UNIVERSITIES and PUBLIC POLICY Transcript of a Presentation By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 The Honorable Sally Yates Acting Attorney General Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530 The Honorable Thomas A. Shannon Acting Secretary Department of State 2201 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20520 Secretary Kelly, Acting Attorney General Yates, Acting Secretary Shannon: As former cabinet Secretaries, senior government officials, diplomats, military service members and intelligence community professionals who have served in the Bush and Obama administrations, we, the undersigned, have worked for many years to make America strong and our homeland secure. Therefore, we are writing to you to express our deep concern with President Trump’s recent Executive Order directed at the immigration system, refugees and visitors to this country. This Order not only jeopardizes tens of thousands of lives, it has caused a crisis right here in America and will do long-term damage to our national security. In the middle of the night, just as we were beginning our nation’s commemoration of the Holocaust, dozens of refugees onboard flights to the United States and thousands of visitors were swept up in an Order of unprecedented scope, apparently with little to no oversight or input from national security professionals. Individuals, who have passed through multiple rounds of robust security vetting, including just before their departure, were detained, some reportedly without access to lawyers, right here in U.S. airports. They include not only women and children whose lives have been upended by actual radical terrorists, but brave individuals who put their own lives on the line and worked side-by-side with our men and women in uniform in Iraq now fighting against ISIL. -

Process Makes Perfect Best Practices in the Art of National Security Policymaking

AP PHOTO/CHARLES DHARAPAK PHOTO/CHARLES AP Process Makes Perfect Best Practices in the Art of National Security Policymaking By Kori Schake, Hoover Institution, and William F. Wechsler, Center for American Progress January 2017 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Process Makes Perfect Best Practices in the Art of National Security Policymaking By Kori Schake, Hoover Institution, and William F. Wechsler, Center for American Progress January 2017 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 6 Findings 14 First-order questions for the next president 17 Best practices to consider 26 Policymaking versus oversight versus crisis management 36 Meetings, meetings, and more meetings 61 Internal NSC staff management 72 Appendix A 73 About the authors 74 Endnotes Introduction and summary Most modern presidents have found that the transition from campaigning to governing presents a unique set of challenges, especially regarding their newfound national security responsibilities. Regardless of their party affiliation or preferred diplomatic priorities, presidents have invariably come to appreciate that they can- not afford to make foreign policy decisions in the same manner as they did when they were a candidate. The requirements of managing an enormous and complex national security bureau- cracy reward careful deliberation and strategic consistency, while sharply punishing the kind of policy shifts that are more common on the campaign trail. Statements by the president are taken far more seriously abroad than are promises by a candidate, by both allies and adversaries alike. And while policy mistakes made before entering office can damage a candidate’s personal political prospects, a serious misstep made once in office can put the country itself at risk. -

Suga and Biden Off to a Good Start

US-JAPAN RELATIONS SUGA AND BIDEN OFF TO A GOOD START SHEILA A. SMITH, COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS CHARLES T. MCCLEAN , UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The early months of 2021 offered a full diplomatic agenda for US-Japan relations as a new US administration took office. Joe Biden was sworn in as the 46th president of the United States amid considerable contention. Former President Donald Trump refused to concede defeat, and on Jan. 6, a crowd of his supporters stormed the US Capitol where Congressional representatives were certifying the results of the presidential election. The breach of the US Capitol shocked the nation and the world. Yet after his inauguration on Jan. 20, Biden and his foreign policy team soon got to work on implementing policies that emphasized on US allies and sought to restore US engagement in multilateral coalitions around the globe. The day after the inauguration, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan reached out to his counterpart in Japan, National Security Secretariat Secretary General Kitamura Shigeru, to assure him of the importance the new administration placed on its allies. The COVID-19 pandemic continued to focus the attention of leaders in the United States and Japan, however. This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 23, No. 1, May 2021. Preferred citation: Sheila A. Smith and Charles T. McClean, “US-Japan Relations: Suga and Biden Off to a Good Start,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp 21-28. US- JAPAN RELATIONS | M AY 202 1 21 Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide faced rising on Asian allies and on the primacy of the US- numbers of infections, declaring a second state Japan partnership. -

Mapping the Jihadist Threat: the War on Terror Since 9/11

Campbell • Darsie Mapping the Jihadist Threat A Report of the Aspen Strategy Group 06-016 imeless ideas and values,imeless ideas contemporary dialogue on and open-minded issues. t per understanding in a nonpartisanper understanding and non-ideological setting. f e o e he mission ofhe mission enlightened leadership, foster is to Institute Aspen the d n T io ciat e r p Through seminars, policy programs, initiatives, development and leadership conferences the Institute and its international partners seek to promote the pursuit of the pursuit partners and its international promote seek to the Institute and ground common the ap Mapping the Jihadist Threat: The War on Terror Since 9/11 A Report of the Aspen Strategy Group Kurt M. Campbell, Editor Willow Darsie, Editor u Co-Chairmen Joseph S. Nye, Jr. Brent Scowcroft To obtain additional copies of this report, please contact: The Aspen Institute Fulfillment Office P.O. Box 222 109 Houghton Lab Lane Queenstown, Maryland 21658 Phone: (410) 820-5338 Fax: (410) 827-9174 E-mail: [email protected] For all other inquiries, please contact: The Aspen Institute Aspen Strategy Group Suite 700 One Dupont Circle, NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 736-5800 Fax: (202) 467-0790 Copyright © 2006 The Aspen Institute Published in the United States of America 2006 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-456-4 Inv No.: 06-016 CONTENTS DISCUSSANTS AND GUEST EXPERTS . 1 AGENDA . 5 WORKSHOP SCENE SETTER AND DISCUSSION GUIDE Kurt M. Campbell Aspen Strategy Group Workshop August 5-10, 2005 . -

ORGANIZING the PRESIDENCY Discussions by Presidential Advisers Back to FDR

A Brookings Book Event STEPHEN HESS BOOK UPDATED: ORGANIZING THE PRESIDENCY Discussions by Presidential Advisers back to FDR The Brookings Institution November 14, 2002 Moderator: STEPHEN HESS Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, Brookings; Eisenhower and Nixon Administrations Panelists: HARRY C. McPHERSON Partner - Piper, Rudnick LLP; Johnson Administration JAMES B. STEINBERG V.P. and Director, Foreign Policy Studies, Brookings; Clinton Administration GENE SPERLING Senior Fellow, Economic Policy, and Director, Center on Universal Education, Council on Foreign Relations; Clinton Administration GEORGE ELSEY President Emeritus, American Red Cross; Roosevelt, Truman Administrations RON NESSEN V.P. of Communications, Brookings; Ford Administration FRED FIELDING Partner, Wiley Rein & Fielding; Nixon, Reagan Administrations Professional Word Processing & Transcribing (801) 942-7044 MR. STEPHEN HESS: Welcome to Brookings. Today we are celebrating the publication of a new edition of my book “Organizing the Presidency,” which was first published in 1976. When there is still interest in a book that goes back more than a quarter of a century it’s cause for celebration. So when you celebrate you invite a bunch of your friends in to celebrate with you. We're here with seven people who have collectively served on the White House staffs of eight Presidents. I can assure you that we all have stories to tell and this is going to be for an hour and a half a chance to tell some of our favorite stories. I hope we'll be serious at times, but I know we're going to have some fun. I'm going to introduce them quickly in order of the President they served or are most identified with, and that would be on my right, George Elsey who is the President Emeritus of the American Red Cross and served on the White House staff of Franklin D. -

Launching a New Institution: PACIFIC COUNCIL on INTERNATIONAL POLICY

Launching A New Institution: PACIFIC COUNCIL ON INTERNATIONAL POLICY 1995-1996 Launching a New Institution: The Pacific Council on International Policy 1995-1996 Established in cooperation with the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc. To the Members of the Pacific Council 1 on International Policy Launching a New Institution 2 Programs and Meetings 15 Visiting Scholars and Fellows Program 24 Board of Directors 25 Corporate sponsors 26 Individual Contributions 27 General and Program Support 29 Membership Policy 30 Membership Roster 31 Staff 36 Pacific Council on International Policy University of Southern California Los Angeles, California 90089-0035 (phone) 213-740-4296 (fax) 213-740-9498 (e-mail) [email protected] To the members of the Pacific Council on International Policy n two years, the Pacific Council on International Policy has moved from a compelling vision to a vigorous and extraordinarily promising organization. We have made rapid progress in Iestablishing a leadership forum which will attract the participation of thoughtful and concerned leaders from throughout the western region of North America and around the entire Pacific Rim. The Pacific Council’s founding and charter members believe that there is a clear and urgent need for an international policy organization rooted in the strengths of the western United States — its leaders, resources and diversity — but which will consistently and creatively look outward to the kinds of relationships that should be developed with our neighbors to the west in the Asia Pacific region and south in Latin America. It is essential to bring together a broad based group of leaders from around the Pacific Rim to consider the challenges that face us all and to make recommendations for policies that would contribute to growth and stability. -

CRS Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code RL30341 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China/Taiwan: Evolution of the “One China” Policy – Key Statements from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei Updated March 12, 2001 Shirley A. Kan Specialist in National Security Policy Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress This CRS Report was initiated upon a request from Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott in the 106th Congress. China/Taiwan: Evolution of the “One China” Policy – Key Statements from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei Summary On July 9, 1999, questions about the “one China” policy arose again after Lee Teng-hui, then-President of Taiwan, characterized cross-strait relations as “special state-to-state ties.” The Clinton Administration responded that Lee’s statement was not helpful and reaffirmed the “one China” policy and opposition to “two Chinas.” Beijing, in February 2000, issued its second White Paper on Taiwan, reaffirming its “peaceful unification” policy but with new warnings about the risk of conflict. There also have been questions about whether and how President Chen Shui-bian, inaugurated in May 2000, might adjust Taiwan’s policy toward the Mainland. In Part I, this CRS report discusses the policy on “one China” since the United States began in 1971 to reach understandings with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) government in Beijing. Part II documents the evolution of the “one China” principle as articulated in key statements by Washington, Beijing, and Taipei. Despite apparently consistent statements over almost three decades, the critical “one China” principle has been left somewhat ambiguous and subject to different interpretations among Washington, Beijing, and Taipei. -

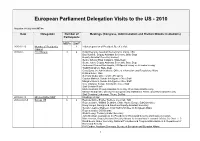

The Information Below Is Based on the Information Supplied to EPLO and Stored in Its Archives and May Differ from the Fina

European Parliament Delegation Visits to the US - 2010 Situation: 01 July 2010 MT/mt Date Delegation Number of Meetings (Congress, Administration and Bretton-Woods Institutions) Participants MEPs Staff* 2010-02-16 Member of President's 1 Initial preparation of President Buzek´s Visit Cabinet 2010-02- ECR Bureau 9 4 David Heyman, Assistant Secretary for Policy, TSA Dan Russell, Deputy Assistant Secretary ,State Dept Deputy Assistant Secretary Limbert, Senior Advisor Elisa Catalano, State Dept Stuart Jones, Deputy Assistant Secretary, State Dept Ambassor Richard Morningstar, US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Todd Holmstrom, State Dept Cass Sunstein, Administrator, Office of Information and Regulatory Affiars Kristina Kvien, NSC Sumona Guha, Office of Vice-President Gordon Matlock, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Margaret Evans, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Clee Johnson, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Staff Senator Risch Mark Koumans, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Dept Homeland Security Michael Scardeville, Director for European and Multilateral Affairs, Dept Homeland Security Staff Senators Lieberman, Thune, DeMint 2010-02-18 Mrs Lochbihler MEP 1 Meetings on Iran 2010-03-03-5 Bureau US 6 2 Representative Shelley Berkley, Co-Chair, TLD Representative William Delahunt, Chair, House Europe SubCommittee Doug Hengel, Energy and Sanctions Deputy Assistant Secretary Senator Jeanne Shaheen, Chair Subcommittee on European Affairs Representative Cliff Stearns Stuart Levey, Treasury Under Secretary John Brennan, Assistant to the President for -

The Herzstein Texas National Security Forum Brought to You by the Moody Foundation

THE HERZSTEIN TEXAS NATIONAL SECURITY FORUM BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE MOODY FOUNDATION “SECURITY IN TRANSITION: NATIONAL SECURITY CHALLENGES FACING THE NEXT PRESIDENT” SEPTEMBER 21ST - 23RD, 2016 • UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Sponsored by: moody foundation; herzstein foundation Hosted by: clements center for national security; strauss center for international security and law; the white house transition project; rice university's baker institute for public policy; lbj presidential library; center for politics and governance; lbj school of public affairs Location: university of texas at austin (etter-harbin alumni center and lbj presidential library) Thursday, September 22 - Etter-Harbin Alumni Center Ballroom National Security Issues Confronting the Next President 9:00 – 10:15 am Session 1 : Asia Moderator: Rana Siu Inboden, Distinguished Scholar, Strauss Center for International Security and Law, University of Texas at Austin Panelists: Michael Green, former Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Asian Affairs at the National Security Council Philip Zelikow, former Counselor, Department of State 1 10:30 – 11:45 am Session 2 : Middle East Moderator: Lawrence Wright, Author and staff writer for The New Yorker magazine Panelists: James Jeffrey, former Deputy National Security Advisor and former Ambassador to Iraq, Turkey, and Albania Kimberly Kagan, Founder and President of the Institute for the Study of War Derek Chollet, former Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs 12:00 – 1:30 pm Lunch and Conversation on National Security Challenges Facing the Next President Moderator: Robert Chesney, Director of the Strauss Center for International Security and Law, University of Texas at Austin Panelists: William McRaven, Chancellor of the University of Texas System and former Commander of U.S. -

Important Figures in the NSC

Important Figures in the NSC Nixon Administration (1969-1973) National Security Council: President: Richard Nixon Vice President: Spiro Agnew Secretary of State: William Rogers Secretary of Defense: Melvin Laird Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (APNSA): Henry Kissinger Director of CIA: Richard Helms Chairman of Joint Chiefs: General Earle Wheeler / Admiral Thomas H. Moorer Director of USIA: Frank Shakespeare Director of Office of Emergency Preparedness: Brig. Gen. George Lincoln National Security Council Review Group (established with NSDM 2) APNSA: Henry A. Kissinger Rep. of Secretary of State: John N. Irwin, II Rep. of Secretary of Defense: David Packard, Bill Clements Rep. of Chairman of Joint Chiefs: Adm. Thomas H. Moorer Rep. of Director of CIA: Richard Helms, James R. Schlesinger, William E. Colby National Security Council Senior Review Group (NSDM 85—replaces NSCRG/ NSDM 2) APNSA: Henry A. Kissinger Under Secretary of State: Elliott L. Richardson / John N. Irwin, II Deputy Secretary of Defense: David Packard / Bill Clements Director of Central Intelligence: Richard Helms Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: General Earle Wheeler / Admiral Thomas H. Moorer Under Secretary’s Committee: Under Secretary of State: Elliott L. Richardson / John N. Irwin, II APNSA: Henry Kissinger Deputy Secretary of Defense: David Packard / Bill Clements Chairman of Joint Chiefs: Gen. Earle G. Wheeler / Adm. Thomas H. Moorer Director of CIA: Richard M. Helms Nixon/Ford Administration (1973-1977) National Security Council: President: Richard Nixon (1973-1974) Gerald Ford (1974-1977) Vice President: Gerald Ford (1973-1974) Secretary of State: Henry Kissinger Secretary of Defense: James Schlesinger / Donald Rumsfeld APNSA: Henry Kissinger / Brent Scowcroft Director of CIA: Richard Helms / James R. -

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 The Honorable Sally Yates Acting Attorney General Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530 The Honorable Thomas A. Shannon Acting Secretary Department of State 2201 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20520 Secretary Kelly, Acting Attorney General Yates, Acting Secretary Shannon: As former cabinet Secretaries, senior government officials, diplomats, military service members and intelligence community professionals who have served in the Bush and Obama administrations, we, the undersigned, have worked for many years to make America strong and our homeland secure. Therefore, we are writing to you to express our deep concern with President Trump’s recent Executive Order directed at the immigration system, refugees and visitors to this country. This Order not only jeopardizes tens of thousands of lives, it has caused a crisis right here in America and will do long-term damage to our national security. In the middle of the night, just as we were beginning our nation’s commemoration of the Holocaust, dozens of refugees onboard flights to the United States and thousands of visitors were swept up in an Order of unprecedented scope, apparently with little to no oversight or input from national security professionals. Individuals, who have passed through multiple rounds of robust security vetting, including just before their departure, were detained, some reportedly without access to lawyers, right here in U.S. airports. They include not only women and children whose lives have been upended by actual radical terrorists, but brave individuals who put their own lives on the line and worked side-by-side with our men and women in uniform in Iraq now fighting against ISIL. -

Us-China Relations from Tiananmen to Trump

The Strategist Texas National Security Review: Volume 3, Issue 1 (Winter 2019/2020) Print: ISSN 2576-1021 Online: ISSN 2576-1153 WHAT WENT WRONG? U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS FROM TIANANMEN TO TRUMP James B. Steinberg What Went Wrong? U.S.-China Relations from Tiananmen to Trump James Steinberg looks back at the relationship between the United States and China over the last 30 years and asks whether a better outcome could have been produced had different decisions been made. This essay is adapted from the Ernest May Lec- the Cold War? And, since this is an election year, ture delivered on Aug. 3, 2019, at the Aspen Strat- the question quickly morphs into the all too famil- egy Group. iar, “Who is to blame”?5 For some, this trajectory of Sino-American rela- here are few things that Democrats and tions is not surprising. Scholars such as John Mear- Republicans in Washington agree on sheimer have long argued that conflict between these days — but policymakers from the United States and China is unavoidable — a both parties are virtually unanimous in product of the inherent tensions between an es- theT view that Sino-American relations have taken tablished and rising power.6 If we accept this view, a dramatic turn for the worse in recent years. In then the policy question — both with regard to the the span of just about one decade, we have seen past and to the future — is not how to improve what was once hailed as a budding strategic “part- Sino-American relations but rather how to prevail nership”1 transformed into “a geopolitical compe- in the foreordained contest.