The Eђects of Fragmentation on Fluctuating Asymmetry in Passerine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds of Reserva Ecológica Guapiaçu (REGUA)

Cotinga 33 The birds of Reserva Ecológica Guapiaçu (REGUA), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Leonardo Pimentel and Fábio Olmos Received 30 September 2009; final revision accepted 15 December 2010 Cotinga 33 (2011): OL 8–24 published online 16 March 2011 É apresentada uma lista da avifauna da Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu (REGUA), uma reserva privada de 6.500 ha localizada no município de Cachoeiras de Macacu, vizinha ao Parque Estadual dos Três Picos, Estação Ecológica do Paraíso e Parque Nacional da Serra dos Órgãos, parte de um dos maiores conjuntos protegidos do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Foram registradas um total de 450 espécies de aves, das quais 63 consideradas de interesse para conservação, como Leucopternis lacernulatus, Harpyhaliaetus coronatus, Triclaria malachitacea, Myrmotherula minor, Dacnis nigripes, Sporophila frontalis e S. falcirostris. A reserva também está desenvolvendo um projeto de reintrodução dos localmente extintos Crax blumembachii e Aburria jacutinga, e de reforço das populações locais de Tinamus solitarius. The Atlantic Forest of eastern Brazil and Some information has been published on neighbouring Argentina and Paraguay is among the birds of lower (90–500 m) elevations in the the most imperilled biomes in the world. At region10,13, but few areas have been subject to least 188 bird species are endemic to it, and 70 long-term surveys. Here we present the cumulative globally threatened birds occur there, most of them list of a privately protected area, Reserva Ecológica endemics4,8. The Atlantic Forest is not homogeneous Guapiaçu (REGUA), which includes both low-lying and both latitudinal and longitudinal gradients parts of the Serra dos Órgãos massif and nearby account for diverse associations of discrete habitats higher ground, now mostly incorporated within and associated bird communities. -

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

Abstract Book

Welcome to the Ornithological Congress of the Americas! Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina, from 8–11 August, 2017 Puerto Iguazú is located in the heart of the interior Atlantic Forest and is the portal to the Iguazú Falls, one of the world’s Seven Natural Wonders and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The area surrounding Puerto Iguazú, the province of Misiones and neighboring regions of Paraguay and Brazil offers many scenic attractions and natural areas such as Iguazú National Park, and provides unique opportunities for birdwatching. Over 500 species have been recorded, including many Atlantic Forest endemics like the Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata), the emblem of our congress. This is the first meeting collaboratively organized by the Association of Field Ornithologists, Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia and Aves Argentinas, and promises to be an outstanding professional experience for both students and researchers. The congress will feature workshops, symposia, over 400 scientific presentations, 7 internationally renowned plenary speakers, and a celebration of 100 years of Aves Argentinas! Enjoy the book of abstracts! ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIR: Valentina Ferretti, Instituto de Ecología, Genética y Evolución de Buenos Aires (IEGEBA- CONICET) and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Andrés Bosso, Administración de Parques Nacionales (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable) Reed Bowman, Archbold Biological Station and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Gustavo Sebastián Cabanne, División Ornitología, Museo Argentino -

Predation on Vertebrates by Neotropical Passerine Birds Leonardo E

Lundiana 6(1):57-66, 2005 © 2005 Instituto de Ciências Biológicas - UFMG ISSN 1676-6180 Predation on vertebrates by Neotropical passerine birds Leonardo E. Lopes1,2, Alexandre M. Fernandes1,3 & Miguel Â. Marini1,4 1 Depto. de Biologia Geral, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2 Current address: Lab. de Ornitologia, Depto. de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 3 Current address: Coleções Zoológicas, Aves, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Avenida André Araújo, 2936, INPA II, 69083-000, Manaus, AM, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 4 Current address: Lab. de Ornitologia, Depto. de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade de Brasília, 70910-900, Brasília, DF, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We investigated if passerine birds act as important predators of small vertebrates within the Neotropics. We surveyed published studies on bird diets, and information on labels of museum specimens, compiling data on the contents of 5,221 stomachs. Eighteen samples (0.3%) presented evidence of predation on vertebrates. Our bibliographic survey also provided records of 203 passerine species preying upon vertebrates, mainly frogs and lizards. Our data suggest that vertebrate predation by passerines is relatively uncommon in the Neotropics and not characteristic of any family. On the other hand, although rare, the ability to prey on vertebrates seems to be widely distributed among Neotropical passerines, which may respond opportunistically to the stimulus of a potential food item. -

Divergence in Nest Placement and Parental Care of Neotropical Foliage‐Gleaners and Treehunters (Furnariidae: Philydorini)

J. Field Ornithol. 88(4):336–348, 2017 DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12227 Divergence in nest placement and parental care of Neotropical foliage-gleaners and treehunters (Furnariidae: Philydorini) Kristina L. Cockle,1,2,3,4 and Alejandro Bodrati2 1Instituto de Bio y Geociencias del NOA (IBIGEO-CONICET-UNSa), 9 de julio 14, Rosario de Lerma, Salta 4405, Argentina 2Proyecto Selva de Pino Parana, Velez Sarsfield y San Jurjo SN, San Pedro, Misiones 3352, Argentina 3Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, University of British Columbia, 2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada Received 25 July 2017; accepted 23 September 2017 ABSTRACT. The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) are an adaptive radiation of suboscines renowned for the diversity of their nests. Like most altricial insectivores, they generally exhibit biparental care. One tribe, Philydorini, includes 46 species thought to nest in either underground burrows or tree cavities, nest types traditionally treated as equivalent in phylogenetic studies. Their parental care systems are poorly known, but could help illuminate how uniparental care – typically associated with frugivory – can arise in insectivores. We examined the extent to which nest placement, parental care, and associated reproductive traits map onto two major clades of Philydorini identified by genetic hypotheses. We review published literature and present new information from the Atlantic Forest of Argentina, including the first nest descriptions for Ochre-breasted Foliage-gleaners (Anabacerthia lichtensteini) and Sharp-billed Treehunters (Heliobletus contaminatus). In the Automolus-Thripadectes-Clibanornis clade (including Philydor rufum), 134 of 138 reported nests were in underground burrows. In the Syndactyla-Anabacerthia-Anabazenops clade (including Heliobletus, Philydor atricapillus, and Philydor erythrocercum), 44 of 48 nests were in tree cavities. -

A New Species of Cichlocolaptes Reichenbach 1853 (Furnariidae), the ‘Gritador-Do-Nordeste’, an Undescribed Trace of the Fading Bird Life of Northeastern Brazil

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 22(2), 75-94 ARTICLE June 2014 A new species of Cichlocolaptes Reichenbach 1853 (Furnariidae), the ‘gritador-do-nordeste’, an undescribed trace of the fading bird life of northeastern Brazil Juan Mazar Barnett1 and Dante Renato Corrêa Buzzetti2,3 1 Deceased. 2 Centro de Estudos Ornitológicos. Rua Álvaro Rodrigues 139, sala 4, CEP 04582-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 23 September 2013. Accepted on 21 May 2014. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5BE6C9E6-0E54-497E-84B8-90766A7A5A54, June 2014 ABSTRACT: A new species of treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti sp. nov., is described from a specimen that for many years had been confused with Philydor novaesi. The morphology of this specimen, collected in 1986 at Pedra Branca, Murici, Alagoas, at 550 m elevation (currently the Murici Ecological Station), suggests its allocation in the genus Cichlocolaptes. The new species differs from P. novaesi by its considerably larger size, heavier body-mass, darker and more uniform forehead and crown, absence of buffy periocular- feathers, and a pale orange-rufous tail that contrasts with the rump and the rest of the dorsal plumage. It also has a flat-crowned appearance and a larger, deeper-based, and generally stouter bill. Behavioral specialization on bromeliads and vocal repertoire also suggest that the new species belongs in the genus Cichlocolaptes. The song of this species is markedly different from that of P. novaesi, and it closely matches that of Cichlocolaptes leucophrus. The new species is endemic to the ‘Pernambuco Center’ of endemism, where it inhabits dense, humid forests in hilly terrain. -

Taxonomic Round-Up

Cotinga 25 Taxonomic Round-up Yet another new species from paraensis (in east Amazonian perhaps leading to further Peruvian white-sand forests...! Brazil). substantial refinements in our The remarkable white-sand • Whitney, B. M. & Alvarez Alonso, knowledge as it currently stands. (;varillal) forests of the J. (2005) A new species of • Maurício, G. N. (2005) Taxonomy Allpahuayo-Mishana National gnatcatcher from white-sand of southern populations in the Reserve, just west of Iquitos, Peru, forests of northern Amazonian Scytalopus speluncae group, have already yielded a handful of Peru with revision of the with description of a new species new species in recent years, Polioptila guianensis complex. and remarks on the systematics including a Zimmerius tyrannulet Wilson Bull. 117: 113-127. and biogeography of the complex (Cotinga 17: 11) and a Percnostola (Passeriformes: Rhinocryptidae). antbird (Cotinga 18: 15), and now Some insights into the Ararajuba 13: 7-28. Polioptila clementsi. To date, the taxonomy of Atlantic Forest new gnatcatcher is known only Scytalopus And another new species of from the recently created reserve, Whilst workers have appreciated Scytalopus from the Colombian and is rare even there (we have for over two decades the A ndes already remarked on its imperiled complexity of Scytalopus Scytalopus stilesi (named for the conservation status: see Cotinga populations in the Andean chain, many contributions to Colombian 18: 11-12). Indeed, the authors of it is only more recently that those and Neotropical ornithology of the type description recommend working in the Atlantic Forest Gary Stiles) is endemic to the that P. clementsi be categorised as have begun to appreciate the central Colombian Andes in the Critically Endangered, as suitable taxonomic problems inherent to dptos. -

South East Brazil, 18Th – 27Th January 2018, by Martin Wootton

South East Brazil 18th – 27th January 2018 Grey-winged Cotinga (AF), Pico da Caledonia – rare, range-restricted, difficult to see, Bird of the Trip Introduction This report covers a short trip to South East Brazil staying at Itororó Eco-lodge managed & owned by Rainer Dungs. Andy Foster of Serra Dos Tucanos guided the small group. Itinerary Thursday 18th January • Nightmare of a travel day with the flight leaving Manchester 30 mins late and then only able to land in Amsterdam at the second attempt due to high winds. Quick sprint (stagger!) across Schiphol airport to get onto the Rio flight which then parked on the tarmac for 2 hours due to the winds. Another roller-coaster ride across a turbulent North Atlantic and we finally arrived in Rio De Janeiro two hours late. Eventually managed to get the free shuttle to the Linx Hotel adjacent to airport Friday 19th January • Collected from the Linx by our very punctual driver (this was to be a theme) and 2.5hour transfer to Itororo Lodge through surprisingly light traffic. Birded the White Trail in the afternoon. Saturday 20th January • All day in Duas Barras & Sumidouro area. Luggage arrived. Sunday 21st January • All day at REGUA (Reserva Ecologica de Guapiacu) – wetlands and surrounding lowland forest. Andy was ill so guided by the very capable REGUA guide Adelei. Short visit late pm to Waldanoor Trail for Frilled Coquette & then return to lodge Monday 22nd January • All day around lodge – Blue Trail (am) & White Trail (pm) Tuesday 23rd January • Early start (& finish) at Pico da Caledonia. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

T H E C 0 N D 0 R r : : ,‘ “; i‘ . .. \ :i A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY ,I : Volume 99 Number 2 ’ I _ pg$$ij ,- The Condor 99~253-270 D The Cooper Ornithological Society 1997 ON THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEST BUILDING BY PASSERINE BIRDS’ NICHOLAS E. COLLIAS Departmentof Biology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1606 Abstract. The object of this review is to relate nest-buildingbehavior to the origin and early evolution of passerinebirds (Order Passeriformes).I present evidence for the hypoth- esis that the combinationof small body size and the ability to place a constructednest where the bird chooses,helped make possiblea vast amountof adaptiveradiation. A great diversity of potential habitats especially accessibleto small birds was created in the late Tertiary by global climatic changes and by the continuing great evolutionary expansion of flowering plants and insects.Cavity or hole nests(in ground or tree), open-cupnests (outside of holes), and domed nests (with a constructedroof) were all present very early in evolution of the Passeriformes,as indicated by the presenceof all three of these basic nest types among the most primitive families of living passerinebirds. Secondary specializationsof these basic nest types are illustratedin the largest and most successfulfamilies of suboscinebirds. Nest site and nest form and structureoften help characterizethe genus, as is exemplified in the suboscinesby the ovenbirds(Furnariidae), a large family that builds among the most diverse nests of any family of birds. The domed nest is much more common among passerinesthan in non-passerines,and it is especially frequent among the very smallestpasserine birds the world over. -

Furnariinae Species Tree, Part 1

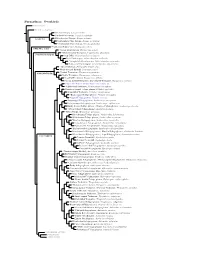

Furnariinae: Ovenbirds Sclerurinae Dendrocolaptinae Streaked Xenops, Xenops rutilans Slender-billed Xenops, Xenops tenuirostris Xenops minutus XENOPINI White-throated Xenops, Northwestern Plain Xenops, Xenops mexicanus !Southeastern Plain Xenops, Xenops genibarbus !Point-tailed Palmcreeper, Berlepschia rikeri BERLEPSCHIINI ! Rufous-tailed Xenops, Microxenops milleri !White-throated Treerunner, Pygarrhichas albogularis PYGARRHICHADINI Crag Chilia, Ochetorhynchus melanurus Rock Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus andaecola !Straight-billed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus ruficaudus Band-tailed Earthcreeper, Ochetorhynchus phoenicurus !Spotted Barbtail, Premnoplex brunnescens White-throated Barbtail, Premnoplex tatei !Pearled Treerunner, Margarornis squamiger MARGARORNINI Ruddy Treerunner, Margarornis rubiginosus Beautiful Treerunner, Margarornis bellulus Fulvous-dotted Treerunner / Star-chested Treerunner, Margarornis stellatus Cryptic Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti !Pale-browed Treehunter, Cichlocolaptes leucophrus Cinnamon-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor pyrrhodes Sharp-billed Treehunter, Philydor contaminatus !Black-capped Foliage-gleaner, Philydor atricapillus Alagoas Foliage-gleaner, Philydor novaesi Slaty-winged Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscipennis Rufous-rumped Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops erythrocercus Dusky-cheeked Foliage-gleaner / Bamboo Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops dorsalis !White-collared Foliage-gleaner, Anabazenops fuscus !Great Xenops, Megaxenops parnaguae Ochre-breasted Foliage-gleaner, Anabacerthia lichtensteini White-browed -

DRAFT Fifth Edition of the Global Biodiversity Outlook (GBO-5)

DRAFT FOR REVIEW – NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, REPRODUCTION OR QUOTATION 1 2 This is a draft for review. The data, material and messages contained in this draft may not be republished, 3 displayed, distributed, or transmitted in any manner, nor may the material, or portion thereof, be copied or 4 posted on any other website or network or otherwise distributed, quoted or cited.The report will be revised in 5 light of review comments, and also updated to take into account additional material from the sixth national 6 reports. The figures will be redrawn and simplified. 7 8 DRAFT 9 Fifth edition of the Global Biodiversity Outlook (GBO-5) 10 11 Table of contents 12 SUMMARY FOR POLICY MAKERS……………………………………………………………..…...…..3 13 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………..…...…..9 14 Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 15 Background and context .................................................................................................................................. 10 16 Climate change and the Sustainable Development Goals ............................................................................... 13 17 IPBES and additional sources.......................................................................................................................... 15 18 2. BIODIVERSITY IN 2020 ........................................................................................................................ 17 19