The Day-Of-The-Week Effect in the Saudi Stock Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Exchange of Choice Overview of JPX Who We Are

Your Exchange of Choice Overview of JPX Who we are... Japan Exchange Group, Inc. (JPX) was formed through the merger between Tokyo Stock Exchange Group and Osaka Securities Exchange in January 2013. In 1878, soon after the Meiji Restoration, Eiichi Shibusawa, who is known as the father of capitalism in Japan, established Tokyo Stock Exchange. That same year, Tomoatsu Godai, a businessman who was instrumental in the economic development of Osaka, established Osaka Stock Exchange. This year marks the 140th anniversary of their founding. JPX has inherited the will of both Eiichi Shibusawa and Tomoatsu Godai as the pioneers of capitalism in modern Japan and is determined to contribute to drive sustainable growth of the Japanese economy. Contents Strategies for Overview of JPX Creating Value 2 Corporate Philosophy and Creed 14 Message from the CEO 3 The Role of Exchange Markets 18 Financial Policies 4 Business Model 19 IT Master Plan 6 Creating Value at JPX 20 Core Initiatives 8 JPX History 20 Satisfying Diverse Investor Needs and Encouraging Medium- to Long-Term Asset 10 Five Years since the Birth of JPX - Building Milestone Developments 21 Supporting Listed Companies in Enhancing Corporate Value 12 FY2017 Highlights 22 Fulfilling Social Mission by Reinforcing Market Infrastructure 23 Creating New Fields of Exchange Business Editorial Policy Contributing to realizing an affluent society by promoting sustainable development of the market lies at the heart of JPX's corporate philosophy. We believe that our efforts to realize this corporate philosophy will enable us to both create sustainable value and fulfill our corporate social responsibility. Our goal in publishing this JPX Report 2018 is to provide readers with a deeper understanding of this idea and our initiatives in business activities. -

Assessing for the Volatility of the Saudi, Dubai and Kuwait Stock Markets: TIME SERIES ANALYSIS (2005-2016)

Assessing for the volatility of the Saudi, Dubai and Kuwait stock markets: TIME SERIES ANALYSIS (2005-2016) Yazeed Abdulaziz I Bin Ateeq This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics Manchester Metropolitan University 2018 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my dad and mum Mr. Abdulaziz Bin Ateeq & Mrs Al Jawhara Bin Dayel My wife Afnan My Greatest boys Muhanad & Abdulaziz My lovely sisters Salwa & Hissa Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………. VII DECLARATION …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… VIII List of Acronyms ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….IX ABSTRACT………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………….… X CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background of research .................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Justification of research .................................................................................................................... 4 1.3. The motivation of the study .............................................................................................................. 7 1.4. Research Questions and Objectives: ................................................................................................ -

Enhancing Liquidity in Emerging Market Exchanges

ENHANCING LIQUIDITY IN EMERGING MARKET EXCHANGES ENHANCING LIQUIDITY IN EMERGING MARKET EXCHANGES OLIVER WYMAN | WORLD FEDERATION OF EXCHANGES 1 CONTENTS 1 2 THE IMPORTANCE OF EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GROWING LIQUIDITY page 2 page 5 3 PROMOTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF A DIVERSE INVESTOR BASE page 10 AUTHORS Daniela Peterhoff, Partner Siobhan Cleary Head of Market Infrastructure Practice Head of Research & Public Policy [email protected] [email protected] Paul Calvey, Partner Stefano Alderighi Market Infrastructure Practice Senior Economist-Researcher [email protected] [email protected] Quinton Goddard, Principal Market Infrastructure Practice [email protected] 4 5 INCREASING THE INVESTING IN THE POOL OF SECURITIES CREATION OF AN AND ASSOCIATED ENABLING MARKET FINANCIAL PRODUCTS ENVIRONMENT page 18 page 28 6 SUMMARY page 36 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Trading venue liquidity is the fundamental enabler of the rapid and fair exchange of securities and derivatives contracts between capital market participants. Liquidity enables investors and issuers to meet their requirements in capital markets, be it an investment, financing, or hedging, as well as reducing investment costs and the cost of capital. Through this, liquidity has a lasting and positive impact on economies. While liquidity across many products remains high in developed markets, many emerging markets suffer from significantly low levels of trading venue liquidity, effectively placing a constraint on economic and market development. We believe that exchanges, regulators, and capital market participants can take action to grow liquidity, improve the efficiency of trading, and better service issuers and investors in their markets. The indirect benefits to emerging market economies could be significant. -

Dubai's Loss Is Saudi's Gain As Βirms Look to Move Listings

The World’s Leading Islamic Finance News Provider (All Cap) Islamic social Surge in Islamic IsDB to US asset managers 1100 1,078.67 1050 ę nance to assume ę nancing invest in target Muslims, 1,058.07 1000 more prominent expected as science and Christians and 950 -1.9% role in Malaysia’s federal cabinet technological Jews with faith- 900 W T F S S M T next ę nancial approves innovations based investment sector blueprint...5 domestic Sukuk to tackle portfolios...6 Powered by: IdealRatings® issuance...5 COVID-19...6 COVER STORY 8th April 2020 (Volume 17 Issue 14) Dubai’s loss is Saudi’s gain as ϐirms look to move listings The delisting of DP World back in comparison, DFM was worth around international investors. And there are February lost NASDAQ Dubai its US$1.1 billion, with 67 companies listed, some who now question whether the most valuable stock, and came as a while ADX came in at US$757 million. size of the local market really requires serious blow to the emirate’s eě orts three exchanges for similar products, to boost liquidity on its domestic DP World decided to delist due to its suggesting that NASDAQ Dubai might exchanges. But while DP World had long-term strategy, which it said was do beĴ er to bow out of the equities sound strategic objectives for its incompatible with the short-term view game altogether and focus on its more departure, IFN has learned that there of the public market, and its emphasis successful segments of Sukuk and could be a groundswell of other ę rms on shareholder returns. -

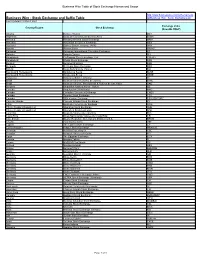

Stock Exchange and Suffix Table Ml/Business Wire Stock Exchanges.Pdf Last Updated 12 March 2021

Business Wire Table of Stock Exchange Names and Usage http://www.businesswire.com/schema/news Business Wire - Stock Exchange and Suffix Table ml/Business_Wire_Stock_Exchanges.pdf Last Updated 12 March 2021 Exchange Value Country/Region Stock Exchange (NewsML ONLY) Albania Bursa e Tiranës BET Argentina Bolsa de Comercio de Buenos Aires BCBA Armenia Nasdaq Armenia Stock Exchange ARM Australia Australian Securities Exchange ASX Australia Sydney Stock Exchange (APX) APX Austria Wiener Börse WBAG Bahamas Bahamas International Securities Exchange BS Bahrain Bahrain Bourse BH Bangladesh Chittagong Stock Exchange, Ltd. CSEBD Bangladesh Dhaka Stock Exchange DSE Belgium Euronext Brussels BSE Bermuda Bermuda Stock Exchange BSX Bolivia Bolsa Boliviana de Valores BO Bosnia and Herzegovina Banjalucka Berza BLSE Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevska Berza SASE Botswana Botswana Stock Exchange BT Brazil Bolsa de Valores do Rio de Janeiro BVRJ Brazil Bolsa de Valores, Mercadorias & Futuros de Sao Paulo SAO Bulgaria Balgarska fondova borsa - Sofiya BB Canada Aequitas NEO Exchange NEO Canada Canadian Securities Exchange CNSX Canada Toronto Stock Exchange TSX Canada TSX Venture Exchange TSX VENTURE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands Stock Exchange KY Chile Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago SGO China, People's Republic of Shanghai Stock Exchange SHH China, People's Republic of Shenzhen Stock Exchange SHZ Colombia Bolsa de Valores de Colombia BVC Costa Rica Bolsa Nacional de Valores de Costa Rica CR Cote d'Ivoire Bourse Regionale Des Valeurs Mobilieres S.A. BRVM Croatia -

MSCI Tadawul 30 Index (USD) (PRICE)

MSCI Tadawul 30 Index (USD) The MSCI Tadawul 30 Index is jointly launched by MSCI and the Saudi Stock Exchange Co. (Tadawul). The Index is based on the MSCI Saudi Arabia IMI Index that represents the performance of large, mid and small-cap stocks of the Saudi Arabia equity market. The Index targets the top 30 securities of the MSCI Saudi Arabia IMI Index based on free float market capitalization with capping criteria and is designed to be able to serve as the basis for financial products including derivatives and ETFs. CUMULATIVE INDEX PERFORMANCE — PRICE RETURNS (USD) ANNUAL PERFORMANCE (%) (MAY 2015 – AUG 2021) MSCI Saudi Year MSCI Tadawul 30 Arabia IMI MSCI Tadawul 30 2020 -1.72 -0.39 MSCI Saudi Arabia IMI 2019 3.62 5.85 150 2018 15.70 12.38 2017 4.08 2.58 2016 7.44 8.59 100 99.84 98.42 50 May 15 Nov 15 Apr 16 Oct 16 Mar 17 Sep 17 Mar 18 Aug 18 Feb 19 Jul 19 Jan 20 Jun 20 Dec 20 INDEX PERFORMANCE — PRICE RETURNS (%) (AUG 31, 2021) FUNDAMENTALS (AUG 31, 2021) ANNUALIZED Since 1 Mo 3 Mo 1 Yr YTD 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr May 29, 2015 Div Yld (%) P/E P/E Fwd P/BV MSCI Tadawul 30 4.48 8.33 43.81 32.03 10.07 13.76 na 4.67 2.03 21.23 19.08 2.73 MSCI Saudi Arabia IMI 3.70 8.03 43.37 31.60 10.99 13.54 na 4.41 1.99 23.21 19.35 2.69 INDEX RISK AND RETURN CHARACTERISTICS (AUG 31, 2021) ANNUALIZED STD DEV (%) 2 MAXIMUM DRAWDOWN Turnover (%) 1 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr (%) Period YYYY-MM-DD MSCI Tadawul 30 9.60 na na na 41.58 2019-05-01—2020-03-16 MSCI Saudi Arabia IMI 7.32 18.81 17.77 na 39.48 2015-05-29—2016-01-21 1 Last 12 months 2 Based on monthly price returns data The MSCI Tadawul 30 Index was launched on Dec 05, 2018. -

List of Asian Stock Exchanges

List of Asian stock exchanges This is a list of Asian stock exchanges. In the Asian region, there are multiple stock exchanges. As per data from World Federation of Exchanges, below are top 10 selected in 2019:[1][2] Tokyo Stock Exchange, Japan Shanghai Stock Exchange, China Hong Kong Stock Exchange, Hong Kong Shenzhen Stock Exchange, China Bombay Stock Exchange, India National Stock Exchange, India Korea Exchange, South Korea Taiwan Exchange, Taiwan Singapore Exchange, Singapore The Stock Exchange of Thailand, Thailand Asia Contents Stock exchanges Central Asian East Asian North Asia South Asian Southeast Asian West Asian See also References External links Stock exchanges Central Asian Operating Economy Exchange Location Founded Listings Link Technology MIC KASE (http Kazakhstan Stock Almaty 1993 127 s://kase.k Exchange z/en/) Kazakhstan Astana AIX (http Nasdaq Nur- International 2018 25 s://www.ai Matching AIXK Sultan Exchange x.kz/) Engine[3] KSE (htt Kyrgyz Stock Bishkek 1994 p://www.ks Kyrgyzstan Exchange (KSE) e.kg/) CASE (http Central Asian s://www.ca Dushanbe 2015 Tajikistan Stock Exchange se.com.tj/e n/) SRCMET State Commodity (https://ww and Raw Material Ashgabat 1994 w.exchang Exchange of Turkmenistan e.gov.tm/?l Turkmenistan ang=en) UZSE (http Tashkent Stock Tashkent 1994 104 s://uzse.u Uzbekistan Exchange z/) East Asian Economy Exchange Location Founded Listings Link Shanghai Stock SSE (http://www.sse.com. Shanghai 1990 Exchange cn) Shenzhen Stock SZSE (http://www.szse.cn/ Shenzhen 1991 2,375 (Jan 2021) Mainland Exchange main/) China Dalian Commodity DCE (http://www.dce.com. Dalian 1993 Exchange cn/DCE/) SEHK (https://web.archive. -

Blockchain Presentation

Nasdaq Blockchain Johan Toll, Product Manager Blockchain December, 2017 NASDAQ A FINTECH COMPANY NASDAQ - WHO WE ARE We don’t chase the opportunities of tomorrow - We create them A financial technology company, rewriting the future of global Market Services economies & markets by unlocking Marketplaces & Associated capital and opportunities through Connectivity our technology, innovation, and 36% of Net Revenues expertise. Market Technology Corporate Market, Regulatory and Information Services Risk solutions Services Listings, Intelligences 12% of Net Revenues Market Data, Index & Communications and Analytics 28% of Net Revenues 24% of Net Revenues 3 AMERICAS (21) MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA (19) • AFFINITY CAPITAL EXCHANGE • ABU DHABI SECURITIES EXCHANGE • BATS EXCHANGE (S) • BAHRAIN BOURSE MARKET TECHNOLOGY • BERMUDA STOCK EXCHANGE • DUBAI FINANCIAL MARKET • BOLSA INSTITUCIONAL DE VALORES • EAST AFRICA EXCHANGE • BM&FBOVESPA (S) • ERBIL STOCK EXCHANGE • BOVESPA MARKET SURVEILLANCE BSM (S) • THE EGYPTIAN EXCHANGE • BOLSA DE VALORES DE COLOMBIA • IRAQ STOCK EXCHANGE • BOLSA ELECTRÓNICA DE CHILE • KUWAIT CMA (S) • BOLSA MEXICANAS DE VALORES (S) • BOURSA KUWAIT POWERING • DEPÓSITO CENTRAL DE VALORES • NASDAQ DUBAI • FINRA • NIGERIAN STOCK EXCHANGE • GOLDMAN SACHS DARK POOL • NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SECURITY DEALERS MORE THAN • ICE US (S) • NIGERIAN CENTRAL SECURITIES CLEARING SYSTEM • IIROC (S) • PALESTINE SECURITIES EXCHANGE • LAT AM SEF (S) • PALESTINE CAPITAL MARKETS AUTHORITY (S) • NEX (BROKERTEC US) • QATAR CSD • NORTH AMERICAN DERIVATIVES -

Market Infrastructures and Market

Market infrastructures and market integrity: A post-crisis journey and a vision for the future Market infrastructures and market integrity: A post-crisis journey and a vision for the future Copyright 2018 Oliver Wyman and World Federation of Exchanges 1 CONTENTS 1 2 THE EVOLVING SUPERVISORY ROLE OF MARKET INTRODUCTION AND INFRASTRUCURE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FIRMS page 2 page 9 3 TRENDS IN FINANCIAL MARKETS AND CHANGES TO THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT page 14 Copyright 2018 Oliver Wyman and World Federation of Exchanges 2 4 5 A VISION FOR THE FUTURE ROLE AND CAPABILITIES OF MARKET INFRASTRUCTURES IN ENSURING ROBUST CONCLUSION MARKET INTEGRITY AND APPENDIX page 28 page 38 Copyright 2018 Oliver Wyman and World Federation of Exchanges 3 1 INTRODUCTION Exchanges and clearinghouses / central counterparties (CCPs), (hereinafter referred to collectively as market infrastructures, or MIs), serve two main functions: 1. Fostering economic growth by enabling the efficient allocation of capital, including providing access to capital (for issuers) and providing avenues for investment and risk management (for investors) 2. Supporting market integrity by (amongst others) strengthening systemic stability, ensuring adherence to transparency obligations by listed companies, and adherence to rules by market participants, and investors Copyright 2018 Oliver Wyman and World Federation of Exchanges 2 The World Federation of Exchanges (WFE) and UNCTAD1 published a report focusing on the first objective in September 2017, titled The Role of Stock Exchanges in Fostering Economic Growth and Sustainable Development. This report focuses on the second purpose – the role of MIs in supporting market integrity. Market integrity is a cornerstone of fair and efficient markets, ensuring that participants enjoy equal access to markets, that price discovery and trading practices are fair, and that high standards of corporate governance are met. -

Tadawul and Dubai Financial Market - a Comparative Study

http://jbar.sciedupress.com Journal of Business Administration Research Vol . 9, No. 2; 2020 Tadawul and Dubai Financial Market - A Comparative Study Issam Tlemsani1, Fai Albadeen2, Ghada Althaaly2, Maha Aljughaiman2 & Hala Bubshait2 1 The Center of International Business, London, United Kingdom 2 Al-Khobar, Dammam, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Issam Tlemsani, The Center of International Business, London, United Kingdom. Received: October 31, 2020 Accepted: November 3, 2020 Online Published: November 4, 2020 doi:10.5430/jbar.v9n2p45 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/jbar.v9n2p45 Abstract This research is intended to identify the fundamentals of stock valuation and utilize them in the macro analysis and micro valuation of two major stock exchanges ‘Tadawul’ and ‘Dubai Financial Market’. These stock exchanges are compared in terms of their strengths and weaknesses according to significant economic indicators, alongside essential stock market determinants, all the while highlighting relevant relationships among them. Upon assessment, GDP has a strong influence on the valuation of the market and KSA’s GDP growth in the last two years has been slightly higher than UAE’s growth, affecting projected GDP growth rates. Tadawul performed better than DFM in P/E ratio indicating a higher willingness to invest in the Saudi stock exchange as well as a higher return expectation. DFM’s stocks are highly undervalued. It can be concluded that both stock exchanges are strong and competitive respectfully, and their potential for growth depends on the economic market that they originate from. Keywords: Tadawul, Dubai financial market, stock valuation, share index 1. Introduction Micro and macro valuation of stock markets is the process of analyzation of existing markets by using qualitative knowledge in the analysis of secondary data provided by the stock market exchange. -

Financial Evaluation of Tadawul All Share Index (TASI) Listed Stocks Using Capital Asset Pricing Model”

“Financial evaluation of Tadawul All Share Index (TASI) listed stocks using Capital Asset Pricing Model” Nisa Vinodkumar https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6867-3637 AUTHORS Hadeel Khalid AlJasser Nisa Vinodkumar and Hadeel Khalid AlJasser (2020). Financial evaluation of ARTICLE INFO Tadawul All Share Index (TASI) listed stocks using Capital Asset Pricing Model. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 17(2), 69-75. doi:10.21511/imfi.17(2).2020.06 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.21511/imfi.17(2).2020.06 RELEASED ON Friday, 15 May 2020 RECEIVED ON Saturday, 30 November 2019 ACCEPTED ON Thursday, 07 May 2020 LICENSE This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License JOURNAL "Investment Management and Financial Innovations" ISSN PRINT 1810-4967 ISSN ONLINE 1812-9358 PUBLISHER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 32 0 4 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Investment Management and Financial Innovations, Volume 17, Issue 2, 2020 Nisa Vinodkumar (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia), Hadeel Khalid AlJasser (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) Financial evaluation BUSINESS PERSPECTIVES LLC “СPС “Business Perspectives” of Tadawul All Share Index Hryhorii Skovoroda lane, 10, Sumy, 40022, Ukraine (TASI) listed stocks using www.businessperspectives.org Capital Asset Pricing Model Abstract The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is strongly committed to stimulating savings culture in the local community by providing financial literacy in financial planning, investments, and budgeting. Inculcating the savings and investment behavior among the people will help materialize one of the elements of Saudi Vision 2030. -

Review of Operations and Financial Condition

5. Financial and Corporate Data >> Review of Operations and Financial Condition Consolidated Statement of Financial Position Consolidated Statement of Income/Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows Economic Data/Market Data Corporate Data Review of Operations and Financial Condition Financial Highlights of FY2019 (IFRS) (JPY mil.) FY2015 FY2016 FY2017 FY2018 FY2019 Operating Revenue 114,776 107,885 120,711 121,134 123,688 Operating Expenses 50,925 50,185 50,902 54,111 58,532 Operating Income 66,271 59,377 71,791 69,535 68,533 Net Income Attributable to Owners of the Partner Company 44,877 42,124 50,484 49,057 47,609 EBITDA 77,791 71,595 82,505 82,568 85,683 Dividends per Share1 (JPY) 50.0 47.0 67.0 70.0 54.0 ROE 18.2% 16.4% 19.0% 17.6% 16.3% Note: 1. The amounts shown reflect the stock split (2 for 1) that became effective on October 1, 2015. The dividend figure for FY2017 includes a commemorative dividend of JPY 10 per share, and the dividend figure for FY2018 includes a special dividend of JPY 15 per share. Average Daily Trading Value/Volume of Main Products FY2015 FY2016 FY2017 FY2018 FY2019 Cash Equities (trading value)1 JPY 3,412.6 billion JPY 2,998.7 billion JPY 3,446.2 billion JPY 3,306.8 billion JPY 3,081.1 billion TOPIX Futures (trading volume) 93, 824 contracts 89,966 contracts 105,287 contracts 103,896 contracts 121,034 contracts Nikkei 225 Futures2 (trading volume) 230,435 contracts 184,250 contracts 200,646 contracts 205,046 contracts 232,821 contracts Nikkei 225 Options3 (trading value) JPY 30.7 billion JPY 24.8 billion JPY 27.0 billion JPY 23.0 billion JPY 26.8 billion 10-year JGB Futures (trading volume) 34,658 contracts 28,569 contracts 35,978 contracts 42,087 contracts 39,640 contracts Notes: 1.