Abstracts and Biographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

Stoically Sapphic: Gentlemanly Encryption and Disruptive Legibility in Adapting Anne Lister

Stoically Sapphic: Gentlemanly Encryption and Disruptive Legibility in Adapting Anne Lister Sarah E. Maier and Rachel M. Friars (University of New Brunswick, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada & Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Abstract: Anne Lister (1791–1840) was a multihyphenate landowner-gentry-traveller-autodidact- queer-lesbian, a compulsive journal writer who lived through the late-Romantic and well into the Victorian ages. While her journals have proven to be an iconographic artefact for queer and lesbian history, our interest here is in the public adaptations of Lister’s intentionally private writings for twenty-first-century audiences as found in the film The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister (2010) and the television series Gentleman Jack (2019–). Our discussion queries what it means to portray lived queer experience of the nineteenth century, how multimedia translate and transcribe Lister’s works onto screen, as well as how questions of legibility, visibility and ethics inevitably emerge in these processes. Keywords: adaptation, encryption, Gentleman Jack, journals, lesbianism, Anne Lister, queer history, queer visibility, The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister, transcription. ***** Lister ought to tell her own story before anyone interpreted it for her. Hers is, after all, the truly authentic voice of the nineteenth century woman caught up in a dilemma not of her own making. She ought to be allowed to tell it as it was, from her own point of view. (Whitbread 1992: xii) The recent appearance of a woman given the nickname ‘Gentleman Jack’ in a show focused on a queer woman depicts a subject who writes her life into encrypted journals. -

Maria Kyriacou

MINUTES SEASON 8 1 3 THE EUROPEAN SERIES SUMMIT JULY FONTAINEBLEAU - FRANCE 2019 CREATION EDITORIAL TAKES POWER! This mantra, also a pillar of Série Series’ identity, steered Throughout the three days, we shone a light on people the exciting 8th edition which brought together 700 whose outlook and commitment we particularly European creators and decision-makers. connected with. Conversations and insight are the DNA of Série Series and this year we are proud to have During the three days, we invited attendees to question facilitated particularly rich conversations; to name but the idea of power. Both in front and behind the camera, one, Sally Wainwright’s masterclass where she spoke of power plays are omnipresent and yet are rarely her experience and her vision with a fellow heavyweight deciphered. Within an industry that is booming, areas in British television, Jed Mercurio. Throughout these of power multiply and collide. But deep down, what is Minutes, we hope to convey the essence of these at the heart of power today: is it the talent, the money, conversations, putting them into context and making the audience? Who is at the helm of series production: them available to all. the creators, the funders, the viewers? In these Minutes, through our speakers’ analyses and stories, we hope to For the first time, this year, we have also wanted to o er you some food for thought, if not an answer. broaden our horizons and o er a “white paper” as an opening to the reports, focusing on the theme of Creators, producers, broadcasters: this edition’s power, through the points of view that were expressed 120 speakers flew the flag for daring and innovative throughout the 8 editions and the changes that Série 3 European creativity and are aware of the need for the Series has welcomed. -

Scott & Bailey 2 Wylie Interviews

Written by Sally Wainwright 2 PRODUCTION NOTES Introduction .........................................................................................Page 3 Regular characters .............................................................................Page 4 Interview with writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright ...................Page 5 Interview with co-creator Diane Taylor .............................................Page 8 Suranne Jones is D.C. Rachel Bailey ................................................Page 11 Lesley Sharp is D.C. Janet Scott .......................................................Page 14 Amelia Bullmore is D.C.I. Gill Murray ................................................Page 17 Nicholas Gleaves is D.S. Andy Roper ...............................................Page 20 Sean Maguire is P.C. Sean McCartney ..............................................Page 23 Lisa Riley is Nadia Hicks ....................................................................Page 26 Kevin Doyle is Geoff Hastings ...........................................................Page 28 3 INTRODUCTION Suranne Jones and Lesley Sharp resume their partnership in eight new compelling episodes of the northern-based crime drama Scott & Bailey. Acclaimed writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright has written the second series after once again joining forces with Consultancy Producer Diane Taylor, a retired Detective from Greater Manchester Police. Their unique partnership allows viewers and authentic look at the realities and responsibilities of working within -

Class and Gender Identify in the Film Transpositions of Emily Brontë's

Seijo Richart 1 Appendix II: Transpositions of Wuthering Heights to other Media 1. Television 1.1. TV - films 1948 Wuthering Heights. Adapt. John Davidson (from his stage play). BBC TV. 1948 Wuthering Heights. Kraft Television Theatre, NBC (USA). TV broadcast of a performance of Rudolph Carter’s theatre transposition. Only the first half of the novel. 1950 “Wuthering Heights”. Westinghouse's Studio One. Perf. Charlton Heston. USA. 1953 Wuthering Heights. Perf. Richard Todd and Yvonne Mitchell. BBC TV (UK). Script by Nigel Kneale, based on Rudolph Carter’s theatre transposition. 1958 Wuthering Heights. Perf. Richard Burton and Rosemary Harris. UK 1962 Wuthering Heights. Perf. Keith Mitchell and Claire Bloom. BBC TV (UK). Script by Nigel Kneale, based on Rudolph Carter’s theatre transposition. 1998 Wuthering Heights. Dir. David Skynner. Perf. Robert Kavanah, Orla Brady. Script by Neil McKay. London Weekend Television. 2003 Wuthering Heights. Dir. Suri Kirshnamma. Writ. Max Enscoe. Perf. Erika Christensen, Mike Vogel. MTV Films. 1.2. TV Series 1956 Cime tempestose. Dir. Mario Landi. Italy. 1963. Cumbres Borrascosas. Dir & Prod. Daniel Camino. Perú. 1964 Cumbres Borrascosas. Dir. Manuel Calvo. Prod. Ernesto Alonso (Eduardo/ Edgar in Abismos). Forty-five episodes. México. 1967 Wuthering Heights. Dir. Peter Sasdy. Adapt. Hugh Leonard. Perf. Ian McShane, Angela Scoular. Four parts serial. BBC TV (UK). 1967 O Morro dos Ventos Uivantes. Adap. Lauro César Muniz. TV Excelsior (Brasil). 1968 Les Hauts de Hurlevent. Dir. Jean-Paul Carrère. France. Two parts. Early 1970s A serialised version in the Egyptian television. 1973 Vendaval. Adapt. Ody Fraga. Perf. Joana Fomm. TV Record (Brasil). 1976 Cumbres Borrascosas. -

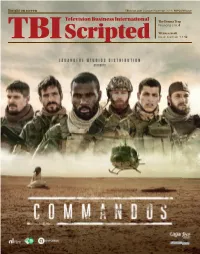

Scriptedpofc Octnov19.Indd

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | October/November 2019 | MIPCOM Issue Television Business International e Drama Trap Financing a hit 4 Writers revolt TBI Scripted Inside Kontrakt '18 12 ScriptedpOFC OctNov19.indd 1 03/10/2019 00:36 LAGARDERE_COMMANDO_TBI_COVER_def.indd 1 19/09/2019 15:49 BASED ON THE AWARD-WINNING NOVELS ON THE AWARD-WINNING BASED A NEW ORIGINAL SERIES p02-03 ITV Noughts & Crosses OctNov19.indd 2 02/10/2019 15:18 ITV0272_NOXO_TBIMipMain_IFCDPS_SubAW.indd All Pages 02/10/2019 14:08 BASED ON THE AWARD-WINNING NOVELS ON THE AWARD-WINNING BASED A NEW ORIGINAL SERIES p02-03 ITV Noughts & Crosses OctNov19.indd 3 02/10/2019 15:18 ITV0272_NOXO_TBIMipMain_IFCDPS_SubAW.indd All Pages 02/10/2019 14:08 Genre: Drama | Duration: 6x60' VISIT US AT MIPCOM, STAND R8.C9, RIVIERA 8 Catalogue: www.keshetinternational.com Contact us: [email protected] @KeshetIntl | KeshetInternational | @KeshetInternational ScriptedpXX Keshet Keeler OctNov19.indd 1 24/09/2019 12:49 TBI Scripted | This Issue Contents October/November 2019 4. Inside the multi-million dollar drama trap Contact us High-end scripted product has never been more lucrative but it also carries increasing risk, so how can producers and distributors navigate these challenging times? Editor Manori Ravindran [email protected] 8. Duking it out with global drama Direct line +44 (0) 20 3377 3832 TBI takes a trip to Ireland to find out about A+E Networks International’s uniquely Twitter @manori_r funded drama Miss Scarlet And The Duke. Managing editor Richard Middleton 12. When writers revolt [email protected] Creative talent might be in demand but writers from LA to Berlin feel they aren’t Direct line +44 (0) 20 7017 7184 being given the recognition they deserve. -

Tim Fywell Director

Tim Fywell Director Film & Television 2018 GRANTCHESTER – Series 4 Lead director Kudos Productions for ITV OUTLAWS Attached to direct feature film written by Rachel Cuperman & Sally Griffiths In development with Samuelson Productions 2017 OUR GIRL – Series 3 Directed opening 2 episodes of BBC1 drama Written by Tony Grounds, Produced by Tim Whitby 2016-7 GRANTCHESTER – Series 3 Lead Director, 2 x 60’ episodes Lovely Day Productions for ITV 2016 BLACK ROAD Directed Short Film Written by Michelle Bonnard, Starring Michelle Collins Produced by Debbie Gray, Genesius Pictures Winner, Best Short Film, European Short Film Festival 2016 2015 GRANTCHESTER – Series 2 Lead Director, 2 x 60’ episodes Lovely Day Productions for ITV 2015 ALYS, ALWAYS Feature film adaptation of novel by Harriet Lane Developed with Sixteen Films 2014/15 RIVER Directed 2 x 60’ episodes. Kudos for BBC One Written by Abi Morgan, Produced by Chris Carey Starring Stellan Skarsgard, Nicola Walker and Lesley Manville Winner, Golden Nymph, Best TV Series Drama, Festival de Television de Monte Carlo 2016 Winner, Drama Series, Rose d’Or Awards 2016 2014 GRANTCHESTER – Series 1 Directed 2 x 60’ episodes. Lovely Day Productions for ITV Written by Daisy Coulam, based on the short stories by James Runcie Starring James Norton and Robson Green Produced by Emma Kingsman-Lloyd HAPPY VALLEY – Series 1 Directed 2 x 60’ episodes. Red Productions for BBC One Written by Sally Wainwright, Produced by Karen Lewis Starring: Sarah Lancaster, James Norton and Siobhan Finneran Winner, Golden Nymph, Best European Drama Series, Monte Carlo TV Festival 2015 Winner, BAFTA TV Award for Best Drama Series, 2015 2013 DRACULA Directed 2 x 60’ episodes for Carnival / NBC Created by Cole Haddon Starring Jonathan Rhys Myers 2013 MASTERS OF SEX – Series 1 Directed 1 x 60’ episode for Showtime Developed for television by Michelle Ashford Starring Michael Sheen, Lizzie Caplan and Alison Janney Nominated for Best Drama Series, Golden Globe Awards 2014 2013 WODEHOUSE IN EXILE Directed single TV film. -

Lesley Sharp and the Alternative Geographies of Northern English Stardom

This is a repository copy of Lesley sharp and the alternative geographies of northern english stardom. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95675/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Forrest, D. and Johnson, B. (2016) Lesley sharp and the alternative geographies of northern english stardom. Journal of Popular Television, 4 (2). pp. 199-212. ISSN 2046-9861 https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv.4.2.199_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Lesley Sharp and the alternative geographies of Northern English Stardom David Forrest, University of Sheffield Beth Johnson, University of Leeds Abstract Historically, ‘North’ (of England) is a byword for narratives of economic depression, post-industrialism and bleak and claustrophobic representations of space and landscape. -

Copyrighted Material

1 Experimentation and the Early Writings Christine Alexander Juvenilia, or youthful writings, are by their nature experimental. They represent a creative intervention whereby a novice explores habits of thought and behavior, ideas about society and personal space, and modes of literary expression. It is a truism to say that youth is a time of exploration and testing. Any child psychologist will tell you that the teenage years in particular are a time of trial and error, a time when limits are tested in order to push boundaries and gain new adult freedoms. Juvenilia embody this same journey toward so‐called maturity, involving the imitation and examination of the adult world. And because early writing is generally a private occupation, practiced without fear of parental interfer- ence or the constraints of literary censorship, the young writer is free to interrogate current political, social, and personal discourses. As writing that embraces this creative and intel- lectual freedom, Charlotte Brontë’s juvenilia are a valuable source for investigating the literary experimentation of an emerging author seeking to establish a writing self. This chapter will examine the ways that Charlotte Brontë used her authorial role to engage with the world around her and to test her agency in life and literature. The first focus will be on the importance of a self‐contained, paracosmic, or imaginary world for facilitating experiment and engagement with political, social, and historical events. The second will be on the way Brontë experimented with print culture and narrative to con- struct a self‐reflexive, dialectic method that allowed her to interrogate both the “real” world and her paracosmicCOPYRIGHTED world. -

To Walk Invisible: the Brontë Sisters

Our Brother’s Keepers: On Writing and Caretaking in the Brontë Household: Review of To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters Shannon Scott (University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA) To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters Writer & Director, Sally Wainwright BBC Wales, 2016 (TV film) Universal Pictures 2017 (DVD) ***** In Sally Wainwright’s To Walk Invisible, a two-part series aired on BBC and PBS in 2016, there are no rasping coughs concealed under handkerchiefs, no flashbacks to Cowen Bridge School, no grief over the loss of a sister; instead, there is baking bread, invigorating walks on the moor, and, most importantly, writing. Wainwright dramatises three prolific years in the lives of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë when they composed their first joint volume of poetry and their first sole-authored novels: The Professor, rejected and abandoned for Jane Eyre (1847), Wuthering Heights (1847), and Agnes Grey (1847), respectively. The young women are shown writing in the parlour surrounded by tidy yet threadbare furniture, at the kitchen table covered in turnips and teacups, composing out loud on the way to town for more paper, or while resting in the flowering heather. For Charlotte, played with a combination of reserve and deep emotion by Finn Atkins, to “walk invisible” refers to their choice to publish under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, but in Wainwright’s production, it also refers to invisibility in the home, as the sisters quietly take care of their aging and nearly-blind father, Reverend Patrick Brontë (Jonathan Price), and deal with the alcoholism and deteriorating mental illness of their brother, Branwell (Adam Nogaitis). -

HBO/BBC Drama Series GENTLEMAN JACK, Created, Written and Directed by Sally Wainwright, Debuts April 22 on HBO

HBO/BBC drama series GENTLEMAN JACK, created, written and directed by Sally Wainwright, debuts April 22 on HBO The HBO/BBC drama series GENTLEMAN JACK begins its eight-episode season MONDAY, APRIL 22 (10:00-11:00 p.m. ET/PT) on HBO. Created, written and co-directed by Sally Wainwright (“Happy Valley,” “Last Tango in Halifax”), and starring BAFTA Award winner Suranne Jones (“Doctor Foster,” “Save Me”), GENTLEMAN JACK tells the story of a woman who had a passion for life and a mind for business, and bucked society’s expectations at every turn. The series will also be available on HBO NOW, HBO GO, HBO On Demand and partners’ streaming platforms. GENTLEMAN JACK will air in the UK on BBC One this spring. Set in the complex, changing world of 1832 Halifax, West Yorkshire – the cradle of the evolving Industrial Revolution – GENTLEMAN JACK focuses on landowner Anne Lister, who is determined to transform the fate of her faded ancestral home, Shibden Hall, by reopening the coal mines and marrying well. The charismatic, single-minded, swashbuckling Lister – who dresses head-to-toe in black and charms her way into high society – has no intention of marrying a man. The story examines Lister’s relationships with her family, servants, tenants and industrial rivals and, most importantly, would-be wife. Based in historical fact, the real-life Anne Lister’s story was recorded in the four million words of her diaries, and the most intimate details of her life, once hidden in a secret code, have been decoded and revealed for the series. -

Anne Lister on Gentleman Jack: Queerness, Class, and Prestige in “Quality” Period Dramas

International Journal of Communication 15(2021), 2397–2417 1932–8036/20210005 The “Gentleman-like” Anne Lister on Gentleman Jack: Queerness, Class, and Prestige in “Quality” Period Dramas EVE NG1 Ohio University, USA This article examines the significance of queerness to class and prestige illustrated by the series Gentleman Jack (BBC/HBO, 2019–present). Although previous scholarship has discussed LGBTQ content and network brands, the development of “quality” television, and the status of period (heritage) drama, there has not been significant consideration about the relationships among all these elements. Based on the life of the 19th-century Englishwoman Anne Lister, Gentleman Jack depicts Lister’s gender and sexual nonconformity—particularly her romantic interactions with women and her mobility through the world—as a charming, cosmopolitan queerness, without addressing how this depended on her elite status. The cachet of GJ’s queer content interacts with both the prestige of the period genre and the BBC’s and HBO’s quality TV brands, with the show illustrating how narratives in “post-heritage” drama can gesture toward critique of class, race, and nationality privileges while continuing to be structured by these hierarchies. This article points to new avenues for theorizing how prestige in television is constructed through the interaction of content, genre, and production contexts. Keywords: BBC television, class representation, HBO, heritage drama, LGBTQ media, period drama, post-heritage drama, quality television, queer representation Gentleman Jack (hereafter GJ), a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) television series coproduced with Home Box Office (HBO),2 has attracted critical attention for exuberantly depicting how the 19th-century Englishwoman Anne Lister challenged the norms of gender presentation and sexuality as “the first modern lesbian” (Roulston, 2013), with the series taking its title from a derogatory nickname that Lister earned from her masculine appearance and demeanor.