Great Estates Economic Impact Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder: the New York Botanical Garden's Legacy Of

Moore in America: Monumental Sculpture at The New York Botanical Garden May 24 – November 2, 2008 Backgrounder: The New York Botanical Garden’s Legacy of Natural and Designed Landscapes The New York Botanical Garden, a 250-acre site that has been designated a National Historic Landmark, offers a wealth of beautiful landscapes, including a hardwood Forest, ponds, lakes, streams, rolling hills with dramatic rock outcroppings carved by glaciers, and New York City’s only freshwater river, which runs through the heart of the Forest in a magnificent rock gorge. These picturesque natural features have been further enhanced by more than a century of artful plantings, gardens, and landscapes designed by the nation’s leading landscape architects and garden designers. As a result of both its natural and human legacies, the Botanical Garden today offers an exceptional setting for outdoor sculpture. Scenic beauty and stunning natural features Following the New York State Governor’s approval on April 28, 1891, of The New York Botanical Garden Act of Incorporation, a site needed to be selected for the location of this new educational and scientific institution. Selection turned to an undeveloped park in the central Bronx. In 1887, a published description of this area notes, “it would be difficult to do justice to the exquisite loveliness of this tract without seeming to exaggerate…gigantic trees, centuries old, crown these summits, while great moss and ivy-covered rocks project here and there at different heights above the surface of the water, increasing the wildness of the science.” An 1893 newspaper account describes the romantic vistas of an old stone house, snuff mill, and other artifacts of previous land use, while surrounded with “almost every tree known to the American forest in the Northern clime.” The underlying bedrock, dark gray Fordham gneiss, shapes many rock outcrops, rolling hills, and steep slopes, ranging from 20 to 180 feet above sea level. -

Annual Report. Mergenthaler Linotype Company

Annual report. Mergenthaler Linotype Company. Brooklyn, N.Y., The Co. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35556003385879 Public Domain, Google-digitized http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google We have determined this work to be in the public domain, meaning that it is not subject to copyright. Users are free to copy, use, and redistribute the work in part or in whole. It is possible that current copyright holders, heirs or the estate of the authors of individual portions of the work, such as illustrations or photographs, assert copyrights over these portions. Depending on the nature of subsequent use that is made, additional rights may need to be obtained independently of anything we can address. The digital images and OCR of this work were produced by Google, Inc. (indicated by a watermark on each page in the PageTurner). Google requests that the images and OCR not be re-hosted, redistributed or used commercially. The images are provided for educational, scholarly, non-commercial purposes. U NL .NB S. _HY Y _ Y W ._ .1 _. _ H. M . ‘ . ¢. ‘ . '0 _if I ;n:h$3...u.?.......~ Wu I . ‘ .. W ..~.! . _ , . , . J 1» » . W“L 2 . »_..-.¢.~».1M..Y.‘ ..‘~...L».\».»&,mw<..¢m-“Rm:. M-_._m.u ..3.*.m.T~3.T~..7.$-.-1.... J2 >-“J . .1.‘$~J$J_.\_.... A ‘ 1,3. I" .. O . IE2. .. ‘ . 333.3..,:»$...a..\...I.a~ \:._1.3 §,_ ! r!! O.. ...."..... 2.. ,!!"».m.." r». On..r‘..r....». b . > - . 3.1 : x w .. _. ... - , . A.‘ .. I Yd. ‘ , .. ... a .. .. v . < . 17%r__.. .a a .» ..4"_ .. 1n.. » .. I 1 , o. -

Prospect Park Primary Source Packet

PROSPECT PARK PRIMARY SOURCE PACKET Student Name Prospect Park Primary Source Packet INTRODUCTORY READING "Timeline." Park History. Prospect Park Alliance, Web. 28 Jan 2014. ADAPTATION In 1834, the City of Brooklyn was chartered, and during the next 30 years it became the third largest city in the country, following only New York (Manhattan) and Philadelphia. Thousands of European immigrants settled in the growing city and sprawling farms gave way to homes. At the same time public parks were gaining popularity in America. Beginning in 1858, the design team of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux transformed more than 800 acres of jagged rock into Central Park in Manhattan. It was the first landscaped public park in the United States. Soon after a movement grew in Brooklyn for a park of its own. Leading the effort was James Stranahan, a businessman and civic leader. In the early 1860s, Stranahan argued that a park in Brooklyn "would become a favorite resort for all classes of our community, enabling thousands to enjoy pure air, with healthful exercise, at all seasons of the year…." Calvert Vaux sketched Prospect Park’s present layout for Stranahan. Vaux convinced Olmsted to join the effort, and construction of the park began on July 1, 1866 under their supervision. Olmsted and Vaux’s plan included rolling green meadows, carriage drives with scenic lookouts, waterfalls, springs and a forest. Organized sports gained popularity throughout the first half of the 1900s and the Park continued to host parades and celebrations that drew huge crowds. Parks Commissioner Robert Moses opened the zoo, bandshell and several playgrounds in the 1930s. -

Ophir Farm History R5

Ophir Farm and Manhattanville College Dear Visitor: Dating back to the 17th century, the story of Ophir Farm combines just the right mix of historical truth and local legend, and serves as a worthy heritage for Manhattanville College, now on the same site. This booklet provides a glimpse into the history, landscaping and architecture of both and is designed to supplement your walking tour with a chronological background that will make the buildings and scenery come alive. The Ophir Farm estate was once one of the nation’s most prominent model farms, an art form and hobby pursued by affluent farmers in the 1800's. Today, it includes a rich sampling from artisans who have worked on New York City’s Central Park, the White House, the Capitol, the campuses of Harvard and Columbia, St. Patrick's Cathedral and Lincoln Center. Our guide has been created, in part, to celebrate and preserve these treasures. Gayl Braisted compiled many of the sources in this history for her Masters thesis at Manhattanville. She was extremely generous with her time and allowed portions of her thesis to be printed herein. For more information about how you can help preserve Ophir Farm, please write to me at Manhattanville College, 2900 Purchase Street, Purchase, NY 10577 or call 914-323-5288. Sincerely, Anne Gold Community Relations Director Index Chronology 1695: Harrison’s Purchase, Arrival of Haviland Family 3 1772: Purchase Street 3 1864: The Holladays 3 1883-1886: John Roach, Arrival of the Reids 5 1887: Design by Frederick Olmsted 6 1888: Fire at Ophir Farm -

Eureka Du 1200 State Street, Utica 13502 NY Ydux5

Name: Eureka Du Address: 1200 State Street, Utica 13502 NY Email: [email protected] Typography and Information Design PrattMWP College of Art and Design Class #1 Professor: Christina Sharp Content 1.creative brief 4.ideation 2.research 5.development 3.inspiration 6.conclusions Creative Brief In this map project we are selecting a New York State Park, and redesign an engaging and exciting map for the park in Adobe Illustrator for potential visitors through compositions, symbols, icon systems, labels, illustrations, and colors. The redesigned map should be practical and able to be used in the real world. My choice on the New York State Park is the Central Park in Manhatten New York. I Chose Central Park because of my own experience. As a first time visitor in New York last year, I visited Central Park with my cousin who has been living in NewYork for seven years. While I was doing my research, I did not find any map for first-time visitors from the central park official website. If I were on my own while I first visited Central Park, I would not be able to know where to begin my visit. I am sure that the other first-time visitors would have the same problem. These are the reasons that my map is designed for first-time visitors who have a limited amount of time. In my map, I featured several top attractions in and around the park. I also included some top-rated restaurants around and inside the park since Knowing where to consume good food is essential during visiting. -

Annual Report

'01 OF NURSING LIBRARY HOSPITAL . LUKE’S grO'^Q ©fje Ikbentietf) Annual Report Hufee’g Hospital J&eto gorfe jfor t fje §?ear Cnbing September 30, 1928 CONTENTS PAGE Officers of St. Luke’s Hospital 3 Managers of St. Luke’s Hospital 4 Standing Committees 5 Members of the Society of St. Luke’s Hospital 6 Life Members 6 Members Paying Annual Dues 7 Officers of Social Service, Members of Executive Board 8 House Officers 10 Medical and Surgical Staff 12 Officers and Standing Committees of the Medical Board for 1928 16 Members of the House Staff 17 Pathological Department 18 Out-Patient Department 19 The Seventieth Annual Report of the Board of Managers of St. Luke’s Hospital 24 Sundry Donations 30 List of Subscriptions to the Century Fund 31 Annual Subscriptions for the Support of Beds 32 Donations received through Superintendent 32 Income and Expenditure Account 40 Hospital Properties and Equipment 42 Unrestricted Funds 43 Endowment Fund and Funds for Designated Purposes 44 Special Appeal Facing page 46 Report of the Committee on Training School 48 Superintendent’s Report 51 Occupations of Patients 55 Applications Declined 56 Expense and Revenue Statement for Fiscal Year 57 Method of Computing Cost of Out-Patient Department 67 Pastor's Report 71 Reports of Social Service 73 Endowed Rooms 80 Endowed Beds 80 Terms of Endowment of Beds 100 Special Foundations 101 Special Trust Funds 104 Gifts of Articles 105 Appendix: List of Officers and Members of the Board of Managers of St. Luke’s Hospital and Their Terms of Service 107 Alumni Association 142 Circular of Information 143 List of Graduates of The St. -

October 2011 2011 Fall Forums Explored “FDR’S Inner Circle”

Onnews and notes from Our the franklin d. roosevelt presidential Way library and museum with support from the Roosevelt Institute Online “Day by Day” Chronology Launched FDR PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY n October 15, 2011 the Pare Lorentz A searchable database based primarily on these OCenter at the FDR Library launched a calendar sources is available so that you can new online database of President Roosevelt’s search the chronology by keyword and date. daily schedule: “Franklin D. Roosevelt Day by Day,” www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/daybyday. As a fulfillment of Pare Lorentz’s original vision, Day by Day also includes an interactive timeline The Franklin D. Roosevelt Day by Day Project of additional materials from the Archives of the is an interactive chronology documenting FDR Library to place each day’s calendar into Franklin Roosevelt’s daily schedule as President, larger historical context. These materials include from March 1933 to April 1945. The project scanned photographs, letters and speeches as was inspired by the work of Pare Lorentz, a well as descriptions of events in United States Depression era documentary filmmaker, who and world history. Special thanks to former dedicated much of his life to documenting Roosevelt Library Director Verne Newton FDR’s daily activities as president, and is whose vision and determination started the Day supported by a grant from the New York by Day Project and helped secure the original Community Trust to the Pare Lorentz Center. funding for the Pare Lorentz Center. Day by Day features digitized original calendars ONLINE RESOURCES “Day by Day” website and schedules maintained by the White House These calendars trace FDR’s appointments, Pare Lorentz Center website Usher and the official White House stenographer. -

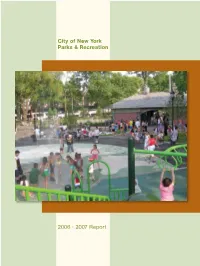

2006 - 2007 Report Front Cover: Children Enjoying a Summer Day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx

City of New York Parks & Recreation 2006 - 2007 Report Front cover: Children enjoying a summer day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx. Back cover: A sunflower grows along the High Line in Manhattan. City of New York Parks & Recreation 1 Daffodils Named by Mayor Bloomberg as the offi cial fl ower of New York City s the steward of 14 percent of New York City’s land, the Department of Parks & Recreation builds and maintains clean, safe and accessible parks, and programs them with recreational, cultural and educational Aactivities for people of all ages. Through its work, Parks & Recreation enriches the lives of New Yorkers with per- sonal, health and economic benefi ts. We promote physical and emotional well- being, providing venues for fi tness, peaceful respite and making new friends. Our recreation programs and facilities help combat the growing rates of obesity, dia- betes and high blood pressure. The trees under our care reduce air pollutants, creating more breathable air for all New Yorkers. Parks also help communities by boosting property values, increasing tourism and generating revenue. This Biennial Report covers the major initiatives we pursued in 2006 and 2007 and, thanks to Mayor Bloomberg’s visionary PlaNYC, it provides a glimpse of an even greener future. 2 Dear Friends, Great cities deserve great parks and as New York City continues its role as one of the capitals of the world, we are pleased to report that its parks are growing and thriving. We are in the largest period of park expansion since the 1930s. Across the city, we are building at an unprecedented scale by transforming spaces that were former landfi lls, vacant buildings and abandoned lots into vibrant destinations for active recreation. -

Central Park:Park: Beautifulbeautiful && Kindkind

NewNew YorkYork CityCity’’ss CentralCentral Park:Park: BeautifulBeautiful && KindKind ByBy DaleDale LaurinLaurin,, RARA PartPart IIIIII SamenessSameness andand Change,Change, FirmnessFirmness andand FlexibilityFlexibility AA Friendship,Friendship, BasedBased onon KindnessKindness andand Criticism,Criticism, SavesSaves thethe ParkPark TheThe StructuresStructures ofof CentralCentral Park:Park: AssertiveAssertive andand YieldingYielding Sameness and Change; Firmness and Flexibility Many people think that Central Park is largely natural, that—as the famous New York Journalist Horace Greeley said on seeing it for the first time: “It’s good they left it alone.” But if Vaux and Olmsted had left the land north of 59th St. as they found it, CentralCentralCentral Park:Park: BeautifulBeautiful && KindKind instead of this vista, CentralCentralCentral Park:Park: BeautifulBeautiful && KindKind we would have this. CentralCentralCentral Park:Park: BeautifulBeautiful && KindKind Hard as it is to believe, Central Park is more a work of art than a product of “mother nature,” and one that called for tremendous effort and made for tremendous change. In his role as construction superintendent, Olmsted mobilized a workforce that numbered hundreds of men, clearing away refuge dumps, dredging swamps, moving tons of earth and rock, excavating—not only for the submerged cross-streets—but for miles of drainage pipe, filling in and preparing the soil, building bridges and park structures, laying down pathways and roads, and planting thousands of trees, shrubs, and plants on this largely barren site—and all according to the Greensward plan. CentralCentralCentral Park:Park: BeautifulBeautiful && KindKind However, the designers didn’t arrogantly change everything. They carefully studied and worked with the topography and existing elements of the site, leaving—for instance—- many of the magnificent rock outcroppings and rugged terrain intact, as natural features. -

A Minnesota Footnote to the 1944 Presidential Election / Barbara

0 A MmNESOm FOOTNOTE TOIHEIMI PRESIDIENTIAL EUEGTION 1 TT most notable event in what proved to be a losing cam Ij OR A SMALL STATE Minnesota has enjoyed paign against popular GOP incumbent Ronald W] unusual prominence in presidential politics of Reagan.' 11 the 20th century. Some cases in point: In the These are, of course, some of the more dramatic turbulent year of 1968 when Vietnam was the focus of Minnesota influences involving the presidency of the political debate, Minnesota Senator Eugene J. Mc United States. There are others, less sweeping in their Carthy, a Democrat, challenged the policy and leader effect, but nonetheless of some interest in completing ship of his own party's incumbent president. Mc the record of Minnesota's mark on the course of Ameri Carthy's win in the New Hampshire primary laid to can presidential politics. This is one such tale. rest the re-election hopes of Lyndon B. Johnson, whose withdrawal from the race opened the door for a contest IN THE SUMMER of 1944 the nations of Europe had between two long-time political cohorts—Senator Mc been at war for five years, the United States and Japan Carthy and Vice-President Hubert H. Humphrey. for nearly three. Franklin D. Roosevelt and Thomas E. Humphrey beat out McCarthy for the Democratic par Dewey were nominated by the Democratic and Repub ty's nomination but lost the election. Two decades be lican parties as contenders for the presidency. Wendell fore, in 1948, another Minnesota political legend was L. Wdlkie, the unsuccessful GOP choice in 1940, bad launched when former governor, Harold E. -

US Foreign-Exchange Operations and Monetary Policy in the Twentieth

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Strained Relations: U.S. Foreign-Exchange Operations and Monetary Policy in the Twentieth Century Volume Author/Editor: Michael D. Bordo, Owen F. Humpage, and Anna J. Schwartz Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-05148-X, 978-0-226-05148-2 (cloth); 978-0-226-05151-2 (eISBN) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bord12-1 Conference Date: n/a Publication Date: February 2015 Chapter Title: Exchange Market Policy in the United States: Precedents and Antecedents Chapter Author(s): Michael D. Bordo, Owen F. Humpage, Anna J. Schwartz Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c13538 Chapter pages in book: (p. 27 – 55) 2 Exchange Market Policy in the United States Precedents and Antecedents 2.1 Introduction Exchange market operations had considerable precedent in policies fol- lowed in Europe during the classical gold standard era from 1870– 1913 and in the gold exchange standard between 1925– 1933. It also had antecedents in US history going back at least to the Wrst decade of the nineteenth century. Under the classical gold standard, the trilemma as outlined in chapter 1 was solved (at least in theory) with perfectly Wxed exchange rates, open capital markets, and no role for monetary policy. However in practice, in the classical era from 1870 to 1913, the assumptions needed to make this work did not hold completely. The classical Humean adjustment mechanism did not work perfectly because wages and prices were not perfectly Xexible, labor was not perfectly mobile, and there were real and Wnancial frictions and shocks. -

Greatestatesflyer2-2

The Great Estates Consortium presents Stewards & Visionaries: Women of the Great Estates An all day symposium Saturday, March 29, 2008 8:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Stewards & Visionaries: Women of the Great Estates When Saturday, March 29, 2008 8:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Where Henry A. Wallace Visitor and Education Center at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site Route 9, Hyde Park, New York Registration fee $55 per person Includes Lunch and Wine & Cheese Reception Presented by The Great Estates Consortium Hosted by Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site Sponsored by The Great Estates Consortium With additional funding provided by: Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area Dutchess County Central Hudson Gas and Tourism Electric Corporation Cover: Portrait of Louise Livingston (1781-1860). Painted posthumously by Theobald Chartran (1849-1907) after an existing miniature. Rome, c. 1872. Gift of J. Dennis Delafield. Historic Hudson Valley. ABOUT THE SYMPOSIUM Stewards and Visionaries: Women of the Great Estates estates and their efforts to save these properties will focus on the importance of women to for future generations. Kenneth Snodgrass, Hudson Valley estates from the 18th to the 20th Executive Director of the Locust Grove Estate, centuries. It will also examine the role that will present a case study focusing on the women played in saving and preserving many of continuing legacy of Annette Innis Young, these important historic properties. Symposium benefactor of two important local history attendees can begin the day by participating in collections in the Hudson Valley, Locust Grove an optional tour of FDR's home, Springwood, and Rosewood in Poughkeepsie, and the Locust and the FDR Presidential Library and Museum.