CO2 EMISSIONS from CARS: the Facts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penndot Fact Sheet

FACT SHEET Van/Mini-Van Titling and Registration Procedures PURPOSE This fact sheet explains the titling and registration procedures for van and mini-van type vehicles being titled and registered in Pennsylvania. DEFINITIONS Motor home: A motor vehicle designed or adapted for use as mobile dwelling or office; except a motor vehicle equipped with a truck-camper. Passenger Car: A motor vehicle, except a motorcycle, designed primarily for the transportation of persons and designed for carrying no more than 15 passengers including the driver and primarily used for the transportation of persons. The term includes motor vehicles which are designed with seats that may be readily removed and reinstalled, but does not include such vehicles if used primarily for the transportation of property. Truck: A motor vehicle designed primarily for the transportation of property. The term includes motor vehicles designed with seats that may be readily removed and reinstalled if those vehicles are primarily used for the transportation of property. GENERAL RULE Van and mini-van type vehicles are designed by vehicle manufacturers to be used in a multitude of different ways. Many vans are designed with seats for the transportation of persons much like a normal passenger car or station wagon; however, some are manufactured for use as a motor home, while others are designed simply for the transportation of property. Therefore, the proper type of registration plate depends on how the vehicle is to be primarily used. The following rules should help clarify the proper procedures required to title and register a van/mini-van: To register as a passenger car - The van/mini-van must be designed with seating for no more than 15 passengers including the driver, and used for non-commercial purposes. -

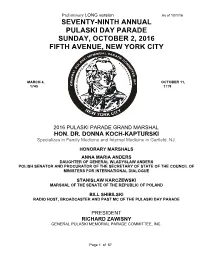

Seventy-Ninth Annual Pulaski Day Parade Sunday, October 2, 2016 Fifth Avenue, New York City

Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 SEVENTY-NINTH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY MARCH 4, OCTOBER 11, 1745 1779 2016 PULASKI PARADE GRAND MARSHAL HON. DR. DONNA KOCH-KAPTURSKI Specializes in Family Medicine and Internal Medicine in Garfield, NJ. HONORARY MARSHALS ANNA MARIA ANDERS DAUGHTER OF GENERAL WLADYSLAW ANDERS POLISH SENATOR AND PROCURATOR OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS FOR INTERNATIONAL DIALOGUE STANISLAW KARCZEWSKI MARSHAL OF THE SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND BILL SHIBILSKI RADIO HOST, BROADCASTER AND PAST MC OF THE PULASKI DAY PARADE PRESIDENT RICHARD ZAWISNY GENERAL PULASKI MEMORIAL PARADE COMMITTEE, INC. Page 1 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 ASSEMBLY STREETS 39A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. M A 38 FLOATS 21-30 38C FLOATS 11-20 38B 38A FLOATS 1 - 10 D I S O N 37 37C 37B 37A A V E 36 36C 36B 36A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. Page 2 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE 79TH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE COMMEMORATING THE SACRIFICE OF OUR HERO, GENERAL CASIMIR PULASKI, FATHER OF THE AMERICAN CAVALRY, IN THE WAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE BEGINS ON FIFTH AVENUE AT 12:30 PM ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016. THIS YEAR WE ARE CELEBRATING “POLISH- AMERICAN YOUTH, IN HONOR OF WORLD YOUTH DAY, KRAKOW, POLAND” IN 2016. THE ‘GREATEST MANIFESTATION OF POLISH PRIDE IN AMERICA’ THE PULASKI PARADE, WILL BE LED BY THE HONORABLE DR. DONNA KOCH- KAPTURSKI, A PROMINENT PHYSICIAN FROM THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY. -

Chrysler 300C Krystal-Coach

CHRYSLER 300C KRYSTAL-COACH Style & allure A hearse can be so nice and stylish... the Chrysler 300C Krystal-Coach. CHRYSLER 300C KRYSTAL-COACH Better off with Marc van Ravensteijn Hearse and Limo Company Funeral mobility is a distinct pro- fession. The funeral sector has completely different require- ments than any other business and personal transport. At Marc van Ravensteijn The Hearse and Limo Company we have gone Exceptional... into the requirements and wishes of funeral organisation in depth, The Chrysler 300C like no other. The result of this is This new hearse version of the Hearse and Limo Company are great attention to design, details Chrysler 300C has a striking their importer for Europe. The and durability. And that translates and stylish profile, which gives hearse based on the Chrysler itself into a carefully put together the vehicle a very fresh and spe- 300C is available with a 3.5 offer of new and used American cial appearance. Krystal-Coach litre V6 petrol engine. But it can hearses, including those made by takes care of the design and also be supplied with perma- Chrysler. American funeral cars building. And that means added nent all-wheel drive (AWD), as are known to be robust, extremely value, as Krystal-Coach builds an option supplied with the 3.5. stylish and timeless. And all of more than 1,500 (!) limousines An exceptional hearse in the this is true for the Chrysler 300C a year in America. This makes funeral sector, meant for fune- Krystal-Coach. You can read all them the most successful buil- ral directors who really want to about it in this flyer. -

Alternative Fuels, Vehicles & Technologies Feasibility

ALTERNATIVE FUELS, VEHICLES & TECHNOLOGIES FEASIBILITY REPORT Prepared by Eastern Pennsylvania Alliance for Clean Transportation (EP-ACT)With Technical Support provided by: Clean Fuels Ohio (CFO); & Pittsburgh Region Clean Cities (PRCC) Table of Contents Analysis Background: .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0: Introduction – Fleet Feasibility Analysis: ............................................................................................... 3 2.0: Fleet Management Goals – Scope of Work & Criteria for Analysis: ...................................................... 4 Priority Review Criteria for Analysis: ........................................................................................................ 4 3.0: Key Performance Indicators – Existing Fleet Analysis ............................................................................ 5 4.0: Alternative Fuel Options – Summary Comparisons & Conclusions: ...................................................... 6 4.1: Detailed Propane Autogas Options Analysis: ......................................................................................... 7 Propane Station Estimate ......................................................................................................................... 8 (Station Capacity: 20,000 GGE/Year) ........................................................................................................ 8 5.0: Key Recommended Actions – Conclusion -

The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy

bailes_hb.qxd 21/3/06 2:14 pm Page 1 Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom) is A special feature of Europe’s Nordic region the Director of SIPRI. She has served in the is that only one of its states has joined both British Diplomatic Service, most recently as the European Union and NATO. Nordic British Ambassador to Finland. She spent countries also share a certain distrust of several periods on detachment outside the B Recent and forthcoming SIPRI books from Oxford University Press A approaches to security that rely too much service, including two academic sabbaticals, A N on force or that may disrupt the logic and I a two-year period with the British Ministry of D SIPRI Yearbook 2005: L liberties of civil society. Impacting on this Defence, and assignments to the European E Armaments, Disarmament and International Security S environment, the EU’s decision in 1999 to S Union and the Western European Union. U THE NORDIC develop its own military capacities for crisis , She has published extensively in international N Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: H management—taken together with other journals on politico-military affairs, European D The Processes and Mechanisms of Control E integration and Central European affairs as E ongoing shifts in Western security agendas Edited by Wuyi Omitoogun and Eboe Hutchful R L and in USA–Europe relations—has created well as on Chinese foreign policy. Her most O I COUNTRIES AND U complex challenges for Nordic policy recent SIPRI publication is The European Europe and Iran: Perspectives on Non-proliferation L S Security Strategy: An Evolutionary History, Edited by Shannon N. -

Future Evolution of Light Commercial Vehicles' Market

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Department of Management and Production Engineering Master of science course in Engineering and Management Master thesis Future evolution of light commercial vehicles’ market Concept definition for 2025 Academic supervisor: Prof. Ing. Marco Cantamessa Company supervisor: Ing. Franco Anzioso Candidate: Valerio Scabbia Academic year 2017/2018 To my parents 2 1 Introduction .......................................................................... 5 2 Methodology and aim of the work ....................................... 6 2.1 Structure……….……………………………………………...…...6 3 Definitions ............................................................................ 7 3.1 Market segments .......................................................................... 7 3.2 Technologies ................................................................................ 9 4 Light commercial vehicles market ..................................... 10 4.1 Definition of LCV ...................................................................... 10 4.2 Customer segmentation .............................................................. 11 4.3 Operating costs .......................................................................... 13 5 Trends… ............................................................................. 14 5.1 Macro Trends ............................................................................. 15 5.2 Regulations ................................................................................ 18 5.3 Sustainability ............................................................................ -

Forced Displacement – Global Trends in 2015

GLObaL LEADER ON StatISTICS ON REfugEES Trends at a Glance 2015 IN REVIEW Global forced displacement has increased in 2015, with record-high numbers. By the end of the year, 65.3 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or human rights violations. This is 5.8 million more than the previous year (59.5 million). MILLION FORCIBLY DISPLACED If these 65.3 million persons 65.3 WORLDWIDE were a nation, they would make up the 21st largest in the world. 21.3 million persons were refugees 16.1 million under UNHCR’s mandate 5.2 million Palestinian refugees registered by UNRWA 40.8 million internally displaced persons1 3.2 million asylum-seekers 12.4 24 86 MILLION PER CENT An estimated 12.4 million people were newly displaced Developing regions hosted 86 per due to conflict or persecution in cent of the world’s refugees under 2015. This included 8.6 million UNHCR’s mandate. At 13.9 million individuals displaced2 within people, this was the highest the borders of their own country figure in more than two decades. and 1.8 million newly displaced The Least Developed Countries refugees.3 The others were new provided asylum to 4.2 million applicants for asylum. refugees or about 26 per cent of the global total. 3.7 PERSONS MILLION EVERY MINUTE 183/1000 UNHCR estimates that REFUGEES / at least 10 million people On average 24 people INHABITANTS globally were stateless at the worldwide were displaced from end of 2015. However, data their homes every minute of Lebanon hosted the largest recorded by governments and every day during 2015 – some number of refugees in relation communicated to UNHCR were 34,000 people per day. -

Funeral Transport Collection Funeral Transport Collection

Funeral Transport Collection Funeral Transport Collection The final journey can be an emotional and poignant part of the service and often families look to personalise this by selecting a vehicle to reflect the life and passions of their loved one. From a traditional hearse, a majestic horse drawn carriage through to a motorcycle, we have a wide range of transport options available to help you create a unique and fitting tribute. OrderHorse ofDrawn service Hearse A cortège led by a horse drawn hearse creates an air of opulence, along with traditional style and elegance. We can provide a selection of black or white horses with a beautiful glass-sided hearse. Mourning coaches are also available and come in a choice of black or white. Black Glass-Sided Hearse Pair of horses £1120 Pair of horses with an outrider £1435 Team of horses (4) £1695 Pick-axe of horses (5) £2115 OrderHorse ofDrawn service Hearse White Glass-Sided Hearse Pair of horses £1120 Pair of horses with an outrider £1540 Team of horses (4) £1800 Black Mourning Coach White Mourning Coach £945 £995 OrderVintage of Lorry service Hearse 1950 Leyland Beaver £1,590 The vintage lorry hearse is a distinctive and fitting tribute if you are looking to add an individual touch to your loved one’s final journey. This beautiful red and blue 1950 Leyland Beaver is a colourful option with a special plinth on the back for the coffin and flower tributes. OrderVintage of Lorry service Hearse 1929 Guy Lorry £1,530 The classic 1929 Guy Lorry provides a unique and dignified means of transportation for your loved one on their special journey. -

The European Union V. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests As a Party to the International Criminal Court, 27 Hastings Int'l & Comp

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 27 Article 5 Number 1 Fall 2003 1-1-2003 The urE opean Union v. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests as a Party to the International Criminal Court Barbi Appelquist Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Barbi Appelquist, The European Union v. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests as a Party to the International Criminal Court, 27 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 77 (2003). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol27/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The European Union v. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests as a Party to the International Criminal Court By BARBI APPELQUIST* Introduction Estonia, the United States and all current members of the European Union have signed the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights.' This body of public international law protects the following human rights of alleged criminals: "the protection against arbitrary arrest, detention, or invasions of privacy; a presumption of innocence; and a promise of 'full equality' at a fair, public trial, before a neutral arbiter, with 'all the guarantees necessary' for the defense."2 The International Criminal Court (ICC) was created to provide a fair trial for those accused of certain particularly serious crimes in an objective international setting.3 Estonia became a party to the ICC when its President signed the * J.D. -

Beyond the State of the Art of Electric Vehicles: a Fact-Based Paper of the Current and Prospective Electric Vehicle Technologies

Review Beyond the State of the Art of Electric Vehicles: A Fact-Based Paper of the Current and Prospective Electric Vehicle Technologies Joeri Van Mierlo 1,2,* , Maitane Berecibar 1,2 , Mohamed El Baghdadi 1,2 , Cedric De Cauwer 1,2 , Maarten Messagie 1,2 , Thierry Coosemans 1,2 , Valéry Ann Jacobs 1 and Omar Hegazy 1,2 1 Mobility, Logistics and Automotive Technology Research Centre (MOBI), Department of Electrical Engineering and Energy Technology (ETEC), Faculty of Engineering, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), 1050 Brussel, Belgium; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.E.B.); [email protected] (C.D.C.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (V.A.J.); [email protected] (O.H.) 2 Flanders Make, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Today, there are many recent developments that focus on improving the electric vehicles and their components, particularly regarding advances in batteries, energy management systems, autonomous features and charging infrastructure. This plays an important role in developing next electric vehicle generations, and encourages more efficient and sustainable eco-system. This paper not only provides insights in the latest knowledge and developments of electric vehicles (EVs), but also the new promising and novel EV technologies based on scientific facts and figures—which could be from a technological point of view feasible by 2030. In this paper, potential design and modelling tools, such as digital twin with connected Internet-of-Things (IoT), are addressed. Furthermore, Citation: Van Mierlo, J.; Berecibar, the potential technological challenges and research gaps in all EV aspects from hard-core battery M.; El Baghdadi, M.; De Cauwer, C.; Messagie, M.; Coosemans, T.; Jacobs, material sciences, power electronics and powertrain engineering up to environmental assessments V.A.; Hegazy, O. -

Driving Resistances of Light-Duty Vehicles in Europe

WHITE PAPER DECEMBER 2016 DRIVING RESISTANCES OF LIGHT- DUTY VEHICLES IN EUROPE: PRESENT SITUATION, TRENDS, AND SCENARIOS FOR 2025 Jörg Kühlwein www.theicct.org [email protected] BEIJING | BERLIN | BRUSSELS | SAN FRANCISCO | WASHINGTON International Council on Clean Transportation Europe Neue Promenade 6, 10178 Berlin +49 (30) 847129-102 [email protected] | www.theicct.org | @TheICCT © 2016 International Council on Clean Transportation TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary ...................................................................................................................II Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... IV 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Physical principles of the driving resistances ....................................................................... 2 1.2 Coastdown runs – differences between EU and U.S. ........................................................ 5 1.3 Sensitivities of driving resistance variations on CO2 emissions ..................................... 6 1.4 Vehicle segments ............................................................................................................................. 8 2. Evaluated data sets ..............................................................................................................9 2.1 ICCT internal database ................................................................................................................. -

Truck Vs. Van Report

Truck vs. Van Report This report is the culmination of research and information pulled from many sources, including OEM resources, fleet data, and various articles. The subject of the report is pickup trucks vs. work vans for fleet solutions and examining the value of each. COST SAVINGS Below is a breakdown of the available cost savings when considering pickup trucks rather than work vans. To show a distinct comparison between trucks and vans under the same manufacturer, these graphs examine cost savings, especially Cost Per Mile. Data provided by www.fleet-central.com Capital Investment Fuel Savings Maintenance Acquisition costs: Fuel cost for 60k miles: Maintenance costs: Full size pickup trucks $18,860 Full size pickup trucks $11,633 Full size pickup trucks $1,894 Full size vans $24,124 Full size vans $12,807 Full size vans $2,299 $30,000 $13,000 $2,500 $12,800 $25,000 $12,600 $2,000 $20,000 $12,400 $12,200 $1,500 $15,000 $12,000 $11,800 $1,000 $10,000 $11,600 $500 $5,000 $11,400 $11,200 $0 $11,000 $0 Trucks Vans Trucks Vans Trucks Vans Depreciation Resale Value Cost per Mile Actual depreciation: Fuel cost for 60K miles: Average cost per mile: Full size pickup trucks $8,885 Full size pickup trucks $9,975 Full size pickup trucks $0.37 Full size vans $14,979 Full size vans $9,172 Full size vans $0.50 $16,000 $10,200 $0.60 $14,000 $10,000 $0.50 $12,000 $9,800 $0.40 $10,000 $9,600 $8,000 $9,400 $0.30 $6,000 $9,200 $0.20 $4,000 $9,000 $0.10 $2,000 $8,800 $0 $8,600 $0.00 Trucks Vans Trucks Vans Trucks Vans CAPABILITIES Not only is there monetary value in choosing trucks over vans, there are capability advantages as well.