J% ^.,^,Su;^ 1 SUPREME Cflhri. 0Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 OHSAA Baseball State Tournament June 1-3 at Huntington Park, Columbus Approved Media List As of Wed., May 31, 11 A.M

2017 OHSAA Baseball State Tournament June 1-3 at Huntington Park, Columbus Approved Media List as of Wed., May 31, 11 a.m. * Media are asked to email spelling corrections to [email protected] * All approved media applicants will receive a confirmation email with instructions including parking, credential pick-up location, media work space, etc. Media Outlet Name Akron Beacon Journal Jarrod Ulrey Akron Beacon Journal Jeff Deckerd Akron Beacon Journal Leah Klefczynski Bellville Clear Fork HS George Fenner Berlin Hiland HS Paul Miller Celina Daily Standard Gary Rasberry Celina Daily Standard Colin Foster Celina Daily Standard Nick Wenning Celina Daily Standard Mark Pummell Celina WCSM Radio Sue Brunswick Celina WCSM Radio Ron Brunswick Cin. Hills Christian Acad. Tammy Rosenfeldt Cincinnati Enquirer Adam Baum Cincinnati Enquirer Kareem Elgazzar Cincinnati Enquirer Sam Greene Cincinnati Enquirer Alex Vehr Cincinnati Enquirer Jim Owens Cincinnati Enquirer Geoff Blankenship Cincinnati Enquirer Matt Blankenship Cincinnati WCPO Tony Tribble Cincinnati WCPO Keenan Singleton Cincinnati WCPO Philip Lee Cincinnati WKRC-TV Local 12 Matthew Alexander Cincinnati WKRC-TV Local 12 Jed DeMuesy Cincinnati WLWT-TV Samantha Mattlin Cincinnati WLWT-TV Mark Slaughter Cincinnati WXIX-TV Joe Danneman Cincinnati WXIX-TV Jeremy Rauch Cincinnati WXIX-TV Adam King Cleveland.com Tim Bielik Cleveland.com Joshua Gunter Cleveland.com John Kuntz Columbus ThisWeek Community News Scott Hennen Columbus WSYX, WTTE-TV Clay Hall Columbus WSYX, WTTE-TV Mike Jones Columbus -

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 18-782 Released: July 27, 2018 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS FILED FOR THE TRANSFER OF CONTROL AND ASSIGNMENT OF BROADCAST TELEVISION LICENSES FROM RAYCOM MEDIA, INC. TO GRAY TELEVISION, INC., INCLUDING TOP-FOUR SHOWINGS IN TWO MARKETS, AND DESIGNATES PROCEEDING AS PERMIT-BUT-DISCLOSE FOR EX PARTE PURPOSES MB Docket No. 18-230 Petition to Deny Date: August 27, 2018 Opposition Date: September 11, 2018 Reply Date: September 21, 2018 On July 27, 2018, the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) accepted for filing applications seeking consent to the assignment of certain broadcast licenses held by subsidiaries of Raycom Media, Inc. (Raycom) to a subsidiary of Gray Television, Inc. (Gray) (jointly, the Applicants), and to the transfer of control of subsidiaries of Raycom holding broadcast licenses to Gray.1 In the proposed transaction, pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger dated June 23, 2018, Gray would acquire Raycom through a merger of East Future Group, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray, into Raycom, with Raycom surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray. Immediately following consummation of the merger, some of the Raycom licensee subsidiaries would be merged into Gray Television Licensee, LLC (GTL), with GTL as the surviving entity. The jointly filed applications are listed in the Attachment to this Public -

1 Curriculum Vitae Philip Matthew Stinson, Sr. 232

CURRICULUM VITAE PHILIP MATTHEW STINSON, SR. 232 Health & Human Services Building Criminal Justice Program Department of Human Services College of Health & Human Services Bowling Green State University Bowling Green, Ohio 43403-0147 419-372-0373 [email protected] I. Academic Degrees Ph.D., 2009 Department of Criminology College of Health & Human Services Indiana University of Pennsylvania Indiana, PA Dissertation Title: Police Crime: A Newsmaking Criminology Study of Sworn Law Enforcement Officers Arrested, 2005-2007 Dissertation Chair: Daniel Lee, Ph.D. M.S., 2005 Department of Criminal Justice College of Business and Public Affairs West Chester University of Pennsylvania West Chester, PA Thesis Title: Determining the Prevalence of Mental Health Needs in the Juvenile Justice System at Intake: A MAYSI-2 Comparison of Non- Detained and Detained Youth Thesis Chair: Brian F. O'Neill, Ph.D. J.D., 1992 David A. Clarke School of Law University of the District of Columbia Washington, DC B.S., 1986 Department of Public & International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences George Mason University Fairfax, VA A.A.S., 1984 Administration of Justice Program Northern Virginia Community College Annandale, VA 1 II. Academic Positions Professor, 2019-present (tenured) Associate Professor, 2015-2019 (tenured) Assistant Professor, 2009-2015 (tenure track) Criminal Justice Program, Department of Human Services Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH Assistant Professor, 2008-2009 (non-tenure track) Department of Criminology Indiana University of -

WHIO-TV, 7, Dam OH +WRGT-TV, 45, Dayton, OH

Federal CommunicationsCommission FCC 05-24 Lucas WTOL-TV, 1 1, Toledo, OH WG,13, Toledo, OH (formerly WSPD) WNWO-TV, 24, Toledo, OH (fOrmery WD") +WW,36, Toledo, OH WIBK, 2, Detroit, MI WxyZ-Tv, 7, Moi, MIt +WKBD-TV, 50, Detroit, MI MdWI WCMH-TV, 4, Columbus, OH (formerly WWC) WSYX, 6, Columbus, OH (formerly WTVN) WBNS-TV, 10, Columbus, OH +WTTE, 28, Columbus, OH +WRGT-TV, 45, DaytoR OH Mahoning WFMJ-TV, 21, YoCmgstown, OH WKBN-TV, 21, Youngstown, OH WYTV, 33, YoungstowR OH +WOW, 19, Shaker Haghtq OH Marion WCMH-TV, 4, Columbus, OH (formerly WLWC) WSYX, 6, Columbus, OH (formerly WTVN) WBNSTV. 10, Columbus, OH +WTE, 28, Columbus, OH Medina XYC-TV, 3, Cleveland, OH WEWS-TV, 5, Cleveland, OH WJW, 8, Cleveland, OH +WOIO, 19, Shakcr Heights, OH WAB, 43, LOGUILOH WKBF-TV, 61, Cleveland, OH Mags WSAZ-TV, 3, Huntm%on, WV WCHSTV, 8, Charleston, wv WOWK-TV, 13, Huntington, WV (f-ly WIITN) +WVAH-TV, 11, charlffton,WV (formerly ch. 23) MerClX WDTN, 2, Dayton, OH (fOrmery mm) WHIO-TV, 7, Dam OH +WRGT-TV, 45, Dayton, OH WANE-TV, 15, Fort Wayne, IN WPTA, 21, Fort Wayne, IN WG-TV, 33, Fort Wayne, IN +W-TV, 55, Fm Wayne, IN WIMA, 35, bma, OH (formerly "MA) +WTL.W, 44, Lima, OH 319 Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-24 Miami WDTN,2, Dayton, OH (formerly WLWD) WHIO-TV, 7, Dayton, OH WPTD, 16, Dayton, OH (formerly WKTR) WKEF, 22, Dayton, OH +WRGT-TV, 45, Dayton, OH MONm WTRF-TV, 7, Wheeling, WV WTOV-TV, 9, Steubenville, OH (formerly WSTV) WDTV, 5, Clarksburg, WV WTAE-TV, 4, Pittsburgh, PA Montgomeq WDTN, 2, Dayton, OH (formerly WLWD) WHIO-TV, 7, Dayton, -

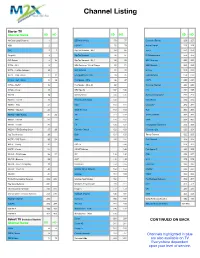

New Channel Lineup

Channel Listing Starter TV Channel Name SD HD SD HD SD HD McClure Local Channel 1 ESPN University 76 77 Discovery Family 226 227 HSN 2 ESPN 2 78 79 Animal Planet 228 229 QVC 3 7 Big Ten Network - Alt 2 84 85 TruTV 252 253 ShopHQ 4 Big Ten Network 86 87 E! Entertainment 254 255 CW-Toledo 5 15 Big Ten Network - Alt 1 88 89 BBC America 260 261 WTOL - Grit 9 NFL Redzone * Extra Charge 90 91 A&E Network 262 263 WTOL - Justice Network 10 NFL Network 92 93 History 268 269 WTOL - CBS Toledo 11 12 Fox SportsTime Ohio 94 95 Food Network 278 279 WTVG - ABC Toledo 13 14 Fox Sports - Ohio 96 97 HGTV 280 281 WTVG - MeTV 16 Fox Sports - Ohio Alt 98 Cooking Channel 282 283 WTVG - Circle 17 NBC Sports 102 103 DIY 284 285 WNHO 19 MLB Network 104 105 National Geographic 292 293 WNWO - Comet 20 Paramount Network 108 MotorTrend 294 295 WNWO - TBD 21 USA 110 111 Discovery 296 297 WNWO - Stadium 22 WGN America 112 113 TLC 300 301 WNWO - NBC Toledo 24 23 TNT 114 115 Travel Channel 302 303 WBGU - Encore 25 TBS 116 117 OWN 304 305 WBGU - Create 26 FX 120 121 Investigation Discovery 308 309 WBGU - PBS Bowling Green 27 28 Comedy Central 122 123 Discovery Life 320 321 You Too America 29 Syfy 124 125 Tennis Channel 322 323 WGTE - PBS Toledo 30 31 Bravo 130 131 Golf Channel 324 325 WGTE - Family 32 AXS TV 144 FXX 328 329 WGTE - Create 33 HDNET Movies 145 Fox Sports 1 332 333 WUPW - FOX Toledo 36 37 IFC 146 147 CNN 376 377 WUPW - Bounce 38 AMC 148 149 HLN 378 379 WUPW - Court TV Mystery 39 Sundance 154 155 Fox News 384 385 WUPW - Court TV 40 Lifetime Movie Network 162 -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

FCC), October 14-31, 2019

Description of document: All Broadcasting and Mass Media Informal Complaints received by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), October 14-31, 2019 Requested date: 01-November-2019 Release date: 26-November-2019-2019 Posted date: 27-July-2020 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, S.W., Room 1-A836 Washington, D.C. 20554 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 tfltJ:J November 26, 2019 FOIA Nos. -

List of Directv Channels (United States)

List of DirecTV channels (United States) Below is a numerical representation of the current DirecTV national channel lineup in the United States. Some channels have both east and west feeds, airing the same programming with a three-hour delay on the latter feed, creating a backup for those who missed their shows. The three-hour delay also represents the time zone difference between Eastern (UTC -5/-4) and Pacific (UTC -8/-7). All channels are the East Coast feed if not specified. High definition Most high-definition (HDTV) and foreign-language channels may require a certain satellite dish or set-top box. Additionally, the same channel number is listed for both the standard-definition (SD) channel and the high-definition (HD) channel, such as 202 for both CNN and CNN HD. DirecTV HD receivers can tune to each channel separately. This is required since programming may be different on the SD and HD versions of the channels; while at times the programming may be simulcast with the same programming on both SD and HD channels. Part time regional sports networks and out of market sports packages will be listed as ###-1. Older MPEG-2 HD receivers will no longer receive the HD programming. Special channels In addition to the channels listed below, DirecTV occasionally uses temporary channels for various purposes, such as emergency updates (e.g. Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike information in September 2008, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011), and news of legislation that could affect subscribers. The News Mix channels (102 and 352) have special versions during special events such as the 2008 United States Presidential Election night coverage and during the Inauguration of Barack Obama. -

Channel Name Channel # Classic Arts Showcase 50-1 WGGN

Cable Co-op is the ONLY subscriber owned, community oriented, non-profit Internet & Cable TV company in Ohio Channel Name Channel # Channel Name Channel # Classic Arts Showcase 50-1 Charge! 55-6 WGGN (Inspirational) Sandusky 50-2 WOIO (CBS) Cleveland HD 55-12 NASA TV HD 50-3 MeTV 55-13 Universal Kids 51-1 ION Cleveland HD 56-3 QVC HD 51-2 Grit 56-4 Oberlin Community Channel 51-3 Mystery 56-5 Local Dashboard 51-4 QVC OTA 56-7 Oberlin City Schools 51-5 Defy TV 56-8 C-Span 51-6 Court TV 56-9 C-Span 2 51-7 WEAO / WNEO HD 56-13 Weather Channel 51-8 WEAD (Fusion) 56-14 LCCC 51-9 WEAD World HD 56-15 Trinity Broadcast Network 51-10 TCT 56-16 WKYC TV (NBC) Cleveland HD 52-1 Justice / True Crimes 52-2 COZI 52-3 Quest 52-4 WEWS TV (ABC) Cleveland HD 52-13 Grit 52-14 Laff 52-15 True/Real 52-16 WQHS (Univision) Cleveland HD 53-1 UniMas HD 53-2 Get TV 53-3 Mystery 53-4 WUAB (My 43) Cleveland HD 53-13 Bounce 53-14 Grit 53-15 Circle TV 53-16 WBNX (The CW) Cleveland HD 54-3 WBNX 2 (The Happy Channel) 54-4 Movies! 54-5 Heroes & Icons HD 54-6 Start TV 54-7 Decades 54-8 WVIZ (PBS) Cleveland HD 54-13 PBS Ohio 54-14 PBS World HD 54-15 PBS Create 54-16 PBS KIDS 54-17 Game Show Network 55-2 WJW (Fox 8) Cleveland HD 55-3 Antenna TV 55-4 Comet 55-5 Cable Co-op is the ONLY subscriber owned, community oriented, non-profit Internet & Cable TV company in Ohio Cable Co-op is the ONLY subscriber owned, community oriented, non-profit Internet & Cable TV company in Ohio Channel Name Channel # Channel Name Channel # Universal Kids 2 TCT 47 WKYC TV (NBC) Cleveland HD 3 -

Jacqueline Demate

JACQUELINE DEMATE Professional Experience WOIO-WUAB, Cleveland Ohio January 2016 – Present Morning Producer June 2018 – Present • Produce competitive morning newscasts daily • Format and write newscasts • Direct morning live reporters and coverage strategies Weekend Producer October 2016 – June 2018 • Produced 9:00 p.m. newscasts on sister station WUAB • Directed weekend reporters and developed story ideas • Produced breaking news and live-streamed event coverage • Field produced live shots, on-the road newscasts and special events Associate Producer January 2016 – October 2016 • As A.P. produced Cleveland 19’s (WOIO) Sunday morning newscast • Brought stability to newscast team and improved ratings week by week • Reformatted newscast and added segments promoting nutrition, local businesses, local animal shelters and entertainment concerts and events MSNBC, New York, New York September 2015 – December 2015 News Student Internship • Wrote scripts daily for MSNBC Live with Jose Diaz-Balart • Assisted producers with research for segments’ elements • Wrote headlines and banners for broadcast and online stories • Attended content meetings and pitched story ideas WOIO-WUAB, Cleveland Ohio June 2015 – August 2015 News Producing Student Internship • Field-produced multiple stories for Emmy nominated series “Romona’s Kids” • Wrote scripts daily for newscasts • Assisted reporters with research and in the field Special Skills • ENPS; iNews; Core, Edius and Premiere Pro editing; Microsoft Office; Luci graphics Special Events and Activities • Estonia, Journalism Study Abroad 2014 • Ireland, Journalism Study Abroad 2015 • Induction, National Society for Leadership and Success, 2015 Education Kent State University, Kent, Ohio • Bachelor of Science, School of Journalism and Mass Communication • Magazine Journalism, Major | Fashion Media, Minor Representation JOHN BUTTE & ASSOCIATES 7903 Driftwood Drive; Geneva, Ohio 44041 216 650 2258 [email protected] | www.johnbutte.com . -

OHV Deaths Report

# Decedent Name News Source Reporter News Headline Hyperlink 1 Williquette Green Bay Press Gazette.com Kent Tumpus Oconto man dies in ATV crash Jan. 22 https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/local/oconto-county/2021/02/02/oconto-county-sheriff-man-dies-atv-accident/4340507001/ 2 Woolverton Idaho News.com News Staff 23-yr-old man killed in UTV crash in northern Idaho https://idahonews.com/news/local/23-year-old-man-killed-in-atv-crash-in-northern-idaho 3 Townsend KAIT 8.com News Staff 2 killed, 3 injured in UTV crash https://www.kait8.com/2021/01/25/killed-injured-atv-crash/ 4 Vazquez KAIT 8.com News Staff 2 killed, 3 injured in UTV crash https://www.kait8.com/2021/01/25/killed-injured-atv-crash/ 5 Taylor The Ada News.com News Staff Stonewall woman killed in UTV accident https://www.theadanews.com/news/local_news/stonewall-woman-killed-in-utv-accident/article_06c3c5ab-f8f6-5f2d-bf78-40d8e9dd4b9b.html 6 Unknown The Southern.com Marily Halstead Body of 39-yr-old man recovered from Ohio River https://thesouthern.com/news/local/body-of-39-year-old-man-recovered-from-ohio-river-after-atv-entered-water-saturday/article_612d6d00-b8ac-5bdc-8089-09f20493aea9.html 7 Hemmersbach LaCrosse Tribune.com News Staff Rural Hillsboro man dies in ATV crash https://lacrossetribune.com/community/vernonbroadcaster/news/update-rural-hillsboro-man-dies-in-atv-crash/article_3f9651b1-28de-5e50-9d98-e8cf73b44280.html 8 Hathaway Wood TV.com News Staff Man killed in UTV crash in Branch County https://www.woodtv.com/news/southwest-michigan/man-killed-in-utv-crash-in-branch-county/ -

Raycom Media Inc

RAYCOM MEDIA INC 175 198 194 195 170 197 128 201 180 DR. OZ 3RD QUEEN QUEEN SEINFELD 4TH SEINFELD 5TH TIL DEATH 1ST DR. OZ CYCLE LATIFAH LATIFAH CYCLE CYCLE KING 2nd Cycle KING 3rd Cycle CYCLE RANK MARKET %US STATION 2011-2014 2014-2015 2013-2014 2014-2015 4th Cycle 5th Cycle 2nd Cycle 3rd Cycle 2013-2014 19 CLEVELAND OH 1.28% WOIO/WUAB WEWS WJW WOIO/WUAB WKYC WJW WJW WOIO/WUAB WBNX WBNX 25 CHARLOTTE NC 1.00% WBTV WAXN/WSOC WJZY/WMYT WBTV WAXN/WSOC WJZY/WMYT WJZY/WMYT WJZY/WMYT 35 CINCINNATI OH 0.78% WXIX WLWT WLWT WLWT WKRC/WSTR EKRC/WKRC EKRC/WKRC/WSTR WXIX WXIX WXIX 38 WEST PALM BEACH-FT PIERCE FL 0.70% WFLX WPBF WPBF WPTV WPTV WFLX WFLX WTCN/WTVX WFLX 44 BIRMINGHAM (ANNISTON-TUSCALOOSA) AL 0.62% WBRC WBMA WBMA WBRC WBRC WABM/WTTO WABM/WTTO WABM/WTTO WVUA 49 LOUISVILLE KY 0.58% WAVE/WAVE-DT2 WAVE/WAVE-DT2 WBKI/WDRB/WMYO WAVE WAVE WBKI/WDRB/WMYO WBKI/WDRB/WMYO WBKI WBKI/WDRB/WMYO WBKI 50 MEMPHIS TN 0.58% WMC WMC WMC WMC WATN/WLMT WBII 51 NEW ORLEANS LA 0.56% WVUE WWL WUPL/WWL WDSU WUPL/WWL WVUE WGNO/WNOL WUPL/WWL WUPL/WWL 57 RICHMOND-PETERSBURG VA 0.48% WUPV/WWBT WTVR WRIC WUPV/WWBT WUPV/WWBT WRIC WRIC WUPV 61 KNOXVILLE TN 0.45% WTNZ EVLT/WVLT EVLT/WVLT WATE EVLT EVLT/WVLT WBXX/WKNX WBXX WBXX/WKNX WBXX 69 HONOLULU HI 0.39% KFVE/KGMB/KHNL KITV KITV KFVE KFVE KHON/KHON-DT2 KFVE KFVE/KHNL KFVE KHON/KHON-DT2 71 TUCSON (SIERRA VISTA) AZ 0.38% KOLD/KOLD-DT2 KOLD/KOLD-DT2 KVOA/KVOA-DT2 KMSB/KTTU KMSB/KTTU KMSB/KTTU KMSB/KTTU KMSB/KTTU KMSB/KTTU KMSB/KTTU 76 TOLEDO OH 0.36% WTOL/WUPW WNWO WTVG-DT2 WTVG/WTVG-DT2 WMNT WMNT WMNT WMNT WMNT 77 COLUMBIA