In 2005, When Photographer Rian Dundon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

INTEGRATED SAFEGUARDS DATA SHEET IMPLEMENTATION STAGE . Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 135491 . Date ISDS Prepared/Updated: 18-Dec-2018 I. BASIC INFORMATION 1. Basic Project Data Country: China Project ID: P153115 Project Name: Hunan Integrated Management of Agricultural Land Pollution Project (P153115) Task Team Leader(s): Wendao Cao Board Approval Date: 22-Aug-2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Managing Unit: GEN2A Is this project processed under OP 8.50 (Emergency Recovery) or OP No 8.00 (Rapid Response to Crises and Emergencies)? Project Financing Data (in USD Million) Total Bank Total Project Cost: 111.94 100.00 Financing: Financing Gap: 0.00 Financing Source Amount Borrower 11.94 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 100.00 Public Disclosure Authorized Total 111.94 Environmental Category: A - Full Assessment Is this a Repeater project? No Is this a Transferred No project? . 2. Project Development Objective(s) The project development objective is to demonstrate a risk-based integrated approach to managing heavy metal pollution in agricultural lands for safety of agricultural production areas in selected Public Disclosure Authorized counties in Hunan. 3. Project Description Component 1: Demonstration of Risk-based Agricultural Land Pollution Management. This component aims to demonstrate the risk-based approach to reducing heavy metal levels, notably Cd, in crops and soil at demonstration areas. It will finance implementation of site-specific demonstration plans (to be approved by local agricultural bureaus) -

Hunan Lingjintan Hydropower Project (Loan 1318-PRC) in the People’S Republic of China

Performance Evaluation Report PPE: PRC 26198 Hunan Lingjintan Hydropower Project (Loan 1318-PRC) in the People’s Republic of China December 2005 Operations Evaluation Department Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) At Appraisal At Project Completion At Operations Evaluation (September 1994) (August 2003) (September 2005) CNY1.00 = $0.1149 = $0.1205 = $0.1238 $1.00 = CNY8.70 = CNY8.30 = CNY8.08 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADTA – advisory technical assistance BOO – build-operate-own BOT – build-operate-transfer EA – Executing Agency EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return GWh – gigawatt-hour HEPC – Hunan Electric Power Company HPEPB – Hunan Province Electric Power Bureau IA – Implementing Agency MW – megawatt OED – Operations Evaluation Department, Asian Development Bank OEM – operations evaluation mission PCR – project completion report PPA – power purchase agreement PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance PRC – People’s Republic of China SES – special evaluation study SSTA – small-scale technical assistance TA – technical assistance WACC – weighted and average cost of capital WPC – Wuling Power Corporation NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government ends on 31 December. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Director D. Edwards, Operations Evaluation Division 2, OED Team Leader R. Schenck, Evaluation Specialist, Operations Evaluation Division 2, OED Team Members B. Palacios, Senior Evaluation Officer, Operations Evaluation Division 2, OED A. SIlverio, Operations Evaluation Assistant, Operations Evaluation Division 2,OED Operations Evaluation Department, PE-677 CONTENTS Page BASIC DATA iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iv MAP vii I. -

The Urban Flood Control Project in the Mountainous Area in Hunan Province Loaned by the Asian Development Bank

The Urban Flood Control Project in the Mountainous Area in Hunan Province Loaned by the Asian Development Bank The External Resettlement Monitoring & Assessment Report (Lengshuijiang City, Lianyuan City, Shuangfeng County, Shaoyang City, Shaodong County, Longhui County, Jiangyong County, Xintian County, Jianghua County, Qiyang County, Ningyuan County, Chenzhou City, Zhuzhou City, Liling City, Zhuzhou County and Youxian County) No.1, 2008 Total No. 1 Hunan Water & Electricity Consulting Corporation (HWECC) September, 2008 Approved by: Wang Hengyang Reviewed by: Long Xiachu Prepared by: Long Xiachu, Wei Riwen 2 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Project Outline 2.1 Project Outline 2.2 Resettlement Outline 3. Establishment and Operation of Resettlement Organizations 3.1 Organization Arrangement 3.2 Organization Operation 4. Project Implementation Progress 4.1 Jiangyong County 4.2 Chenzhou City 5. Resettlement Implementation Progress 5.1 Resettlement Implementation Schedule 5.2 Resettlement Policy and Compensation Standards 5.3 Progress of Land Acquisition 5.4 Progress of Resettlement Arrangement 5.5 Removal Progress of Enterprises and Institutions 5.6 Progress of Resettlement Area Construction 5.7 Arrival and Payment of the Resettlement Fund 6. Psychology and Complaint of the Resettled People 6.1 Complaint Channel 6.2 Complaint Procedures 7. Public Participation, Consultation and Information Publicizing 7.1 Jiangyong County 7.2 Chenzhou City 8. Existed Problems and Suggestions 3 1. Introduction The Urban Flood Control Project in the Mountainous -

Environmental Impact Analysis in This Report

Environmental Impacts Assessment Report on Project Construction Project name: European Investment Bank Loan Hunan Camellia Oil Development Project Construction entity (Seal): Foreign Fund Project Administration Office of Forestry Department of Hunan Province Date of preparation: July 1st, 2012 Printed by State Environmental Protection Administration of China Notes for Preparation of Environmental Impacts Assessment Report on Project Construction An Environmental Impacts Assessment (EIA) Report shall be prepared by an entity qualified for conducting the work of environmental impacts assessment. 1. Project title shall refer to the name applied by the project at the time when it is established and approved, which shall in no case exceed 30 characters (and every two English semantic shall be deemed as one Chinese character) 2. Place of Construction shall refer to the detailed address of project location, and where a highway or railway is involved, names of start station and end station shall be provided. 3. Industry category shall be stated according to the Chinese national standards. 4. Total Investment Volume shall refer to the investment volume in total of the project. 5. Principal Targets for Environment Protection shall refer to centralized residential quarters, schools, hospitals, protected culture relics, scenery areas, water sources and ecological sensitive areas within certain radius of the project area, for which the objective, nature, size and distance from project boundary shall be set out as practical as possible. 6. Conclusion and suggestions shall include analysis results for clean production, up-to-standard discharge and total volume control of the project; a determination on effectiveness of pollution control measures; an explanation on environmental impacts by the project, and a clear-cut conclusion on feasibility of the construction project. -

People's Republic of China: Hunan Roads Development III Project

Completion Report Project Number: 37494 Loan Number: 2219 September 2014 People’s Republic of China: Hunan Roads Development III Project This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB's Public Communications Policy 2011. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency unit – yuan (CNY) At Appraisal At Project Completion (15 June 2005) (31 Dec 2012) CNY1.00 = $0.1210 $0.1587 $1.00 = CNY8.2700 CNY6.3026 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMDP – ethnic minority development plan EMP – environmental management plan FIRR – financial internal rate of return GDP – gross domestic product HPTD – Hunan provincial transportation department ICB – international competitive bidding JECC – Hunan Jicha Expressway Construction and Development Co. O&M – operation and maintenance PRC – People’s Republic of China SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment TA – technical assistance WEIGHTS AND MEASURES ha – hectare km – kilometer m2 – square meter m3 – cubic meter mu – Chinese unit of measurement (1 mu = 666.67 m2) pcu – passenger car unit NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars, unless otherwise stated. Vice-President S. Groff, Operations 2 Director General A. Konishi, East Asia Department (EARD) Director H. Sharif, People’s Republic of China Resident Mission (PRCM), EARD Team leader G. Xiao, Senior Project Officer (Transport), PRCM, EARD Team members H. Hao, Project Analyst, PRCM, EARD F. Wang, Senior Project Officer (Financial Management), PRCM, EARD W. Zhu, Senior Project Officer (Resettlement), PRCM, EARD Z. Ciwang, Associate Social Development Officer, PRCM, EARD N. Li, Environment Consultant, PRCM, EARD In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

What Makes This Growth Unique Is That It Has Taken Place in a Cloud of Wonder and Kindness and Constant Kickstarts of the Soul

194 Nassau Street Suite 212 PACIFIC Princeton, NJ 08542 Phone: 609.258.3657 Email: [email protected] www.princeton.edu/~pia Newsletter of PrincetonBRIDGES in Asia Spring 2016 THE THAILAND ISSUE: Celebrating 40 years of Princeton in Asia Fellows in the Kingdom of Thailand VOICES FROM THE FIELD: Notes from our Fellows Personal growth has been the most special element of my time in Asia thus far. Deal- ing with the various challenges presented by opaque bureaucracy, occasional incom- petence (both my own and others’), endless layers of sweat, a bout of head lice, inde- scribable traffic, and the isolation inherent to living abroad has made me a more flex- ible and mature person. What makes this growth unique is that it has taken place in a cloud of wonder and kindness and constant kickstarts of the soul. I’m glad that the les- sons I’m learning right now are based not on an affirmation of the ideas I’ve held my entire life but rather a constant desta- bilization of these ideas: that my move- ment forward is contingent upon expand- ing my capacity for negative capability. Cheers to 40 years of PiA fellows in Thailand! Reflecting on her first year in Nan, 2nd year PiA Devin Choudhury fellow Brenna Cameron (Bandon Srisermkasikorn School ‘14-’16) wrote, “Nan makes me come Royal University of Phnom Penh alive and I can’t wait to return to the students who have become my children, coworkers who have Phnom Penh, Cambodia beome like family, and a country that now strangely feels like home.” all of us so different and all of us here be- The principal of my school gave a won- What makes this cause of different reasons, with different derful speech at our school’s graduation expectations, and having different daily re- ceremony. -

Photoinduced Floquet Topological Magnons in a Ferromagnetic

Photoinduced Floquet topological magnons in a ferromagnetic checkerboard lattice Zhiqin Zhang1,a, Wenhui Feng1,a, Yingbo Yao3, Bing Tang1,2* 1 Department of Physics, Jishou University, Jishou 416000, China 2The Collaborative Innovation Center of Manganese-Zinc-Vanadium Industrial Technology, Jishou University, Jishou 416000, China 3 College of Information and Electronic Engineering, Hunan City University, Yiyang 413000,China Keywords: Floquet topological magnons; Topological phase transitions; The Floquet-Bloch theory; Irradiated checkerboard ferromagnets ABSTRACT This theoretical work is devoted to investigating laser-irradiated Floquet topological magnon insulators on a two-dimensional checkerboard ferromagnet and corresponding topological phase transitions. It is shown that the checkerboard Floquet topological magnon insulator is able to be transformed from a topological magnon insulator into another one possessing various Berry curvatures and Chern numbers by changing the light intensity. Especially, we also show that both Tamm-like and topologically protected Floquet magnon edge states can exist when a nontrivial gap opens. In addition, our results display that the sign of the Floquet thermal Hall conductivity is also tunable via varying the light intensity of the laser field. * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: [email protected] a These authors contributed equally to this work. 1. Introduction Up to now, topological insulators have received more and more attention from both theoretical and experimental researchers[1]. Such nontrivial insulators have been realized in a lot of electronic systems, which possess a bulk energy band gap like a common insulator but possess the topologically protected edge (or surface) states because of the bulk-boundary correspondence[2]. Theoretically, the idea of the topological band structure does not depend on the statistical characteristic of the quasiparticle (boson or fermion ) excitations. -

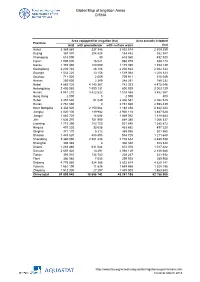

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

A Probe Into the EFL Learning Style Preferences of Minority College Students: an Empirical Study of Tujia EFL Learners in Jishou University

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 2, No. 8, pp. 1662-1667, August 2012 © 2012 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.2.8.1662-1667 A Probe into the EFL Learning Style Preferences of Minority College Students: An Empirical Study of Tujia EFL Learners in Jishou University Feng Liu Faculty of English, College of Literature and Law, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya'an, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—The purpose of this study is to find out the learning style preferences of Tujia EFL learners in Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Xiangxi1 and provide some suggestions for improving effectiveness of College English teaching in Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Xiangxi based on the findings. The findings of the study have both theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, first, the feasibility of the multidimensional questionnaire of learning styles is proved in this empirical study. At the same time, the successful application of the multidimensional learning-styles instrument will help researchers to draw a complete picture of students’ learning style preferences. Second, the present study also found “the ethnic culture and socialization are the most important factors that influence the Tujia EFL learning style preferences”. Practically, the results help the Tujia EFL learners understand their own learning style preferences and instructors in making decisions about course design and improving the methods of the Tujia EFL classroom teaching. Methodologically, the successful application of both quantitative and qualitative approach and the use of a multidimensional learning-styles instrument expand the methodology of learning styles research. Index Terms—Tujia EFL learners, learning style preferences, ethnic culture, socialization I. -

Financial Analysis

Hunan Xiangxi Rural Environmental Improvement and Green Development Project (RRP PRC 53050-001) FINANCIAL ANALYSIS A. Introduction 1. Financial analysis was conducted to assess the financial viability and sustainability of the project in accordance with relevant Asian Development Bank (ADB) guidelines.1 The analysis mainly comprises (i) a financial viability assessment of revenue-generating subprojects (Table 1); and (ii) a financial sustainability assessment of (a) the Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefectural Government (XPG, the executing agency); and (b) the Jishou City Government and the county governments of Baojing, Fenghuang, Guzhang, Huayuan, Longshan, Luxi, and Yongshun (the implementing agencies), which are responsible for the operation and maintenance (O&M) of the project, to assess their financial capacities in covering the recurrent costs of the project. 2. The project has three outputs that comprise 17 subprojects, of which 11 are revenue- generating subprojects and 6 are nonrevenue-generating subprojects (Table 1). They will be implemented by the XPG and the implementing agencies. Financial viability analysis was conducted to assess the viability of the 11 revenue-generating subprojects by comparing their financial internal rates of return (FIRRs) and weighted average costs of capital (WACCs). Financial sustainability analyses were conducted to assess if the XPG and the implementing agencies have adequate financial capacities to cover the incremental recurrent costs, including the O&M expenditures required to ensure sustainability of the project. Table 1: List of Subprojects Revenue-/ Nonrevenue- Generating Output Subproject Subproject Output 1: Rural 1.1. Wastewater management system waste and sanitation 1.2. Solid waste management Nonrevenue- management 1.3. Renovation of rural households’ unsanitary toilets to sanitary ones generating facilities and subprojects services improved Output 2: Local- 2.1. -

A Complete Collection of Chinese Institutes and Universities For

Study in China——All China Universities All China Universities 2019.12 Please download WeChat app and follow our official account (scan QR code below or add WeChat ID: A15810086985), to start your application journey. Study in China——All China Universities Anhui 安徽 【www.studyinanhui.com】 1. Anhui University 安徽大学 http://ahu.admissions.cn 2. University of Science and Technology of China 中国科学技术大学 http://ustc.admissions.cn 3. Hefei University of Technology 合肥工业大学 http://hfut.admissions.cn 4. Anhui University of Technology 安徽工业大学 http://ahut.admissions.cn 5. Anhui University of Science and Technology 安徽理工大学 http://aust.admissions.cn 6. Anhui Engineering University 安徽工程大学 http://ahpu.admissions.cn 7. Anhui Agricultural University 安徽农业大学 http://ahau.admissions.cn 8. Anhui Medical University 安徽医科大学 http://ahmu.admissions.cn 9. Bengbu Medical College 蚌埠医学院 http://bbmc.admissions.cn 10. Wannan Medical College 皖南医学院 http://wnmc.admissions.cn 11. Anhui University of Chinese Medicine 安徽中医药大学 http://ahtcm.admissions.cn 12. Anhui Normal University 安徽师范大学 http://ahnu.admissions.cn 13. Fuyang Normal University 阜阳师范大学 http://fynu.admissions.cn 14. Anqing Teachers College 安庆师范大学 http://aqtc.admissions.cn 15. Huaibei Normal University 淮北师范大学 http://chnu.admissions.cn Please download WeChat app and follow our official account (scan QR code below or add WeChat ID: A15810086985), to start your application journey. Study in China——All China Universities 16. Huangshan University 黄山学院 http://hsu.admissions.cn 17. Western Anhui University 皖西学院 http://wxc.admissions.cn 18. Chuzhou University 滁州学院 http://chzu.admissions.cn 19. Anhui University of Finance & Economics 安徽财经大学 http://aufe.admissions.cn 20. Suzhou University 宿州学院 http://ahszu.admissions.cn 21. -

Respiratory Healthcare Resource Allocation in Rural Hospitals in Hunan, China: a Cross-Sectional Survey

11 Original Article Page 1 of 10 Respiratory healthcare resource allocation in rural hospitals in Hunan, China: a cross-sectional survey Juan Jiang1, Ruoxi He1, Huiming Yin2, Shizhong Li3, Yuanyuan Li1, Yali Liu2, Fei Qiu2, Chengping Hu1 1Department of Respiratory Medicine, National Key Clinical Specialty, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, China; 2Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan University of Medicine, Huaihua 418099, China; 3Health Policy and Management Office of Health Commission in Hunan Province, Changsha 410008, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: C Hu; (II) Administrative support: C Hu, H Yin, S Li; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: C Hu, J Jiang; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: J Jiang, R He, Y Li, Y Liu, F Qiu; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: C Hu, J Jiang; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Chengping Hu, MD, PhD. #87 Xiangya Road, Kaifu District, Changsha 410008, China. Email: [email protected]. Background: Rural hospitals in China provide respiratory health services for about 600 million people, but the current situation of respiratory healthcare resource allocation in rural hospitals has never been reported. Methods: In the present study, we designed a survey questionnaire, and collected information from 48 rural hospitals in Hunan Province, focusing on their respiratory medicine specialty (RMS), basic facilities and equipment, clinical staffing and available medical techniques. Results: The results showed that 58.3% of rural hospitals established an independent department of respiratory medicine, 50% provided specialized outpatient service, and 12.5% had an independent respiratory intensive care unit (RICU).