Amplitude Modulation (AM)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

ETR 132 TECHNICAL August 1994 REPORT

ETSI ETR 132 TECHNICAL August 1994 REPORT Source: EBU/ETSI JTC Reference: DTR/JTC-00011 ICS: 33.060 Key words: Broadcasting, FM, radio, transmitter, VHF European Broadcasting Union Union Européenne de Radio-Télévision EBU UER Radio broadcasting systems; Code of practice for site engineering Very High Frequency (VHF), frequency modulated, sound broadcasting transmitters ETSI European Telecommunications Standards Institute ETSI Secretariat Postal address: F-06921 Sophia Antipolis CEDEX - FRANCE Office address: 650 Route des Lucioles - Sophia Antipolis - Valbonne - FRANCE X.400: c=fr, a=atlas, p=etsi, s=secretariat - Internet: [email protected] Tel.: +33 92 94 42 00 - Fax: +33 93 65 47 16 Copyright Notification: No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. The copyright and the foregoing restriction extend to reproduction in all media. © European Telecommunications Standards Institute 1994. All rights reserved. New presentation - see History box © European Broadcasting Union 1994. All rights reserved. Page 2 ETR 132: August 1994 Whilst every care has been taken in the preparation and publication of this document, errors in content, typographical or otherwise, may occur. If you have comments concerning its accuracy, please write to "ETSI Editing and Committee Support Dept." at the address shown on the title page. Page 3 ETR 132: August 1994 Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................7 1 Scope -

3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems

63 3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems 3.1 Representation of Bandpass Signals and Systems Narrowband communication signals are often transmitted using some type of carrier modulation. The resulting transmit signal s(t) has passband character, i.e., the bandwidth B of its spectrum S(f) = s(t) is much smaller F{ } than the carrier frequency fc. S(f) B f f f − c c We are interested in a representation for s(t) that is independent of the carrier frequency fc. This will lead us to the so–called equiv- alent (complex) baseband representation of signals and systems. Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 64 3.1.1 Equivalent Complex Baseband Representation of Band- pass Signals Given: Real–valued bandpass signal s(t) with spectrum S(f) = s(t) F{ } Analytic Signal s+(t) In our quest to find the equivalent baseband representation of s(t), we first suppress all negative frequencies in S(f), since S(f) = S( f) is valid. − The spectrum S+(f) of the resulting so–called analytic signal s+(t) is defined as S (f) = s (t) =2 u(f)S(f), + F{ + } where u(f) is the unit step function 0, f < 0 u(f) = 1/2, f =0 . 1, f > 0 u(f) 1 1/2 f Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 65 The analytic signal can be expressed as 1 s+(t) = − S+(f) F 1{ } = − 2 u(f)S(f) F 1{ } 1 = − 2 u(f) − S(f) F { } ∗ F { } 1 The inverse Fourier transform of − 2 u(f) is given by F { } 1 j − 2 u(f) = δ(t) + . -

Microwave Frequency Demodulation Using Two Coupled Optical Resonators with Modulated Refractive Index

PHYSICAL REVIEW APPLIED 15, 034056 (2021) Microwave Frequency Demodulation Using two Coupled Optical Resonators with Modulated Refractive Index Adam Mock * School of Engineering and Technology, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan 48859, USA (Received 16 October 2020; revised 1 February 2021; accepted 10 February 2021; published 18 March 2021) Traditional electronic frequency demodulation of a microwave frequency voltage is challenging because it requires complicated phase-locked loops, narrowband filters with fixed passbands, or large footprint local oscillators and mixers. Herein, a different frequency demodulation concept is proposed based on refractive index modulation of two coupled microcavities excited by an optical wave. A frequency- modulated microwave frequency voltage is applied to two photonic crystal microcavities in a spatially odd configuration. The spatially odd perturbation causes coupling between the even and odd supermodes of the coupled-cavity system. It is shown theoretically and verified by finite-difference time-domain sim- ulations how careful choice of the modulation amplitude and frequency can switch the optical output from on to off. As the modulating frequency is detuned from its off value, the optical output switches from off to on. Ultimately, the optical output amplitude is proportional to the frequency deviation of the applied voltage making this device a frequency-modulated-voltage to amplitude-modulated-optical- wave converter. The optical output can be immediately detected and converted to a voltage that would result in a frequency-demodulated voltage signal. Or the optical output can be fed into a larger radio- over-fiber optical network. In this case the device presents a compact, low power, and tunable route for multiplexing frequency-modulated voltages with amplitude-modulated optical communication systems. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

Oscillating Currents

Oscillating Currents • Ch.30: Induced E Fields: Faraday’s Law • Ch.30: RL Circuits • Ch.31: Oscillations and AC Circuits Review: Inductance • If the current through a coil of wire changes, there is an induced emf proportional to the rate of change of the current. •Define the proportionality constant to be the inductance L : di εεε === −−−L dt • SI unit of inductance is the henry (H). LC Circuit Oscillations Suppose we try to discharge a capacitor, using an inductor instead of a resistor: At time t=0 the capacitor has maximum charge and the current is zero. Later, current is increasing and capacitor’s charge is decreasing Oscillations (cont’d) What happens when q=0? Does I=0 also? No, because inductor does not allow sudden changes. In fact, q = 0 means i = maximum! So now, charge starts to build up on C again, but in the opposite direction! Textbook Figure 31-1 Energy is moving back and forth between C,L 1 2 1 2 UL === UB === 2 Li UC === UE === 2 q / C Textbook Figure 31-1 Mechanical Analogy • Looks like SHM (Ch. 15) Mass on spring. • Variable q is like x, distortion of spring. • Then i=dq/dt , like v=dx/dt , velocity of mass. By analogy with SHM, we can guess that q === Q cos(ωωω t) dq i === === −−−ωωωQ sin(ωωω t) dt Look at Guessed Solution dq q === Q cos(ωωω t) i === === −−−ωωωQ sin(ωωω t) dt q i Mathematical description of oscillations Note essential terminology: amplitude, phase, frequency, period, angular frequency. You MUST know what these words mean! If necessary review Chapters 10, 15. -

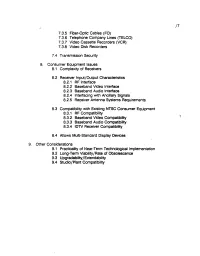

7.3.7 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) 7.3.8 Video Disk Recorders

/7 7.3.5 Fiber-Optic Cables (FO) 7.3.6 Telephone Company Unes (TELCO) 7.3.7 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) 7.3.8 Video Disk Recorders 7.4 Transmission Security 8. Consumer Equipment Issues 8.1 Complexity of Receivers 8.2 Receiver Input/Output Characteristics 8.2.1 RF Interface 8.2.2 Baseband Video Interface 8.2.3 Baseband Audio Interface 8.2.4 Interfacing with Ancillary Signals 8.2.5 Receiver Antenna Systems Requirements 8.3 Compatibility with Existing NTSC Consumer Equipment 8.3.1 RF Compatibility 8.3.2 Baseband Video Compatibility 8.3.3 Baseband Audio Compatibility 8.3.4 IDTV Receiver Compatibility 8.4 Allows Multi-Standard Display Devices 9. Other Considerations 9.1 Practicality of Near-Term Technological Implementation 9.2 Long-Term Viability/Rate of Obsolescence 9.3 Upgradability/Extendability 9.4 Studio/Plant Compatibility Section B: EXPLANATORY NOTES OF ATTRIBUTES/SYSTEMS MATRIX Items on the Attributes/System Matrix for which no explanatory note is provided were deemed to be self-explanatory. I. General Description (Proponent) section I shall be used by a system proponent to define the features of the system being proposed. The features shall be defined and organized under the headings ot the following subsections 1 through 4. section I. General Description (Proponent) shall consist of a description of the proponent system in narrative form, which covers all of the features and characteris tics of the system which the proponent wishe. to be included in the public record, and which will be used by various groups to analyze and understand the system proposed, and to compare with other propo.ed systems. -

Maintenance of Remote Communication Facility (Rcf)

ORDER rlll,, J MAINTENANCE OF REMOTE commucf~TIoN FACILITY (RCF) EQUIPMENTS OCTOBER 16, 1989 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION AbMINISTRATION Distribution: Selected Airway Facilities Field Initiated By: ASM- 156 and Regional Offices, ZAF-600 10/16/89 6580.5 FOREWORD 1. PURPOSE. direction authorized by the Systems Maintenance Service. This handbook provides guidance and prescribes techni- Referenceslocated in the chapters of this handbook entitled cal standardsand tolerances,and proceduresapplicable to the Standardsand Tolerances,Periodic Maintenance, and Main- maintenance and inspection of remote communication tenance Procedures shall indicate to the user whether this facility (RCF) equipment. It also provides information on handbook and/or the equipment instruction books shall be special methodsand techniquesthat will enablemaintenance consulted for a particular standard,key inspection element or personnel to achieve optimum performancefrom the equip- performance parameter, performance check, maintenance ment. This information augmentsinformation available in in- task, or maintenanceprocedure. struction books and other handbooks, and complements b. Order 6032.1A, Modifications to Ground Facilities, Order 6000.15A, General Maintenance Handbook for Air- Systems,and Equipment in the National Airspace System, way Facilities. contains comprehensivepolicy and direction concerning the development, authorization, implementation, and recording 2. DISTRIBUTION. of modifications to facilities, systems,andequipment in com- This directive is distributed to selectedoffices and services missioned status. It supersedesall instructions published in within Washington headquarters,the FAA Technical Center, earlier editions of maintenance technical handbooksand re- the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center, regional Airway lated directives . Facilities divisions, and Airway Facilities field offices having the following facilities/equipment: AFSS, ARTCC, ATCT, 6. FORMS LISTING. EARTS, FSS, MAPS, RAPCO, TRACO, IFST, RCAG, RCO, RTR, and SSO. -

Reception Performance Improvement of AM/FM Tuner by Digital Signal Processing Technology

Reception performance improvement of AM/FM tuner by digital signal processing technology Akira Hatakeyama Osamu Keishima Kiyotaka Nakagawa Yoshiaki Inoue Takehiro Sakai Hirokazu Matsunaga Abstract With developments in digital technology, CDs, MDs, DVDs, HDDs and digital media have become the mainstream of car AV products. In terms of broadcasting media, various types of digital broadcasting have begun in countries all over the world. Thus, there is a demand for smaller and thinner products, in order to enhance radio performance and to achieve consolidation with the above-mentioned digital media in limited space. Due to these circumstances, we are attaining such performance enhancement through digital signal processing for AM/FM IF and beyond, and both tuner miniaturization and lighter products have been realized. The digital signal processing tuner which we will introduce was developed with Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. for the 2005 line model. In this paper, we explain regarding the function outline, characteristics, and main tech- nology involved. 22 Reception performance improvement of AM/FM tuner by digital signal processing technology Introduction1. Introduction from IF signals, interference and noise prevention perfor- 1 mance have surpassed those of analog systems. In recent years, CDs, MDs, DVDs, and digital media have become the mainstream in the car AV market. 2.2 Goals of digitalization In terms of broadcast media, with terrestrial digital The following items were the goals in the develop- TV and audio broadcasting, and satellite broadcasting ment of this digital processing platform for radio: having begun in Japan, while overseas DAB (digital audio ①Improvements in performance (differentiation with broadcasting) is used mainly in Europe and SDARS (satel- other companies through software algorithms) lite digital audio radio service) and IBOC (in band on ・Reduction in noise (improvements in AM/FM noise channel) are used in the United States, digital broadcast- reduction performance, and FM multi-pass perfor- ing is expected to increase in the future. -

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation Prof Eduardo R Miranda Varèse-Gastprofessor [email protected] Electronic Music Studio TU Berlin Institute of Communications Research http://www.kgw.tu-berlin.de/ Topics: Additive Synthesis Amplitude Modulation (and Ring Modulation) Frequency Modulation Additive Synthesis • The technique assumes that any periodic waveform can be modelled as a sum sinusoids at various amplitude envelopes and time-varying frequencies. • Works by summing up individually generated sinusoids in order to form a specific sound. Additive Synthesis eg21 Additive Synthesis eg24 • A very powerful and flexible technique. • But it is difficult to control manually and is computationally expensive. • Musical timbres: composed of dozens of time-varying partials. • It requires dozens of oscillators, noise generators and envelopes to obtain convincing simulations of acoustic sounds. • The specification and control of the parameter values for these components are difficult and time consuming. • Alternative approach: tools to obtain the synthesis parameters automatically from the analysis of the spectrum of sampled sounds. Amplitude Modulation • Modulation occurs when some aspect of an audio signal (carrier) varies according to the behaviour of another signal (modulator). • AM = when a modulator drives the amplitude of a carrier. • Simple AM: uses only 2 sinewave oscillators. eg23 • Complex AM: may involve more than 2 signals; or signals other than sinewaves may be employed as carriers and/or modulators. • Two types of AM: a) Classic AM b) Ring Modulation Classic AM • The output from the modulator is added to an offset amplitude value. • If there is no modulation, then the amplitude of the carrier will be equal to the offset. -

En 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12)

Draft ETSI EN 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12) HARMONISED EUROPEAN STANDARD Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) on-board vessels communications systems and equipment; Harmonised Standard covering the essential requirements of article 3.2 of the Directive 2014/53/EU 2 Draft ETSI EN 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12) Reference REN/ERM-TG26-136 Keywords Harmonised Standard, maritime, radio, UHF ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice The present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org/standards-search The present document may be made available in electronic versions and/or in print. The content of any electronic and/or print versions of the present document shall not be modified without the prior written authorization of ETSI. In case of any existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions and/or in print, the only prevailing document is the print of the Portable Document Format (PDF) version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: https://portal.etsi.org/People/CommiteeSupportStaff.aspx Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm except as authorized by written permission of ETSI. -

Chapter 7 Amplitude Modulation

page 7.1 CHAPTER 7 AMPLITUDE MODULATION Transmit information-b earing message or baseband signal voice-music through a Communications Channel Baseband = band of frequencies representing the original signal for music 20 Hz - 20,000 Hz, for voice 300 - 3,400 Hz write the baseband message signal mt $ M f Communications Channel Typical radio frequencies 10 KHz ! 300 GHz write ct= A cos2f ct c ct = Radio Frequency Carrier Wave A = Carrier Amplitude c fc = Carrier Frequency Amplitude Mo dulation AM ! Amplitude of carrier wavevaries a mean value in step with the baseband signal mt st= A [1 + k mt] cos 2f t c a c Mean value A . c 31 page 7.2 Recall a general signal st= at cos[2f t + t] c For AM at = A [1 + k mt] c a t = 0 or constant k = Amplitude Sensitivity a Note 1 jk mtj < 1or [1 + k mt] > 0 a a 2 f w = bandwidth of mt c 32 page 7.3 AM Signal In Time and Frequency Domain st = A [1 + k mt] cos 2f t c a c j 2f t j 2f t c c e + e st = A [1 + k mt] c a 2 A A c c j 2f t j 2f t c c e + e st = 2 2 A k c a j 2f t c + mte 2 A k c a j 2f t c + mte 2 To nd S f use: mt $ M f j 2f t c e $ f f c j 2f t c e $ f + f c expj 2f tmt $ M f f c c expj 2f tmt $ M f + f c c A c S f = [f f +f +f ] c c 2 A k c a + [M f fc+Mf +f ] c 2 33 page 7.4 st = A [1 + k mt] cos 2f t c a c A c = [1 + k mt][expj 2f t+ expj 2f t] a c c 2 If k mt > 1, then a ! Overmo dulation ! Envelop e Distortion see Text p.