The Wolfe Tone Society 1963-1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare 2000 ‘Former Republicans have been bought off with palliatives’ Cathleen Knowles McGuirk, Vice President Republican Sinn Féin delivered the oration at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish Republicanism, on Sunday, June 11 in Bodenstown cemetery, outside Sallins, Co Kildare. The large crowd, led by a colour party carrying the National Flag and contingents of Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna Éireann, as well as the General Tom Maguire Flute Band from Belfast marched the three miles from Sallins Village to the grave of Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown. Contingents from all over Ireland as well as visitors from Britain and the United States took part in the march, which was marshalled by Seán Ó Sé, Dublin. At the graveside of Wolfe Tone the proceedings were chaired by Seán Mac Oscair, Fermanagh, Ard Chomhairle, Republican Sinn Féin who said he was delighted to see the large number of young people from all over Ireland in attendance this year. The ceremony was also addressed by Peig Galligan on behalf of the National Graves Association, who care for Ireland’s patriot graves. Róisín Hayden read a message from Republican Sinn Féin Patron, George Harrison, New York. Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare “A chairde, a comrádaithe agus a Phoblactánaigh, tá an-bhród orm agus tá sé d’onóir orm a bheith anseo inniu ag uaigh Thiobóid Wolfe Tone, Athair an Phoblachtachais in Éirinn. Fellow Republicans, once more we gather here in Bodenstown churchyard at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the greatest of the Republican leaders of the 18th century, the most visionary Irishman of his day, and regarded as the “Father of Irish Republicanism”. -

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

Irish Political Review, January, 2011

Of Morality & Corruption Ireland & Israel Another PD Budget! Brendan Clifford Philip O'Connor Labour Comment page 16 page 23 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW January 2011 Vol.26, No.1 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.25 No.1 ISSN 954-5891 Economic Mindgames Irish Budget 2011 To Default or Not to Default? that is the question facing the Irish democracy at present. In normal circumstances this would be Should Ireland become the first Euro-zone country to renege on its debts? The bank debt considered an awful budget. But the cir- in question has largely been incurred by private institutions of the capitalist system, cumstances are not normal. Our current which. made plenty money for themselves when times were good—which adds a budget deficit has ballooned to 11.6% of piquancy to the choice ahead. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) excluding As Irish Congress of Trade Unions General Secretary David Begg has pointed out, the bank debt (over 30% when the once-off Banks have been reckless. The net foreign debt of the Irish banking sector was 10% of bank recapitalisation is taken into account). Gross Domestic Product in 2003. By 2008 it had risen to 60%. And he adds: "They lied Our State debt to GDP is set to increase to about their exposure" (Irish Times, 13.12.10). just over 100% in the coming years. A few When the world financial crisis sapped investor confidence, and cut off the supply of years ago our State debt was one of the funds to banks across the world, the Irish banks threatened to become insolvent as private lowest, but now it is one of the highest, institutions. -

1798) the Pockets of Our Great-Coats Full of Barley (No Kitchens on the Run, No Striking Camp) We Moved Quick and Sudden in Our Own Country

R..6~t6M FOR.. nt6 tR..tSH- R..6lS6LS (Wexford, 1798) The pockets of our great-coats full of barley (No kitchens on the run, no striking camp) We moved quick and sudden in our own country. The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp. A people, hardly marching - on the hike - We found new tactics happening each day: Horsemen and horse fell to the twelve foot pike, 1 We'd stampede cattle into infantry, Retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown Until, on Vinegar Hill, the fatal conclave: Twenty thousand died; shaking scythes at cannon. The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave. They buried us without shroud or coffin And in August barley grew up out of the grave. ---- - Seamus Heaney our prouvt repubLLctt"" trttvtLtLo"" Bodenstown is a very special place for Irish republicans. We gather here every year to honour Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen and to rededicate ourselves to the principles they espoused. We remember that it was the actions of the 1916 leaders and their comrades, inspired by such patriot revolutionaries as Tone and Emmett, that lit the flame that eventually destroyed the British Empire and reawakened the republicanism of the Irish people. The first article of the constitution of the Society of United Irishmen stated as its purpose, the 'forwarding a brotherhood of affection, a communion of rights, and an union of power among Irishmen of every religious persuasion'. James Connolly said of Wolfe Tone that he united "the hopes of the new revolutionary faith and the ancient aspirations of an oppressed people". -

The Irish Diaspora in Britain & America

Reflections on 1969 Lived Experiences & Living history (Discussion 6) The Irish Diaspora in Britain & America: Benign or Malign Forces? compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 123 PAMPHLETS 1 Published January 2020 by Island Publications 132 Serpentine Road, Newtownabbey BT36 7JQ © Michael Hall 2020 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications The Fellowship of Messines Association gratefully acknowledge the assistance they have received from their supporting organisations Printed by Regency Press, Belfast 2 Introduction The Fellowship of Messines Association was formed in May 2002 by a diverse group of individuals from Loyalist, Republican and other backgrounds, united in their realisation of the need to confront sectarianism in our society as a necessary means of realistic peace-building. The project also engages young people and new citizens on themes of citizenship and cultural and political identity. Among the different programmes initiated by the Messines Project was a series of discussions entitled Reflections on 1969: Lived Experiences & Living History. These discussions were viewed as an opportunity for people to engage positively and constructively with each other in assisting the long overdue and necessary process of separating actual history from some of the myths that have proliferated in communities over the years. It was felt important that current and future generations should hear, and have access to, the testimonies and the reflections of former protagonists while these opportunities still exist. Access to such evidence would hopefully enable younger generations to evaluate for themselves the factuality of events, as opposed to some of the folklore that passes for history in contemporary society. -

1/- D E M O C R

MOVING FOR 1/- A UNITED DEMOCRAT No. 289 SEPTEMBER 1968 IRELAND APPEAL TO MANY ORGANISATIONS LONDON IRISH MARCH People of six counties at end of tether FOR CIVIL RIGHTS ^J NLESS something is done soon to end the injustices Which exist in British occupied Ireland there is going to be an explosion there. Cheers from onlookers The people are getting to the This is the message of the great in Camden have undertaken to end of their tether, with end- meeting and parade from Coal- join with the Association in poster island to Dungannon on Saturday, less unemployment, low wages, parades. They see the struggle for August 24th, 1968, a date to be QNLOOKERS the pavements when members of the shortage of housing, all backed on cheered remembered. Irish independence as on a par ^ Connolly Association, Clann na hEireann and the Republican up by religious discrimination, with the struggle against the dis- Party walked from Manette Street, Charing Cross Road, to Marble gerrymandering and police dic- This is the message that has graceful war in Vietnam. Arch to demand the introduction of normal democracy into the tatorship. come from Ireland to the Connolly six counties of north east Ireland- Association in London, and to which the Association intends to CONFERENCE The parade took place on Sun- react as its duty is. In order to get the new campaign day, July 28th, and was followed under way Central London Con- by a meeting in Hyde Park, at which the speakers were Sean Red- INITIATIVE nolly Association is calling a con- ference on September 11th of mond, General Secretary of the Central London Branch of the Connolly Association; Desmond interested organisations in the two Association is to take the initia- Greaves; Robert Heatley and Jack central boroughs of Camden and tive in a new campaign which it Henry, the building workers' ste- Islington. -

DEMYSTIFYING FEMININE IRELAND DURING the REBELLION of 1798 Cecilia Barnard

DEMYSTIFYING FEMININE IRELAND DURING THE REBELLION OF 1798 Cecilia Barnard Although the role assigned to women by Irish historians during the era of the United Irishmen is one of background involvement and passivity, Mary Ann McCracken and Elizabeth Richards provide important case studies to the contrary. Directly opposing not just history but contemporary propaganda, Elizabeth and Mary Ann stood firmly for their beliefs and now provide important insights into the rebellions. Instead of being a passive Hibernia or a ragged Granu, the women of Ireland in the 1790s had experiences and emotions that ranged from distrust and terror to active involvement in the movement. Irish women were part and parcel to the events in the rebellion, and that including them as active participants in the story of the rebellion provides an insight that the historical context will continue to miss if their participation remains in the background rather than the forefront. Introduction The prescribed role of Irish women during the Irish rebellions of 1798 was as victims of exploitation, both in propaganda and in life.1 Even though the Irish Unionist movement promoted itself as an egalitarian movement dedicated to the common good, this common good did not include women. Women were not seen as equal partners in the movement. The United Irishmen gave no significant consideration of the extension of the franchise to its female members at any time in its activism, which historians point to as modern evidence of their entrenched gender inequality.2 It’s doubtful that women were only the passive participants described by historians and Unionist propaganda during the Unionist movement and the rebellions as a whole, but their historical contributions have been largely neglected by the larger scholarship on Irish history.3 The aim of this paper is to analyze the differences between women in Unionist legend at the time and the recorded lived experiences of women from the 1790s, specifically women who documented life in their own words in the late 1790s. -

Irish Patriot: Wolfe Tone

ENGLAND TAKES OVER 0. ENGLAND TAKES OVER - Story Preface 1. WHO WAS WOLFE TONE? 2. ENGLAND TAKES OVER 3. IRISH CATHOLICS DENIED THE VOTE 4. THE SOCIETY OF UNITED IRISHMEN 5. THE PLAN FOR IRISH FREEDOM 6. STEP ONE FAILS 7. STRIKE TWO 8. WOLFE TONE IS BETRAYED 9. CORNWALLIS GETS HIS REVENGE 10. A TRIAL WITHOUT JUSTICE 11. NO HOPE 12. ATTEMPTS TO SAVE TONE 13. A FINAL ACT OF DEFIANCE 14. IRELAND DECLARES FREEDOM 15. THE EFFECTS TODAY, ANGELA'S ASHES 16. MORE COOL LINKS Young Wolfe's Ireland had long been dominated by England, but things did not start out that way. Before the reign of Henry VIII, English people lived in Ireland (they had since the 12th century) but did not control Irish affairs. Life, however, changed dramatically for the Irish people when Henry VIII was king (1509-1547). He wanted to rule Ireland. In order to actualize his objective, Henry VIII sent English Protestants to Ireland. Their mission was to "colonize" an already established, largely Catholic country.Elizabeth I continued her father's efforts with a more audacious plan: establish English plantations throughout Ireland. She achieved even more dramatic results than her father. Declaring that all newly established plantations belonged to England, Elizabeth forced the Irish people to rent the very land they had once owned. This effort to "colonize" Ireland was very successful, especially in the areas around Dublin and in the province of Ulster. The town of "Derry" became "Londonderry." The Irish Parliament, which had so effectively managed the daily affairs of Ireland, became "Irish" in name only. -

EXPLORING the 1798 REBELLION1795 1800 EXPLORING the IRISH HISTORY 10 1798 REBELLION – the Impact of the Physical Force Tradition in Irish Politics

1775 1780 1785 1790 EXPLORING THE 1798 REBELLION1795 1800 EXPLORING THE IRISH HISTORY 10 1798 REBELLION – The Impact of the Physical Force Tradition in Irish Politics Use the information in this page to create a mind map of the causes of the 1798 Rebellion. 2 Catholic and Presbyterian Discontent 1 The Power of the The Protestant Ascendancy used the 3 Protestant Ascendancy Poverty in the Countryside penal laws to maintain its power. These At the end of the 18th were laws that discriminated against The majority of people in Ireland century, Ireland was Catholics and Presbyterians. lived in the countryside. Most of ruled by a parliament the people were tenant farmers Catholics, who formed 75 per cent of the in Dublin that was and landless labourers. The population, lived all over Ireland, but under the control population of Ireland doubled in Presbyterians, who formed 10 per cent, of Great Britain. The the 18th century, so many farms lived mainly in Ulster. Irish parliament was were subdivided. Many people controlled by the After 1770, some of the penal laws were were very badly off. abolished (repealed). However, Catholics Protestant Ascendancy, Agrarian (rural) societies, such and Presbyterians still protested about that is, by members of as the Whiteboys, were formed the remaining laws. They also had to the Church of Ireland (or to protest against high rents and pay tithes (one-tenth of their crops) to Anglican Church). Even tithes. though they made up support the Anglican clergy. only 15 per cent of the population, they owned most of the land of 4 Ireland, which they got The Causes of the The Influence of the American and during the plantations. -

Accounting and Discounting for the International Contacts of the Provisional Irish Republican Army by Michael Mckinley

Conflict Quarterly Of "Alien Influences": Accounting and Discounting for the International Contacts of the Provisional Irish Republican Army by Michael McKinley NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL CONTACTS In a world where nation states are unanimous in their disavowal of terrorism — even if they are incapable of unanimously agreeing on a defini tion of what it is they are disavowing — and in a Western Europe which regards separatist and irredentist claims as anathema, mere is a natural ten dency for those who are so excluded to make common cause where they might Disparate as these groups are, they really have only themselves to meet as equals; though they might wish to be nation states or represent nation states in the fullness of time, they exist until then as interlopers in the relations between states: seldom invited and then almost always disappointed by their reception. It is a world with which the Provisional Irish Republican Army and its more political expression, Sinn Fein, are entirely familiar and also one in which, given their history, political complexion, strategy and objectives, it would be extraordinarily strange for them not to have a wide range of inter national contacts. But potent as the reflex of commonality by exclusion is, it does not completely determine these linkages because to argue this is to argue on the basis of default rather than purpose. For the Provisionals there is a utility not only of making such contacts but also in formalizing them where possible within the movements' organizational structure. Thus, in 1976 the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis moved to establish, under the directorship of Risteard Behal, a Foreign Affairs Bureau, with Behal as its first "sort of roving Euro pean ambassador . -

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954–69

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES ON REPUBLICANISM AND SOCIALISM IN CORK CITY, 1954–69 By Jim Lane Note: What follows deals almost entirely with internal divisions within Cork republicanism and is not meant as a comprehensive outline of republican and left-wing activities in the city during the period covered. Moreover, these notes were put together following specific queries from historical researchers and, hence, the focus at times is on matters that they raised. 1954 In 1954, at the age of 16 years, I joined the following branches of the Republican Movement: Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Army and the Cork Volunteers’Pipe Band. The most immediate influence on my joining was the discovery that fellow Corkmen were being given the opportunity of engag- ing with British Forces in an effort to drive them out of occupied Ireland. This awareness developed when three Cork IRA volunteers were arrested in the North following a failed raid on a British mil- itary barracks; their arrest and imprisonment for 10 years was not a deterrent in any way. My think- ing on armed struggle at that time was informed by much reading on the events of the Tan and Civil Wars. I had been influenced also, a few years earlier, by the campaigning of the Anti-Partition League. Once in the IRA, our initial training was a three-month republican educational course, which was given by Tomas Óg MacCurtain, son of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, who was murdered by British forces at his home in 1920. This course was followed by arms and explosives training. -

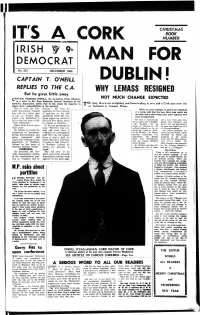

Irish Democrat." He Regards As Tripartite

CHRISTMAS BOOK ITS A CORK NUMBER IRISH 9 DEMOCRAT MAN FOR No. 267 DECEMB ER 1966 CAPTAIN T. O'NEILL DUBLIN! REPLIES TO THE C.A. WHY LEMASS RESIGNED But- he gives little away £APTAIN TERENCE O'NEILL, the six-county Prime Minister, NOT MUCH CHANGE EXPECTED in a letter to Mr. Sean Redmond, General Secretary of the Connolly Association, denies that he lias urged the majority to 'HE long drawn-out in-fighting and horse-trading is over and a Cork man now sits ignore their responsibilities to the minority. as Taoiseach in Leinster House. This is what the Con- genious." He rests his While no great changes of policy are expected, nolly Association charged argument for the retention it is being said that the new Cork man could not him with in a letter sent of partition on the 1925 do much worse than those from other counties who to him on October 26th, agreement which Mr. Cos- have preceded him. which was published in grave signed on behalf of full in the last issue of the the Irish Free State, which The team is substantially and a half, "Posts and Tele- Mr. Lemass's, but re-shuffled. "Irish Democrat." he regards as tripartite. graphs and Transport and Mr. Haughey will no Power," but this may shortly Apart from this he gives In his last paragraph he longer be plagued by the be made one under the title little away. says: "Between your out- militant farmers, as he re- of "Communications." He refuses to accept the look and mine there is places Mr.