"Gay" and "Straight" Rodeo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hat in the Wind

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 83 CutBank 83 Article 8 Spring 2015 A Hat in the Wind Emry McAlear Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McAlear, Emry (2015) "A Hat in the Wind," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 83 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss83/8 This Prose is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. emry Mcalear a hat in the wind A couple years before I started riding bulls, I moved back to my home town of Twin Bridges, Montana to help my father with his failing pharmacy. Since I was a college graduate, single, broke, and living with my dad, I felt like a failure. It was one of the most depressing periods in my life but eventually I found the rodeo arena. I started riding bulls and for the first time in a long while, I felt like I was worthy. Rodeo is not like other sports. In most sports, the athlete shares the stage with many other people at the same time. In basketball, football, baseball, and track and field, there is never a time when a participant can be confident that every single spectator is watching nobody else but him. In rodeo, every competitor gets his or her moment in the sun. -

78Th Annual Comanche Rodeo Kicks Off June 7 and 8

www.thecomanchechief.com The Comanche Chief Thursday, June 6, 2019 Page 1C 778th8th AAnnualnnual CComancheomanche RRodeoodeo Comanche Rodeo in town this weekend Sponsored The 78th Annual Comanche Rodeo kicks off June 7 and 8. The rodeo is a UPRA and CPRA sanctioned event By and is being sponsored by TexasBank and the Comanche Roping Club Both nights the gates open at 6:00 p.m. with the mutton bustin’ for the youth beginning at 7:00 p.m. Tickets are $10 for adults and $5 for ages 6 to 12. Under 5 is free. Tickets may be purchased a online at PayPal.Me/ ComancheRopingClub, in the memo box specify your ticket purchase and they will check you at the gate. Tickets will be available at the gate as well. Friday and Saturday their will be a special performance at 8:00 p.m. by the Ladies Ranch Bronc Tour provided by the Texas Bronc Riders Association. After the rodeo on both nights a dance will be featured starting at 10:00 p.m. with live music. On Friday the Clint Allen Janisch Band will be performing and on Saturday the live music will be provided by Creed Fisher. On Saturday at 10:30 a.m. a rodeo parade will be held in downtown Comanche. After the parade stick around in downtown Comanche for ice cream, roping, stick horse races, vendor booths and food trucks. The parade and events following the parade are sponsored by the Comanche Chamber of Commerce. Look for the decorated windows and bunting around town. There is window decorating contest all over town that the businesses are participating in. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 29th Legislature Third Session Alberta Hansard Wednesday morning, November 15, 2017 Day 54 The Honourable Robert E. Wanner, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 29th Legislature Third Session Wanner, Hon. Robert E., Medicine Hat (NDP), Speaker Jabbour, Deborah C., Peace River (NDP), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Sweet, Heather, Edmonton-Manning (NDP), Deputy Chair of Committees Aheer, Leela Sharon, Chestermere-Rocky View (UCP), Luff, Robyn, Calgary-East (NDP) Deputy Leader of the Official Opposition MacIntyre, Donald, Innisfail-Sylvan Lake (UCP) Anderson, Hon. Shaye, Leduc-Beaumont (NDP) Malkinson, Brian, Calgary-Currie (NDP) Anderson, Wayne, Highwood (UCP) Mason, Hon. Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (NDP), Babcock, Erin D., Stony Plain (NDP) Government House Leader Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (UCP) McCuaig-Boyd, Hon. Margaret, Bilous, Hon. Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (NDP) Dunvegan-Central Peace-Notley (NDP) Carlier, Hon. Oneil, Whitecourt-Ste. Anne (NDP) McIver, Ric, Calgary-Hays (UCP), Carson, Jonathon, Edmonton-Meadowlark (NDP) Official Opposition Whip Ceci, Hon. Joe, Calgary-Fort (NDP) McKitrick, Annie, Sherwood Park (NDP) Clark, Greg, Calgary-Elbow (AP) McLean, Hon. Stephanie V., Calgary-Varsity (NDP) Connolly, Michael R.D., Calgary-Hawkwood (NDP) McPherson, Karen M., Calgary-Mackay-Nose Hill (AP) Coolahan, Craig, Calgary-Klein (NDP) Miller, Barb, Red Deer-South (NDP) Cooper, Nathan, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (UCP) Miranda, Hon. Ricardo, Calgary-Cross (NDP) Cortes-Vargas, Estefania, Strathcona-Sherwood Park (NDP), Nielsen, Christian E., Edmonton-Decore (NDP) Government Whip Nixon, Jason, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre (UCP), Cyr, Scott J., Bonnyville-Cold Lake (UCP) Leader of the Official Opposition, Dach, Lorne, Edmonton-McClung (NDP) Official Opposition House Leader Dang, Thomas, Edmonton-South West (NDP) Notley, Hon. -

February 1999-Vol. VII, No.1 TTABLEABLE OFOF CCONTENTONTENTSS MAGAZINE COMMITTEE OFFICER in CHARGE a Message from the President

February 1999-Vol. VII, No.1 TTABLEABLE OFOF CCONTENTONTENTSS MAGAZINE COMMITTEE OFFICER IN CHARGE A Message From the President............................................................. 1 J. Grover Kelley Features CHAIRMAN For the Kids ...................................................................................... 2 Bill Booher VICE CHAIRMAN Special Delivery................................................................................. 4 Bill Bludworth Come and Get It!.............................................................................. 6 EDITORIAL BOARD Teresa Ehrman Denim Jeans — As American as Cowboys .................................... 8 Kenneth C. Moursund Jr. Peter A. Ruman 1999 Entertainers and Attractions................................................... 10 Marshall R. Smith III Red Raider Research......................................................................... 12 Constance White Todd Zucker Stay Tuned for Full Coverage.......................................................... 14 COPY EDITOR Committee Spotlights Larry Levy Commercial Exhibits........................................................................ 16 PHOTO EDITOR Charlotte Howard Trail Ride........................................................................................... 17 REPORTERS Show News and Updates Nancy Burch Gina Covell 1999 Ticket Turnback Program ................................................... 18 John Crapitto Sue Cruver Beyond the Dome ............................................................................ -

GS Nlwebfeb/Mar03

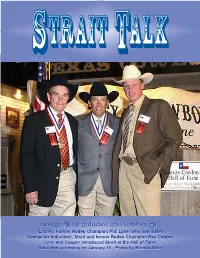

FEBRUARY/MARCH 2003 VOL. 21 NO. 1 George Strait Inducted into Cowboy Hall (L to R): Former Rodeo Champion Phil Lyne (who nominated George for induction), Strait and former Rodeo Champion Roy Cooper. Lyne and Cooper introduced Strait at the Hall of Fame induction ceremony on January 10 - Photo by Brenda Allen Singer George Strait Inducted Into Cowboy Hall of Fame By John Goodspeed Fame members as Ty Murray, world champi- place was his father, James Allen of Santa San Antonio Express-News on all-around cowboy seven times; six-time Anna. FORT WORTH - George Strait won fame all-around cowboy Larry Mahon; eight-time Also honored was one of the longest-run- singing about cowboys. world bull riding champ Don Gray; and four- ning bands in the nation, the Light Crust Now he's in the Texas Cowboy Hall of time world bull riding champion Tuff Doughboys, founded in 1931 by Bob Wills Fame for being one. Hedeman. and Milton Brown. The band was given the Strait, who reached a record 50 No. 1 sin- The other 2003 inductees are Fred Whitfield first Spirit of Texas Award, which celebrates gles last month, was one of six inductees hon- of Hodkley, who won his seventh world the uniqueness of Texas and Texans. ored Friday evening before about 500 guests championship in calf-roping last fall; Guy The Doughboys are nominated for their fifth at the cavernous brick and con- Grammy, for best gospel album, crete museum, at one time a "We Called Him Mr. Gospel horse barn, in the Fort Worth Music: The James Blackwood Stockyards National Historical Tribute Album." District. -

Copyright by Jeannette Marie Vaught 2015

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UT Digital Repository Copyright by Jeannette Marie Vaught 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Jeannette Marie Vaught Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: SCIENCE, ANIMALS, AND PROFIT-MAKING IN THE AMERICAN RODEO ARENA Committee: Janet Davis, Supervisor Randolph Lewis Erika Bsumek Thomas Hunt Elizabeth Engelhardt Susan D. Jones SCIENCE, ANIMALS, AND PROFIT-MAKING IN THE AMERICAN RODEO ARENA by Jeannette Marie Vaught, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Dedication In memory of my grandmother, Jeanne Goury Bauer, who taught me many hard lessons – unyielding attention to detail, complete mastery of the task at hand, and the inviolable values of secretarial skills – and without whose strength of character I would not be here, having written this, and having loved the work. I did not thank you enough. And to Jeannie Waldron, DVM, who taught me when to stop and ask questions, and when to just do something already. Acknowledgements This project has benefitted from helpful contributors of all stripes, near and far, in large and small ways. First, I must thank the institutions which made the research possible: the Graduate School at the University of Texas provided a critical year-long fellowship that gave me the time and freedom to travel in order to conduct this research. -

Construction Continues in Miller

The SINGLE COPY $1.25 tax included ller ress USPS 349-720 Vol. 138 No.M 51 www.themillerpress.com [email protected] PMiller, Hand County, SD 57362 Saturday, Aug. 22, 2020 Sunshine Bible Academy opens for new school year John T. Page Over the past several weeks par- ents, teachers, and administrators engaged in conversations about how and if schools should open. Many school districts decided to open regularly and Sunshine Bible Academy is one of them. Monday, Aug. 17 marked the be- ginning of their 2020 – 2021 school year. According to Superintendent Jason Watson, the fi rst day back Out & About, 5 was “a good start to the school year.” Things for the most part contin- ue as they have in previous years, but according to the school made a few changes in light of the pandem- ic situation. The academy continues to board students and each morn- ing they complete a basic screening test so that the school can take care of any sickness that could arise. All of the paper towel dispensers and water fountains were replaced with hands free versions to limit contact. The cafeteria no longer uses a self- serve salad bar but instead has em- ployees serve it to the students. The school changed its cleaning poli- cy slightly, most notably adding ad- ditional sanitizations to the regular Teaching abroad, 5 routine. The school year ahead is full of uncertainty, but Sunshine Bible Submitted | The Miller Press | August 22, 2020 Academy plans to move ahead do- TYRA GATES won All-Around Senior Cowgirl as well as the Senior Pole Bending event at the State 4-H Finals held last weekend in Fort ing everything they can to keep stu- Pierre. -

Day Sheet MSLBRA

Day Sheet MSLBRA Performance: MSLBRA #24 Brandon 06/10/2017 SR BOY BAREBACK JR GIRL POLE BENDING SR GIRL BARREL RACIN Draw Contestant Back Draw Contestant Back Draw Contestant Back 1MORGAN THOMPSON 3077 7MIKAYLA REEVES 6049 1MADDY COMBEST 6647 SR BOY BULLRIDING 8KAITLYN SANBORN 6236 2BROOK BLAKENEY 6960 Draw Contestant Back 9CHESNIE NEAL 6958 3AUDREY CORLEY 6806 10JULIANA JENNINGS 6657 4TRESSIE JOHNSON 4410 1AUBREY BURT 4955 5KALIE BLACKMON 4167 JR BOY SADDLE STEER SR GIRL POLE BENDING 6KATIE BLACKMON 6684 Draw Contestant Back Draw Contestant Back 7JESSI WHITE 4807 1MADDY COMBEST 6647 1ELIJAH HOLLADAY 5112 2ALAYNA ARINDER 4674 SR TEAM ROPING LW FLAG RACING 3TRESSIE JOHNSON 4410 Draw Contestant Back Draw Contestant Back 4SKYLAR GLENN 4152 1SKY NEAL 3573 1MOLLIE WALLEY 7938 5BROOK BLAKENEY 6960 BRANDON PETEY 3657 2ROYCE IRBY ROBINSON 7382 6MORGAN TROYER 6340 2MORGAN TROYER 6340 3KOLT HOLLINGSWORTH 7643 BLAKE YOUNG 5984 7AUDREY CORLEY 6806 4CASE CALHOUN 7020 3CODY TROYER 3437 8KALIE BLACKMON 4167 5HANNAH HASTY 7755 DILLON JONES 3961 9BRIANNA YOUNG 6201 6MAGGIE SMITH 7990 4BRENNAN TOMLINSON 3080 10KATIE BLACKMON 6684 TY EDMONDSON 3616 7CARA BETH CALHOUN 7210 5SKYLAR GLENN 4152 8ANABELLE ROBINSON 7957 LW BARREL RACING RIVERS IRBY 3325 9ZAYDA MORGAN 7855 Draw Contestant Back 1ROYCE IRBY ROBINSON 7382 JR TEAM ROPING 10ZOE MORGAN 7719 2HANNAH HASTY 7755 Draw Contestant Back JR BOY FLAG RACING 3CARA BETH CALHOUN 7210 1LOGAN WILSON 6284 Draw Contestant Back JULIANA JENNINGS 6657 4MOLLIE WALLEY 7938 1KADE HOLLINGSWORTH 7754 2KAITLYN SANBORN 6236 -

Gaycalgary and Edmonton Magazine #72, October 2009 Table of Contents Table of Contents

October 2009 ISSUE 72 The Only Magazine Dedicated to Alberta’s GLBT+ Community FREE ALBERTA’s top TEN GLBT FIGURES Part 2 THE PRICE OF OUR HARD-WON RIGHTS THE POLICE SERVICE Are GLBT Trust Issues Unfounded? COMMUNITY DIRECTORY • MAP AND EVENTS • TOURISM INFO >> STARTING ON PAGE 17 GLBT RESOURce • CALGARy • EDMONTon • ALBERTA www.gaycalgary.com GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine #7, October 009 Table of Contents Table of Contents Publisher: ................................Steve Polyak 5 Homowners Editor: ...............................Rob Diaz-Marino Publisher’s Column Graphic Design: ................Rob Diaz-Marino Sales: .......................................Steve Polyak 8 A Visit to Folsom Street Fair Writers and Contributors Mercedes Allen, Chris Azzopardi, Dallas 9 Apollo & Team Edmonton Curling Barnes, Antonio Bavaro , Camper British, “Chess on Ice” Returns for Another Season 8 Dave Brousseau, Sam Casselman, Jason Clevett, Andrew Collins, James S.M. Demers, Rob Diaz-Marino, Jack Fertig, AGE Glen Hanson, Joan Hilty, Evan Kayne, 11 The Police Service P Boy David, Richard Labonte, Stephen Are GLBT Trust Issues Unfounded? Lock, Allan Neuwirth, Steven Petrow, Steve Polyak, Pam Rocker, Romeo San Vicente, Diane Silver, D’Anne Witkowski, Dan Woog, 13 Chelsea Boys and the GLBT Community of Calgary, Edmonton, and Alberta. 14 Out of Town Palm Springs, California Photography Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino and Jason Clevett. 17 Directory and Events Videography Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino 23 Letters to the Editor 11 Printers 24 It’s About Pride...And -

Rodeo Clowns--- the Rodeo Clown and Bullfighter Are the Book

ONLY o C nnors Sta te college t ·b Rt. 1, Box 1000 ' rary PAID BULK RATE Warne,, Oiluom 446H7as PERMIT#l7 a T WARNER, OK 74469 Forwarding & Address Correction Requested • The Warner tar ews Serving • Keefeton • Gore • Porum • WarnerlV • Webbers Falls - Call (918) 463-2386 or Fax us at (918) 773-8745 Volume IX-Issue No. 34 FAX# (918) 773-8745 (918) 463-2386 Wednesday, June 14, 1995 Local resident graduates from academy Graduation and commission Records fall in local race ing ceremonies for the 48th Okla homa HighwayPattolAcademy were No record times were broken held May 30, 1995 forthe forty-nine in the annual race held at the library, cadets who successfully completed but a record crowd of 73 participants seventeen weeks of intensive train entered their turtles in the turtle race, ing at the Oklahoma Highway Patrol held last Thursday afternoon at the training facility in Oklahoma City. WarnerPublic Library. Sixty-five cadets originally started The "meet" started at 2 pm. the Academy training. Governor under dry and muggy conditions with Frank Keating gave the graduation many anxious kids and parentsawait address and the oath of office was ing the 'heat' races. given by the Honorable Judge Alma The contestants were divided Wilson, Oklahoma Supreme Court up into groups, with six groups of ten Justice. Approximately five hundred turtles, followedby two more groups people attended the graduation. of six and seven turtles, respectively. Overbey is a graduate of The turtles were numberedand Warner High School and Connors Trooper Bill Overbey as each group was scheduled to race, State College and attended North- as an Officer at Eddie Warrior Cor contestants brought their 'sprinters' eastem State University, Muskogee rectional Center. -

Official Entry Blank

HYDE/HAND 4-H RODEO 4-H Back # Sunday, June 27, 2021 _________ Starts at 9 A.M. – Check in 8am ***ENTRIES POSTMARKED NO LATER THAN JUNE 4, 2021*** NO LATE ENTRIES. Entry blanks will be returned if not completed fully or have no money enclosed NAME(please print)_____________________________________________AGE(Jan 1, 2021)_________ BIRTH DATE_______________ ADDRESS _________________________________CITY _________________________STATE_________ZIP CODE______________ PHONE # __________________________ EMAIL ADDRESS____________________________________________________________ PARENT/GUARDIAN NAME(please print) ___________________________________________________________________________ Open to senior boys and girls age’s 14-19 years of age as of 1/1/21 SENIOR BOYS EVENTS SENIOR GIRLS EVENTS FEES PARENT SIGNATURE FEES PARENT SIGNATURE ( ) Bareback Riding $23.00 _____________________ ( ) Barrel Racing $18.00 _____________________ ( ) Saddle Bronc $23.00 _____________________ ( ) Breakaway Roping $20.00 _____________________ ( ) Steer Wrestling $20.00 _____________________ ( ) Goat Tying $18.00 _____________________ ( ) Calf Roping $20.00 _____________________ ( ) Pole Bending $18.00 _____________________ ( ) Bull Riding $23.00 _____________________ ( ) Ribbon Roping $20.00 _____________________ ( ) Team Roping $20.00 _____________________ ( ) Team Roping $20.00 _____________________ List Header Name _________________________________________ List Heeler Name ___________________________________ IS YOUR PARTNER ENTERED IN THE RODEO??? PLEASE DOUBLE -

The History of Women in Rodeo by Cindy Lea Bahe Many Sports in Today's World Are Open to Both Sexes, Yet Rodeo Was One Of

The History of Women in Rodeo By Cindy Lea Bahe Many sports in today’s world are open to both sexes, yet rodeo was one of the first sports to include females. Though rodeo was dominated by men, from 1890‐1942, more than four‐hundred women had professional rodeo careers in saddle bronc riding, steer roping, relay riding and trick riding. However, rodeo didn’t discriminate on gender and it certainly posed risks to men and women alike. In 1929 at the Pendleton, Oregon Round Up, veteran bronc rider Bonnie McCarroll was thrown and trampled to death. Following that tragic incident, many rodeos banned women from competing. In 1929 the Rodeo Association of America (RAA) was formed but women were banned from participating. The Cowboys’ Turtle Association was formed in 1936 but women were also banned from competing. Despite their limitations, women continued to compete in smaller rodeos across the country. Eventually they formed the Girls Rodeo Association (GRA) in 1948. It took two more decades of lobbying to participate in barrel racing and in 1967, this event became official for women at the PRCA’s National Finals Rodeo (NFR). The GRA was later renamed in 1982 as the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA). Barrel racing became the dominant rodeo sport for women also offering the largest payoff, though women also competed in tie down, team and breakaway roping. Mattie Goff Newcombe was a famous trick rider and travelled around the world. She won several All‐ Around Cowgirl Championships and Trick Rider Titles through her career. Mattie has a special section on the first floor of the Casey Tibbs Rodeo Center which displays her memorabilia and actual 1920’s horse trailer alongside a 40‐foot mural of her former Cheyenne River ranch.