Increase Your Font Size

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

What Resolution Should Your Images Be?

What Resolution Should Your Images Be? The best way to determine the optimum resolution is to think about the final use of your images. For publication you’ll need the highest resolution, for desktop printing lower, and for web or classroom use, lower still. The following table is a general guide; detailed explanations follow. Use Pixel Size Resolution Preferred Approx. File File Format Size Projected in class About 1024 pixels wide 102 DPI JPEG 300–600 K for a horizontal image; or 768 pixels high for a vertical one Web site About 400–600 pixels 72 DPI JPEG 20–200 K wide for a large image; 100–200 for a thumbnail image Printed in a book Multiply intended print 300 DPI EPS or TIFF 6–10 MB or art magazine size by resolution; e.g. an image to be printed as 6” W x 4” H would be 1800 x 1200 pixels. Printed on a Multiply intended print 200 DPI EPS or TIFF 2-3 MB laserwriter size by resolution; e.g. an image to be printed as 6” W x 4” H would be 1200 x 800 pixels. Digital Camera Photos Digital cameras have a range of preset resolutions which vary from camera to camera. Designation Resolution Max. Image size at Printable size on 300 DPI a color printer 4 Megapixels 2272 x 1704 pixels 7.5” x 5.7” 12” x 9” 3 Megapixels 2048 x 1536 pixels 6.8” x 5” 11” x 8.5” 2 Megapixels 1600 x 1200 pixels 5.3” x 4” 6” x 4” 1 Megapixel 1024 x 768 pixels 3.5” x 2.5” 5” x 3 If you can, you generally want to shoot larger than you need, then sharpen the image and reduce its size in Photoshop. -

Basic Styles of Lettering for Monuments and Markers.Indd

BASIC STYLES OF LETTERING FOR MONUMENTS AND MARKERS Monument Builders of North America, Inc. AA GuideGuide ToTo TheThe SelectionSelection ofof LETTERINGLETTERING From primitive times, man has sought to crude or garish or awkward letters, but in communicate with his fellow men through letters of harmonized alphabets which have symbols and graphics which conveyed dignity, balance and legibility. At the same meaning. Slowly he evolved signs and time, they are letters which are designed to hieroglyphics which became the visual engrave or incise cleanly and clearly into expression of his language. monumental stone, and to resist change or obliteration through year after year of Ultimately, this process evolved into the exposure. writing and the alphabets of the various tongues and civilizations. The early scribes The purpose of this book is to illustrate the and artists refi ned these alphabets, and the basic styles or types of alphabets which have development of printing led to the design been proved in memorial art, and which are of alphabets of related character and ready both appropriate and practical in the lettering readability. of monuments and markers. Memorial art--one of the oldest of the arts- Lettering or engraving of family memorials -was among the fi rst to use symbols and or individual markers is done today with “letters” to inscribe lasting records and history superb fi delity through the use of lasers or the into stone. The sculptors and carvers of each sandblast process, which employs a powerful generation infl uenced the form of letters and stream or jet of abrasive “sand” to cut into the numerals and used them to add both meaning granite or marble. -

Printing Terms

Printing Terms Bitmap - Also called a BMP or a raster image. A digital image that is pixel based and resolution dependent. Bit-mapped images loose sharpness and clarity when reduced or enlarged. These files are specified as a number of pixels wide by the number of pixels high. The number of bits per pixel determines the number of shades of grey or colors it can represent. Bitmaps come in many file formats, a few are GIF, JPEG, TIFF, BMP, PICT, and PSD. These types of images are created in paint programs, by scanning and by digital cameras. Bit- mapped files can also be placed or imported into a vector based file, but they remain raster images. For the promotional products industry, bit-mapped or raster images are not usually the preferred type of art for vendors to work with as they are more difficult to make adjustments such as re-sizing. CMYK - A color model where all the colors are made up of a combination of four process colors. CMYK is an abbreviation for cyan (a blue color), magenta (a red color), yellow and key (black). Color Separations - The process of separating the areas of a piece of art to be printed into its component spot or process ink colors. Each color to be printed must have its own printing plate. For example, if a piece of art was to be printed in 3 spot colors, such as PMS 185C Red, PMS 288C Blue and Black, there would be 3 plates. Each of the 3 plates would contain only the elements to be printed in a specific color. -

Guide to Digital Art Specifications

Guide to Digital Art Specifications Version 12.05.11 Image File Types Digital image formats for both Mac and PC platforms are accepted. Preferred file types: These file types work best and typically encounter few problems. tif (TIFF) jpg (JPEG) psd (Adobe Photoshop document) eps (Encapsulated PostScript) ai (Adobe Illustrator) pdf (Portable Document Format) Accepted file types: These file types are acceptable, although application versions and operating systems can introduce problems. A hardcopy, for cross-referencing, will ensure a more accurate outcome. doc, docx (Word) xls, xlsx (Excel) ppt, pptx (PowerPoint) fh (Freehand) cdr (Corel Draw) cvs (Canvas) Image sizing specifications should be discussed with the Editorial Office prior to digital file submission. Digital images should be submitted in the final size desired. White space around the image should be removed. Image Resolution The minimum acceptable resolution is 200 dpi at the desired final size in the paged article. To ensure the highest-quality published image, follow these optimum resolutions: • Line = 1200 dpi. Contains only black and white; no shades of gray. These images are typically ink drawings or charts. Other common terms used are monochrome or 1-bit. • Grayscale or Color = 300 dpi. Contains no text. A photograph or a painting is an example of this type of image. • Combination = 600 dpi. Grayscale or color image combined with a line image. An example is a photograph with letter labels, arrows, or text added outside the image area. Anytime a picture is combined with type outside the image area, the resolution must be high enough to maintain smooth, readable text. -

Surviving the TEX Font Encoding Mess Understanding The

Surviving the TEX font encoding mess Understanding the world of TEX fonts and mastering the basics of fontinst Ulrik Vieth Taco Hoekwater · EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg E · FAMOUS QUOTE: English is useful because it is a mess. Since English is a mess, it maps well onto the problem space, which is also a mess, which we call reality. Similary, Perl was designed to be a mess, though in the nicests of all possible ways. | LARRY WALL COROLLARY: TEX fonts are mess, as they are a product of reality. Similary, fontinst is a mess, not necessarily by design, but because it has to cope with the mess we call reality. Contents I Overview of TEX font technology II Installation TEX fonts with fontinst III Overview of math fonts EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg 24. September 1999 3 E · · I Overview of TEX font technology What is a font? What is a virtual font? • Font file formats and conversion utilities • Font attributes and classifications • Font selection schemes • Font naming schemes • Font encodings • What’s in a standard font? What’s in an expert font? • Font installation considerations • Why the need for reencoding? • Which raw font encoding to use? • What’s needed to set up fonts for use with T X? • E EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg 24. September 1999 4 E · · What is a font? in technical terms: • – fonts have many different representations depending on the point of view – TEX typesetter: fonts metrics (TFM) and nothing else – DVI driver: virtual fonts (VF), bitmaps fonts(PK), outline fonts (PFA/PFB or TTF) – PostScript: Type 1 (outlines), Type 3 (anything), Type 42 fonts (embedded TTF) in general terms: • – fonts are collections of glyphs (characters, symbols) of a particular design – fonts are organized into families, series and individual shapes – glyphs may be accessed either by character code or by symbolic names – encoding of glyphs may be fixed or controllable by encoding vectors font information consists of: • – metric information (glyph metrics and global parameters) – some representation of glyph shapes (bitmaps or outlines) EuroT X ’99 Heidelberg 24. -

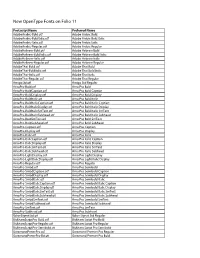

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Patrick Reagh Printers Note: the Number Following the Name Indicates the Monotype Series

Monotype typefaces available for fonts and composition at Patrick Reagh Printers note: the number following the name indicates the Monotype series. An e or an a after the number indicates either English- or American-manufactured matrices. R-roman / I-italic / SC-small caps / B-boldface lc-large composition* Antique 26a R 8 10 12 Baskerville 353a R/I/SC 7 8 10 11 12 Bembo 270e R/I/SC 8 10 11 12 13 14 (16 & 18 lc R/I) Narrow Bembo Italic 194e 10 12 13 (16 lc) Bodoni Medium 375a R/I/SC 8 10 12 Bodoni Book 875a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Bookman 98a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Bulmer 462a R/I/SC 6 8 9 10 12 (18 lc R) Centaur 252a (16 lc roman only) Cochin 61a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Deepdene 315a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Ehrhardt 453e R/I/SC 10 12 14 Fournier 185e R/I/SC 10 12 13 Franklin Gothic 107a R 6 8 10 12 Futura Light 606a R/I 6 8 10 12 Futura Medium /Extra Bold 605a & 603a R 6 8 10 12 Garamont 248a R/I/SC 8 10 12 Garamond Bold 548a R/I 6 8 10 12 Gill Sans 262e R/I/B 6 7 8 10 12 Goudy Bold 294a R/I 8 10 12 Goudy Modern 249e R/I/SC 8 10 11 12 Goudy Old Style 394a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Janson 401a R/I/SC 8 9 10 11 12 (14 & 18 lc R/I) Jenson Old Style 58a R 8 10 12 Sans Serif 329a (Kabel) R/B 8 10 12 Sans Serif Light/Bold 329a & 330a R 8 10 12 Univers Light 45e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 Univers Medium 55e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 Univers Bold 65e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 Univers Extra Bold 75e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 *Large composition can only be composed in roman or italic separately 1 Monotype display typefaces available for fonts at Patrick Reagh Printers note: the letter d following the size on English matrices indicates Didot which is the European standard for type sizing and is generally a point or two larger than the American point system. -

Type Design for Typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva

Type design for typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MA in Typeface Design Department of Typography & Graphic Communication University of Reading, United Kingdom September 2015 The word utopia is the most convenient way to sell off what one has not the will, ability, or courage to do. A dream seems like a dream until one begin to work on it. Only then it becomes a goal, which is something infinitely bigger.1 -- Adriano Olivetti. 1 Original text: ‘Il termine utopia è la maniera più comoda per liquidare quello che non si ha voglia, capacità, o coraggio di fare. Un sogno sembra un sogno fino a quando non si comincia da qualche parte, solo allora diventa un proposito, cio è qualcosa di infinitamente più grande.’ Source: fondazioneadrianolivetti.it. -- Abstract The history of the typewriter has been covered by writers and researchers. However, the interest shown in the origin of the machine has not revealed a further interest in one of the true reasons of its existence, the printed letters. The following pages try to bring some light on this part of the history of type design, typewriter typefaces. The research focused on a particular company, Olivetti, one of the most important typewriter manufacturers. The first two sections describe the context for the main topic. These introductory pages explain briefly the history of the typewriter and highlight the particular facts that led Olivetti on its way to success. The next section, ‘Typewriters and text composition’, creates a link between the historical background and the machine. -

Bash . . Notes, Version

2.2 Quoting and literals 4. ${#var} returns length of the string. Inside single quotes '' nothing is interpreted: 5. ${var:offset:length} skips first offset they preserve literal values of characters enclosed characters from var and truncates the output Bash 5.1.0 notes, version 0.2.209 within them. A single (strong) quote may not appear to given length. :length may be skipped. between single quotes, even when escaped, but it Negative values separated with extra space may appear between double (weak) quotes "". Remigiusz Suwalski are accepted. ey work quite similarly, with an exception that the 6. uses a default value, if shell expands any variables that appear within them ${var:-value} var August 19, 2021 is empty or unset. (pathname expansion, process substitution and word splitting are disabled, everything else works!). ${var:=value} does the same, but performs an assignment as well. Bash, a command line interface for interacting with It is a very important concept: without them Bash the operating system, was created in the 1980s. splits lines into words at whitespace characters – ${var:+value} uses an alternative value if 1 (Google) shell style guide tabs and spaces. See also: IFS variable and $'...' var isn’t empty or unset! and $"..." (both are Bash extensions, to be done). e following notes are meant to be summary of a 2.4.4 Command substitution style guide written by Paul Armstrong and too many Avoid backticks `code` at all cost! To execute commands in a subshell and then pass more to mention (revision 1.26). 2.3 Variables their stdout (but not stderr!), use $( commands) . -

The Impact of the Historical Development of Typography on Modern Classification of Typefaces

M. Tomiša et al. Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) UDC/UDK 655.26:003.2 THE IMPACT OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOGRAPHY ON MODERN CLASSIFICATION OF TYPEFACES Mario Tomiša, Damir Vusić, Marin Milković Original scientific paper One of the definitions of typography is that it is the art of arranging typefaces for a specific project and their arrangement in order to achieve a more effective communication. In order to choose the appropriate typeface, the user should be well-acquainted with visual or geometric features of typography, typographic rules and the historical development of typography. Additionally, every user is further assisted by a good quality and simple typeface classification. There are many different classifications of typefaces based on historical or visual criteria, as well as their combination. During the last thirty years, computers and digital technology have enabled brand new creative freedoms. As a result, there are thousands of fonts and dozens of applications for digitally creating typefaces. This paper suggests an innovative, simpler classification, which should correspond to the contemporary development of typography, the production of a vast number of new typefaces and the needs of today's users. Keywords: character, font, graphic design, historical development of typography, typeface, typeface classification, typography Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama Izvorni znanstveni članak Jedna je od definicija tipografije da je ona umjetnost odabira odgovarajućeg pisma za određeni projekt i njegova organizacija s ciljem ostvarenja što učinkovitije komunikacije. Da bi korisnik mogao odabrati pravo pismo za svoje potrebe treba prije svega dobro poznavati optičke ili geometrijske značajke tipografije, tipografska pravila i povijesni razvoj tipografije. -

P Font-Change Q UV 3

p font•change q UV Version 2015.2 Macros to Change Text & Math fonts in TEX 45 Beautiful Variants 3 Amit Raj Dhawan [email protected] September 2, 2015 This work had been released under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License on July 19, 2010. You are free to Share (to copy, distribute and transmit the work) and to Remix (to adapt the work) provided you follow the Attribution and Share Alike guidelines of the licence. For the full licence text, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode. 4 When I reach the destination, more than I realize that I have realized the goal, I am occupied with the reminiscences of the journey. It strikes to me again and again, ‘‘Isn’t the journey to the goal the real attainment of the goal?’’ In this way even if I miss goal, I still have attained goal. Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Usage .................................................................................. 1 Example ............................................................................... 3 AMS Symbols .......................................................................... 3 Available Weights ...................................................................... 5 Warning ............................................................................... 5 Charter ....................................................................................... 6 Utopia .......................................................................................