The Inside Story: an Arts-Based Exploration of the Creative Process of the Storyteller As Leader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pet Shop Boys Introspective (Introspectivo) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pet Shop Boys Introspective (Introspectivo) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Introspective (Introspectivo) Country: Ecuador Released: 1988 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1773 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1773 mb WMA version RAR size: 1819 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 443 Other Formats: MP3 MMF ASF ADX AHX AC3 VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Hago Lo Que Se Me Antoja (Left To My Own Devices) A1 Producer – Stephen Lipson, Trevor HornVocals – Sally Bradshaw Quiero Un Perro (I Want A Dog) A2 Mixed By – Frankie Knuckles La Danza Del Dominó (Domino Dancing) A3 Mixed By – Lewis A. Martineé, Mike Couzzi, Rique AlonsoProducer – Lewis A. Martineé No Tengo Miedo (I'm Not Scared) B1 Producer – David Jacob (Siempre En Mi Mente / En Mi Casa) (Always On My Mind / In My House) B2 Producer – Julian MendelsohnWritten-By – Christopher*, James*, Thompson* Está Bien (It's Alright) B3 Producer – Stephen Lipson, Trevor HornWritten-By – Sterling Void Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Ifesa Distributed By – Fonorama Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year PCS 7325, 79 Pet Shop Introspective (LP, Parlophone, PCS 7325, 79 UK 1988 0868 1 Boys Album) Parlophone 0868 1 Pet Shop Introspectivo (Cass, 66312 EMI 66312 Argentina 1988 Boys Album, RE) Pet Shop Introspectivo (Cass, 20059 EMI 20059 Argentina 1988 Boys Album) 080 79 0868 Parlophone, 080 79 0868 Pet Shop Introspective (LP, 1, 080 7 EMI, 1, 080 7 Spain Unknown Boys Album) 90868 1 Parlophone, EMI 90868 1 Introspective (CD, Pet Shop Not On Label 13421 Album, -

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

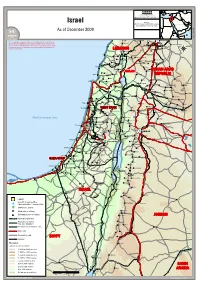

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Flowers for Algernon.Pdf

SHORT STORY FFlowerslowers fforor AAlgernonlgernon by Daniel Keyes When is knowledge power? When is ignorance bliss? QuickWrite Why might a person hesitate to tell a friend something upsetting? Write down your thoughts. 52 Unit 1 • Collection 1 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand subplots and Reader/Writer parallel episodes. Reading Skills Track story events. Notebook Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Subplots and Parallel Episodes A long short story, like the misled (mihs LEHD) v.: fooled; led to believe one that follows, sometimes has a complex plot, a plot that con- something wrong. Joe and Frank misled sists of intertwined stories. A complex plot may include Charlie into believing they were his friends. • subplots—less important plots that are part of the larger story regression (rih GREHSH uhn) n.: return to an earlier or less advanced condition. • parallel episodes—deliberately repeated plot events After its regression, the mouse could no As you read “Flowers for Algernon,” watch for new settings, charac- longer fi nd its way through a maze. ters, or confl icts that are introduced into the story. These may sig- obscure (uhb SKYOOR) v.: hide. He wanted nal that a subplot is beginning. To identify parallel episodes, take to obscure the fact that he was losing his note of similar situations or events that occur in the story. intelligence. Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described deterioration (dih tihr ee uh RAY shuhn) on page 55 as you read this story. n. used as an adj: worsening; declining. Charlie could predict mental deterioration syndromes by using his formula. -

TAU Archaeology the Jacob M

TAU Archaeology The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities | Tel Aviv University Number 4 | Summer 2018 Golden Jubilee Edition 1968–2018 TAU Archaeology Newsletter of The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities Number 4 | Summer 2018 Editor: Alexandra Wrathall Graphics: Noa Evron Board: Oded Lipschits Ran Barkai Ido Koch Nirit Kedem Contact the editors and editorial board: [email protected] Discover more: Institute: archaeology.tau.ac.il Department: archaeo.tau.ac.il Cover Image: Professor Yohanan Aharoni teaching Tel Aviv University students in the field, during the 1969 season of the Tel Beer-sheba Expedition. (Courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University). Photo retouched by Sasha Flit and Yonatan Kedem. ISSN: 2521-0971 | EISSN: 252-098X Contents Message from the Chair of the Department and the Director of the Institute 2 Fieldwork 3 Tel Shimron, 2017 | Megan Sauter, Daniel M. Master, and Mario A.S. Martin 4 Excavation on the Western Slopes of the City of David (‘Giv’ati’), 2018 | Yuval Gadot and Yiftah Shalev 5 Exploring the Medieval Landscape of Khirbet Beit Mamzil, Jerusalem, 2018 | Omer Ze'evi, Yelena Elgart-Sharon, and Yuval Gadot 6 Central Timna Valley Excavations, 2018 | Erez Ben-Yosef and Benjamin -

OBITUARIES Picked up at a Comer in New York City

SUMMER 2004 - THE AVI NEWSLETTER OBITUARIES picked up at a comer in New York City. gev until his jeep was blown up on a land He was then taken to a camp in upper New mine and his injuries forced him to return York State for training. home one week before the final truce. He returned with a personal letter nom Lou After the training, he sailed to Harris to Teddy Kollek commending him Marseilles and was put into a DP camp on his service. and told to pretend to be mute-since he spoke no language other than English. Back in Brooklyn Al worked While there he helped equip the Italian several jobs until he decided to move to fishing boat that was to take them to Is- Texas in 1953. Before going there he took rael. They left in the dead of night from Le time for a vacation in Miami Beach. This Havre with 150 DPs and a small crew. The latter decision was to determine the rest of passengers were carried on shelves, just his life. It was in Miami Beach that he met as we many years later saw reproduced in his wife--to-be, Betty. After a whirlwind the Museum of Clandestine Immigration courtship they were married and decided in Haifa. Al was the cook. On the way out to raise their family in Miami. He went the boat hit something that caused a hole into the uniform rental business, eventu- Al Wank, in the ship which necessitated bailing wa- ally owning his own business, BonMark Israel Navy and Palmach ter the entire trip. -

ISRAEL 15 Study Visit What Will It Take to Leap Israel's Social and Economic Performance? Mon-Thu, June 8 – June 11, 2009

1 March 2009 ISRAEL 15 Study Visit What Will It Take to Leap Israel's Social and Economic Performance? Mon-Thu, June 8 – June 11, 2009 The ISRAEL 15 Vision The ISRAEL 15 Vision aims to place Israel among the fifteen leading countries in terms of quality of life. This vision requires a 'leapfrog' from our present state of development i.e. a significant and continuous improvement in Israel's social and economic performance in comparison to other countries. Our Study Visit will focus on this vision and challenge. The ISRAEL 15 Agenda and Strategy There is no recipe for leapfrogging; it is the result of a virtuous alignment in economic policy, powerful global trends and national leadership. Few countries have leapt including Ireland, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Chile, and Israel (between the 50s- 70s). The common denominator among these countries has been their agenda. They focused on: developing a rich and textured vision; exhausting engines of growth; tapping into unique advantages; improving the capacity for taking decisions and implementing them; benchmarking with other countries; and turning development and growth into a national obsession. Furthermore, leapfrogging requires a top-down process driven by the government, as well as a bottom-up mobilization of the key sectors of society such as mayors and municipal governments, business leaders, nonprofits, philanthropists, career public servants and, in Israel's case, also the world Jewry. The Study Visit will explore this agenda as it applies to Israel. The Second ISRAEL 15 Conference; Monday, June 8, 2009 The Second ISRAEL 15 Conference titled: "Effectuating the Vision Now!" will be held on Monday, June 8th. -

Israel Resource Cards (Digital Use)

WESTERN WALL ַה ּכֹו ֶתל ַה ַּמ ַעָר ִבי The Western Wall, known as the Kotel, is revered as the holiest site for the Jewish people. A part of the outer retaining wall of the Second Temple that was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE, it is the place closest to the ancient Holy of Holies, where only the Kohanim— —Jewish priests were allowed access. When Israel gained independence in 1948, Jordan controlled the Western Wall and all of the Old City of Jerusalem; the city was reunified in the 1967 Six-Day War. The Western Wall is considered an Orthodox synagogue by Israeli authorities, with separate prayer spaces for men and women. A mixed egalitarian prayer area operates along a nearby section of the Temple’s retaining wall, raising to the forefront contemporary ideas of religious expression—a prime example of how Israel navigates between past and present. SITES AND INSIGHTS theicenter.org SHUK ׁשוּק Every Israeli city has an open-air market, or shuk, where vendors sell everything from fresh fruits and vegetables to clothing, appliances, and souvenirs. There’s no other place that feels more authentically Israeli than a shuk on Friday afternoon, as seemingly everyone shops for Shabbat. Drawn by the freshness and variety of produce, Israelis and tourists alike flock to the shuk, turning it into a microcosm of the country. Shuks in smaller cities and towns operate just one day per week, while larger markets often play a key role in the city’s cultural life. At night, after the vendors go home, Machaneh Yehuda— —Jerusalem’s shuk, turns into the city’s nightlife hub. -

I Began My Research by Visiting Several Important Historical Sites in Israel. These Sites Include Former Prime Minister Ben Guri

I began my research by visiting several important historical sites in Israel. These sites include former Prime Minister Ben Gurion’s home, Independence Hall, the Palmach Museum, the Ayalon Institute, Caesarea, Akko, Gamla, Tzafat, Masada, Yad Veshem, the Ramparts Walk, the Temple Mount, and the Israel Museum. First, I visited the home of the first Prime Minister of Israel, Ben Gurion, to learn the significant impact this man had in helping to create the State of Israel. He pushed for Israel to declare independence in 1948 in Independence Hall, which I also visited. Ben Gurion had a vision to create a modern Hebrew city where people only speak Hebrew. When the UN voted to adopt the state of Israel on November 29, 1947, Ben Gurion and other leaders formally declared Israel’s independence on May 14, 1948, in Independence Hall. I also visited the very spot in Independence Hall where Ben Gurion announced to all Israelis that Israel declared independence. On this date, Hatikvah was sung as Israel’s national anthem for the first time. I also visited the Palmach Museum in Tel Aviv to learn more about Israel’s road to independence and the history of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). The IDF play a large role in both Israeli culture and politics today, as there is mandatory service for all 18-year-olds. In this museum, I learned about the background of the Palmach fighting group, such as how this group originally began in 1941, was originally called the Haganah, and changed to the Palmach after they were trained by the British to fight the Nazi’s. -

Scouting Palestinian Territory, 1940- 1948

Scouting In the years between 1943 and1948, squads of young scouts from the Haganah, the pre- Palestinian state armed organization and forerunner of Territory, 1940- the Israel Defense Forces, were employed to gather intelligence about Palestinian villages 1948: and urban neighborhoods1 in preparation for Haganah Village a future conflict and occupation, and as part of a more general project of creating files on Files, Aerial Photos, target sites.2 and Surveys The information was usually collected Rona Sela under the guise of nature lessons aimed at getting to know the country, or of hikes that were common in that period. The scouts systematically built up a database of geographical, topographical and planning information about the villages and population centers. This included detailed descriptions of roads, neighborhoods, houses, public buildings, objects, wells, Palmach Squadron, Al-Majdal (Gaza District), caves, wadis, and so forth. 1947, Aerial Photograph, Haganah Archive. Overall, this intelligence effort was [ 38 ] Scouting Palestinian Territory, 1940-1948: Haganah Village Files, Aerial Photos, and Surveys known as the “Village Files” project, reflecting the fact that most of the sites about which information was collected were the numerous Palestinian villages existing in Palestine before 1948, and that documenting those villages was a central mission. The scouts’ work included perspective sketches, maps, drawings and photographs of each village and its surroundings. The maps used by the scouts were collected in a secret base on Mapu Street in Tel Aviv, located in a cellar that was given the cover name of “the engineering office” and code-named “the roof.” Detailed information about the villages was meticulously catalogued and organized in files by the planning bureau of the Haganah general staff, then held in the organization’s territorial command centers around the country. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Iran, Terrorism, and Weapons of Mass Destruction

Iran, Terrorism, and Weapons of Mass Destruction Prepared Remarks for the hearing entitled “WMD Terrorism and Proliferant States” before the Subcommittee on the Prevention of Nuclear and Biological Attacks of the Homeland Security Committee September 8, 2005 Dr. Daniel Byman Director, Center for Peace and Security Studies, Georgetown University Senior Fellow, Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution E-mail: [email protected] Iran, Terrorism, and Weapons of Mass Destruction Chairman Linder, Members of the Committee, and Committee staff, I am grateful for this opportunity to speak before you today. I am speaking today as a Professor in the Georgetown University Security Studies Program and as a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings’ Saban Center for Middle East Policy. My remarks are solely my own opinion: they do not reflect my past work for the intelligence community, the 9/11 Commission, the U.S. Congress, or other branches of the U.S. government. Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iran has been one of the world’s most active sponsors of terrorism. Tehran has armed, trained, financed, inspired, organized, and otherwise supported dozens of violent groups over the years. Iran has backed not only groups in its Persian Gulf neighborhood, but also terrorists and radicals in Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Bosnia, the Philippines, and elsewhere.1 This support remains strong even today. It comes as no surprise then, twenty five years after the revolution, the U.S. State Department still considers Iran “the most active state sponsor of terrorism.”2 Yet despite Iran’s very real support for terrorism today, I contend that it is not likely to transfer chemical, biological, nuclear, or radiological weapons to terrorists for three major reasons. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers.