Alternative Global Cretaceous Paleogeography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jane Francis British Antarctic Survey

Pliocene environments on Antarctica from the fossil record Jane Francis British Antarctic Survey J.Francis NASA Fossil plants in Antarctic rocks highlight past warm climates <1% rock but with fossils Seymour Island, Antarctica J.Francis Ron Blakey maps From 100 million years ago (Cretaceous) the Antarctic continent was over the South Pole………… but Antarctica was warm and green Cretaceous petrified tree stumps in their original growth position Alexander Island, Antarctica petrified tree trunk Fossil tree encased in rock strata fossil soil Jodie Howe Fossil pollen, fossil leaves and fossil wood Ferns Fossil Cladophlebis Dicksonia antarctica Monkey Puzzle trees grew in Antarctica J.Francis Araucaria araucana, Monkey Puzzle, growing today in the Chilean Andes Araucaria araucana R. Carpenter 100 million year old forests, Alexander Island Based on PhD work of Jodie Howe & Jane Francis, University of Leeds and BAS geologists. Painted by Rob Nicholls. Housed at BAS Tosolini, Francis, Cantrill Many Antarctic fossil plants are related to plants that live today in South America, Australia and New Zealand - ancient ancestors of Southern Hemisphere vegetation under warm climates Nothofagus Embothrium Brachychiton Cool temp Warm temp Sub-tropical Antarctica 70 million years ago ©James McKay Ross McPhee, American Museum of Natural History Antarctica 50 million years ago (Eocene) – very warm Cooler climates allowed ice sheets to form and glaciers reached the coast by 40 million years ago Reconstruction of Miocene ice sheet, Antarctica. 14-23 my Gasson -

Oceans, Antarctica

G9102 ATLANTIC OCEAN. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G9102 ETC. .G8 Guinea, Gulf of 2950 G9112 NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN. REGIONS, BAYS, ETC. G9112 .B3 Baffin Bay .B34 Baltimore Canyon .B5 Biscay, Bay of .B55 Blake Plateau .B67 Bouma Bank .C3 Canso Bank .C4 Celtic Sea .C5 Channel Tunnel [England and France] .D3 Davis Strait .D4 Denmark Strait .D6 Dover, Strait of .E5 English Channel .F45 Florida, Straits of .F5 Florida-Bahamas Plateau .G4 Georges Bank .G43 Georgia Embayment .G65 Grand Banks of Newfoundland .G7 Great South Channel .G8 Gulf Stream .H2 Halten Bank .I2 Iberian Plain .I7 Irish Sea .L3 Labrador Sea .M3 Maine, Gulf of .M4 Mexico, Gulf of .M53 Mid-Atlantic Bight .M6 Mona Passage .N6 North Sea .N7 Norwegian Sea .R4 Reykjanes Ridge .R6 Rockall Bank .S25 Sabine Bank .S3 Saint George's Channel .S4 Serpent's Mouth .S6 South Atlantic Bight .S8 Stellwagen Bank .T7 Traena Bank 2951 G9122 BERMUDA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G9122 ISLANDS, ETC. .C3 Castle Harbour .C6 Coasts .G7 Great Sound .H3 Harrington Sound .I7 Ireland Island .N6 Nonsuch Island .S2 Saint David's Island .S3 Saint Georges Island .S6 Somerset Island 2952 G9123 BERMUDA. COUNTIES G9123 .D4 Devonshire .H3 Hamilton .P3 Paget .P4 Pembroke .S3 Saint Georges .S4 Sandys .S5 Smiths .S6 Southampton .W3 Warwick 2953 G9124 BERMUDA. CITIES AND TOWNS, ETC. G9124 .H3 Hamilton .S3 Saint George .S6 Somerset 2954 G9132 AZORES. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G9132 ISLANDS, ETC. .A3 Agua de Pau Volcano .C6 Coasts .C65 Corvo Island .F3 Faial Island .F5 Flores Island .F82 Furnas Volcano .G7 Graciosa Island .L3 Lages Field .P5 Pico Island .S2 Santa Maria Island .S3 Sao Jorge Island .S4 Sao Miguel Island .S46 Sete Cidades Volcano .T4 Terceira Island 2955 G9133 AZORES. -

Global Southern Limit of Flowering Plants and Moss Peat Accumulation Peter Convey,1 David W

RESEARCH/REVIEW ARTICLE Global southern limit of flowering plants and moss peat accumulation Peter Convey,1 David W. Hopkins,2,3,4 Stephen J. Roberts1 & Andrew N. Tyler3 1 British Antarctic Survey, National Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 2 Scottish Crop Research Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, UK 3 Environmental Radioactivity Laboratory, School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, UK 4 School of Life Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, Riccarton, Edinburgh EH14 4AS, UK Keywords Abstract Antarctic plants; distribution limits; peat accumulation; dating. The ecosystems of the western Antarctic Peninsula, experiencing amongst the most rapid trends of regional climate warming worldwide, are important ‘‘early Correspondence warning’’ indicators for responses expected in more complex systems else- Peter Convey, British Antarctic Survey, where. Central among responses attributed to this regional warming are National Environment Research Council, widely reported population and range expansions of the two native Antarctic High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge flowering plants, Deschampsia antarctica and Colobanthus quitensis. However, CB3 0ET, UK. E-mail: [email protected] confirmation of the predictions of range expansion requires baseline knowl- edge of species distributions. We report a significant southwards and westwards extension of the known natural distributions of both plant species in this region, along with several range extensions in an unusual moss community, based on a new survey work in a previously unexamined and un-named low altitude peninsula at 69822.0?S71850.7?W in Lazarev Bay, north-west Alexander Island, southern Antarctic Peninsula. These plant species therefore have a significantly larger natural range in the Antarctic than previously thought. -

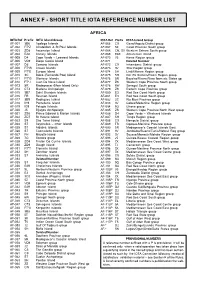

Short Title Iota Reference Number List

RSGB IOTA DIRECTORY ANNEX F - SHORT TITLE IOTA REFERENCE NUMBER LIST AFRICA IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands AF-066 C9 Gaza/Maputo District group AF-002 FT*Z Amsterdam & St Paul Islands AF-067 5Z Coast Province South group AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island AF-068 CN, S0 Western Sahara South group AF-004 EA8 Canary Islands AF-069 EA9 Alhucemas Island AF-005 D4 Cape Verde – Leeward Islands AF-070 V5 Karas Region group AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island AF-071 Deleted Number AF-007 D6 Comoro Islands AF-072 C9 Inhambane District group AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands AF-073 3V Sfax Region group AF-009 FT*E Europa Island AF-074 5H Lindi/Mtwara Region group AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island AF-075 5H Dar Es Salaam/Pwani Region group AF-011 FT*G Glorioso Islands AF-076 5N Bayelsa/Rivers/Akwa Ibom etc States gp AF-012 FT*J Juan De Nova Island AF-077 ZS Western Cape Province South group AF-013 5R Madagascar (Main Island Only) AF-078 6W Senegal South group AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago AF-079 ZS Eastern Cape Province group AF-015 3B7 Saint Brandon Islands AF-080 E3 Red Sea Coast North group AF-016 FR Reunion Island AF-081 E3 Red Sea Coast South group AF-017 3B9 Rodrigues Island AF-082 3C Rio Muni Province group AF-018 IH9 Pantelleria Island AF-083 3V Gabes/Medenine Region group AF-019 IG9 Pelagie Islands AF-084 9G Ghana group AF-020 J5 Bijagos Archipelago AF-085 ZS Western Cape Province North West group AF-021 ZS8 Prince Edward & Marion Islands AF-086 D4 Cape Verde – Windward Islands AF-022 ZD7 -

A Comparison of the Ammonite Faunas of the Antarctic Peninsula and Magallanes Basin

J. geol. Soc. London, Vol. 139, 1982, pp. 763-770, 1 fig, 1 table. Printed in Northern Ireland A comparison of the ammonite faunas of the Antarctic Peninsula and Magallanes Basin M. R. A. Thomson SUMMARY: Ammonite-bearingJurassic and Cretaceous sedimentary successions are well developed in the Antarctic Peninsula and the Magallanes Basin of Patagonia. Faunas of middle Jurassic-late Cretaceous age are present in Antarctica but those of Patagonia range no earlier than late Jurassic. Although the late Jurassic perisphinctid-dominated faunas of the Antarctic Peninsulashow wide-ranging Gondwana affinities, it is not yet possible to effect a close comparison with faunas of similar age in Patagonia because of the latter's poor preservation and our scant knowledge of them. In both regions the Neocomian is not well represented in the ammonite record, although uninterrupted sedimentary successions appear to be present. Lack of correspondence between the Aptian and Albian faunas of Alexander I. and Patagonia may be due to major differences in palaeogeographical setting. Cenomanian-Coniacian ammonite faunas are known only from Patagonia, although bivalve faunas indicate that rocks of this age are present in Antarctica. Kossmaticeratid faunas mark the late Cretaceous in both regions. In Antarcticathese have been classified as Campanian, whereas in Patagonia it is generally accepted, perhaps incorrectly, that these also range into the Maestrichtian. Fossiliferous Jurassic and Cretaceous marine rocks are rize first those of the Antarctic Peninsula and then to well developedin theAntarctic Peninsula, Scotia compare them with those of Patagonia. Comparisons Ridge andPatagonia (Fig. 1A).In Antarcticathese between Antarctic ammonite faunas and other Gond- rocks are distributed along the western and eastern wana areas wereoutlined by Thomson (1981a), and margins of theAntarctic Peninsula, formerly the the faunas of the marginal basin were discussed in magmatic arc from which the sediments were derived. -

Ar Geochronology on a Mid-Eocene Igneous Event on the Barton and Weaver Peninsulas: Implications for the Dynamic Setting of the Antarctic Peninsula

Article Geochemistry 3 Volume 10, Number 12 Geophysics 8 December 2009 GeosystemsG Q12006, doi:10.1029/2009GC002874 G ISSN: 1525-2027 AN ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF THE EARTH SCIENCES Published by AGU and the Geochemical Society Click Here for Full Article An 40Ar/39Ar geochronology on a mid-Eocene igneous event on the Barton and Weaver peninsulas: Implications for the dynamic setting of the Antarctic Peninsula Fei Wang and Xiang-Shen Zheng Paleomagnetism and Geochronology Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China ([email protected]) Jong I. K. Lee and Won Hie Choe Korea Polar Research Institute, KORDI, Songdo Techno Park, 7-50, Incheon 406-840, South Korea Noreen Evans CSIRO Exploration and Mining, 26 Dick Perry Avenue, Kensington, Western Australia 6151, Australia Also at John de Laeter Centre of Mass Spectrometry, Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, Western Australia 6845, Australia Ri-Xiang Zhu Paleomagnetism and Geochronology Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China [1] The genesis of basaltic to andesitic lavas, mafic dikes, and granitoid plutons composing the subaerial cover on the Barton and Weaver peninsulas, Antarctica, is related to arc formation and subduction processes. Precise dating of these polar rocks using conventional 40Ar/39Ar techniques is compromised by the high degree of alteration (with loss on ignition as high as 8%). In order to minimize the alteration effects we have followed a sample preparation process that includes repeated acid leaching, acetone washing, and hand picking, followed by an overnight bake at 250°C. -

Admiralty Bay, King George Island

Measure 14 (2014) Annex Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Managed Area No.1 ADMIRALTY BAY, KING GEORGE ISLAND Introduction Admiralty Bay is located on King George Island, South Shetland Islands, about 125 kilometers from the northern tip of Antarctic Peninsula (Fig. 1). The primary reason for its designation as an Antarctic Specially Managed Area (ASMA) is to protect its outstanding environmental, historical, scientific, and aesthetic values. Admiralty Bay was first visited by sealers and whalers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and relics from these periods still remain. The area is characterized by magnificent glaciated mountainous landscape, varied geological features, rich sea-bird and mammal breeding grounds, diverse marine communities, and terrestrial plant habitats. For nearly four decades coordinated scientific research has been conducted in Admiralty Bay by five different countries. The studies on penguins have been undertaken continuously since 1976, and is the longest ever done in Antarctica. Admiralty Bay also has one of the longest historical series of meteorological data collected for the Antarctic Peninsula, considered as one of the most sensitive areas of the planet to climate change. The Area comprises environments laying within three domains defined in the Environmental Domains Analysis for Antarctica: Environment A – Antarctic Peninsula northern geologic; Environment E – Antarctic Peninsula and Alexander Island main ice fields; and Environment G – Antarctic Peninsula offshore island geologic (Resolution 3 (2008)). Under the Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions (ACBR) classification the Area lies within ACBR 3 – Northwest Antarctic Peninsula (Resolution 6 (2012)). The Area, which includes all the marine and terrestrial areas within the glacial drainage basin of Admiralty Bay, is considered to be sufficiently large to provide adequate protection to the values described below. -

Native Terrestrial Invertebrate Fauna from the Northern Antarctic Peninsula

86 (1) · April 2014 pp. 1–14 Supplementary Material Native terrestrial invertebrate fauna from the northern Antarctic Peninsula: new records, state of current knowledge and ecological preferences – Summary of a German federal study David J. Russell1*, Karin Hohberg1, Mikhail Potapov2, Alexander Bruckner3, Volker Otte1 and Axel Christian 1 Senckenberg Museum of Natural History Görlitz, Postfach 300 154, 02806 Görlitz, Germany 2 Moscow Pedagogical State University, Mnevniki Street, 123308 Moscow, Russia 3 University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Gregor Mendel-Straße 33, 1180 Vienna, Austria * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 27 February 2014 | Accepted 8 March 2014 Published online at www.soil-organisms.de 1 April 2014 | Printed version 15 April 2014 Supplementary Material Table S1. Average values of the substrate parameters of the investigated sites measured in the individual study years. For a statistical analysis and further information, see Russell et al. (2013). Vegetation cover is given as an average of all plots of the categories: 1 = cover up to 25 %, 2 = 25–50 %, 3 = 50–<100 %, 4 = 100 %. For the specific plant societies, see Russell et al. (2013). ‘Organic Material (%)’ represents the mass loss at ignition (500°C for 2 hours). Organic Material Substrate Texture (%) (%) tot org C Jahr cover Vegetation (°C) Temperature Soil (%) Soil Moisture pH Organic Material (%) N Site C/N Coarse Gravel (%) Medium Gravel (%) Fine Gravel (%) Coarse Sand (%) Medium Sand (%) Fine Sand (%) Clay/Silt (%) -

RECYCLED CRETACEOUS BELEMNITES in LOWER MIOCENE GLACIO-MARINE SEDIMENTS (CAPE MELVILLE FORMATION) of KING GEORGE ISLAND, WEST ANTARCTICA (Plates 9-11)

KRZYSZTOF BIRKENMAJER, ANDRZEJ GAZDZICKI, HALINA PUGACZEWSKA and RYSZARD WRONA RECYCLED CRETACEOUS BELEMNITES IN LOWER MIOCENE GLACIO-MARINE SEDIMENTS (CAPE MELVILLE FORMATION) OF KING GEORGE ISLAND, WEST ANTARCTICA (plates 9-11) BIRKENMAJER, K., GAZoZICKI, A., PuOACZEWSKA, H. and WRONA, R.: Recycled Cretaceous belemnites in Lower Miocene glacio-marine sediments (Cape MelviIIe Formation) of King George Island, West Antarctica. Palaeontologia Polonica, 49, 49-62, 1987. FossiIiferous glacio-marine strata of the Cape Melville Formation (Lower Miocene) yielded recycled Cretaceous fossils - coccoliths and belemnites in addition to Tertiary biota. The belemnites here described belong to the family Dimitobelidae WHITEHOUSE, 1924, and are represented by three taxa: Dimitobelus aff. macgregori (GLAESSNER, 1945), D. cf. superstes (HECroR, 1886) and Peratobelus sp, These Cre taceous fossils were brought to King George Island by drifting icebergs during the Lower Miocene Melville Glaciation and redeposited together with other dropstones in outer shelf deposits of the Cape Melville Formation. The provenance of these recycled Cretaceous fossils is unknown: they could have been brought by drifting icebergs either from the area of Alexander Island where Cretaceous strata with analogous belemnites are known, or from another site (or sites) of the Antarctic Peninsula sector. Relative abundance of recycled belemnites and Cretaceous calca reous nannoplankton suggests rather a source situated at a distance less than that between King George Island and Alexander Island (some 1200 km), either under ice-sheet or within the shelf area of the Bransfield Strait. Key words: Cretaceous, belemnites, Dimitobelidae, Lower Miocene, glacio-marine strata, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. K. Birkenmajer, Instytut Nauk Geologicznych, Polska Akademia Nauk, 31-002 Kra kow, Senacka 3, Poland; A. -

Late Jurassic - Early Cretaceous Cephalopods of Eastern Alexander Island, Antarctica

SPECIAL PAPERS IN PALAEONTOLOGY 41 Late Jurassic - early Cretaceous cephalopods of eastern Alexander Island, Antarctica THE PALAEONTOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION PRICE £20 SPECIAL PAPERS IN PALAEONTOLOGY NO. 41 ^j^xl LATE JURASSIC-EARLY CRETACEOUS CEPHALOPODS OF EASTERN ALEXANDER ISLAND, ANTARCTICA BY P. J. HOWLETT with 10 plates and 9 text-figures THE PALAEONTOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION LONDON DECEMBER 1989 CONTENTS ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION PREVIOUS WORK GEOLOGICAL SETTING LOCALITIES SYSTEMATIC PALAEONTOLOGY Ammonoidea Phylloceratida Phyllopachyceras Spath Lytoceratida Pterolytoceras Spath Ammonitida Olcostephanus Neumayr Lemurostephanus Thieuloy Virgatosphinctes Uhlig Lytohoplites Spath Raimondiceras Spath Blandfor dicer as Cossmann Bochianites Lory Coleoidea Belemnopseidae Belemnopsis Bayle Belemnopsis Bayle Parabelemnopsis subgen. nov. Telobelemnopsis subgen. nov. Hibolithes Montfort BIOZONATION Ammonite biozonation Belemnite biozonation CONCLUSIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS REFERENCES ABSTRACT. The Fossil Bluff Group of eastern Alexander Island was deposited in the fore-arc basin of an active magmatic arc, which formed the present-day Antarctic Peninsula. Cephalopods are common throughout the group. Ammonites and belemnites of several localities within the northern half of the outcrop are described, and previously described cephalopods are revised. Nine genera and seventeen species of ammonites (of which Raimondiceras alexandrensis and Blanfordiceras weaveri are new), and two genera and sixteen species of belemnites (including two new subgenera: Belemnopsis {Parabelemnopsis) and B. (Telobelemnopsis), and four new species: B. {Belemnopsis) launceloti, B. (T.) rymilli, B. (T.) bertrami and B. (T.) stephensoni) are described. This detailed study of the cephalopods indicates that the Fossil Bluff Group ranges in age from Kimmeridgian (late Jurassic) to at least Aptian (early Cretaceous), and enables seven ammonite biozones and three belemnite biozones (including two sub-biozones) to be erected within the group. -

Your Cruise Expedition to Charcot & Peter I Islands

Expedition to Charcot & Peter I Islands - Christmas Cruise From 12/14/2021 From Punta Arenas Ship: LE COMMANDANT CHARCOT to 12/28/2021 to Punta Arenas Landing on Peter I Island is like landing on the moon! This image illustrates how extremely difficult it is to access this small volcanic island located in the Bellingshausen Sea 450 km (280 miles) from the Antarctic coasts, on which only a rare few people have set foot, like the astronauts on the surface of the moon. Discovered in February 1821, Peter I Island could only be approached for the first time in 1929, as the ice front made approach and disembarkation difficult. Its summit still remains untouched to this day. This unusual itinerary will also provide an opportunity to approach Charcot Island, thus named by Captain Charcot in memory of his father during its discovery in 1910. We are privileged guests in these extreme lands where we are at the mercy of weather and ice conditions. Our navigation will be determined by the type of ice we come across; as the Overnight in Santiago + flight Santiago/Punta Arenas coastal ice must be preserved, we will take this factor into account from day to day in our + transfers + flight Punta Arenas/Santiago itineraries. The sailing schedule and any landings, activities and wildlife encounters are subject to weather and ice conditions. These experiences are unique and vary with each departure. The Captain and the Expedition Leader will make every effort to ensure that your experience is as rich as possible, while respecting safety instructions and regulations imposed by the IAATO. -

Mesozoic–Cainozoic

Geosciences 2013, 3, 331-353; doi:10.3390/geosciences3020331 OPEN ACCESS geosciences ISSN 2076-3263 www.mdpi.com/journal/geosciences Article Geodynamic Reconstructions of the Australides—2: Mesozoic–Cainozoic Christian Vérard and Gérard M. Stampfli * Institute of Earth Science, University of Lausanne, Géopolis, Quartier Mouline, Lausanne CH–1015, Switzerland; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-21-692-4306; Fax: +41-21-692-4305. Received: 23 March 2013; in revised form: 29 April 2013/ Accepted: 13 May 2013/ Published: 4 June 2013 Abstract: The present work, derived from a full global geodynamic reconstruction model over 600 Ma and based on a large database, focuses herein on the interaction between the Pacific, Australian and Antarctic plates since 200 Ma, and proposes integrated solutions for a coherent, physically consistent scenario. The evolution of the Australia–Antarctica–West Pacific plate system is dependent on the Gondwana fit chosen for the reconstruction. Our fit, as defined for the latest Triassic, implies an original scenario for the evolution of the region, in particular for the “early” opening history of the Tasman Sea. The interaction with the Pacific, moreover, is characterised by many magmatic arc migrations and ocean openings, which are stopped by arc–arc collision, arc–spreading axis collision, or arc–oceanic plateau collision, and subduction reversals. Mid-Pacific oceanic plateaus created in the model are much wider than they are on present-day maps, and although they were subducted to a large extent, they were able to stop subduction. We also suggest that adduction processes (i.e., re-emergence of subducted material) may have played an important role, in particular along the plate limit now represented by the Alpine Fault in New Zealand.