Charles Dickens and Sovereign Debt John V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Views with Some of the Best Officers on Our Police Force Fully Confirmed This.” Still, One Wonders What Else There Was, Noticed by Neither Source

Readex Report The Flash Press: New York’s Early 19th-Century “Sporting” Underworld as a Unique Source of Slang By Jonathon Green author of Green’s Dictionary of Slang Green’s Dictionary of Slang, launched in print in 2010 and available online since 2016, currently offers some 55,400 entries, in which are nested around 135,000 discrete words and phrases, underpinned by over 655,000 examples of use, known as citations. Thanks to the online environment, it has been possible to offer a regular quarterly update to the dictionary. “Quite simply the best historical dictionary of English slang there is, ever has been…or is ever likely to be.” — Journal of English Language and Linguistics During the summer of 2020, I focused primarily on American Underworld: The Flash Press, a newspaper collection of the American Antiquarian Society and digitized by Readex. Its 45 titles (ranging from a single edition to runs covering multiple years) provided more than two-thirds of additions and changes in last August’s update. In this article, a version of which appeared on my own blog, I write about the nature of the “flash press” and some of the slang terms that have been extracted from it. Here’s this morning’s New York Sewer! Here’s this morning’s New York Stabber! Here’s the New York Family Spy! Here’s the New York Private Listener! Here’s the New York Peeper! Here’s the New York Plunderer! Here’s the New York Keyhole Reporter! Here’s the New York Rowdy Journal — Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) An illustration from “The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit” by Charles Dickens Taking his first steps through 1840s New York City, the young hero of Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit pays a visit to the offices of the New York Rowdy Journal. -

Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU English Faculty Publications English Spring 2000 Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel Cynthia N. Malone College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Cynthia Northcutt Malone. "Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel." Dickens Studies Annual 29 (Spring 2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel Cynthia Northcutt Malone While eighteenth-century British novels are peppered with women ''big with child"-Moll Flanders, Molly Seagrim, Mrs. Pickle-nineteenth century novels typically veil their pregnant characters. Even in nine teenth-century advice books by medical men, circumlocution and euphe mism obscure discussions of pregnancy. This essay explores the changing cultural significance of the female body from the mid-eigh teenth century to the early Victorian period, giving particular attention to the grotesque figure of Mrs. Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit. Through ostentatious circumlocution and through the hilariously grotesque dou bleness of Mrs. Gamp, Dickens both observes and ridicules the Victo rian middle-class decorum enveloping pregnancy in silence. And now one of the new fashions of our very elegant society is to go in perfectly light-coloured dresses-quite tight -witl1out a particle of shawl or scarf .. -

Dickens After Dickens, Pp

CHAPTER 2 Nordic Dickens: Dickensian Resonances in the Work of Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson Kathy Rees, Wolfson College, University of Cambridge On 19 March 1870, the Illustrated London News reported on the last of Charles Dickens’s farewell readings at St. James’s Hall (‘Mr. Chas Dickens’s Farewell Reading’ 301). Three weeks later, Norsk Folkeblad featured this same article, translated into Norwegian (‘Charles Dickens’s Sidste Oplaesning’ 1). At that time, the editor of Norsk Folkeblad was the 38-year-old journalist, novelist, and playwright Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. He recognised the importance of this event and, unlike his English counterpart, he made it front-page news. Bjørnson reproduced both the iconic image of the famous writer at his reading desk and the words of Dickens’s brief curtain speech wherein he bade farewell to his adoring public. Dickens’s novels and journals had long been widely read in Norway, first in German and French translations, later in Danish or Swedish. Sketches by Boz (1836) was popular because of its representation of English customs, especially among the lower classes: one of its tales, ‘Mr Minns and his Cousin’, was included on the English syllabus of Norwegian schools from as early as 1854 (Rem 413). American Notes (1842) was also much discussed on account of the rising numbers of Norwegian emigrants crossing the Atlantic.1 Written Danish and Norwegian were virtually the same language in the How to cite this book chapter: Rees, K. 2020. Nordic Dickens: Dickensian Resonances in the Work of Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. In: Bell, E. (ed.), Dickens After Dickens, pp. 35–55. -

Selected Bibliography on Our Mutual Friend for the 2014 Dickens Universe August 3-9 UC Santa Cruz

Selected Bibliography on Our Mutual Friend for the 2014 Dickens Universe August 3-9 UC Santa Cruz (*starred items are strongly recommended) Reference Works Cotsell, Michael. 1986. The Companion to Our Mutual Friend. Boston: Allen & Unwin; rpt. New York: Routledge, 2009. Brattin, Joel J., and Bert. G. Hornback, eds. 1984. Our Mutual Friend: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland. Heaman, Robert J. 2003. “Our Mutual Friend: An Annotated Bibliography: Supplement I, 1984-2000.” Dickens Studies Annual 33: 425-514. Selected articles and chapters Allen, Michelle Elizabeth. 2008. “A More Expansive Reach: The Geography of the Thames in Our Mutual Friend.” In Cleansing the City: Sanitary Geographies in Victorian London, ch. 2. Athens: Ohio University Press. Alter, Robert. 1996. “Reading Style in Dickens.” Philosophy and Literature 20, no. 1: 130-7. Arac, Jonathan. 1979. “The Novelty of Our Mutual Friend.” In Commissioned Spirits: The Shaping of Social Motion in Dickens, Carlyle, Melville, and Hawthorne, 164-185. New York: Columbia University Press. Baumgarten, Murray. 2000. “The Imperial Child: Bella, Our Mutual Friend, and the Victorian Picturesque.” In Dickens and the Children of Empire, edited by Wendy S. Jacobson, 54-66. New York: Palgrave. Baumgarten, Murray. 2002. “Boffin, Our Mutual Friend, and the Theatre of Fiction.” Dickens Quarterly 19: 17-22. Bodenheimer, Rosemarie. 2002. “Dickens and the Identical Man: Our Mutual Friend Doubled.” Dickens Studies Annual 31: 159-174. Boehm, Katharina. 2013. “Monstrous Births and Saltationism in Our Mutual Friend and Popular Anatomical Museums.” In Charles Dickens and the Sciences of Childhood: Popular Medicine, Child Health and Victorian Culture, ch. 5. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. -

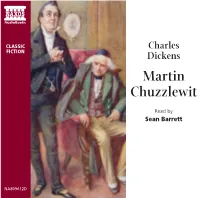

Martin Chuzzlewit

CLASSIC Charles FICTION Dickens Martin Chuzzlewit Read by Sean Barrett NA809612D 1 It was pretty late in the autumn… 5:47 2 ‘Hark!’ said Miss Charity… 6:11 3 An old gentlemen and a young lady… 5:58 4 Mrs Lupin repairing… 4:43 5 A long pause succeeded… 6:21 6 It happened on the fourth evening… 6:16 7 The meditations of Mr Pecksniff that evening… 6:21 8 In their strong feeling on this point… 5:34 9 ‘I more than half believed, just now…’ 5:54 10 You and I will get on excellently well…’ 6:17 11 It was the morning after the Installation Banquet… 4:40 12 ‘You must know then…’ 6:06 13 Martin began to work at the grammar-school… 5:19 14 The rosy hostess scarcely needed… 6:57 15 When Mr Pecksniff and the two young ladies… 5:21 16 M. Todgers’s Commercial Boarding-House… 6:12 17 Todgers’s was in a great bustle that evening… 7:18 18 Time and tide will wait for no man… 4:56 19 ‘It was disinterested too, in you…’ 5:21 20 ‘Ah, cousin!’ he said… 6:28 2 21 The delighted father applauded this sentiment… 5:57 22 Mr Pecksniff’s horse… 5:22 23 John Westlock, who did nothing by halves… 4:51 24 ‘Now, Mr Pecksniff,’ said Martin at last… 6:39 25 They jogged on all day… 5:48 26 His first step, now he had a supply… 7:19 27 For some moments Martin stood gazing… 4:10 28 ‘Now I am going to America…’ 6:49 29 Among these sleeping voyagers were Martin and Mark… 5:01 30 Some trifling excitement prevailed… 5:21 31 They often looked at Martin as he read… 6:05 32 Now, there had been at the dinner-table… 5:05 33 Mr Tapley appeared to be taking his ease… 5:44 34 ‘But stay!’ cried Mr Norris… 4:41 35 Change begets change. -

A Christmas Carol Adapted for the Stage by Geoff Elliott Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott and Geoff Elliott December 2–23, 2021 Edu

A NOISE WITHIN HOLIDAY 2021 AUDIENCE GUIDE Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Adapted for the stage by Geoff Elliott Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott and Geoff Elliott December 2–23, 2021 Edu Pictured: Geoff Elliott and Deborah Strang. Photo by Craig Schwartz. TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Map ......................................3 Synopsis ...........................................4 Quotes from A Christmas Carol .........................5 About the Author Charles Dickens ......................6 Dickensian Timeline: Important Events in Dickens’ Life and Around the World ....8 Dickens’ Times: Victorian London .......................9 Poverty: Life & Death ................................12 Currency & Wealth. .16 About: Scenic Design. .18 About: Costume Design. .19 A Christmas Carol: Overall Design Concept ..............20 Additional Resources . .21 About A Noise Within. 22 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T. and Michael J. Connell Foundation Eileen L. Norris Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Ralph M. Parsons Foundation Coyote Foundation Steinmetz Foundation The Jewish Community Dwight Stuart Youth Fund Foundation 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2021/22 SEASON | Holiday 2021 Audience Guide A Christmas Carol CHARACTER MAP CHRISTMAS PAST CHRISTMAS PRESENT CHRISTMAS YET TO COME EBENEZER SCROOGE The protagonist: a bitter old creditor who does not believe in the spirit of Christmas, nor does he possess any sympathy for the poor. JACOB MARLEY GHOST OF CHRISTMAS GHOST OF CHRISTMAS “Dead to begin with.” PRESENT YET TO COME Ebenezer Scrooge’s former A lively spirit who spreads Scrooge fears this ghost’s business partner, who died seven Christmas cheer. premonitions. years prior. His ghost appears before Scrooge on Christmas Eve to warn of him of the Three Spirits, and urges him to choose a FRED OLD JOE, MRS. -

American Notes for General Circulation by Charles Dickens

AMERICAN NOTES FOR GENERAL CIRCULATION BY CHARLES DICKENS WITH 8 ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARCUS STONE, R.A. LONDON CHAPMAN & HALL, Ltd. 1913 I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO THOSE FRIENDS OF MINE IN AMERICA WHO, GIVING ME A WELCOME I MUST EVER GRATEFULLY AND PROUDLY REMEMBER, LEFT MY JUDGEMENT FREE; AND WHO, LOVING THEIR COUNTRY, CAN BEAR THE TRUTH, WHEN IT IS TOLD GOOD HUMOUREDLY, AND IN A KIND SPIRIT. PREFACE TO THE FIRST CHEAP EDITION OF “AMERICAN NOTES” It is nearly eight years since this book was first published. I present it, unaltered, in the Cheap Edition; and such of my opinions as it expresses, are quite unaltered too. My readers have opportunities of judging for themselves whether the influences and tendencies which I distrust in America, have any existence not in my imagination. They can examine for themselves whether there has been anything in the public career of that country during these past eight years, or whether there is anything in its present position, at home or abroad, which suggests that those influences and tendencies really do exist. As they find the fact, they will judge me. If they discern any evidences of wrong-going in any direction that I have indicated, they will acknowledge that I had reason in what I wrote. If they discern no such thing, they will consider me altogether mistaken. Prejudiced, I never have been otherwise than in favour of the United States. No visitor can ever have set foot on those shores, with a stronger faith in the Republic than I had, when I landed in America. -

Uni International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Beth Penney UCSC September, 2015 the 2015 Dickens Universe

Beth Penney UCSC September, 2015 The 2015 Dickens Universe Climate change was on the minds of many of the attendees at the 2015 Dickens Universe, held August 2-8 at College Eight at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Rather than the cool mornings and warm days Santa Cruz usually provides, there were cloudy afternoons and even a late-week rainstorm. With 250 people in attendance, registration has remained steady over the past few years, thanks in part to the 2011 New Yorker article about the event by this year’s keynote speaker Jill Lepore of Harvard University. This year, there were more faculty and graduate students, with 130 participants from the general public. The number of universities affiliated with UCSC’s Dickens Project continues to grow, with 45 universities in the consortium from across the U.S. and overseas, and others expressing interest. This is the Dickens Universe’s 35th year, and it’s been more than 30 years since the Universe treated Martin Chuzzlewit; American Notes has never been discussed at this forum. This year, an adjunct conference titled “The Long, Wide 19th Century” preceded the week-long Universe, running from July 31 to August 2. On Sunday evening, Dickens Project Director John Jordan segued from one conference to the next by quoting Project co-founder Murray Baumgarten, saying, “Dickens is the railroad station through which everything in the 19th century passes.” He amended that statement by saying that Dickens is also the “port” Penney 2 through which everything passes. The Universe, he said, is a scholarly conference, but “It’s also a place where we come to have fun.” Most conferences, he said, last just two to three days, but this can be thought of as a “residential” conference—and as a summer camp. -

Test Your Knowledge: a Dickens of a Celebration!

A Dickens of a Celebration atKinson f. KathY n honor of the bicentennial of Charles dickens’ birth, we hereby Take the challenge! challenge your literary mettle with a quiz about the great Victorian Iwriter. Will this be your best of times, or worst of times? Good luck! This novel was Dickens and his wife, This famous writer the first of Dickens’ Catherine, had this was a good friend 1 romances. 5 many children; 8 of Dickens and some were named after his dedicated a book to him. (a) David Copperfield favorite authors. (b) Martin Chuzzlewit (a) Mark twain (c) Nicholas Nickleby (a) ten (b) emily Bronte (b) five (c) hans christian andersen (c) nine Many of Dickens’ books were cliffhangers, Where was 2 published in monthly The conditions of the Dickens buried? installments. In 1841, readers in working class are a Britain and the U.S. anxiously 9 common theme in awaited news of the fate of the 6 (a) Portsmouth, england Dickens’ books. Why? pretty protagonist in this novel. (where he was born) (a) he had to work in a (b) Poet’s corner, westminster (a) Little Dorrit warehouse as a boy to abbey, London (b) A Tale of Two Cities help get his family out of (c) isles of scilly (c) The Old Curiosity Shop debtor’s prison. (b) his father worked in a livery and was This amusement This was an early mistreated there. park in Chatham, pseudonym used (c) his mother worked as England, is 3 by Dickens. a maid as a teenager and named10 after Dickens. -

The Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield the Younger Charles Dickens

The Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield the Younger Charles Dickens The Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, Vols. VII & VIII. Selected by Charles William Eliot Copyright © 2001 Bartleby.com, Inc. Bibliographic Record Contents Biographical Note Criticisms and Interpretations I. By Andrew Lang II. By John Forster III. By Adolphus William Ward IV. By Gilbert K. Chesterton V. By W. Teignmouth Shore VI. By George Gissing List of Characters Preface to the First Edition Preface to the “Charles Dickens” Edition I. I Am Born II. I Observe III. I Have a Change IV. I Fall Into Disgrace V. I Am Sent Away from Home VI. Enlarge My Circle of Acquaintance VII. My “First Half” at Salem House VIII. My Holidays. Especially One Happy Afternoon IX. I Have a Memorable Birthday X. I Become Neglected, and Am Provided For XI. I Begin Life on My Own Account, and Don’t Like It XII. Liking Life on My Own Account No Better, I Form a Great Resolution XIII. The Sequel of My Resolution XIV. My Aunt Makes up Her Mind about Me XV. I Make Another Beginning XVI. I Am a New Boy in More Senses Than One XVII. Somebody Turns Up XVIII. A Retrospect XIX. I Look about Me, and Make a Discovery XX. Steerforth’s Home XXI. Little Em’ly XXII. Some Old Scenes, and Some New People XXIII. I Corroborate Mr. Dick and Choose a Profession XXIV. My First Dissipation XXV. Good and Bad Angels XXVI. I Fall into Captivity XXVII. Tommy Traddles XXVIII. Mr. Micawber’s Gauntlet XXIX. -

Dickens' Holiday Classic

Play Guide HOLIDAY 2020 Dickens’ Holiday Classic A VIRTUAL TELLING OF A CHRISTMAS CAROL DECEMBER 19–31 Inside THE NOVELLA Synopsis • 4 “This Ghostly Little Book”: Comments on A Christmas Carol • 5 THE AUTHOR About Charles Dickens • 6 Charles Dickens: A Selected Chronology • 7 A Novel Petition for London’s Poor • 8 CULTURAL CONTEXT Dickens and the Christmas Tradition • 9 Dickens, Scrooge and British Diplomacy • 11 A Scrooge Primer • 13 Victorian Parlor Games • 14 EDUCATION RESOURCES Discussion Questions and Classroom Activities • 16 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 18 Guthrie Theater Play Guide 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 Copyright 2020 ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.447.8243 (toll-free) DRAMATURG Carla Steen guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, Artistic Director GRAPHIC DESIGNER Brian Bressler EDITOR Johanna Buch The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the CONTRIBUTORS Matt DiCintio, Hunter Gullickson, imagination, stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the Jo Holcomb, Matt McGeachy, Siddeeqah Shabazz, illumination of our common humanity. Carla Steen All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this play guide may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publishers. Some materials are written especially for our guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts Board received additional funds to support this activity from the National Endowment for the Arts.