach • Robert Bartlett • Fred Baumann • Amy Bonnette • Eric Buzzetti • Susan Collins • Patrick Coby • Elizabeth C’de Baca Eastman • Thomas S. Engeman • Edward J. Erler • Maureen Feder-Marcus • Pamela K. Jensen • Ken Masugi • Carol M. -

Lecture 17 Spartan Hegemony and the Persian Hydra

3/15/2012 Lecture 17 Spartan Hegemony and the Persian Hydra HIST 332 Spring 2012 The Aftermath of the Peloponnesian War • General – Greece in a state of economic and demographic devastation; proliferation of mercenaries. • Athens - starved into submission: – Demolish the Long Walls – Surrender all ships except 12 – Accept the lead of Sparta – An oligarchic government by 30 men is put in place by Lysander – Democracy is abolished • Rule of the Thirty Tyrants • Ionian Greeks – Under Persian control. • Sparta –hegemon of Greece; – imposes harmosts & garrisons on defeated cities – allied to the Persians. 4th century Greece Period of continuous warfare • The Corinthian War (394-386 BCE). • Thebes and Sparta (377-362 BCE). • The Social War (357-355 BCE). • The hegemony of Macedon. 1 3/15/2012 Spartan general Lysander Probably of noble descent but impoverished • Lover of prince Agesilaos • Ambitious and Un-Spartan in some ways: – understood way to defeat Athens was to create a navy – He created a bond with the Persian prince Cyrus, son of king Darius II • funded the Spartan fleet • Power-hungry – not enough to stage open revolt against the Spartan constitution Agesilaos II (401-360) A towering figure in Spartan history • Eurypontid king when Sparta ruled Greek world – Half-brother of king Agis II • Very popular among the men in the army, very influential – He had undergone the agoge despite his lame leg – hated Thebes • influenced many wrong decisions – largely responsible for the decline of Spartan power – impoverish the Spartan treasury • -

Heroic Death in Ancient Greek Poetry and Art

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department 2009 The Hero Beyond Himself: Heroic Death in Ancient Greek Poetry and Art Corinne Ondine Pache Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation Pache, C.O. (2009). The hero beyond himself: Heroic death in ancient Greek poetry and art. In S. Albersmeier (Ed.), Heroes: Mortals and myths in ancient Greece (pp. 88-107). Walters Art Museum. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In all those stories the hero is beyond himself into the next thing, be it those labors of Hercules, or Aeneas going into death. I thought the instant of the one humanness in Virgil's plan of it was that it was of course human enough to die, yet to come back, as he said, hoc opus, hie labor est. That was the Cumaean Sibyl speaking. This is Robert Creeley, and Virgil is dead now two thousand years, yet Hercules and the Aeneid, yet all that industrious wis- dom lives in the way the mountains and the desert are waiting for the heroes, and death also can still propose the old labors. -Robert Creeley, "Heroes" HEROISM AND DEATH The modern mind likes its heroism served with death. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective.