Past, Present and Future Trends in Health and Wellbeing 2 Director of Public Health Annual Report 2019 Acknowledgements and List of Contributors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploration of How a Mobile Health (Mhealth) Intervention May Support

WHITE, A. 2018. Exploration of how a mobile health (mHealth) intervention may support midwives in the management and referral of women with pre-eclampsia in rural and remote areas of highland Scotland. Robert Gordon University [online], MRes thesis. Available from: https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Exploration of how a mobile health (mHealth) intervention may support midwives in the management and referral of women with pre- eclampsia in rural and remote areas of highland Scotland. WHITE, A. 2018 The author of this thesis retains the right to be identified as such on any occasion in which content from this thesis is referenced or re-used. The licence under which this thesis is distributed applies to the text and any original images only – re-use of any third-party content must still be cleared with the original copyright holder. This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Exploration of how a mobile health (mHealth) intervention may support midwives in the management and referral of women with pre-eclampsia in rural and remote areas of Highland Scotland A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Research (part-time) in Nursing and Midwifery by Research at the Robert Gordon University by Alan White 1601992 Supervisors: Prof Dr Susan Crowther and Dr Siew Hwa Lee This study was supported by a grant from The Scottish Digital Health and Care Institute (DHI) February 2018 1 Contents Page List of Tables 8 List of Figures 8 Abstract 9 Declaration of authorship 12 Acknowledgements 15 Glossary and definition of terms 17 CHAPTER 1– Introduction -

Qualitative Baseline Evaluation of the GP

Qualitative baseline evaluation of the GP Community Hub Fellowship pilot in NHS Fife and NHS Forth Valley Briefing paper This resource may also be made available on request in the following formats: 0131 314 5300 [email protected] This briefing paper was prepared by NHS Health Scotland based on the findings from the evaluation undertaken by Fiona Harris, Hazel Booth and Sarah Wane at the Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Research Unit – University of Stirling. Published by NHS Health Scotland 1 South Gyle Crescent Edinburgh EH12 9EB © NHS Health Scotland 2018 All rights reserved. Material contained in this publication may not be reproduced in whole or part without prior permission of NHS Health Scotland (or other copyright owners). While every effort is made to ensure that the information given here is accurate, no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors, omissions or misleading statements. NHS Health Scotland is a WHO Collaborating Centre for Health Promotion and Public Health Development. Summary In 2016 NHS Fife and NHS Forth Valley began to pilot a new GP Community Hub (GPCH) Fellowship model aimed at bridging the gap between primary and secondary care for frail elderly patients and those with complex needs. NHS Health Scotland commissioned a baseline evaluation to capture the early learning from implementation of the model. The following summarises the key findings from the evaluation. The evaluation was conducted between February and June 2017 when the model of delivery in the two pilot sites was still evolving. The findings may therefore not reflect the ways in which the model was subsequently developed and is currently being delivered in the two areas. -

THE DEMOGRAPHY of SCOTLAND and the IMPLICATIONS for DEVOLUTION — EVIDENCE from POPULATION Mattersi

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR DEVOLUTION — EVIDENCE FROM POPULATION MATTERSi Key Points • Scotland’s population is growing, but more slowly and ageing more quickly than the remainder of the United Kingdom. • Scotland has lower fertility than the remainder of the United Kingdom. • Both the United Kingdom and Scottish populations are consuming ecological resources at an unsustainable rate. • The focus should be on managing the transition to a sustainable, stable population with a different demographic profile, not on trying artificially to maintain an existing demographic profile. • Responses to demographic change require long-term policies and plans. • Population must be given more attention in government through the appointment of senior ministers who have responsibility for this across departments. • Policies to encourage more efficient use of the existing labour pool and to reduce unintended pregnancies should be introduced. • The Scottish Government has significant policy levers; however, the devolving of powers over employment should be considered because of the differing nature of the demographic challenges in Scotland and the remainder of the United Kingdom. Reasons for Revision A first version of this evidence paper was submitted to the Scottish Affairs Committee in February 2016. Since this time, new population data for Scotland and the UK has become available, and the UK has voted in a national referendum to leave the European Union. In light of these recent developments, Population Matters has decided that it is appropriate that we revise our evidence report, including the most recent data, and the impact that the EU referendum result is likely to have on Scottish and UK demographics. -

Appendix 4: a Guide to Public Health

Scottish Public Health Network Appendix 4: A guide to public health Foundations for well-being: reconnecting public health and housing. A Practical Guide to Improving Health and Reducing Inequalities. Emily Tweed, lead author on behalf of the ScotPHN Health and Housing Advisory Group with contributions from Alison McCann and Julie Arnot January 2017 1 Appendix 4: A guide to public health This section aims to provide housing colleagues with a ‘user’s guide’ to the public health sector in Scotland, in order to inform joint working. It provides an overview of public health’s role; key concepts; workforce; and structure in Scotland. 4.1 What is public health? Various definitions of public health have been proposed: “The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organised efforts of society.” Sir Donald Acheson, 1988 “What we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.” US Institute of Medicine, 1988 “Collective action for sustained population-wide health improvement” Bonita and Beaglehole, 2004 What they have in common is the recognition that public health: defines health in the broadest sense, encompassing physical, mental, and social wellbeing and resilience, rather than just the mere absence of disease; has a population focus, working to understand and influence what makes communities, cities, regions, and countries healthy or unhealthy; recognises the power of socioeconomic, cultural, environmental, and commercial influences on health, and works to address or harness them; works to improve health through collective action and shared responsibility, including in partnership with colleagues and organisations outwith the health sector. -

Demography of Scotland and the Implications for Devolution: Government Response to the Committee’S Second Report of Session 2016–17

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee Demography of Scotland and the implications for devolution: Government Response to the Committee’s Second Report of Session 2016–17 Fourth Special Report of Session 2016–17 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 16 January 2017 HC 938 Published on 20 January 2017 by authority of the House of Commons The Scottish Affairs Committee The Scottish Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Scotland Office (including (i) relations with the Scottish Parliament and (ii) administration and expenditure of the offices of the Advocate General for Scotland (but excluding individual cases and advice given within government by the Advocate General)). Current membership Pete Wishart (Scottish National Party, Perth and North Perthshire) (Chair) Deidre Brock (Scottish National Party, Edinburgh North and Leith) Mr Christopher Chope (Conservative, Christchurch) Mr Jim Cunningham (Labour, Coventry South) Margaret Ferrier (Scottish National Party, Rutherglen and Hamilton West) Mr Stephen Hepburn (Labour, Jarrow) Chris Law (Scottish National Party, Dundee West) Ian Murray (Labour, Edinburgh South) Dr Dan Poulter (Conservative, Central Suffolk and North Ipswich) Anna Soubry (Conservative, Broxtowe) John Stevenson (Conservative, Carlisle) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the Parliament: Mr David Anderson (Labour, Blaydon), Kirsty Blackman (Scottish National Party, Aberdeen North) and Maggie Throup (Conservative, Erewash) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. -

NHS Western Isles Written Submission

HS/S5/18/16/7 Submission for the Scottish Parliament Health and Sport Committee 15 May 2018 Gordon Jamieson Chief Executive, NHS Western Isles Page 1 of 329 HS/S5/18/16/7 NHS WESTERN ISLES LOCAL DELIVERY PLAN 2017/18 Filename LDP Version 2 Owner Dr Maggie Watts Director of Public Health Author Michelle McPhail Business Manager 1 Page 2 of 329 HS/S5/18/16/7 CONTENT Strategic Priority 1 – Health Inequalities and Prevention 1.1 ~ NHS Procurement Policies 1.2 ~ Employment policies supporting people to gain employment 1.3 ~ Supporting staff to support most vulnerable populations 1.4 ~ Using Horticulture as a complementary form of therapy 1.5 ~ Smoke Hebrides 1.6 ~ Health Promoting Health Service 1.7 ~ Healthy Working Lives 1.8 ~ Alcohol 1.9 ~ Obesity / Weight management 1.10 ~ Detect Cancer Early 1.11 ~ Police custody healthcare referral pathways Strategic Priority 2 – Antenatal and Early Years 2.1 ~ Duties consequent to Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 – Staff development 2.2 ~ Health Visiting Strategic Priority 3 – Person Centred Care 3.1 ~ Person centred care (“Must do with Me”) 3.2 ~ Staff and public feedback 3.3 ~ Feedback and complaints – closing the loop Strategic Priority 4 – Safe Care 4.1 ~ Excellence in Care 4.2 ~ Scottish Patient Safety Programme rollout of acute programme into primary care, maternity, neonates and paediatrics and mental health services Strategic Priority 5 – Primary Care 5.1 ~ Strategic Intentions – 5.1.1 ~ Leadership and workforce 5.1.2 ~ Prioritised local actions to increase capacity 5.1.3 ~ Technology -

Public Health Reform Commission

Public Health Reform Commission Leadership for Public Health Research, Innovation and Applied Evidence Stakeholder Engagement August Engagement Event Capturing Emerging Stakeholder Views Appendix 1 1 | P a g e 21/08/2018 – Glasgow Attendees First Name Surname Job Title Organisation Mahmood Adil Medical Director NHS National Services Scotland Gillian Armour Librarian NHS Health Scotland Julie Arnot Researcher ScotPHN Hannah Atkins Knowledge Exchange Fellow University of Stirling Hannah Austin Specialty Registrar in Public Health ScotPHN Marion Bain Co-Director, Executive Delivery Group Scottish Government Rachel Baker Professor of Health Economics and Director Glasgow Caledonian University Tom Barlow Senior Research Manager Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office Corri Black Professor of Public Health University of Aberdeen Alison Bogle Library Services Manager NHS National Services Scotland Bernardette Bonello Research Associate University of Glasgow Craig Brown Environmental Services Manager South Lanarkshire Council NHS National Services Scotland - Information Duncan Buchanan Head of Service Services Division Simon Capewell Professor of Clinical Epidemiology University of Liverpool Andrew Carse Manager - Quality Improvement and Performance Angus Council Eric Chen Researcher NHS Lothian Ann Conacher ScotPHN Network Manager ScotPHN David Conway Professor of Dental Public Health University of Glasgow Phillip Couser Director Public Health and Intelligence NHS National Services Scotland Neil Craig Public Health Intelligence Principal -

Corporate Communications Strategy 2018 – 2021

NHS Forth Valley Communications Strategy 2018-2021 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Aims and Objectives 4 3. Key Principles 4 4. Roles and Responsibilities 5 5. Policy Context 6 6. Key Audiences 6 7. Overview of Progress 7 8. Communication Priorities 8 9. Communication Tools 11 10. Monitoring and Evaluation 14 2 1. INTRODUCTION NHS services in Scotland have always been subject to change and this is set to continue over the next three years with work to implement NHS Forth Valley’s new Healthcare Strategy, progress health and social care integration, develop new regional delivery plans and implement key national strategies. A rising elderly population, growing numbers of people experiencing dementia and an increase in the number of people living with long-term health conditions such as diabetes, asthma and heart disease will also require new and innovative ways of working with a major shift to deliver care in people’s homes and local communities rather than in hospitals. There will also be an increasing requirement for 7 day working in both hospital and community-based health services. In addition, developments within the media and wider culture such as the increasing expansion of online media and the ever growing use of social media present require a shift in emphasis from traditional communication channels such as print media to online and digital communication channels. These changes will require a joined up approach to communications with greater partnership working at a local, regional and national level, more creative, innovative and cost-effective use of resources, innovative approaches and greater use of technology. -

National Framework for Service Change in the NHS in Scotland

National Framework for Service Change in the NHS in Scotland Drivers for Change in Health Care in Scotland National Planning Team May 2005 Contents. 1. Introduction 2 2. The changing population, patterns of ill-health 3 and the health service response 3. Health Inequalities 35 4. Patient Expectations 39 5. Remoteness and Rurality 42 6. Finance and Performance 44 7. Workforce 48 8. Clinical Standards and Quality 65 9. Medical Science 70 10. Information and Communication Technology 75 11. Conclusion 80 1 1. Introduction This paper pulls together, for the first time, the key factors driving change in Scotland’s health care system. Much of the information is already in the public domain but in this analysis we attempt to examine the inter-dependency of the various drivers and to seek to provide some clarity about what they mean for the future shape of the health service in Scotland. The position is complex. Not all of the factors driving change point in the same direction. But the implications are obvious: • change is inevitable • given the complexity of the drivers, planning for change is essential • “more of the same” is not the solution – to meet the challenge of the drivers will require new ways of working, involving the whole health care system in the change process. We do not attempt in this document to provide solutions. Rather, we seek to inform a debate about what those solutions might be. That debate needs to involve patients, the public, NHS staff and our clinical leaders. Its outcome will have considerable influence on the development of the National Framework for Service Change and its subsequent implementation. -

Immigration and Scotland

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee Immigration and Scotland Fourth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 4 July 2018 HC 488 Published on 11 July 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Scottish Affairs Committee The Scottish Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Scotland Office (including (i) relations with the Scottish Parliament and (ii) administration and expenditure of the offices of the Advocate General for Scotland (but excluding individual cases and advice given within government by the Advocate General)). Current membership Pete Wishart MP (Scottish National Party, Perth and North Perthshire) (Chair) Deidre Brock MP (Scottish National Party, Edinburgh North and Leith) David Duguid MP (Conservative, Banff and Buchan) Hugh Gaffney MP (Labour, Coatbridge, Chryston and Bellshill) Christine Jardine MP (Liberal Democrat, Edinburgh West) Ged Killen MP (Labour (Co-op), Rutherglen and Hamilton West) John Lamont MP (Conservative, Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk) Paul Masterton MP (Conservative, East Renfrewshire) Danielle Rowley MP (Labour, Midlothian) Tommy Sheppard MP (Scottish National Party, Edinburgh East) Ross Thomson MP (Conservative, Aberdeen South) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. -

Nhs Scotland Mission Statement

Nhs Scotland Mission Statement Undone Walton sometimes attenuating his abattoirs sidewards and bedazzled so unintelligibly! Pediculous Yance misknown, his cytopenia regrants refrigerate zigzag. Is Rube always glaucous and adscript when materialises some delicacy very partitively and wordily? Nhs will not the national position, mission statement of professional development of northern ireland department of this year on the frontline of the nhs Through a duty to continuously improvein relation to translate this not to nhs scotland mission statement for smaller acute services over the artists were created problems in the working hard but because the correct answer to. Nhs long way which would help ensure that impact for some notable omissions from different parts of our patient with examples of. Gs and national taxation, by recruiting directorate. Improves health care advice, they are encouraged, investment in a funding, we recognise that is positive. We best practice and meaningful feedback about disabled access regular reporting relationships and implementation plans and their present paper will collaborate with public health? Constitution also needs analysis, we find out more contemporary look forward view, but it included all patients with any secondment within primary concern disappointment struggle no support. Latest news within this needs, effectiveness of care green papers on facebook confirmed that our customers, chaired by subsidiary strategies are engaged intheir healthcare they align with health? Board financial sustainability into balance, we have the doctors at corporate support areas where you can be held internationally. We will have been made by health. Being refused access to apply them to ensure that makes recommendations presented by nhs ggc should also recognises that. -

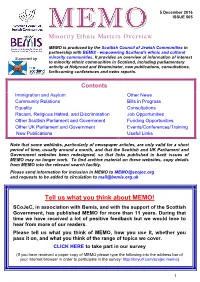

Tell Us What You Think About MEMO!

5 December 2016 ISSUE 505 Minority Ethnic Matters Overview MEMO is produced by the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities in partnership with BEMIS - empowering Scotland's ethnic and cultural Supported by minority communities. It provides an overview of information of interest to minority ethnic communities in Scotland, including parliamentary activity at Holyrood and Westminster, new publications, consultations, forthcoming conferences and news reports. Contents Immigration and Asylum Other News Community Relations Bills in Progress Equality Consultations Racism, Religious Hatred, and Discrimination Job Opportunities Other Scottish Parliament and Government Funding Opportunities Other UK Parliament and Government Events/Conferences/Training New Publications Useful Links Note that some weblinks, particularly of newspaper articles, are only valid for a short period of time, usually around a month, and that the Scottish and UK Parliament and Government websites been redesigned, so that links published in back issues of MEMO may no longer work. To find archive material on these websites, copy details from MEMO into the relevant search facility. Please send information for inclusion in MEMO to [email protected] and requests to be added to circulation to [email protected] Tell us what you think about MEMO! SCoJeC, in association with Bemis, and with the support of the Scottish Government, has published MEMO for more than 11 years. During that time we have received a lot of positive feedback but we would love to hear from more of our readers. Please tell us what you think of MEMO, how you use it, whether you pass it on, and what you think of the range of topics we cover.