AFRICA: Mapping Islamic Militancy – Past, Present and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Al Qaeda Operatives Took Part in Benghazi Attack

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com OUice of the Director of National [ntel1igence Washington, DC 20511 John Greenewald, Jr. DEC 0 8 2015 Re: ODNI FOIA Case DF-2013-00205 Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your email to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) on 15 September 2013, in which you requested an appeal of your FOIA case DF-2013-00190 regarding information about the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya. During subsequent communication with our FOIA office, you agreed to withdraw your appeal and allow us to process the case as a new request (Enclosure 1). Your request was processed in accordance with the FOIA, 5 U.S.C. 552, as amended, and material was located that is responsive to your request (Enclosure 2). Upon review, certain information has been determined to be currently and properly classified in accordance with Executive Order 13526, Section 1.4(c), and that is, therefore, exempt from disclosure pursuant to FOIA exemption (b)(1). In addition, information has been withheld pursuant to the following FOIA exemptions: • (b)(3), which applies to information exempt by statute, specifically 50 U.S.C. § 3024(i), which protects intelligence sources and methods from unauthorized disclosure; and • (b)(3), the relevant withholding statute is the National Security Act of 1947, as amended, 50 U.S.C. -

The Renewed Threat of Terrorism to Turkey

JUNE 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 6 Contents The Renewed Threat of FEATURE ARTICLE 1 The Renewed Threat of Terrorism Terrorism to Turkey to Turkey By Stephen Starr By Stephen Starr REPORTS 4 The Local Face of Jihadism in Northern Mali By Andrew Lebovich 10 Boko Haram’s Evolving Tactics and Alliances in Nigeria By Jacob Zenn 16 A Profile of Khan Said: Waliur Rahman’s Successor in the Pakistani Taliban By Daud Khattak 19 Tweeting for the Caliphate: Twitter as the New Frontier for Jihadist Propaganda By Nico Prucha and Ali Fisher 23 Rebellion, Development and Security in Pakistan’s Tribal Areas By Hassan Abbas and Shehzad H. Qazi 26 Peace with the FARC: Integrating Drug-Fueled Guerrillas into Alternative Development Programs? By Jorrit Kamminga People of Reyhanli chant slogans as riot police block them during the funerals of the victims of the May 11 car bombs. - STR/AFP/Getty or three decades, Turkey’s court-enforced blackout, but Turkish terrorist threat has been viewed authorities arrested nine Turkish 29 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity largely through the lens of men—believed to be linked to Syrian 32 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts Kurdish militancy. Yet just as intelligence groups—for their role in the Fone front closes down,1 a new hazard 4 attacks. has emerged, primarily as a result of the current war in Syria. On May 11, 2013, Mihrac Ural, an Alawite Turk from Hatay Turkey suffered the deadliest terrorist Province who has been an important pro- About the CTC Sentinel attack in its modern history when 52 Damascus militia figure in the conflict in The Combating Terrorism Center is an people were killed in twin car bombings Syria, has been widely blamed for the independent educational and research in Reyhanli, a town in Hatay Province bombings. -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

U.S. Counterterrorism Priorities and Challenges in Africa”

Statement of Alexis Arieff Specialist in African Affairs Before Committee on Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on National Security U.S. House of Representatives Hearing on “U.S. Counterterrorism Priorities and Challenges in Africa” December 16, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov TE10044 Congressional Research Service 1 hairman Lynch, Ranking Member Hice, and Members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for inviting the Congressional Research Service to testify today. As requested, I will focus particular attention on current trends in West Africa’s Sahel region, which is within my C area of specialization at CRS, along with U.S. responses and considerations for congressional oversight. My testimony draws on the input of CRS colleagues who cover other parts of the continent and related issues. Introduction Islamist armed groups have proliferated and expanded their geographic presence in sub-Saharan Africa (“Africa,” unless noted) over the past decade.1 These groups employ terrorist tactics, and several have pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda or the Islamic State (IS, aka ISIS or ISIL) and operate across borders. Most, however, also operate as local insurgent movements that seek to attack and undermine state presence and control. Conflicts involving these groups have caused the displacement of millions of people in Africa and deepened existing development and security challenges. Local civilians and security forces have endured the overwhelming brunt of fatalities, as well as the devastating humanitarian impacts. Somalia, the Lake Chad Basin, and West Africa’s Sahel region have been most affected (Figure 1).2 The Islamic State also has claimed attacks as far afield as eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and northern Mozambique over the past year.3 The extent to which Islamist armed groups in Africa pose a threat to U.S. -

Algeria's Underused Potential in Security Cooperation in the Sahel

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT POLICY BRIEFING Algeria’s underused potential in security cooperation in the Sahel region Abstract Algeria is a regional power in both economic, political and military terms. Up to now, relations between the EU and Algeria have been mainly based on economic considerations. The crisis in Mali, the Franco-African military intervention (AFISMA) and the terrorist attacks at the gas facility In Amenas in eastern Algeria have opened a new window of opportunity for reinforced cooperation in the field of security between Algeria and the EU in order to combat common threats. Given its strong military power and political stature in the region, Algeria has the potential to develop into an important ally of the EU in the Sahel region. The probable transfer of presidential powers in Algeria will offer a chance for Algeria to reshape its policy in the region, as an assertive and constructive regional power not only in the Maghreb but also in West Africa. DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2013_71 June 2013 PE 491.510 EN Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This Policy Briefing is an initiative of the Policy Department, DG EXPO. AUTHORS: Martina LAGATTA, Ulrich KAROCK, Manuel MANRIQUE and Pekka HAKALA Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union Policy Department WIB 06 M 71 rue Wiertz 60 B-1047 Brussels Feedback to [email protected] is welcome. Editorial Assistant: Agnieszka PUNZET LINGUISTIC VERSIONS: Original: EN ABOUT THE PUBLISHER: Manuscript completed on 24 June 2013. © European Union, 2013 Printed inBelgium This Policy Briefing is available on the intranet site of the Directorate-General for External Policies, in the Regions and countries or Policy Areas section. -

Deadly Attack on a Gold Mining City, Burkina Faso 10 June 2021 Sentinel-1 CSAR IW Acquired on 08 April 2015 at 18:11:17 UTC

Sentinel Vision EVT-883 Deadly attack on a gold mining city, Burkina Faso 10 June 2021 Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 08 April 2015 at 18:11:17 UTC ... Se ntinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 30 May 2021 from 18:11:21 to 18:12:11 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 31 May 2021 at 10:15:59 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 05 June 2021 at 10:20:21 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Security, natural ressources, mine, climate change, Burkina Faso Fig. 1 - S2 (31.05.2021) - On 5 June 2021, the village of Solhan in Burkina Faso was again attacked by armed assailants. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (31.05.2021) - At least 174 people have been killed in this mining community located near the border with Niger. 2D view Burkina Faso mourns after at least attackers killed 174 people in the village of Solhan. Elian Peltier of the New-York Times reports: "Armed assailants killed more than 100 people in an attack on a village in northern Burkina Faso, the government said on Saturday, burning houses and leaving many more injured in one of the deadliest assaults the West African nation has seen in years." Fig. 3 - S2 (02.05.2016) - The rise of artisanal mining (circles) between 2016 & 2021 led the city (rectangle) to grow quickly. 2D animation 2D view "The attackers struck early Saturday [5 June] morning, first at a gold mine near the village of Sobha, near the border with Niger, according to Rida Lyammouri, a Washington-based expert, before then going after civilians." Radio France International details: "The attackers also set fire to vehicles and shops after looting everything they could. -

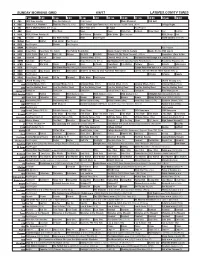

Sunday Morning Grid 6/4/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/4/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Mom/Memorial PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2017 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å College Rugby 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Rock-Park Outback Chew: Best Paid IndyCar 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program North Country ››› (R) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Smart Fats Easy Yoga: The Secret The Path to Wealth-May Always Hungry? With Dr. Ludwig Maybe It’s You With Lauren 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Motown 25 (My Music Presents) (TVG) Å Carpenters: Close to You 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Sor Tequila (1977, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program The Storm Warriors ›› (2009) Aaron Kwok. -

Al-Qaïda», Taliban: Verordnung Vom 2

Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research EAER State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO Bilateral Economic Relations Sanctions Version of 13.04.2019 Sanctions program: «Al-Qaïda», Taliban: Verordnung vom 2. Oktober 2000 über Massnahmen gegenüber Personen und Organisationen mit Verbindungen zu Usama bin Laden, der Gruppierung «Al-Qaïda» oder den Taliban (SR 946.203), Anhang 2 Origin: UN Sanctions: Art. 3 Abs. 1 und 2 (Finanzsanktionen) und Art. 4 sowie 4a (Ein- und Durchreiseverbot) Sanctions program: «Al-Qaïda», Taliban: Ordonnance du 2 octobre 2000 des mesures à l’encontre de personnes et entités liées à Oussama ben Laden, au groupe «Al-Qaïda» ou aux Taliban (RS 946.203), annexe 2 Origin: UN Sanctions: art. 3, al. 1 et 2 (Sanctions financières) et art. 4 et 4a (Interdiction de séjour et de transit) Sanctions program: «Al-Qaïda», Taliban: Ordinanza del 2 ottobre 2000 che istituisce provvedimenti nei confronti delle persone e delle organizzazioni legate a Osama bin Laden, al gruppo «Al-Qaïda» o ai Taliban (RS 946.203), allegato 2 Origin: UN Sanctions: art. 3 cpv. 1 e 2 (Sanzioni finanziarie) e art. 4 e 4a (Divieto di entrata e di transito) Individuals SSID: 10-13501 Foreign identifier: QI.A.12.01. Name: Nashwan Abd Al-Razzaq Abd Al- Baqi DOB: 1961 POB: Mosul, Iraq Good quality a.k.a.: a) Abdal Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi b) Abd Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi c) Omar Uthman Mohammed d) Abdul Hadi Arif Ali Low quality a.k.a.: a) Abu Abdallah b) Abdul Hadi al-Taweel c) Abd al-Hadi al-Ansari d) Abd al-Muhayman e) Abu Ayub Nationality: Iraq Identification document: Other No. -

GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 3950

GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 3950 GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com TERRORIST ATTACKS AND THE INFLUENCE OF ILLICIT OR HARD DRUGS: IMPLICATIONS TO BORDER SECURITY IN WEST AFRICA Dr. Temitope Francis Abiodun Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria [email protected] +2348033843918 Gbadamosi Musa M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Damilola Adeyinka M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Anthony Ifeanyichukwu Ndubuisi M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Joshua Akande M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Omoyele Ayomikun Adeniran M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Adesina Mukaila Funso M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Chiamaka Ugbor Precious M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Abayomi Olawale Quadri M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria GSJ© 2020 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 3951 ABSTRACT The West African sub-region has experienced a devastating surge in terrorist attacks against civilian and military targets for over one and half decades now. And this has remained one of the main obstacles to sustenance of peaceful co-existence in the region. This is evident in the myriads of terrorist attacks from the various terrorist and insurgent groups across West African borders: Boko Haram, ISWAP (Islamic State West African Province), Al-Barakat, Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa. -

The Trans Sahara Counter Terrorism Partnership Building Partner Capacity to Counter Terrorism and Violent Extremism

The Trans Sahara Counter Terrorism Partnership Building Partner Capacity to Counter Terrorism and Violent Extremism Lesley Anne Warner Cleared for public release CRM-2014-U-007203-Final March 2014 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “problem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Re-Conceptualizing Orders in the Mena Region the Analytical Framework of the Menara Project

No. 1, November 2016 METHODOLOGY AND CONCEPT PAPERS RE-CONCEPTUALIZING ORDERS IN THE MENA REGION THE ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE MENARA PROJECT Edited by Eduard Soler i Lecha (coordinator), Silvia Colombo, Lorenzo Kamel and Jordi Quero This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement No 693244 Middle East and North Africa Regional Architecture: Mapping Geopolitical Shifts, Regional Order and Domestic Transformations METHODOLOGY AND CONCEPT PAPERS No. 1, November 2016 RE-CONCEPTUALIZING ORDERS IN THE MENA REGION THE ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE MENARA PROJECT Edited by Eduard Soler i Lecha (coordinator), Silvia Colombo, Lorenzo Kamel and Jordi Quero ABSTRACT The aim of this work is to set the conceptual architecture for the MENARA Project. It is articulated in five thematic sections. The first one traces back the major historical junctures in which key powers shaped the defining features of the present-day MENA region. Section 2 sets the geographical scope of the project, maps the distribution of power and defines regional order and its main features. Section 3 focuses on the domestic orders in a changing region by gauging and tracing the evolution of four trends, namely the erosion of state capacity; the securitization of regime policies; the militarization of contention; and the pluralization of collective identities. Section 4 links developments in the global order to their impact on the region in terms of power, ideas, norms and identities. The last section focuses on foresight studies and proposes a methodology to project trends and build scenarios. All sections, as well as the conclusion, formulate specific research questions that should help us understand the emerging geopolitical order in the MENA. -

The Derna Mujahideen Shura Council: a Revolutionary Islamist Coalition in Libya by Kevin Truitte

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 5 The Derna Mujahideen Shura Council: A Revolutionary Islamist Coalition in Libya by Kevin Truitte Abstract The Derna Mujahideen Shura Council (DMSC) – later renamed the Derna Protection Force – was a coalition of Libyan revolutionary Islamist groups in the city of Derna in eastern Libya. Founded in a city with a long history of hardline Salafism and ties to the global jihadist movement, the DMSC represented an amalgamation of local conservative Islamism and revolutionary fervor after the 2011 Libyan Revolution. This article examines the group’s significant links to both other Libyan Islamists and to al-Qaeda, but also its ideology and activities to provide local security and advocacy of conservative governance in Derna and across Libya. This article further details how the DMSC warred with the more extremist Islamic State in Derna and with the anti-Islamist Libyan National Army, defeating the former in 2016 but ultimately being defeated by the latter in mid-2018. The DMSC exemplifies the complex local intersection between revolution, Islamist ideology, and jihadism in contemporary Libya. Keywords: Libya, Derna, Derna Mujahideen Shura Council, al-Qaeda, Islamic State Introduction The city of Derna has, for more than three decades, been a center of hardline Islamist jihadist dissent in eastern Libya. During the rule of Libya’s strongman Muammar Qaddafi, the city hosted members of the al-Qaeda- linked Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) and subsequently served as their stronghold after reconciliation with the Qaddafi regime. The city sent dozens of jihadists to fight against the United States in Iraq during the 2000s.