The Limits of Alias Analysis for Scalar Optimizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

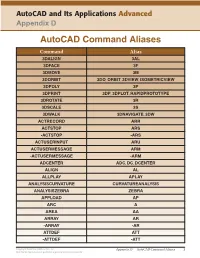

Autocad Command Aliases

AutoCAD and Its Applications Advanced Appendix D AutoCAD Command Aliases Command Alias 3DALIGN 3AL 3DFACE 3F 3DMOVE 3M 3DORBIT 3DO, ORBIT, 3DVIEW, ISOMETRICVIEW 3DPOLY 3P 3DPRINT 3DP, 3DPLOT, RAPIDPROTOTYPE 3DROTATE 3R 3DSCALE 3S 3DWALK 3DNAVIGATE, 3DW ACTRECORD ARR ACTSTOP ARS -ACTSTOP -ARS ACTUSERINPUT ARU ACTUSERMESSAGE ARM -ACTUSERMESSAGE -ARM ADCENTER ADC, DC, DCENTER ALIGN AL ALLPLAY APLAY ANALYSISCURVATURE CURVATUREANALYSIS ANALYSISZEBRA ZEBRA APPLOAD AP ARC A AREA AA ARRAY AR -ARRAY -AR ATTDEF ATT -ATTDEF -ATT Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 1 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias ATTEDIT ATE -ATTEDIT -ATE, ATTE ATTIPEDIT ATI BACTION AC BCLOSE BC BCPARAMETER CPARAM BEDIT BE BLOCK B -BLOCK -B BOUNDARY BO -BOUNDARY -BO BPARAMETER PARAM BREAK BR BSAVE BS BVSTATE BVS CAMERA CAM CHAMFER CHA CHANGE -CH CHECKSTANDARDS CHK CIRCLE C COLOR COL, COLOUR COMMANDLINE CLI CONSTRAINTBAR CBAR CONSTRAINTSETTINGS CSETTINGS COPY CO, CP CTABLESTYLE CT CVADD INSERTCONTROLPOINT CVHIDE POINTOFF CVREBUILD REBUILD CVREMOVE REMOVECONTROLPOINT CVSHOW POINTON Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 2 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias CYLINDER CYL DATAEXTRACTION DX DATALINK DL DATALINKUPDATE DLU DBCONNECT DBC, DATABASE, DATASOURCE DDGRIPS GR DELCONSTRAINT DELCON DIMALIGNED DAL, DIMALI DIMANGULAR DAN, DIMANG DIMARC DAR DIMBASELINE DBA, DIMBASE DIMCENTER DCE DIMCONSTRAINT DCON DIMCONTINUE DCO, DIMCONT DIMDIAMETER DDI, DIMDIA DIMDISASSOCIATE DDA DIMEDIT DED, DIMED DIMJOGGED DJO, JOG DIMJOGLINE DJL DIMLINEAR DIMLIN, DLI DIMORDINATE DOR, DIMORD DIMOVERRIDE DOV, DIMOVER DIMRADIUS DIMRAD, DRA DIMREASSOCIATE DRE DIMSTYLE D, DIMSTY, DST DIMTEDIT DIMTED DIST DI, LENGTH DIVIDE DIV DONUT DO DRAWINGRECOVERY DRM DRAWORDER DR Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. -

CS101 Lecture 9

How do you copy/move/rename/remove files? How do you create a directory ? What is redirection and piping? Readings: See CCSO’s Unix pages and 9-2 cp option file1 file2 First Version cp file1 file2 file3 … dirname Second Version This is one version of the cp command. file2 is created and the contents of file1 are copied into file2. If file2 already exits, it This version copies the files file1, file2, file3,… into the directory will be replaced with a new one. dirname. where option is -i Protects you from overwriting an existing file by asking you for a yes or no before it copies a file with an existing name. -r Can be used to copy directories and all their contents into a new directory 9-3 9-4 cs101 jsmith cs101 jsmith pwd data data mp1 pwd mp1 {FILES: mp1_data.m, mp1.m } {FILES: mp1_data.m, mp1.m } Copy the file named mp1_data.m from the cs101/data Copy the file named mp1_data.m from the cs101/data directory into the pwd. directory into the mp1 directory. > cp ~cs101/data/mp1_data.m . > cp ~cs101/data/mp1_data.m mp1 The (.) dot means “here”, that is, your pwd. 9-5 The (.) dot means “here”, that is, your pwd. 9-6 Example: To create a new directory named “temp” and to copy mv option file1 file2 First Version the contents of an existing directory named mp1 into temp, This is one version of the mv command. file1 is renamed file2. where option is -i Protects you from overwriting an existing file by asking you > cp -r mp1 temp for a yes or no before it copies a file with an existing name. -

Expression Rematerialization for VLIW DSP Processors with Distributed Register Files ?

Expression Rematerialization for VLIW DSP Processors with Distributed Register Files ? Chung-Ju Wu, Chia-Han Lu, and Jenq-Kuen Lee Department of Computer Science, National Tsing-Hua University, Hsinchu 30013, Taiwan {jasonwu,chlu}@pllab.cs.nthu.edu.tw,[email protected] Abstract. Spill code is the overhead of memory load/store behavior if the available registers are not sufficient to map live ranges during the process of register allocation. Previously, works have been proposed to reduce spill code for the unified register file. For reducing power and cost in design of VLIW DSP processors, distributed register files and multi- bank register architectures are being adopted to eliminate the amount of read/write ports between functional units and registers. This presents new challenges for devising compiler optimization schemes for such ar- chitectures. This paper aims at addressing the issues of reducing spill code via rematerialization for a VLIW DSP processor with distributed register files. Rematerialization is a strategy for register allocator to de- termine if it is cheaper to recompute the value than to use memory load/store. In the paper, we propose a solution to exploit the character- istics of distributed register files where there is the chance to balance or split live ranges. By heuristically estimating register pressure for each register file, we are going to treat them as optional spilled locations rather than spilling to memory. The choice of spilled location might pre- serve an expression result and keep the value alive in different register file. It increases the possibility to do expression rematerialization which is effectively able to reduce spill code. -

Equality Saturation: a New Approach to Optimization

Logical Methods in Computer Science Vol. 7 (1:10) 2011, pp. 1–37 Submitted Oct. 12, 2009 www.lmcs-online.org Published Mar. 28, 2011 EQUALITY SATURATION: A NEW APPROACH TO OPTIMIZATION ROSS TATE, MICHAEL STEPP, ZACHARY TATLOCK, AND SORIN LERNER Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of California, San Diego e-mail address: {rtate,mstepp,ztatlock,lerner}@cs.ucsd.edu Abstract. Optimizations in a traditional compiler are applied sequentially, with each optimization destructively modifying the program to produce a transformed program that is then passed to the next optimization. We present a new approach for structuring the optimization phase of a compiler. In our approach, optimizations take the form of equality analyses that add equality information to a common intermediate representation. The op- timizer works by repeatedly applying these analyses to infer equivalences between program fragments, thus saturating the intermediate representation with equalities. Once saturated, the intermediate representation encodes multiple optimized versions of the input program. At this point, a profitability heuristic picks the final optimized program from the various programs represented in the saturated representation. Our proposed way of structuring optimizers has a variety of benefits over previous approaches: our approach obviates the need to worry about optimization ordering, enables the use of a global optimization heuris- tic that selects among fully optimized programs, and can be used to perform translation validation, even on compilers other than our own. We present our approach, formalize it, and describe our choice of intermediate representation. We also present experimental results showing that our approach is practical in terms of time and space overhead, is effective at discovering intricate optimization opportunities, and is effective at performing translation validation for a realistic optimizer. -

Shell Variables

Shell Using the command line Orna Agmon ladypine at vipe.technion.ac.il Haifux Shell – p. 1/55 TOC Various shells Customizing the shell getting help and information Combining simple and useful commands output redirection lists of commands job control environment variables Remote shell textual editors textual clients references Shell – p. 2/55 What is the shell? The shell is the wrapper around the system: a communication means between the user and the system The shell is the manner in which the user can interact with the system through the terminal. The shell is also a script interpreter. The simplest script is a bunch of shell commands. Shell scripts are used in order to boot the system. The user can also write and execute shell scripts. Shell – p. 3/55 Shell - which shell? There are several kinds of shells. For example, bash (Bourne Again Shell), csh, tcsh, zsh, ksh (Korn Shell). The most important shell is bash, since it is available on almost every free Unix system. The Linux system scripts use bash. The default shell for the user is set in the /etc/passwd file. Here is a line out of this file for example: dana:x:500:500:Dana,,,:/home/dana:/bin/bash This line means that user dana uses bash (located on the system at /bin/bash) as her default shell. Shell – p. 4/55 Starting to work in another shell If Dana wishes to temporarily use another shell, she can simply call this shell from the command line: [dana@granada ˜]$ bash dana@granada:˜$ #In bash now dana@granada:˜$ exit [dana@granada ˜]$ bash dana@granada:˜$ #In bash now, going to hit ctrl D dana@granada:˜$ exit [dana@granada ˜]$ #In original shell now Shell – p. -

Precise Null Pointer Analysis Through Global Value Numbering

Precise Null Pointer Analysis Through Global Value Numbering Ankush Das1 and Akash Lal2 1 Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 2 Microsoft Research, Bangalore, India Abstract. Precise analysis of pointer information plays an important role in many static analysis tools. The precision, however, must be bal- anced against the scalability of the analysis. This paper focusses on improving the precision of standard context and flow insensitive alias analysis algorithms at a low scalability cost. In particular, we present a semantics-preserving program transformation that drastically improves the precision of existing analyses when deciding if a pointer can alias Null. Our program transformation is based on Global Value Number- ing, a scheme inspired from compiler optimization literature. It allows even a flow-insensitive analysis to make use of branch conditions such as checking if a pointer is Null and gain precision. We perform experiments on real-world code and show that the transformation improves precision (in terms of the number of dereferences proved safe) from 86.56% to 98.05%, while incurring a small overhead in the running time. Keywords: Alias Analysis, Global Value Numbering, Static Single As- signment, Null Pointer Analysis 1 Introduction Detecting and eliminating null-pointer exceptions is an important step towards developing reliable systems. Static analysis tools that look for null-pointer ex- ceptions typically employ techniques based on alias analysis to detect possible aliasing between pointers. Two pointer-valued variables are said to alias if they hold the same memory location during runtime. Statically, aliasing can be de- cided in two ways: (a) may-alias [1], where two pointers are said to may-alias if they can point to the same memory location under some possible execution, and (b) must-alias [27], where two pointers are said to must-alias if they always point to the same memory location under all possible executions. -

A Formally-Verified Alias Analysis

A Formally-Verified Alias Analysis Valentin Robert1;2 and Xavier Leroy1 1 INRIA Paris-Rocquencourt 2 University of California, San Diego [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. This paper reports on the formalization and proof of sound- ness, using the Coq proof assistant, of an alias analysis: a static analysis that approximates the flow of pointer values. The alias analysis con- sidered is of the points-to kind and is intraprocedural, flow-sensitive, field-sensitive, and untyped. Its soundness proof follows the general style of abstract interpretation. The analysis is designed to fit in the Comp- Cert C verified compiler, supporting future aggressive optimizations over memory accesses. 1 Introduction Alias analysis. Most imperative programming languages feature pointers, or object references, as first-class values. With pointers and object references comes the possibility of aliasing: two syntactically-distinct program variables, or two semantically-distinct object fields can contain identical pointers referencing the same shared piece of data. The possibility of aliasing increases the expressiveness of the language, en- abling programmers to implement mutable data structures with sharing; how- ever, it also complicates tremendously formal reasoning about programs, as well as optimizing compilation. In this paper, we focus on optimizing compilation in the presence of pointers and aliasing. Consider, for example, the following C program fragment: ... *p = 1; *q = 2; x = *p + 3; ... Performance would be increased if the compiler propagates the constant 1 stored in p to its use in *p + 3, obtaining ... *p = 1; *q = 2; x = 4; ... This optimization, however, is unsound if p and q can alias. -

Practical and Accurate Low-Level Pointer Analysis

Practical and Accurate Low-Level Pointer Analysis Bolei Guo Matthew J. Bridges Spyridon Triantafyllis Guilherme Ottoni Easwaran Raman David I. August Department of Computer Science, Princeton University {bguo, mbridges, strianta, ottoni, eraman, august}@princeton.edu Abstract High−Level IR Low−Level IR Pointer SuperBlock .... Inlining Opti Scheduling .... Analysis Formation Pointer analysis is traditionally performed once, early Source Machine Code Code in the compilation process, upon an intermediate repre- Lowering sentation (IR) with source-code semantics. However, per- forming pointer analysis only once at this level imposes a Figure 1. Traditional compiler organization phase-ordering constraint, causing alias information to be- char A[10],B[10],C[10]; . come stale after subsequent code transformations. More- foo() { int i; over, high-level pointer analysis cannot be used at link time char *p; or run time, where the source code is unavailable. for (i=0;i<10;i++) { if (...) 1: p = A 2: p = B 1: p = A 2: p = B This paper advocates performing pointer analysis on a 1: p = A; 3': C[i] = p[i] 3: C[i] = p[i] else low-level intermediate representation. We present the first 2: p = B; 4': A[i] = ... 4: A[i] = ... 3: C[i] = p[i]; context-sensitive and partially flow-sensitive points-to anal- 4: A[i] = ...; 3: C[i] = p[i] } 4: A[i] = ... ysis designed to operate at the assembly level. As we will } demonstrate, low-level pointer analysis can be as accurate (a) Source code (b) Source code CFG (c) Transformed code CFG as high-level analysis. Additionally, our low-level pointer analysis also enables a quantitative comparison of prop- agating high-level pointer analysis results through subse- Figure 2. -

Linux Cheat Sheet

1 of 4 ########################################### # 1.1. File Commands. # Name: Bash CheatSheet # # # # A little overlook of the Bash basics # ls # lists your files # # ls -l # lists your files in 'long format' # Usage: A Helpful Guide # ls -a # lists all files, including hidden files # # ln -s <filename> <link> # creates symbolic link to file # Author: J. Le Coupanec # touch <filename> # creates or updates your file # Date: 2014/11/04 # cat > <filename> # places standard input into file # Edited: 2015/8/18 – Michael Stobb # more <filename> # shows the first part of a file (q to quit) ########################################### head <filename> # outputs the first 10 lines of file tail <filename> # outputs the last 10 lines of file (-f too) # 0. Shortcuts. emacs <filename> # lets you create and edit a file mv <filename1> <filename2> # moves a file cp <filename1> <filename2> # copies a file CTRL+A # move to beginning of line rm <filename> # removes a file CTRL+B # moves backward one character diff <filename1> <filename2> # compares files, and shows where differ CTRL+C # halts the current command wc <filename> # tells you how many lines, words there are CTRL+D # deletes one character backward or logs out of current session chmod -options <filename> # lets you change the permissions on files CTRL+E # moves to end of line gzip <filename> # compresses files CTRL+F # moves forward one character gunzip <filename> # uncompresses files compressed by gzip CTRL+G # aborts the current editing command and ring the terminal bell gzcat <filename> # -

Aliases, Intro. to Optimization

Aliasing Two variables are aliased if they can refer to the same storage location. Possible Sources:pointers, parameter passing, storage overlap... Ex. address of a passed x and y are aliased! Pointer Analysis, Alias Analysis to get less conservative info Needed for correct, aggressive optimization Procedures: terminology a, e global b,c formal arguments d local call site with actual arguments At procedure call, formals bound to actuals, may be aliased Ex. (b,a) , (c, d) Globals, actuals may be modified, used Ex. a, b Call Graphs Determines possible flow of control, interprocedurally G = (N, LE, s) N set of nodes LE set of labelled edges n m s start node Qu: Why need call site labels? Why list? Example Call Graph 1,2 3 4 5 6 7 Interprocedural Dataflow Analysis Based on call graph: forward, backward Gen, Kill: Need to summarize procedures per call Flow sensitive: take procedure's control flow into account Flow insensitive: ignore procedure's control flow Difficulties: Hard, complex Flow sensitive alias analysis intractable Separate compilation? Scale compiler can do both flow sensitive and insensitive Most compilers ultraconservative, or flow insensitive Scalar Replacement of Aggregates Use scalar temporary instead of aggregate variable Compiler may limit optimization to such scalars Can do better register allocation, constant propagation,... Particulary useful when small number of constant values Can use constant propagation, dead code elimination to specialize code Value Numbering of Basic Blocks Eliminates computations whose values are already computed in BB value needn't be constant Method: Value Number Hash Table Global Copy Propagation Given A:=B, replace later uses of A by B, as long as A,B not redefined (with dead code elim) Global Copy Propagation Ex. -

Configuring Your Login Session

SSCC Pub.# 7-9 Last revised: 5/18/99 Configuring Your Login Session When you log into UNIX, you are running a program called a shell. The shell is the program that provides you with the prompt and that submits to the computer commands that you type on the command line. This shell is highly configurable. It has already been partially configured for you, but it is possible to change the way that the shell runs. Many shells run under UNIX. The shell that SSCC users use by default is called the tcsh, pronounced "Tee-Cee-shell", or more simply, the C shell. The C shell can be configured using three files called .login, .cshrc, and .logout, which reside in your home directory. Also, many other programs can be configured using the C shell's configuration files. Below are sample configuration files for the C shell and explanations of the commands contained within these files. As you find commands that you would like to include in your configuration files, use an editor (such as EMACS or nuTPU) to add the lines to your own configuration files. Since the first character of configuration files is a dot ("."), the files are called "dot files". They are also called "hidden files" because you cannot see them when you type the ls command. They can only be listed when using the -a option with the ls command. Other commands may have their own setup files. These files almost always begin with a dot and often end with the letters "rc", which stands for "run commands". -

Configuration and Administration of Networking for Fedora 23

Fedora 23 Networking Guide Configuration and Administration of Networking for Fedora 23 Stephen Wadeley Networking Guide Draft Fedora 23 Networking Guide Configuration and Administration of Networking for Fedora 23 Edition 1.0 Author Stephen Wadeley [email protected] Copyright © 2015 Red Hat, Inc. and others. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https://fedoraproject.org/wiki/ Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries.