The Nutritional Impact of Grain Fortification and Gluten-Free Diets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients

GUIDELINES ON FOOD FORTIFICATION FORTIFICATION FOOD ON GUIDELINES Interest in micronutrient malnutrition has increased greatly over the last few MICRONUTRIENTS WITH years. One of the main reasons is the realization that micronutrient malnutrition contributes substantially to the global burden of disease. Furthermore, although micronutrient malnutrition is more frequent and severe in the developing world and among disadvantaged populations, it also represents a public health problem in some industrialized countries. Measures to correct micronutrient deficiencies aim at ensuring consumption of a balanced diet that is adequate in every nutrient. Unfortunately, this is far from being achieved everywhere since it requires universal access to adequate food and appropriate dietary habits. Food fortification has the dual advantage of being able to deliver nutrients to large segments of the population without requiring radical changes in food consumption patterns. Drawing on several recent high quality publications and programme experience on the subject, information on food fortification has been critically analysed and then translated into scientifically sound guidelines for application in the field. The main purpose of these guidelines is to assist countries in the design and implementation of appropriate food fortification programmes. They are intended to be a resource for governments and agencies that are currently implementing or considering food fortification, and a source of information for scientists, technologists and the food industry. The guidelines are written from a nutrition and public health perspective, to provide practical guidance on how food fortification should be implemented, monitored and evaluated. They are primarily intended for nutrition-related public health programme managers, but should also be useful to all those working to control micronutrient malnutrition, including the food industry. -

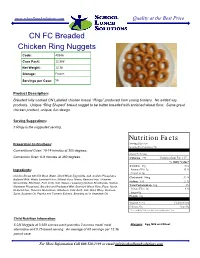

CN FC Breaded Chicken Ring Nuggets Code: 40346 Case Pack: 12.36# Net Weight: 12.36 Storage: Frozen

www.schoollunchsolutions.com Quality at the Best Price CN FC Breaded Chicken Ring Nuggets Code: 40346 Case Pack: 12.36# Net Weight: 12.36 Storage: Frozen Servings per Case: 56 Product Description: Breaded fully cooked CN Labeled chicken breast “Rings” produced from young broilers. No added soy products. Unique “Ring Shaped” breast nugget to be batter breaded with enriched wheat flour. Same great chicken product, unique, fun design. Serving Suggestions: 5 Rings is the suggested serving. Nutrition Facts Preparation Instructions: Serving Size 5 pc Serving Per Container: 56 Conventional Oven: 10-14 minutes at 350 degrees. Amount Per Serving Convection Oven: 6-8 minutes at 350 degrees. Calories 221 Calories from Fat 117 % Daily Value* Total Fat 13g 20% Ingredients: Saturated Fat 3g 15 % Trans Fat 0g Chicken Breast with Rib Meat, Water, Dried Whole Egg Solids, Salt, Sodium Phosphates. Cholesterol 94mg 31 % Battered With: Water, Enriched Flour, (Wheat Flour, Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Sodium 495 21 % Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid), Salt, Spices, Leavening (Sodium Bicarbonate, Sodium Total Carbohydrate 10g 3% Aluminum Phosphate). Breaded and Predusted With: Enriched Wheat Flour (Flour, Niacin, Dietary Fiber 0g 0 % Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid), Salt, Dried Whey, Dextrose, Sugars 0g Spice, Soybean Oil, Paprika and Turmeric Extracts, Breading set in Vegetable Oil. Protein 16g Vitamin A 2% Vitamin C 0% Calcium 2% Iron 6% * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. Child Nutrition Information: 5 CN Nuggets at 0.659 ounces each provides 2 ounces meat/ meat Allergens: Egg, Milk and Wheat alternative and 0.75 bread serving. -

Enriched Flour

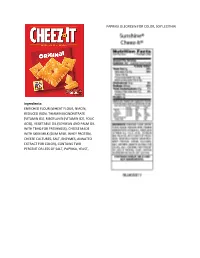

PAPRIKA OLEORESIN FOR COLOR, SOY LECITHIN. Ingredients: ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMIN MONONITRATE [VITAMIN B1], RIBOFLAVIN [VITAMIN B2], FOLIC ACID), VEGETABLE OIL (SOYBEAN AND PALM OIL WITH TBHQ FOR FRESHNESS), CHEESE MADE WITH SKIM MILK (SKIM MILK, WHEY PROTEIN, CHEESE CULTURES, SALT, ENZYMES, ANNATTO EXTRACT FOR COLOR), CONTAINS TWO PERCENT OR LESS OF SALT, PAPRIKA, YEAST, INGREDIENTS CRUST: WHOLE GRAIN OATS, ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, VITAMIN B1 [THIAMIN MONONITRATE], VITAMIN B2 [RIBOFLAVIN], FOLIC ACID), WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, SOYBEAN AND/OR CANOLA OIL, SOLUBLE CORN FIBER, SUGAR, DEXTROSE, FRUCTOSE, CALCIUM CARBONATE, WHEY, WHEAT BRAN, SALT, CELLULOSE, POTASSIUM BICARBONATE, NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR, CINNAMON, MONO- AND DIGLYCERIDES, SOY LECITHIN, WHEAT GLUTEN, NIACINAMIDE, VITAMIN A PALMITATE, CARRAGEENAN, ZINC OXIDE, REDUCED IRON, GUAR GUM, VITAMIN B6 (PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN B1 (THIAMIN HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN B2 (RIBOFLAVIN), FILLING: INVERT SUGAR, CORN SYRUP, APPLE PUREE CONCENTRATE, GLYCERIN, SUGAR, MODIFIED CORN STARCH, SODIUM ALGINATE, MALIC ACID, METHYLCELLULOSE, DICALCIUM PHOSPHATE, CINNAMON, CITRIC ACID, CARAMEL COLOR. CONTAINS WHEAT, MILK AND SOY INGREDIENTS CRUST: WHOLE GRAIN OATS, ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, VITAMIN B1 [THIAMIN MONONITRATE], VITAMIN B2 [RIBOFLAVIN], FOLIC ACID), WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, SOYBEAN AND/OR CANOLA OIL, SOLUBLE CORN FIBER, SUGAR, DEXTROSE, FRUCTOSE, CALCIUM CARBONATE, WHEY, WHEAT BRAN, SALT, CELLULOSE, POTASSIUM -

MOVE! Nutrition Handout N28: Grains

N28 Grains Grains, also known as starches, include foods made from wheat, rice, oats, cornmeal, barley, or other cereal grains. They make up foods such as bread, pasta, rice, cereal, and tortillas. Whole grains, such as whole wheat, are the best choice. Each day, at least half of the grains we eat should be whole grains. Whole grain means it is the “complete” grain. The health benefits of whole grain come from three parts of the grain – the bran (the fibrous coating around the grain), the germ (the nutrient-rich inner part), and the endosperm (the soft white, starchy inside portion). Refined grains have been milled and are usually “white” grains. Milling not only removes most of the fiber, but also removes up to 25% of the grain’s protein and many essential nutrients. Most refined grains are “enriched,” which means certain vitamins (thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, folic acid) and iron are replaced after milling. Fiber is not replaced in enriched grains. www.move.va.gov Nutrition Handouts • N28 Version 5.0 Page 1 of 4 Aim for 3 servings (48 grams) of whole grain foods each day. Food Item 1 Serving = 1 cup dry ready-to-eat or Whole grain cereals ½ cup cooked 1 slice bread or small roll or ½ Whole grain breads bagel, ½ English muffin or ½ hamburger bun Rice (brown) or whole grain ½ cup cooked pasta 1 pancake (5-inch diameter) or 1 small waffle or Other foods made with 1 very small muffin (1 oz.) or whole grain flour 3-4 small crackers or 1 tortilla (6-inch diameter) Tips for Eating Healthy Grains: • When choosing a whole grain food, look for the word “whole” in the ingredient list. -

Breads, Buns, Bagels & Rolls Allergen Information

Food Menu Report: Artisan Bread Item Name Ingredient Statement Allergen Statement Loaves 100% Whole Grain Bread (Whole Grain White Wheat Flour, Water, 10-Grain Cereal [Cracked Whole Wheat, Rye Meal, Corn Meal, Oats, Rye Flour, Soy Grits, Sunflower Seeds, Crushed 100% Whole Grain Hearth Triticale, Barley Flakes, Millet, Flaxseed], Clover Honey, Sea Salt, Yeast, Ascorbic Acid). Contains Soy, Wheat. Asiago Cheese Bread (Unbleached Unbromated Enriched Flour [Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Malted Barley Flour, Water, Asiago Cheese [Pasteurized Asiago Cheese Milk, Cheese Cultures, Enzymes], Sea Salt, Yeast, Malt, Ascorbic Acid). Contains Milk, Wheat. Challah Bread (Unbleached Unbromated Enriched Flour [Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Malted Barley Flour, Water, Organic Eggs, Sugar, Butter [Cream, Challah Salt, Milk], Milk Powder, Sea Salt, Yeast). Contains Egg, Milk, Wheat. Ciabatta Ciabatta Bread (Unbleached Unbromated Enriched Flour [Niacin, Reduced Iron,Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Malted Barley Flour, Water, Sea Salt, Yeast, Ascorbic Acid. Contains Wheat. Classic 10 Grain Bread (Unbleached Unbromated Enriched Flour [Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Malted Barley Flour, Water, 10-Grain Cereal [Cracked Whole Wheat, Rye Meal, Corn Meal, Oats, Rice Flour, Soy Grits, Sunflower Seeds, Crushed Triticale, Barley Flakes, Millet, Flaxseed], Stone Ground Whole Wheat Flour, Clover Honey, Sea Salt, Classic 10 Grain Yeast, Ascorbic Acid). Contains Soy, Wheat. French Boule/Baguette (Unbleached Unbromated Enriched Flour [Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Malted Barley Flour, Water, Sea Salt, Yeast, Malt, French Baguette Ascorbic Acid). Contains Wheat. French Boule/Baguette (Unbleached Unbromated Enriched Flour [Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Malted Barley Flour, Water, Sea Salt, Yeast, Malt, French Boule Ascorbic Acid). -

21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–10 Edition) § 137.165

§ 137.165 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–10 Edition) § 137.165 Enriched flour. to the food for enrichment purposes Enriched flour conforms to the defi- may be supplied by any safe and suit- able substance. Niacin equivalents as nition and standard of identity, and is derived from tryptophan content shall subject to the requirements for label not be used in determining total niacin statement of ingredients, prescribed content. for flour by § 137.105, except that: (a) It contains in each pound 2.9 mil- [42 FR 14402, Mar. 15, 1977, as amended at 43 ligrams of thiamin, 1.8 milligrams of FR 38578, Aug. 29, 1978; 46 FR 43414, Aug. 28, riboflavin, 24 milligrams of niacin, 0.7 1981; 58 FR 2877, Jan. 6, 1993; 61 FR 8796, Mar. milligrams of folic acid, and 20 milli- 5, 1996] grams of iron. § 137.170 Instantized flours. (b) It may contain added calcium in such quantity that the total calcium (a) Instantized flours, instant blend- content is 960 milligrams per pound. ing flours, and quick-mixing flours, are Enriched flour may be acidified with the foods each of which conforms to monocalcium phosphate within the the definition and standard of identity limits prescribed by § 137.175 for and is subject to the requirement for phosphated flour, but, if insufficient label statement of ingredients pre- additional calcium is present to meet scribed for the corresponding kind of the 960 milligram level, no claim may flour by §§ 137.105, 137.155, 137.160, be made on the label for calcium as a 137.165, 137.175, 137.180, and 137.185, ex- nutrient; cept that each such flour has been (c) The requirement of paragraphs (a) made by one of the optional procedures and (b) of this section will be deemed set forth in paragraph (b) of this sec- to have been met if reasonable over- tion, and is thereby made readily pour- ages of the vitamins and minerals, able. -

Choose Whole Grains

Choose Whole Grains Did you know that Canada’s Food Guide says Are you eating whole grains? whole grain foods are a healthier choice than refined grains? Below are some tips to help you figure out if a food is really a whole grain food. Whole grains increase your fibre intake and have a lot of nutrients working together to promote Look at the ingredient list health. Choose grain foods that have whole grains Whole grains give your body carbohydrates, fibre, listed as the first grain ingredient. and protein. They also provide B vitamins, iron, In the ingredient list, the grains below should zinc, magnesium, and plant compounds called have the words whole or whole grain in front phytonutrients. of their name. whole grain whole whole rye What is a whole grain? wheat whole grain (or whole wheat berries hulled) barley are made of the entire grain kernel. Whole grains whole spelt The kernel has three parts: the outer bran layer, the endosperm, and the germ. Each part has important The grains below don’t need the words nutrients. whole or whole grain in front of their name. This is because in foods, they are used only as whole grains. amaranth popcorn buckwheat quinoa bulgur sorghum cornmeal sprouted wheat cracked wheat teff kamut triticale millet wild or brown rice oats and oatmeal When a food package says the food is whole Refined grains have all or part of the bran and grain, read the ingredient list to find out for germ removed. They don’t have important sure. The food might have some whole grains nutrients like fibre, vitamins, and minerals. -

Enriched Bromated Flour. Ride Hydro- Chloride

§ 137.155 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–11 Edition) the residue on the No. 70 sieve and con- be made on the label for calcium as a vert to percentage. nutrient; (c) The requirement of paragraphs (a) [42 FR 14402, Mar. 15, 1977, as amended at 47 and (b) of this section will be deemed FR 11827, Mar. 19, 1982; 47 FR 24693, June 8, 1982; 47 FR 43363, Oct. 1, 1982; 49 FR 10097, to have been met if reasonable over- Mar. 19, 1984; 54 FR 24894, June 12, 1989; 58 FR ages of the vitamins and minerals, 2877, Jan. 6, 1993] within the limits of good manufac- turing practice, are present to insure § 137.155 Bromated flour. that the required levels of the vitamins Bromated flour conforms to the defi- and minerals are maintained through- nition and standard of identity, and is out the expected shelf life of the food subject to the requirements for label under customary conditions of dis- statement of ingredients, prescribed tribution and storage. The quantitative for flour by § 137.105, except that potas- content of the following vitamins shall sium bromate is added in a quantity be calculated in terms of the following not exceeding 50 parts to each million chemically identifiable reference parts of the finished bromated flour, forms: and is added only to flours whose bak- Reference form ing qualities are improved by such ad- Vitamin Molec- dition. Name Empirical formula ular weight [57 FR 2877, Jan. 6, 1993] Thiamine ... Thiamine chlo- C12H17ClN4OS·HCl 337 .28 § 137.160 Enriched bromated flour. -

Whole Wheat Flour, Enriched Wheat Flour 17.6G 16G

Formulation Statement for Documenting Grains in School Meals Required Beginning SY 2013-2014 (Crediting Standards Based on Grams of Creditable Grains) School Food Authorities (SFAs) should include a copy of the label from the purchased product package in addition to the following information on letterhead signed by an official company representative. Grain products may be credited based on previous standards through SY 2012-2013. The new crediting standards for grains (as outlined in Policy Memorandum SP 30-2012) must be used beginning SY 2013-2014. SFAs have the option to choose the crediting method that best fits the specific needs of the menu planner. Product Name: Cheez-It® Crackers made with 9g Whole Grain Atomic Cheddar Code No.: 24100 10238 Manufacturer: Kellogg Company Serving Size: 1 pouch (0.75 oz) (21 g) (raw dough weight may be used to calculate creditable grain amount) I. Does the product meet the Whole Grain-Rich Criteria: Yes X No (Refer to SP 30-2012 Grain Requirements for the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program) II. Does the product contain noncreditable grains: Yes X No How many grams: <3.99 (Products with more than 0.24 oz equivalent or 3.99 grams for Groups A-G or 6.99 grams for Group H of noncreditable grains may not credit towards the grain requirements for school meals). III. Use Policy Memorandum SP 30-2012 Grain Requirements for the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: Exhibit A to determine if the product fits into Groups A-G (baked goods), Group H (cereal grains), or Group I (ready-to-eat breakfast cereals). -

The State of Science Regarding Consumption of Refined and Enriched Grains

The State of Science Regarding Consumption of Refined and Enriched Grains Judi Adams1 The AACC International (AACCI) Scientific Advisory Panel and AACCI leaders have identified “Unifying the Grain Health Benefits Message” as one of five scientific opportunity areas. To this end, a two-day thought-leader meeting was held in January 2013 (17). One of the proposed action steps from this meeting was to develop a review of the benefits of grains. This is the second in a series of papers that will be published in Cereal Foods World to provide unified grain health messages as part of this scientific initiative. Sometimes called “the quiet miracle,” they are harmful. An estimated 4–6% of U.S. children under age enrichment of refined flour was initi- 18 and 4% of adults have food allergies (23). Although wheat is ated voluntarily in 1941 during World one of the eight most common food allergens in the United War II by U.S. bakers and millers (and States, less than 0.5% of Americans are allergic to wheat. None- was later mandated by the War Food theless, as one of the “big eight,” it is covered under the food Administration). The three main B vita- allergy labeling law of 2004, and food manufacturers are required mins (riboflavin, niacin, and thiamin) to clearly list wheat on food labels (11). and iron were added back into refined It is important to distinguish food allergies from other non– flour in amounts equal to or higher than immune-mediated adverse reactions to foods, particularly since those found in whole grain flour. -

Ingredient Label Information 1

Ingredient Label Information * Spices and Herbs may be used in some items. 1 Contact your school cafeteria personal for more information. Apple Frudel Water, Whole Wheat Flour, Enriched Flour,(Wheat Flour, Malted Barley Flour, Niacin, Iron, (Pillsbury) Thiamin, Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid), Apple Strudel Filling (Water, Sugar, Corn Syrup, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Modified Corn Starch, Apple Pulp, Fractioned Palm Kernel Oil, Malic Acid, Molasses, Sodium Citrate, Salt, Sodium Benzoate (Preservative), Gellan Gum, Spice, Xanlthan Gum, Locust Bean Gum, Carrageenan, Natural Flavor), Sugar,, Palm Oil, Canola Oil, Yeast, Soybean Oil, Contains 2% Or Less Of: Nonfat Milk, Salt, Natural Flavor,, TBHQ (Preservative). Contains Wheat and Milk. Applesauce (USDA) Apples, Sorbic Acid, Water Bacon Bits - Turkey White Turkey, Mechanically Separated Turkey, Turkey Fat, Salt, Sugar, Water, contains 2% Or (Jennio) Less Bacon Type Flavor (Maltodextrin, Gum Acacia, Natural And Artificial Flavoring, Hydrolyzed Corn Protein, Yeast Extact, Modified Corn Starch, Exnthan Gum, Succinic Acid), Natural Smoke Flavoring, Sodium Erythorbate, Natural Flavoring, Smoke Bacon Flavor (Maltodextrin, Autolyzed Yeast Extract, Natural Flavor (Contains Natural Smoke Flavor), Sugar, Salt), Sodium Nitrite, Vegetable Oil. Baked Beans Prepared White Beans, Water, Sugar, Brown Sugar, Tomato Paste, Salt, Bacon, Mustard (Water, (Bushes) Vinegar, Mustard Seed, Salt, Turmeric, Spiced), Onion Powder, Spices, Extractive Of Paprika, Garlic Powder, And Natural Flavor. Contains: Pork Baked Chicken Chicken Parts, Water, Salt, Sodium Phosphates And Citric Acid. (Gold Kist Farms) Barbecue Sauce Tomato Paste, Distilled Vinegar, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Salt, Spices, Natural Smoke PPC (Heniz) Flavoring, Paprika, Soybean Oil, Dehydrated Soy Sauce (Soybeans, Wheat, Salt), Garlic Powder, Guar Gum, Sodium Benzoate, Onion Powder, Dextrose, Turmeric, Natural flavor. -

Crediting Enriched Grains in the NSLP and SBP

Crediting Enriched Grains in the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program School Year 2021-22 This guidance applies to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) meal patterns for grades K-12 and preschoolers (ages 1-4) in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), School Breakfast Program (SBP), Seamless Summer Option (SSO) of the NSLP, and Afterschool Snack Program (ASP) of the NSLP. The SSO follows the NSLP and SBP meal patterns. The requirements for the preschool meal patterns are the same as the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), and are defined by the USDA’s final rule, Child and Adult Care Food Program: Meal Pattern Revisions Related to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. For a comparison of each program’s meal pattern requirements for the grains component, refer to the Connecticut State Department of Education’s (CSDE) resource, Comparison of Meal Pattern Requirements for the Grains Component in the School Nutrition Programs. For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods for grades K-12, visit the CSDE’s webpages, Meal Patterns for Grades K-12 in School Nutrition Programs, Crediting Foods for Grades K-12 in the ASP, and Crediting Foods in School Nutrition Programs. For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods for preschoolers, visit the Connecticut State Department of Education’s (CSDE) Meal Patterns for Preschoolers in School Nutrition Programs webpage. Enriched grains are refined grains (such as wheat, rice, and corn) and grain products (such as cereal, pasta, and bread) that have certain vitamins and minerals added to replace some of the nutrients lost during processing.