Speaking Truth Through Power Conceptualizing Internal Whistleblowing Hotlines with Foucault’S Dispositive Du Plessis, Erik Mygind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Speaking Truth to Power: Citizens and the Law”

JUSTICE MC CHAGLA MEMORIAL LECTURE 2021 “Speaking Truth to Power: Citizens and the Law” Dr Justice Dhananjaya Y Chandrachud Judge, Supreme Court of India It is an honour for me to have been invited to speak at this lecture organised in the memory of one of the greatest legal minds India has ever witnessed – Justice Mohammadali Carim Chagla. In no uncertain terms, Justice Chagla has profoundly influenced and impacted the development of law and protection of civil liberties in India. He donned many diverse roles during his lifetime, among them being that of a lawyer, judge, jurist, diplomat, and Cabinet Minister. After studying at the University of Oxford, he joined the Bombay Bar in 1922 and practised as a lawyer for 19 years in the High Court of Bombay before he was appointed as a Judge, and subsequently the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court. Though he received an offer for appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court of India, he let the offer pass since he believed that he would be able to initiate more changes as the Chief Justice of a High Court than he ever would be able to as a puisne judge of the Supreme Court. After his retirement, he served as an ad-hoc judge in the International Court of Justice, India’s ambassador to the United States and United Kingdom, before taking oath as a Cabinet Minister, taking on the portfolio of Education and then External Affairs. Only a few others could possibly come close to the diversity of roles Chief Justice Chagla took on and yet, unsurprisingly, he managed to excel in each of them. -

Intelligence Ethics 2007.Pdf

Intelligence Ethics: The Definitive Work of 2007* Published by the Center for the Study of Intelligence and Wisdom Edited by Michael Andregg About the Eyes A spy asked, “Why the eyes?” They are the eyes of my daughter, who deserves a decent world to grow up in. They are the eyes of your mother, who deserves a decent peace to grow old in. They are the eyes of children blown to shreds by PGMs sent to the wrong address by faulty intelligence. And they are the eyes of children blown to shreds by suicide bombers inspired by faulty intelligence. They are the eyes of orphans and they are the eyes of God, wondering who fears ethical thought and why. Grandmother says it is time to grow up. The nation is in danger and the children are in peril. So sometimes you can set long books of rules aside and use the ancient Grandma Test. If she were watching, and knew everything you do, would she really approve? Copyright © 2007 by Michael Murphy Andregg All rights reserved. Published in the United States by the Center for the Study of Intelligence and Wisdom, an imprint of Ground Zero Minnesota in St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Andregg, Michael M. ISBN 0-9773-8181-1 1. Ethics. 2. Intelligence Studies. 3. Human Survival. Printed in the United States of America First Edition A generic Disclaimer : Many of our authors have had diverse and interesting government backgrounds and some are still on active duty. Others are professors of intelligence studies with active security clearances. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Achenbaum, W.A. 1983. The making of an applied historian: Stage two. The Public Historian 5(2): 21–46. American Friends Service Committee. 1955. Speak truth to power: A Quaker search for an alternative to violence . Philadelphia: American Friends Service Committee. American Historical Association. 2011. Statement on standards of professional con- duct . Washington, DC: American Historical Association. Anderson, O. 1967. The political uses of history in mid nineteenth-century England. Past & Present 36: 87–105. Ankersmit, F.R. 1989. Historiography and postmodernism. History and Theory 28(2): 137–153. Ashby, R., and C. Edwards. 2010. Challenges facing the disciplinary tradition: Refl ections on the history curriculum in England. In Contemporary public debates over history education , ed. I. Nakou and I. Barca, 27–46. Greenwich: Information Age. Ashford, D.E. (ed.). 1992. History and context in comparative public policy . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Ashton, P., and H. Kean. 2009. People and their pasts: Public history today . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Balogh, T. 1959. The apotheosis of the dilettante: The establishment of Mandarins. In The establishment: A symposium , ed. H. Thomas. London: Anthony Blond. Banner, J.M. 2012. Being a historian: An introduction to the professional world of history . Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press. Barker, H., M. McLean, and M. Roseman. 2000. Re-thinking the history curricu- lum: Enhancing students’ communication and group-work skills. In The prac- © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 125 A.R. Green, History, Policy and Public Purpose, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-52086-9 126 BIBLIOGRAPHY tice of university history teaching , ed. -

Edward Snowden, Hero Or Traitor? an Analysis of News Media Framing a Senior Project

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DigitalCommons@CalPoly Edward Snowden, Hero or Traitor? An Analysis of News Media Framing A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the Communication Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts by Cole N. Caster June, 2016 Dr. Richard Besel Senior Project Advisor Signature Date Dr. Bernard K. Duffy Department Chair Signature Date Caster 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………………………………………...2 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Literature Review ……………………………………………………………………………………….............5 Method ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 Results ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...13 Discussion / Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………….16 Works Cited ………………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Appendix…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...20 Video Link………………………………………………………………………………………………………….27 Caster 3 Introduction Throughout history, the methods and motivations behind communication have continuously evolved. There has been a constant move towards developing ways to communicate with one another over longer distances, using less effort, fewer resourses, and increasing the amount of data we can send at once. What has come with this trend is the explosion of communication opportunities. We are now able to communicate with one another with greater ease than ever before, and because of this, we communicate -

News Online 24 June 2015 (14/15)

News Online 24 June 2015 (14/15) Home page: http://www.statewatch.org/ e-mail: [email protected] News 1. EU: Council of the European Union: LIMITE docs: inc "Countering Hybrid Threats" 2. EU: Net neutrality in critical danger in Europe. The time to act is NOW! 3. EU: EP study: Surveillance and censorship: The impact of technologies on human rights 4. EU: EP study: Towards more effective global humanitarian action: How the EU can contribute 5. EU: European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS): Trade agreements and data 6. EU: DATA PROTECTION REGULATION: Article 29 Data Protection WP 7. Essential viewing: Building on communities of dissent (Institute of Race Relations) 8. UK: Will the government’s counter-extremism programme criminalise dissent? (IRR) 9. EU: Promoting Intra EU labour mobility of international protection beneficiaries 10. EU Transparency and decision-making:NON-PAPER 11. EU Court: Estonia website liable for readers’ offensive online comments 12. Online book Chapter: Speaking Truth to Power? by Ann Singleton 13. Intelligence, security and privacy: A Note by the Director (Ditchley Park) 14. EU: Council of the European Union: Data Protection Regulation 15. EU: Council of the European Union: Connected Continent 16. UK: The Police Are Scanning the Faces of Every Single Person at Download 2015 17. EU: Justice and Home Affairs Council, 15-16 June, Luxembourg 18. UK: MINERS STRIKE 1984-1985: ORGREAVE 19. UK: UNDERCOVER POLICE: Drax & IPPC 20. UK: SURVEILLANCE POWERS: Report Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation 21. EU: European Commission: Internal Security Fund 22. BELGIUM: The Constitutional Court repeals the transposition of the data retention directive 23. -

Eyewitness to History in Devolution of Democracy and Constitutional Rights Following 9/11 Thomas Drake Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2017 Eyewitness to History in Devolution of Democracy and Constitutional Rights Following 9/11 Thomas Drake Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Thomas Drake has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. George Larkin, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Ron Hirschbein, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Tanya Settles, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2017 Abstract Eyewitness to History in Devolution of Democracy and Constitutional Rights Following 9/11 by Thomas A. Drake Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Public Policy and Administration Walden University May 2017 Abstract Many researchers and political experts have commented on the disenfranchisement of the citizenry caused by irresponsible use of power by the government that potentially violates the 4th Amendment rights of millions of people through secret mass surveillance programs. Disclosures of this abuse of power are presumably protected by the 1st Amendment, though when constitutional protections are not followed by the government, the result can be prosecution and imprisonment of whistleblowers. -

Remnants of Dissent

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 21 (2019) Issue 3 Article 2 Remnants of Dissent Thomas Docherty University of Warwick, UK Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Docherty, Thomas. "Remnants of Dissent." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 21.3 (2019): <https://doi.org/ 10.7771/1481-4374.3545> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2014 Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power Majken Jul Sorensen University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Sorensen, Majken Jul, Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2014. -

Speaking Truth to Power the

1 Speaking Truth to Power The Methods of Nonviolent Struggle in Burma by Aurlie Andrieux, Diana Sarosi and Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan 2005 Nonviolence International Use of material within this report is encouraged, with acknowledgement. ISBN 974-93792-5-X www.nonviolenceinternational.net Nonviolence International Southeast Asia Office 104/20 Soi Latprao 124, Wangtonglang, Bangkok 10310 SIAM Tel/Fax: +662 934 3289 | [email protected] SpeakingTruthruth to PowerT The Methods of Nonviolent Struggle in Burma Aurélie Andrieux Diana Sarosi Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan with a foreword by Jody Williams, 1997 Nobel Peace Laureate Nonviolence in Asia Series Number 2 Nonviolence International Southeast Asia SPEAKING T RUTH TO POWER: The Methods of Nonviolent Struggle in Burma THE GOAL OF THIS PUBLICATION is to introduce the general reading public to the methods of strategic nonviolent political struggle and to document examples from a country which endures military rule. The use of active nonviolence is generally only known, vaguely, through human rights reports, when they report on the extraordinarily long prison sentences activists receive when captured. Exactly what means the activists employ, and why they are confident that it will make a difference, and their continued acts of resistance within the prison system, are not generally known. Frequently Burma is only portrayed as a situation of human rights abuse, and clearly abuse of rights by the military authorities is widespread. We were drawn to documenting the depth of the tactics of nonviolence used by activists within Burma, which demonstrate their absolute rejection of military rule, by reading deeply through human rights and news reports produced in large numbers over the past 15 years. -

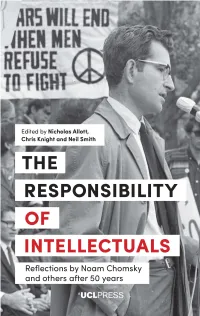

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

The Responsibility of Intellectuals EthicsTheCanada Responsibility and in the FrameAesthetics ofofCopyright, TranslationIntellectuals Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895– 1924 ExploringReflections the by Work Noam of ChomskyAtxaga, Kundera and others and Semprún after 50 years HarrietPhilip J. Hatfield Hulme Edited by Nicholas Allott, Chris Knight and Neil Smith 00-UCL_ETHICS&AESTHETICS_i-278.indd9781787353008_Canada-in-the-Frame_pi-208.indd 3 3 11-Jun-1819/10/2018 4:56:18 09:50PM First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-press Text © Contributors, 2019 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Allott, N., Knight, C. and Smith, N. (eds). The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and others after 50 years. London: UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14324/ 111.9781787355514 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. -

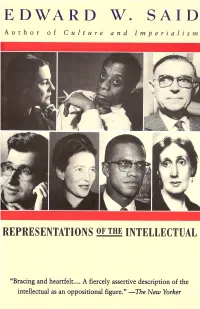

Representations of the Intellectual

Representations of the Intellectual THE 1993 REITH LECTURES Edward W. Said VINTAGE BOOKS A DIVISION OF RANDOM HOUSE, INC. NEW YORK First Vintage Books Edition, April 1996 Copyright © 1994 by Edward W. Said All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in Great Britain in hardcover by Vintage Books (UK), London, in 1994. First published in the United States in hardcover by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1994. The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon edition as follows: Said, Edward W. Representations of the intellectual: the Reith lectures I Edward W. Said. p. cm. ISBN 0-679-43586-7 1. Intellectuals. 2. Intellectuals in literature. I. Title. II. Title: Reith lectures. HM213.S225 1994 305.5'52-<ic20 94-3950 CIP Vintage ISBN: 0-679-76127-6 Book design by Fearn Cutler Printed in the United States of America 9 For Ben Sonnenberg CONTENTS Introduction ix I Representations of the Intellectual 3 II Holding Nations and Traditions at Bay 25 III Intellectual Exile: Expatriates and Marginals 47 IV Professionals and Amateurs 65 V Speaking Truth to Power 85 VI Gods That Always Fail 103 INTRODUCTION THERE IS NO equivalent fo r the Reith Lectures in the United States, although several Americans, Robert Op penheimer, John Kenneth Galbraith, John Searle, have de livered them since the series was inaugurated in 1948 by Bertrand Russell. -

Speaking Truth to Power? Theorizing Whistleblowing

the editors 2016 ISSN 1473-2866 (Online) ISSN 2052-1499 (Print) www.ephemerajournal.org Invitation for an ephemera workshop on: Speaking truth to power? Theorizing whistleblowing Organizers: Kate Kenny and Meghan Van Portfliet Date: 14 December 2016 Location: Queen’s University Belfast This workshop explores the relation between whistleblowing and forms of organizational power, and with critique. With the shocking revelations of Snowden and Wikileaks, and news of Manning’s mistreatment in custody, whistleblowing is a ‘hot topic’ in news debates. Even so, public perceptions of whistleblowers are rife with ambivalence; for some they represent ‘traitorous violators’ of a code of fidelity to their organization, suspicious figures who reject their obligations of loyalty to the employer, and dangerous tellers of secrets. Others view whistleblowers as heroes: martyrs to the cause of transparency and openness and the veritable ‘saints’ of today’s secular culture (Grant, 2002). Where is organization theory in this? Specifically, how can we conceptualize the variable ways in which whistleblowing intersects with, challenges, and/ or reinforces structures of power and domination in today’s organizations? Organizational research into this area tends to be somewhat a-political, evaluating whistleblowing in terms of whether predefined rules defining employee disclosures have been followed. Studies in the field range from predicting the likelihood of whistleblowing occurring in a given organizational setting (Bjørkelo et al., 2010; Miceli, 2004), and creating typologies of motivations for why people speak up, to studying whistleblowing as an ongoing process rather than a one-off event and examining the kinds of retaliations and personal impacts that organizational whistleblowers suffer call for papers | 1 (Alford, 2001; Glazer and Glazer, 1989).