Building Resilience in Cities Under Stress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Study on Skills for Employability in South Asia

2012 INNOVATIVE SECONDARY EDUCATION FOR SKILLS ENHANCEMENT (ISESE) Skills for Employability: South Asia August 8, 2012 Skills for Employability: South Asia Prepared by: Dr. Aarti Srivastava Department of Foundations of Education Prof. Mona Khare Department of Educational Planning National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA) New Delhi, India TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 2 Section I: Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section II: Setting the Stage for Skills and Employability .......................................................................... 9 Section III: Signals from the Employers .................................................................................................... 19 Section IV: Summary and Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 50 References ............................................................................................................................................. 53 Annexes ................................................................................................................................................. 56 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Education is both a cause and consequence of development. It is essentially seen as an aid to individual’s economic -

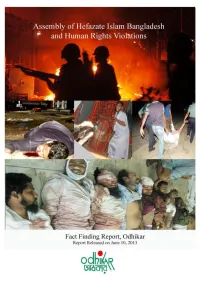

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 019 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study Agunbiade, Elijah Muyiwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji University of Lagos, Nigeria August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Elijah Muyiwa Agunbiade University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] or [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Agunbiade, E. M. and Olajide, O. A. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 019, Nairobi, Kenya. ©Partnership for African Social & Governance Research, 2016 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.pasgr.org ISBN 978‐9966‐087‐15‐7 Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ -

Periodical Report Periodical Report

ICTICT IncideIncidentsnts DatabaseDatabase PeriodicalPeriodical ReportReport January 2012 2011 The following is a summary and analysis of terrorist attacks and counter-terrorism operations that occurred during the month of January 2012, researched and recorded by the ICT database team. Among others: Irfan Ul Haq, 37 was sentenced to 50 months in prison on 5 January, for providing false documentation and attempting to smuggle a suspected Taliban member into the USA. On 5 January, Eyad Rashid Abu Arja, 47, a male Palestinian with dual Australian-Jordanian nationality, was sentenced to 30 months in prison in Israel for aiding Hamas. On 6 January, a bomb exploded in Damascus, Syria killing 26 people and wounding 63 others. ETA militant Andoni Zengotitabengoa, was sentenced on 6 January to 12 years in prison for the illegal possession of weapons, as well car theft, falsification of documents, assault and resisting arrest. On 9 January, Sami Osmakac, 25, was charged with plotting to attack crowded locations in Florida, USA. On 10 January, a car bomb exploded at a bus stand outside a shopping bazaar in Jamrud, northwestern Pakistan killing 26 people and injuring 72. Jermaine Grant, 29, a British man and three Kenyans were charged on 13 January in Mombasa, Kenya with possession of bomb-making materials and plotting to explode a bomb. On 13 January Thai police arrested Hussein Atris, 47, a Lebanese-Swedish man, who was suspected of having links to Hizballah. He was charged three days later with the illegal possession of explosive materials. On 14 January, a suicide bomber, disguised in a military uniform, killed 61 people and injured 139, at a checkpoint outside Basra, Iraq. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Primary Education Finance for Equity and Quality an Analysis of Past Success and Future Options in Bangladesh

WORKING PAPER 3 | SEPTEMBER 2014 BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES PRIMARY EDUCATION FINANCE FOR EQUITY AND QUALITY AN ANALYSIS OF PAST SUCCESS AND FUTURE OPTIONS IN BANGLADESH LIESBET STEER, FAZLE RABBANI AND ADAM PARKER Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES This working paper series is dedicated to the memory of Brooke Shearer (1950-2009), a loyal friend of the Brookings Institution and a respected journalist, government official and non-governmental leader. This series focuses on global poverty and development issues related to Brooke Shearer’s work, including: women’s empowerment, reconstruction in Afghanistan, HIV/AIDS education and health in developing countries. Global Economy and Development at Brookings is honored to carry this working paper series in her name. Liesbet Steer is a fellow at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Fazle Rabbani is an education adviser at the Department for International Development in Bangladesh. Adam Parker is a research assistant at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the many people who have helped shape this paper at various stages of the research process. We are grateful to Kevin Watkins, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the executive director of the Overseas Development Institute, for initiating this paper, building on his earlier research on Kenya. Both studies are part of a larger work program on equity and education financing in these and other countries at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Selim Raihan and his team at Dhaka University provided the updated methodology for the EDI analysis that was used in this paper. -

(Bangladesh) (PDF

PARTICIPANTS’111TH INTERNATIONAL PAPERS SEMINAR PARTICIPANTS’ PAPERS THE ROLE OF POLICE, PROSECUTION AND THE JUDICIARY IN THE CHANGING SOCIETY Rebeka Sultana* I. INTRODUCTION resentment due to uneven economic prosperity; unstable public order Crime prevention means the elimination intensified by feud, illiteracy, of criminal activity before it occurs. unemployment etc, as the fundamental Prevention of crime is being effected/ causes of the high escalation of crime in enforced with the help of preventive Bangladesh. prosecution, arrest, surveillance of bad characters etc by the law enforcing Due to radical changes taking place in agencies of the country concerned. Crime, the livelihood of people in the recent past, and the control of crime throughout the criminals have also brought remarkable world, has been changing its features changes in their style of operation in rapidly. Critical conditions are taking place committing crimes. The crime preventive/ when there is change. Nowdays, causes of prosecution systems are not equipped crime are more complex and criminals are accordingly. As the existing prosecution becoming more sophisticated. With the cannot render appropriate support to the increase of social sensitivity to crime, more law enforcing agencies in controlling and more a changing social attitude, crimes, the criminals are indulged and particularly towards the responsibility of consequently, crime trends increase in the citizenry to law enforcement, arises. society. Besides, due to insufficient Existing legal systems and preventative preventive intelligence, crime prevention, measures for controling crime have to be particularly preventive prosecution, does changed correspondingly. There should be not achieve much. an attempt to devise the ways and means to equip the older system of crime It has been noticed that the younger prevention and criminal justice to face generation in this part of the world is being these new challenges. -

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Bangladesh April 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.7 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.3 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 - 4.45 Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 4.1 - 4.4 1972 –1982 4.5 - 4.8 1983 – 1990 4.9 - 4.14 1991 – 1999 4.15 - 4.26 2000 – the present 4.27 - 4.45 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.51 The constitution 5.1 - 5.3 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 - 5.6 Political System 5.7 - 5.13 Judiciary 5.14 - 5.21 Legal Rights /Detention 5.22 - 5.30 - Death Penalty 5.31 – 5.32 Internal Security 5.33 - 5.34 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.35 – 5.37 Military Service 5.38 Medical Services 5.39 - 5.45 Educational System 5.46 – 5.51 6. Human Rights 6.1- 6.107 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.53 Overview 6.1 - 6.5 Torture 6.6 - 6.7 Politically-motivated Detentions 6.8 - 6.9 Police and Army Accountability 6.10 - 6.13 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.14 – 6.23 Freedom of Religion 6.24 - 6.29 Hindus 6.30 – 6.35 Ahmadis 6.36 – 6.39 Christians 6.40 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.41 Employment Rights 6.42 - 6.47 People Trafficking 6.48 - 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 - 6.52 Authentication of Documents 6.53 6.B Human Rights – Specific Groups 6.54 – 6.85 Ethnic Groups Biharis 6.54 - 6.60 The Tribals of the Chittagong Hill Tracts 6.61 - 6.64 Rohingyas 6.65 – 6.66 Women 6.67 - 6.71 Rape 6.72 - 6.73 Acid Attacks 6.74 Children 6.75 - 6.80 - Child Care Arrangements 6.81 – 6.84 Homosexuals 6.85 Bangladesh April 2004 6.C Human Rights – Other Issues 6.86 – 6.89 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 6.86 - 6.89 Annex A: Chronology of Events Annex B: Political Organisations Annex C: Prominent People Annex D: References to Source Material Bangladesh April 2004 1. -

A Study on Characterization & Treatment of Laundry Effluent

IJIRST –International Journal for Innovative Research in Science & Technology| Volume 4 | Issue 1 | June 2017 ISSN (online): 2349-6010 A Study on Characterization & Treatment of Laundry Effluent Prof Dr K N Sheth Mittal Patel Director Assistant Professor Geetanjali Institute of Technical Studies, Udaipur SVBIT, Gandhi Nagar (Gujarat) Mrunali D Desai Assistant Professor Department of Environmental Engineering ISTAR, Vallabh Vdyanagar (Gujarat) Abstract It is a substantial fact that specific disposal standard for laundry effluent have not been prescribed by Gujarat pollution Control Board (GPCB). Laundry waste uses soap, soda, detergents and other chemicals for removal of stains, oil, grease and dirt from the soil clothing. The laundry waste is originated in the residential zone on account of manual cleaning, cleaning by domestic washing machines as well as large amount of effluents are generated by commercial washing including dry-cleaning. An attempt has been made in the present investigation to generalize the characteristics of laundry effluent generated by various sources in Vadodara (Gujarat). It has been found during the laboratory studies, that SS, BOD and COD of laundry waste are high. Treatability studies were carried out in the environmental engineering laboratory of B.V.M. Engineering College, V.V.Nagar for removal of these contaminants. The coagulation-flocculation followed by dual media filtration was found to be most suitable sequence of the treatment. Keywords: Laundry effluent, soil clothing, coagulation-flocculation, dual media filtration _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION Laundry industry is a service industry, In other words, laundry industry is not a manufacturing industry. [1] The State Pollution Control Board has, therefore, not framed standards for specific contaminant levels for the disposal of Laundry waste. -

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Consulate General in Mumbai. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in India. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s India-specific webpage for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses most of India at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime and terrorism. Some areas have increased risk: do not travel to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (except the eastern Ladakh region and its capital, Leh) due to terrorism and civil unrest; and do not travel to within ten kilometers of the border with Pakistan due to the potential for armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System Overall Crime and Safety Situation The Consulate represents the United States in Western India, including the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Goa. Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Mumbai as being a MEDIUM-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government. Although it is a city with an estimated population of more than 25 million people, Mumbai remains relatively safe for expatriates. Being involved in a traffic accident remains more probable than being a victim of a crime, provided you practice good personal security. -

Oral Hygiene Awareness and Practices Among a Sample of Primary School Children in Rural Bangladesh

dentistry journal Article Oral Hygiene Awareness and Practices among a Sample of Primary School Children in Rural Bangladesh Md. Al-Amin Bhuiyan 1,*, Humayra Binte Anwar 2, Rezwana Binte Anwar 3, Mir Nowazesh Ali 3 and Priyanka Agrawal 4 1 Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB), House B162, Road 23, New DOHS, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1206, Bangladesh 2 BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, 68 Shahid Tajuddin Ahmed Sharani, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh; [email protected] 3 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) Shahbag, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh; [email protected] (R.B.A.); [email protected] (M.N.A.) 4 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +880-2-58814988; Fax: +880-2-58814964 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 14 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: Inadequate oral health knowledge and awareness is more likely to cause oral diseases among all age groups, including children. Reports about the oral health awareness and oral hygiene practices of children in Bangladesh are insufficient. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the oral health awareness and practices of junior school children in Mathbaria upazila of Pirojpur District, Bangladesh. The study covered 150 children aged 5 to 12 years of age from three primary schools. The study reveals that the students have limited awareness about oral health and poor knowledge of oral hygiene habits. Oral health awareness and hygiene practices amongst the school going children was found to be very poor and create a much-needed niche for implementing school-based oral health awareness and education projects/programs. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL