Towards a Uniform Nomenclature for Ground Squirrels: the Status of the Holarctic Chipmunks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory of Terrestrial Mammals in the Rincon Mountains Using Camera Traps

Inventory of Terrestrial Mammals in the Rincon Mountains Using Camera Traps Don E. Swann and Nic Perkins Saguaro National Park, Tucson, Arizona Abstract— The Sky Island region of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico is well-known for its diversity of mammals, including endemic species and species representing several different biogeo- graphic provinces. Camera trap studies have provided important insight into mammalian distribution and diversity in the Sky Islands in recent years, but few studies have attempted systematic inventories of one or more mountain ranges with a repeatable, randomized study design. We surveyed medium and large terrestrial mammals of the Rincon Mountains within Saguaro National Park, and compared the results with previous surveys of the Rincons. We sampled in random locations in four elevational strata from May 2011 through April 2012. We detected 23 native species of mammals and estimated species richness to be 24.8 species. We failed to detect four native species documented by other methods during 1999-2012, as well as five species (bighorn sheep, grizzly bear, jaguar, gray wolf, and North American porcupine) documented during 1900-1999 that may be extirpated from the Rincons. Advances in camera trap technology, as well an expanding use of this technology by educators and the public, suggest this method has the potential to be a cost-effective and reliable method for both inventory and long-term monitoring of terrestrial mammals of Sky Island region. Introduction using a randomized, repeatable study design that allows estimates to be made of measures such as native species richness (the number The Sky Island region of the southwestern United States and of native species that occur in an area). -

Program & Faculty Guide

Program & Faculty Guide UNLV School of Life Sciences UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, LAS VEGAS Contents From the Director ..................... 3 About UNLV .............................. 4 Programs .................................. 5 Facilities ................................... 7 Graduate Students ..................11 Postdoctoral Scholars ............13 Faculty Researchers .............. 15 UNLV School of Life Sciences From the Director The School of Life Sciences (SoLS) is one of the largest academic units on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) campus. It has 30 full-time faculty members, 10 adjunct and research faculty, more than 1,900 undergraduate majors, and approximately 55 graduate students. The school’s offices and laborato- ries are located in four buildings: Juanita Greer White Hall (WHI), the Science and Engineering Building (SEB), the White Hall Annex (WHA2), the Campus Lab Building (CLB). Research facilities on campus include centers for bioinformatics/biostatics with access to supercomputer facilities, confocal and biological imaging core with a new a high-speed laser-scanning microscope, genomics center, greenhouses, tissue culture facilities, environmental chambers and mod- ern animal care facilities. The faculty research and graduate programs are or- ganized into Bioinformatics, Cell & Molecular Biology, Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Integrative Physiology, School of Life Sciences Director Frank van Breukelen and Microbiology. SoLS faculty are recruited from some of the best research institutions and currently collaborate with the Nevada Institute of Personalized Medicine (NIPM), Lou Ruvo Center, Desert Research Institute (DRI), BLM, USGS, US National Park Service, and with faculty and researchers at many universities and government agencies throughout the nation and international institutions, providing ex- panded opportunities for our students. The faculty compete successfully for funding from BLM, DOE, DOI, FWS, NASA, NIH, NSF, USDA, USGS and other agencies. -

Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Management Plan

Badlands National Park – North Unit Environmental Assessment U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Badlands National Park, North Unit Pennington and Jackson Counties, South Dakota Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Management Plan Environmental Assessment August 2007 Badlands National Park – North Unit Environmental Assessment National Park Service Prairie Dog Management Plan U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Management Plan Environmental Assessment Badlands National Park, North Unit Pennington and Jackson Counties, South Dakota Executive Summary The U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service (NPS) proposes to implement a comprehensive black-tailed prairie dog management plan for the North Unit of Badlands National Park where prairie dog populations have increased from approximately 2,070 acres in 1979 to 6,363 acres in 2006, or 11% of the approximately 60,000 acres of available suitable habitat. The principal objectives of the management plan are to ensure that the black-tailed prairie dog is maintained in its role as a keystone species in the mixed-grass prairie ecosystem on the North Unit, while providing strategies to effectively manage instances of prairie dog encroachment onto adjacent private lands. The plan also seeks to manage the North Unit’s prairie dog populations to sustain numbers sufficient to survive unpredictable events that may cause high mortality, such as sylvatic plague, while at the same time allowing park managers to meet management goals for other North Unit resources. Primary considerations in developing the plan include conservation of the park’s natural processes and conditions, identification of effective tools for prairie dog management, implementing strategies to deal with prairie dog encroachment onto adjacent private lands, and protection of human health and safety. -

Cliff Chipmunk Tamias Dorsalis

Wyoming Species Account Cliff Chipmunk Tamias dorsalis REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: No special status USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Nongame Wildlife CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS3 (Bb), Tier II WYNDD: G5, S1 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Cliff Chipmunk (Tamias dorsalis) has no additional regulatory status or conservation rank considerations beyond those listed above. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are six recognized subspecies of Cliff Chipmunk, but only T. d. utahensis is found in Wyoming 1-5. Global chipmunk taxonomy remains disputed, with some arguing for three separate genera (i.e., Neotamias, Tamias, and Eutamias) 6-8, while others support the recognition of a single genus (i.e., Tamias) 9. Cliff Chipmunk was briefly referred to as N. dorsalis 10 but has recently been returned to the currently recognized genus Tamias, along with all other North American chipmunk species 11. Description: Cliff Chipmunk is a medium-large chipmunk that can be easily identified in the field by its mostly smoke gray upperparts, indistinct dorsal stripes (with the exception of one dark stripe along the spine), brown facial stripes, long bushy tail, stocky body, short legs, and white underbelly 2-5. This species exhibits sexual size dimorphism, with females averaging larger than males 2, 3. Adults weigh between 55–90 g with total length ranging from 208–240 mm 4. Tail, hind foot, and ear length range from 81–110 mm, 30–33 mm, and 17–21 mm, respectively 4. Within its Wyoming distribution, Cliff Chipmunk is easy to distinguish from Yellow-pine Chipmunk (T. -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

Fauna of the San Luis Valley Veryl F

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/22 Fauna of the San Luis Valley Veryl F. Keen, 1971, pp. 137-139 in: San Luis Basin (Colorado), James, H. L.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 22nd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 340 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1971 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

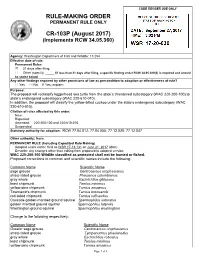

Filed As WSR 17-20-030 on September 27, 2017

CODE REVISER USE ONLY RULE-MAKING ORDER PERMANENT RULE ONLY CR-103P (August 2017) (Implements RCW 34.05.360) Agency: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife: 17-254 Effective date of rule: Permanent Rules ☒ 31 days after filing. ☐ Other (specify) (If less than 31 days after filing, a specific finding under RCW 34.05.380(3) is required and should be stated below) Any other findings required by other provisions of law as precondition to adoption or effectiveness of rule? ☐ Yes ☒ No If Yes, explain: Purpose: The proposal will reclassify loggerhead sea turtle from the state’s threatened subcategory (WAC 220-200-100) to state’s endangered subcategory (WAC 220-610-010). In addition, the proposal will classify the yellow-billed cuckoo under the state’s endangered subcategory (WAC 220-610-010). Citation of rules affected by this order: New: Repealed: Amended: 220-200-100 and 220-610-010. Suspended: Statutory authority for adoption: RCW 77.04.012; 77.04.055; 77.12.020; 77.12.047 Other authority: None. PERMANENT RULE (Including Expedited Rule Making) Adopted under notice filed as WSR 17-13-131 on June 21, 2017 (date). Describe any changes other than editing from proposed to adopted version: WAC 220-200-100 Wildlife classified as protected shall not be hunted or fished. Proposed corrections to common and scientific names include the following: Common Name Scientific Name sage grouse Centrocercus urophasianus sharp-tailed grouse Phasianus columbianus gray whale Eschrichtius gibbosus least chipmunk Tamius minimus yellow-pine chipmunk Tamius amoenus -

Species List

Species List M001 Opossum M025 Brazilian Free-tailed Bat M049 Mountain Pocket Gopher Didelphis virginiana Tadarida brasiliensis Thomomys monticola M002 Mount Lyell Shrew M026 Pika M050 Little Pocket Mouse Sorex lyelli Ochotona princeps Perognathus longimembris M003 Vagrant Shrew M027 Brush Rabbit M051 Great Basin Pocket Mouse Sorex vagrans Sylvilagus bachmani Perognathus parvus M004 Dusky Shrew M028 Desert Cottontail M052 Yellow-eared Pocket Mouse Sorex monticolus Sylvilagus audubonii Perognathus xanthonotus M005 Ornate Shrew M029 Snowshoe Hare M053 California Pocket Mouse Sorex ornatus Lepus americanus Perognathus californicus M006 Water Shrew M030 White-tailed Jackrabbit M054 Heermann's Kangaroo Rat Sorex palustris Lepus townsendii Dipodomys heermanni M007 Trowbridge's Shrew M031 Black-tailed Jackrabbit M055 California Kangaroo Rat Sorex trowbridgii Lepus californicus Dipodomys californicus M008 Shrew-mole M032 Mountain Beaver M056 Beaver Neurotrichus gibbsii Aplodontia rufa Castor canadensis M009 Broad-footed Mole M033 Alpine Chipmunk M057 Western Harvest Mouse Scapanus latimanus Eutamias alpinus Reithrodontomys megalotis M010 Little Brown Myotis M034 Least Chipmunk M058 California Mouse Myotis lucifugus Eutamias minimus Peromyscus californicus M011 Yuma Myotis M035 Yellow Pine Chipmunk M059 Deer Mouse Myotis yumanensis Eutamias amoenus Peromyscus maniculatus M012 Long-eared Myotis M036 Allen's Chipmunk M060 Brush Mouse Myotis evotis Eutamias senex Peromyscus boylii M013 Fringed Myotis M037 Sonoma Chipmunk M061 Piñon Mouse Myotis thysanodes -

Mammal Pests

VERTEBRATE PEST CONT ROL HANDBOOK - MAMMALS Mammal Pests Introduction This section contains methods used to control field rodents and rabbits and is a guide for agricultural commissioner personnel engaged in this work. Most pest mammals are discussed with specific control options. Rodenticides are often recommended. Before rodenticides are used, acceptance tests should be made to indicate the degree of bait acceptance that can be expected. If bait acceptance is good, most of the bait will be quickly consumed by rodents during a 24-hour period. If acceptance is poor, toxic bait should not be used. Too frequent application of acute toxic baits, like zinc phosphide, may cause bait and poison shyness. Unlike insecticides, which are generally applied to the crop itself, rodent baits are commonly placed in rodent burrows or applied to trails or areas where rodents naturally feed. Rodent baits should not be applied in any manner that will contaminate food or feed crops. This would include any application method which would cause the bait to lodge in food plants. Fumigants are applied directly into the rodent burrow and are sealed in by covering the burrow opening with a shovelful of dirt. Identifying Rodents Causing Damage to Crops One of the keys to controlling rodent damage in crops is prompt and accurate determination of which species is causing the damage. To make a positive species identification, survey the area of reported damage and look for signs of rodent activity such as: trails, runs, tracks and tail marks, droppings, burrows, nests and food caches. Also look for cuttings of grass or plant material in trails, runs or near burrow entrances. -

Phylogeny, Biogeography and Systematic Revision of Plain Long-Nosed Squirrels (Genus Dremomys, Nannosciurinae) Q ⇑ Melissa T.R

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94 (2016) 752–764 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeny, biogeography and systematic revision of plain long-nosed squirrels (genus Dremomys, Nannosciurinae) q ⇑ Melissa T.R. Hawkins a,b,c,d, , Kristofer M. Helgen b, Jesus E. Maldonado a,b, Larry L. Rockwood e, Mirian T.N. Tsuchiya a,b,d, Jennifer A. Leonard c a Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, National Zoological Park, Washington DC 20008, USA b Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington DC 20013-7012, USA c Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC), Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics Group, Avda. Americo Vespucio s/n, Sevilla 41092, Spain d George Mason University, Department of Environmental Science and Policy, 4400 University Drive, Fairfax, VA 20030, USA e George Mason University, Department of Biology, 4400 University Drive, Fairfax, VA 20030, USA article info abstract Article history: The plain long-nosed squirrels, genus Dremomys, are high elevation species in East and Southeast Asia. Received 25 March 2015 Here we present a complete molecular phylogeny for the genus based on nuclear and mitochondrial Revised 19 October 2015 DNA sequences. Concatenated mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees were constructed to determine Accepted 20 October 2015 the tree topology, and date the tree. All speciation events within the plain-long nosed squirrels (genus Available online 31 October 2015 Dremomys) were ancient (dated to the Pliocene or Miocene), and averaged older than many speciation events in the related Sunda squirrels, genus Sundasciurus. -

Tamias Ruficaudus Simulans, Red-Tailed Chipmunk

Conservation Assessment for the Red-Tailed Chipmunk (Tamias ruficaudus simulans) in Washington Jennifer Gervais May 2015 Oregon Wildlife Institute Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the red-tailed chipmunk (Tamias ruficaudus simulans). If you have information that will assist in conserving this species or questions concerning this Conservation Assessment, please contact the interagency Conservation Planning Coordinator for Region 6 Forest Service, BLM OR/WA in Portland, Oregon, via the Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program website at http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/sfpnw/issssp/contactus/ U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Executive Summary Species: Red-tailed chipmunk (Tamias ruficaudus) Taxonomic Group: Mammal Management Status: The red-tailed chipmunk is considered abundant through most of its range in western North America, but it is highly localized in Alberta, British Columbia, and Washington (Jacques 2000, Fig. 1). The species is made up of two fairly distinct subspecies, T. r. simulans in the western half of its range, including Washington, and T. r. ruficaudus in the east (e.g., Good and Sullivan 2001, Hird and Sullivan 2009). In British Columbia, T. r. simulans is listed as Provincial S3 or of conservation concern and is on the provincial Blue List (BC Conservation Data Centre 2014). The Washington Natural Heritage Program lists the red-tailed chipmunk’s global rank as G2, “critically imperiled globally because of extreme rarity or because of some factor(s) making it especially vulnerable to extinction,” and its state status as S2 although the S2 rank is uncertain. -

Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 ON THE COVER Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata) Photograph courtesy of Roger Christophersen, North Cascades National Park Complex Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 Roger G. Christophersen National Park Service North Cascades National Park Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 June 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner.