“Public Spaces of Memory Contested Visualizations of Absence in Cairo”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiin Wo 2011/161427 A3 Wo 2011/161427

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIN (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2011/161427 A3 29 December 2011 (29.12.2011) PCT (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 38/17 (2006.01) A61P 5/50 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61P 3/10 (2006.01) A61P 21/00 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A61P 3/04 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, PCT/GB2011/000966 KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (22) International Filing Date: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 27 June 2011 (27.06.2011) NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (25) Filing Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 61/358,596 25 June 2010 (25.06.2010) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, 61/384,652 20 September 2010 (20.09.2010) US ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, 61/420,677 7 December 2010 (07.12.2010) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): ASTON LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, UNIVERSITY [GB/GB]; Aston Triangle, Birmingham SM, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, B4 7ET (GB). -

UFC) Started in 1993 As a Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) Tournament on Pay‐Per‐View to Determine the World’S Greatest Martial Arts Style

Mainstream Expansion and Strategic Analysis Ram Kandasamy Victor Li David Ye Contents 1 Introduction 2 Market Analysis 2.1 Overview 2.2 Buyers 2.3 Fighters 2.4 Substitutes 2.5 Complements 3 Competitive Analysis 3.1 Entry 3.2 Strengths 3.3 Weaknesses 3.4 Competitors 4 Strategy Analysis 4.1 Response to Competitors 4.2 Gymnasiums 4.3 International Expansion 4.4 Star Promotion 4.5 National Television 5 Conclusion 6 References 1 1. Introduction The Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) started in 1993 as a mixed martial arts (MMA) tournament on pay‐per‐view to determine the world’s greatest martial arts style. Its main draw was its lack of rules. Weight classes did not exist and rounds continued until one of the competitors got knocked out or submitted to his opponent. Although the UFC initially achieved underground success, it was regarded more as a spectacle than a sport and never attained mainstream popularity. The perceived brutality of the event led to political scrutiny and pressure. Attacks from critics caused the UFC to establish a set of unified rules with greater emphasis placed on the safety. The UFC also successfully petitioned to become sanctioned by the Nevada State Athletic Commission. However, these changes occurred too late to have an impact and by 2001, the parent organization of the UFC was on the verge of bankruptcy. The brand was sold to Zuffa LLC, marking the beginning of the UFC’s dramatic rise in popularity. Over the next eight years, the UFC evolved from its underground roots into the premier organization of a rapidly growing sport. -

SWT Housing Newsletter 2020

WINTER 2020 Housing News Great Homes for Local Communities Introduction from Cllr Francesca Smith (Housing Portfolio Holder) Welcome to our December issue of the Somerset West and Taunton Housing Newsletter. Going forward we intend to produce a newsletter for you to read every quarter. The next one will be due in spring and you can also find this newsletter online at www.somersetwestandtaunton.gov.uk. We have all been through so much this year, especially with lockdowns during the year. Just as we were gaining momentum after the first lockdown, we had to lock down again. We will of course continue to support our residents during the global pandemic and reduce the risk of spreading the coronavirus. Despite, the difficulties this year, the Housing Directorate has continued to deliver against their objectives of delivering more new homes, providing great customer services and improving our existing homes and neighbourhoods. I hope you enjoy reading about the great things that have been achieved in this edition. The future of Local Government still remains subject to change and I wrote to you in November to make you aware of those changes. You may wish to look through the “Stronger Somerset” (www. strongersomerset.co.uk) and “One Council” (www.onesomerset.org.uk) information to familiarise yourself with the current situation. Lastly but certainly not least “I wish you all a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!” Annual Report 2019/2020 Highlights 83% of our Deane Helpline Our Debt & customers rated the service Benefit Advisor they received as excellent helped 444 tenants We spent 7.9 million repairing, maintaining and We completed 41 major improving your homes and disability adaptations and communal areas. -

Church Directory

Commonwealth Journal Wednesday, May 9, 2012 Somerset, Kentucky A9 Price Heating & Air Cumberland Restoration This Compliments of SOMERSET When Minutes Count and Quality Matters directory Commercial • Residential NURSING & License M00698 is made 206 Allen Drive Cumberland possible by REHABILITATION Somerset, KY 42503 these FACILITY (606) 679-4569 Restoration businesses Fax: (606) 679-5729 43 Jacks Lane who 4195 S.Hwy. 27, Somerset, KY 42503 Cell: (606) 219-5286 Somerset, KY 42501 encourage all 106 Gover St Res.: (606) 679-4569 to attend 606-679-1601 Carl Price 606-678-2690 worship 679-8331 Carl & Dottie Price Brittany Price Hamilton (FAX) 606-678-4847 www.toyotaofsomerset.com Owners Office Manager services All Season Construction HURCH IRECTORY & Remodeling C D INSTALLING PEACE OF MIND Additions, Garages, Decks, Windows, NOBODY WARRANTIES LIKE TIRE PROS Siding, Doors, Kitchens, Baths, CHURCH OF CHRIST CHURCH OF GOD NAZARENE SOMERSET Roofs & More Across from Somerset Mall Steve Pittman FAIRVIEW CHURCH OF CHRIST VALLEY VIEW LAKE CUMBERLAND Owner/Operator Off Ky. 70 CHURCH OF GOD 151 East Oak Hill Road 4285 South U.S. 27 Somerset, Kentucky Willailla, Ky. 129 Hyatts Ford Road Somerset – 678-4070 Somerset, Ky. Phone: 606-383-2318 Science Hill, Ky. – 606-423-2368 NAOMI CHURCH NAZARENE GOOCHTOWN CHURCH 64 Daws Ridge, Nancy – 871-7656 606-451-3137 Licensed • Insured OF CHRIST WORLDWIDE CHURCH OF GOD SCIENCE HILL Goochtown Road, Eubank, Ky. Carl Fields – 423-3272 Stanford St., Science Hill – 423-2227 Victory Christian HAZELDELL CHURCH SPIRIT & TRUTH OF CHRIST EPISCOPAL COMMUNITY CENTER 1399 Ocala Road 15 Fairdale Drive Fellowship ST. PATRICK EPISCOPAL Somerset, Ky. -

SALT LAKE CITY HISTORIC LANDSCAPES REPORT Executive Summary

SALT LAKE CITY HISTORIC LANDSCAPES REPORT Executive Summary Warms Springs Park SLCHLR NO. 26 Warm Springs Park is located within the Capitol Hill National Historic District in Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County, Utah. It fronts on Beck Street (300 West) and Wall Street at 840 North Beck Street. The Warm Springs Park landscape is not considered historic in and of itself; however, it has historic significance because of the recognition of the area encompassing the historic warm springs; and its association with past building site(s) including the original 1922 Warm Springs Municipal Bathhouse located directly to the north. Warm Springs Park was established as a neighborhood park in 1925. The nine-acre park is bordered by Beck Street to the west, Wall Street to the southwest, Victory Road to the east, the historic warm springs site and North Gateway Park to the north, and an electrical substation to the south. The park site is relatively flat, nestled into the lower slopes of West Capitol Hill. Victory Road is several stories higher than the park site, tracing the terrain of the hill. A mix of commercial and light industrial uses are located on the opposite side of Beck Street, with a mix of single-family and higher-density residential uses dominating the Wall Street environment and neighborhoods to the south. There are numerous historic residences in the vicinity of the park particularly to the south. The park is accessed from Beck Street (300 West) and Wall Street. The park is divided into three character-defining sections: Northern Entrance & Tennis Courts, Open Park and Southern Entrance & Playground. -

Media Approved

Film and Video Labelling Body Media Approved Video Titles Title Rating Source Time Date Format Applicant Point of Sales Approved Director Cuts 10,000 B.C. (2 Disc Special Edition) M Contains medium level violence FVLB 105.00 28/09/2010 DVD The Warehouse Roland Emmerich No cut noted Slick Yes 28/09/2010 18 Year Old Russians Love Anal R18 Contains explicit sex scenes OFLC 125.43 21/09/2010 DVD Calvista NZ Ltd Max Schneider No cut noted Slick Yes 21/09/2010 28 Days Later R16 Contains violence,offensive language and horror FVLB 113.00 22/09/2010 Blu-ray Roadshow Entertainment Danny Boyle No cut noted Awaiting POS No 27/09/2010 4.3.2.1 R16 Contains violence,offensive language and sex scenes FVLB 111.55 22/09/2010 DVD Universal Pictures Video Noel Clarke/Mark Davis No cut noted 633 Squadron G FVLB 91.00 28/09/2010 DVD The Warehouse Walter E Grauman No cut noted Slick Yes 28/09/2010 7 Hungry Nurses R18 Contains explicit sex scenes OFLC 99.17 08/09/2010 DVD Calvista NZ Ltd Thierry Golyo No cut noted Slick Yes 08/09/2010 8 1/2 Women R18 Contains sexual references FVLB 120.00 15/09/2010 DVD Vendetta Films Peter Greenaway No cut noted Slick Yes 15/09/2010 AC/DC Highway to Hell A Classic Album Under Review PG Contains coarse language FVLB 78.00 07/09/2010 DVD Vendetta Films Not Stated No cut noted Slick Yes 07/09/2010 Accidents Happen M Contains drug use and offensive language FVLB 88.00 13/09/2010 DVD Roadshow Entertainment Andrew Lancaster No cut noted Slick Yes 13/09/2010 Acting Shakespeare Ian McKellen PG FVLB 86.00 02/09/2010 DVD Roadshow Entertainment -

Pro Wrestling Over -Sell

TTHHEE PPRROO WWRREESSTTLLIINNGG OOVVEERR--SSEELLLL™ a newsletter for those who want more Issue #1 Monthly Pro Wrestling Editorials & Analysis April 2011 For the 27th time... An in-depth look at WrestleMania XXVII Monthly Top of the card Underscore It's that time of year when we anything is responsible for getting Eddie Edwards captures ROH World begin to talk about the forthcoming WrestleMania past one million buys, WrestleMania, an event that is never it's going to be a combination of Tile in a shocker─ the story that makes the short of talking points. We speculate things. Maybe it'll be the appearances title change significant where it will rank on a long, storied list of stars from the Attitude Era of of highs and lows. We wonder what will wrestling mixed in with the newly Shocking, unexpected surprises seem happen on the show itself and gossip established stars that generate the to come few and far between, especially in the about our own ideas and theories. The need to see the pay-per-view. Perhaps year 2011. One of those moments happened on road to WreslteMania 27 has been a that selling point is the man that lit March 19 in the Manhattan Center of New York bumpy one filled with both anticipation the WrestleMania fire, The Rock. City. Eddie Edwards became the fifteenth Ring and discontent, elements that make the ─ So what match should go on of Honor World Champion after defeating April 3 spectacular in Atlanta one of the last? Oddly enough, that's a question Roderick Strong in what was described as an more newsworthy stories of the year. -

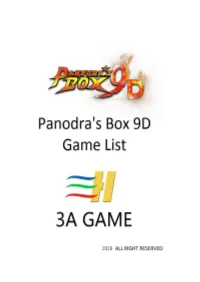

Pandoras Box 9D Arcade Versi

PAGE 1 PAGE 6 1 The King of Fighters 97 51 Cth2003 2 The King of Fighters 98 52 King of Fighters 10Th Extra Plus 3 The King of Fighters 98 Combo Hot 53 Marvel SuperHeroes 4 The King of Fighters 99 54 Marvel Vs. Street Fighter 5 The King of Fighters 2000 55 Marvel Vs. Capcom:Clash 6 The King of Fighters 2001 56 X-Men:Children of the Atom 7 The King of Fighters 2002 57 X-Men Vs. Street Fighter 8 The King of Fighters 2003 58 Street Fighter Alpha:Dreams 9 King of Fighters 10Th UniqueII 59 Street Fighter Alpha 2 10 Cth2003 Super Plus 60 Street Fighter Alpha 3 PAGE 2 PAGE 7 11 The King of Fighters 97 Training 61 Super Gem Fighter:Mini Mix 12 The King of Fighters 98 Training 62 Ring of Destruction II 13 The King of Fighters 98 Combo Training 63 Vampire Hunter:Revenge 14 The King of Fighters 99 Training 64 Vampire Hunter 2:Revenge 15 The King of Fighters 2000 Training 65 Slam Masters 16 The King of Fighters 2001 Training 66 Street Fighter Zero 17 The King of Fighters 2002 Training 67 Street Fighter Zero2 18 The King of Fighters 2003 Training 68 Street Fighter Zero3 19 SNK Vs. Capcom Super Plus 69 Vampire Savior:Lord of Vampire 20 King of Fighters 2002 Magic II 70 Vampire Savior2:Lord of Vampire PAGE 3 PAGE 8 21 King of Gladiator 71 Vampire:The Night Warriors 22 Garou:Mark of the Wolves 72 Galaxy Fight:Universal Warriors 23 Samurai Shodown V Special 73 Aggressors of Dark Kombat 24 Rage of the Dragons 74 Karnodvs Revenge 25 Tokon Matrimelee 75 Savage Reign 26 The Last Blade 2 76 Tao Taido 27 King of Fighters 2002 Super 77 Solitary Fighter 28 King -

2018 03/21 CHNC Minutes DRAFT

Capitol Hill Neighborhood Council Meeting Minutes 3/21/18 6:30 Marmalade Library Multipurpose Room Welcome - Laura Arellano Introduction of volunteer board and committees, reminder of mission to foster a participatory community of informed, engaged, and empower residents. Approval of February Minutes (Motion to approve GS, Seconded DH, Unanimously approved) Representative Reports Chris Valdez, Fire Station 2 • Residents can now subscribe to the newsletter on slcfire.com/contact. • Hiring process deadline on 3/31 with test in April, requirements on slcfire.com. • Spring cleanup reminders to check smoke detectors and change batteries, use website for resources on potential hoarding because clean-up won’t solve underlying health concerns. • A Captain is retiring who was instrumental to the heavy rescue team. • Station 2 remains the busiest station with calls returning to original levels after slight dip from Operation Rio Grande. Detective Alen Gibic, SLCPD • Victory Road camps will be cleaned up by June 1st per Health Department and City. • Theft of campaign signs (armed) has had no additional victims. • Squad arresting a burglar using city statistics to focus on a single area and time. • Package theft continues, some are caught through operations, but reminder to ship packages somewhere they can be taken in right away. Katherine Kennedy, Salt Lake City School District • SLCSD is midway through budget process and Katherine is wiling to point those interested to resources to follow this online as well as to follow the creation of a district wide orchestra (10K fundraising goal) relative to the needs to support arts for student engagement and broad community interest. -

3390 in 1 Games List

3390 in 1 Games List www.arcademultigamesales.co.uk Game Name Tekken 3 Tekken 2 Tekken Street Fighter Alpha 3 Street Fighter EX Bloody Roar 2 Mortal Kombat 4 Mortal Kombat 3 Mortal Kombat 2 Gear Fighter Dendoh Shiritsu Justice gakuen Turtledove (Chinese version) Super Capability War 2012 (US Edition) Tigger's Honey Hunt(U) Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Dual Heroes Killer Instinct Gold Mace - The Dark Age War Gods WWF Attitude Tom and Jerry in Fists of Furry 1080 Snowboarding Big Mountain 2000 Air Boarder 64 Tony Hawk's Pro Skater Aero Gauge Carmageddon 64 Choro Q 64 Automobili Lamborghini Extreme-G Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 Mario Kart 64 San Francisco Rush - Extreme Racing V-Rally Edition 99 Wave Race 64 Wipeout 64 All Star Tennis '99 Centre Court Tennis Virtual Pool 64 NBA Live 99 Castlevania Castlevania: Legacy of 1 Darkness Army Men - Sarge's Heroes Blues Brothers 2000 Bomberman Hero Buck Bumble Bug's Life,A Bust A Move '99 Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko Ms. Pac-Man Maze Madness O.D.T (Or Die Trying) Paperboy Rampage 2 - Universal Tour Super Mario 64 Toy Story 2 Aidyn Chronicles Charlie Blast's Territory Perfect Dark Star Fox 64 Star Soldier - Vanishing Earth Tsumi to Batsu - Hoshi no Keishousha Asteroids Hyper 64 Donkey Kong 64 Banjo-Kazooie The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time The King of Fighters '97 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Combo Practice The King of Fighters -

Treasure Valley Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) Strategic Plan

Treasure Valley Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) Strategic Plan September 2006 Prepared By: McFarland Management, LLC In Association With: ~ Treasure Valley ITS Strategic Plan ~ Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................................ES-1 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Purpose..................................................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.3 Potential Benefits of Intelligent Transportation Systems ........................................................................... 1-3 1.4 Participants................................................................................................................................................ 1-4 1.5 Report Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 1-5 2. Existing Conditions............................................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Historical Perspective............................................................................................................................... -

Arbiter, April 3 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 4-3-2006 Arbiter, April 3 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. ISSUE 52 FIRST ISSUE FREE THE I N 0 E PEN 0 E N T STU 0 E N T V 0 I-C E 0 F e 0 I S EST" T E SIN C E 19 3 3 VOLoUHE 18 HONO"Y "PRILo 3 2006 NEWS PAGE 3 Pills like Adderall are becoming the wrong kind of study habit Everyone has an HIV status OPINION PAGE 5 Sex in the classroom: The pro's and con's of procreation education CULTURE ---------------------------~ PAGE 7 . Sick of long hair? Cut the crop. SPORTS ---------------------------- PAGE 12 Long-distance runner Rebecca Guyette prevails In the 5000 meter and leads the BSU track and field teams to victory ONLINE ---------------------------- Post your comments online at: WWW.ARBITERONLINE.COM Protecting ON CAMPUS your sexual condition isn't as difficult as it was health ---------------------------- BY CHAD MENDENHALL don't know ifthey have mv," Malcolm said, MONDAY "It's important to know."· The Center for years ago arid patients are able en- . News Writer On Friday, April 14 2006 Final Four Indianapolis Disease Control and Prevention said they es- joy their lives.