Romance and Industry on the Road to Avonlea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers Cento Veljanovski CASE ASSOCIATES Current Issues June 1999 Published by the Institute of Public Affairs ©1999 by Cento Veljanovski and Institute of Public Affairs Limited. All rights reserved. First published 1999 by Institute of Public Affairs Limited (Incorporated in the ACT)␣ A.C.N.␣ 008 627 727 Head Office: Level 2, 410 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Phone: (03) 9600 4744 Fax: (03) 9602 4989 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ipa.org.au Veljanovski, Cento G. Pay TV in Australia: markets and mergers Bibliography ISBN 0 909536␣ 64␣ 3 1.␣ Competition—Australia.␣ 2.␣ Subscription television— Government policy—Australia.␣ 3.␣ Consolidation and merger of corporations—Government policy—Australia.␣ 4.␣ Trade regulation—Australia.␣ I.␣ Title.␣ (Series: Current Issues (Institute of Public Affairs (Australia))). 384.5550994 Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute of Public Affairs. Printed by Impact Print, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056 Contents Preface v The Author vi Glossary vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Pay TV Picture 9 More Choice and Diversity 9 Packaging and Pricing 10 Delivery 12 The Operators 13 Chapter Three: A Brief History 15 The Beginning 15 Satellite TV 19 The Race to Cable 20 Programming 22 The Battle with FTA Television 23 Pay TV Finances 24 Chapter Four: A Model of Dynamic Competition 27 The Basics 27 Competition and Programme Costs 28 Programming Choice 30 Competitive Pay TV Systems 31 Facilities-based -

45477 ACTRA 8/31/06 9:50 AM Page 1

45477 ACTRA 8/31/06 9:50 AM Page 1 Summer 2006 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists ACTION! Production coast to coast 2006 SEE PAGE 7 45477 ACTRA 9/1/06 1:53 PM Page 2 by Richard We are cut from strong cloth Hardacre he message I hear consistently from fellow performers is that renegotiate our Independent Production Agreement (IPA). Tutmost on their minds are real opportunities for work, and We will be drawing on the vigour shown by the members of UBCP proper and respectful remuneration for their performances as skilled as we go into what might be our toughest round of negotiations yet. professionals. I concur with those goals. I share the ambitions and And we will be drawing on the total support of our entire member- values of many working performers. Those goals seem self-evident, ship. I firmly believe that Canadian performers coast-to-coast are cut even simple. But in reality they are challenging, especially leading from the same strong cloth. Our solidarity will give us the strength up to negotiations of the major contracts that we have with the we need, when, following the lead of our brothers and sisters in B.C. associations representing the producers of film and television. we stand up and say “No. Our skill and our work are no less valuable Over the past few months I have been encouraged and inspired than that of anyone else. We will be treated with the respect we by the determination of our members in British Columbia as they deserve.” confronted offensive demands from the big Hollywood companies I can tell you that our team of performers on the negotiating com- during negotiations to renew their Master Agreement. -

The Anchor, Volume 114.02: September 13, 2000

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 2000 The Anchor: 2000-2009 9-13-2000 The Anchor, Volume 114.02: September 13, 2000 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_2000 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 114.02: September 13, 2000" (2000). The Anchor: 2000. Paper 14. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_2000/14 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 114, Issue 2, September 13, 2000. Copyright © 2000 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 2000-2009 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 2000 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hope College • Holland, Michigan iervlng the Hope College Community for 114 years Gay film series delayed by administration Provost calls for more Nyenhuis and his dean's council. Wylen Library, GLOBE, Women's August with the dean's council and ries: to create understanding," The series, called the Gay/Les- time to examine is- Issues Organization, Hope Demo- a group of faculty and students as- Nyenhuis said. bian Film Series, was to run from crats, Sexual Harassment Policy sembled by Nyenhuis, Dickie was The original recommendation sues. September 12 to October 19, and Advocates, and the women's stud- told to delay the films. from the dean's council was that the Matt Cook included 5 films on topics ranging ies, psychology, sociology, religion, "Our concern regarding the series series be delayed for an entire year, CAMPUS BEAT EDITOR from growing up gay, to techniques and theater departments. -

Productions in Ontario 2013

SHOT IN ONTARIO 2013 Feature Films – Theatrical A DAUGHTER’S REVENGE Company Name: NB Thrilling Films 5 Inc. Producer: Don Osborne Exec. Producers: Pierre David, Tom Berry, Neil Bregman Director: Curtis Crawford Production Manager: Don Osborne D.O.P.: Bill St. John Key Cast: Elizabeth Gillies, Cynthia Stephenson, William Moses Shooting Dates: Nov 30 – Dec 12/13 A FIGHTING MAN Company: Rollercoaster Entertainment Producers: Gary Howsam, Bill Marks Exec. Producer: Jeff Sackman Line Producer: Maribeth Daley Director: Damian Lee Production Manager: Anthony Pangalos D.O.P.: Bobby Shore Key Cast: Famke Janssen, Dominic Purcell, James Caan, Kim Coates, Michael Ironside, Adam Beach, Louis Gossett Jr., Sheila McCarthy Shooting Dates: Apr 15 – May 15/13 A MASKED SAINT Company: P23 Entertainment Producers: Cliff McDowell, David Anselmo Director: Warren Sonoda Line Producer/Production Manager: Justin Kelly D.O.P.: James Griffith Key Cast: Brett Granstaff, Lara Jean Chorostecki, Diahann Carroll Shooting Dates: Nov 4 – Nov 22/13 BEST MAN HOLIDAY Company: Blackmailed Productions / Universal Pictures Producer: Sean Daniel Exec. Producer: Preston L. Holmes Director: Malcolm Lee Production Manager: Dennis Chapman D.O.P.: Greg Gardiner Key Cast: Terrence Howard, Morris Chestnut, Sanaa Lathan, Nia Long, Taye Diggs Shooting Dates: Apr 8 - May 22/13 BERKSHIRE COUNTY Company: Narrow Edge Productions Producer: Bruno Marino Exec. Producers: Tony Wosk, David Miller Director: Audrey Cummings Production Manager: Paul Roberts D.O.P.: Michael Jari Davidson Key Cast: Alysa King, Madison Ferguson, Cristophe Gallander, Samora Smallwood, Bart Rochon, Aaron Chartrand Shooting Dates: Apr 4 - May 16/13 December 2013 1 SHOT IN ONTARIO 2013 BIG NEWS FROM GRAND ROCK Company: Markham Street Films Producer: Judy Holm, Michael McNamara Director: Daniel Perlmutter Production Manager: Sarah Jackson D.O.P.: Samy Inayeh Key Cast: Aaron Ashmore, Kristin Booth, Art Hindle, Ennis Esmer Shooting Dates: Sep 30 – Oct 24/13 BLUR Company: Black Cat Entertainment Producer: Bruno Marino Exec. -

{PDF EPUB} Anne of Green Gables the Sequel - Screenplay by Kevin Sullivan Anne of Green Gables: the Sequel Screenplay

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Anne of Green Gables The Sequel - Screenplay by Kevin Sullivan Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel Screenplay. In order to succeed, Anne must win over the icy Katherine Brooke and endure tormenting from the snobby Pringle family. Anne finds a kindred spirit in Emmeline Harris who is being raised by her cranky grandmother, Margaret Harris, and wants nothing more than to be loved by her absent father, Morgan Harris. Anne and Emmeline become fast friends, and Anne quickly forces her way into the Harris family and ultimately changes their lives. After a chance encounter with Gilbert, who is now engaged and in medical school in Halifax, Anne begins to re-evaluate what is important to her. A surprise question from Morgan Harris makes Anne realize how much she misses home and she returns to Green Gables soon after the school term has ended. Upon returning, she learns further news about Gilbert and must decide how much he truly means to her. Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel Autographed Screenplay. The script comes enclosed in a display box with a transparent cover. Film Summary: The enchanting sequel to the Emmy Award-winning Anne of Green Gables tells the continuing story of Anne Shirley as she makes the transition from a romantic, impetuous orphan to an outspoken, adventurous, and accomplished young teacher. Canadian actress Megan Follows returns to her role as Anne. Tony Award-winner Colleen Dewhurst stars opposite her as the aging Marilla Cuthbert and Oscar-winning British actress Dame Wendy Hiller appears as the prickly dowager Mrs. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Which Way to the Future? Dancing with Lizards: The

CINEMA CAN •A D A No. 160 FEBRUARY·MARCH 1989 PUBLISHER Jean·Pierre Tadros EDITOR Jean·Pierre Tadros TORONTO EDITOR Tom PenmuHer ASSOCIATE EDITOR Frank Rackow NEWS EDITOR JohnT immins REPORTER Wyndham Wise (Toronto) EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Zachary Ansley, Genevie ve Bujold, Jeremy Mary J. Martin Irons, Jackie Burroughs, Elias Koteas, Myma Bell (tntem) Kerrie Keane, Jan Rubes, Josette Simon, CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Saul Rubinek, Monique Spaziani, Ron White. Michael Dorland COLUMNISTS Michael Bergman, Unda Ean, George L George, Greg Klymkiw, CMs Majka, Chanes Mandel, Mar'< O'Neill, Barbara Sternberg, Pat Thompson PRODUCTION GUIDE Jim Levesque ART DIRECTION ClaireB aron The 1989 Genie nominees for Best Actor/Actress. On the cover are AC8deftIw ......... DINctor ............. President AI Waxm.n and Director of lIIIItlotl... ond eo_unlcMlona ...... Till· .... ADVERTISING Diane Maass (5 t4 ) 272·5354 Marcia Hackbom(416) 596-6829 RhondaO lson (604) 688-6796 Genie turns 10 21 The Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television and its showcase, the Genie awards for Canadian film, are one decade old. Pa t Thompson Founde<l by the Canadian Socie~ 01 looks back over the Academy's first 10 years. As well, Gerald Pratley of the Ontario Film Institute remembers the pre-Academy era of the Cinematographers, is published by the Cinema Canada Ma9azine Foundatlon. President, Canadian Film Awards. And, finally, past winners speak out about what it means to win a Genie. Jean-Pierre Tadros : VICe-President, George Csaba KaUer ; Secretary-Treasurer, Connie . Tadros : Director, George Campbell Miller. The NFB at 50: Which way to the future? SUBMISSIONS All manuscrip~ , drawings and photographs Filmmaker Bob Verrall, a now retired 40-year employee of the NFB, makes an impassioned plea for renewed commitment to the Film Board. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Drawer Inventory Combined G

Class Size code File # Item # Title Author CB13 half 26 #12 Population Xiao Hangha CB13 half 26 #13 Health CB13 half 26 #14 Land Xiao Kanghai Great Historical Documents - Victory Propaganda of the Great Shanghai full 26 Proletarian Culture Revolution People's Press Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #1 Animal Farm Theater Claire Coulter in "The Fever" by Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #2 Wallace Shawn Theater Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #3 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #4 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Sunbuilders in Association with Brilliant Turquoise of her A. Small Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #5 Peacocks Co. FC177 letter 020C1 #6 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 letter 020C1 #7 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 quarter 020C1 #8 Kingston Fringe Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #9 Kingston Fringe Festival Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #10 No More Medea Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #11 Walk FC177 quarter 020C1 #12 Cold Comfort FC177 quarter 020C1 #13 Cold Comfort Pagnello Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #14 Don't Forget to Breathe Group Mirimax FC177 letter 020C1 #15 Face Productions FC177 letter 020C1 #16 Newsweek. Art or Obscenity? Month of Sundays, Broadway Bound, A Night at the Grand, Baby Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #17 Sex and Politics Theatre Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #18 Shaking Like a Leaf FC177 quarter 020C1 #19 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #20 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #21 Kennedy's Children FC177 quarter 020C1 #22 Dumbwaiter/Suppress FC177 letter 020C1 #23 Bath Haydon Theatre Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #24 Using Festival West of Eden FC177 quarter 020C1 #25 Big Girls Don't Cry Production Two One Act Plays: "Winners" A. -

Official Brochure Schedule of Events

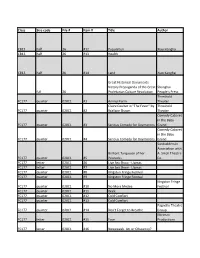

OFFICIAL BROCHURE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS July 24, 2009 - Various Locations (Tour guide: Dan Matthews) 8:30 AM - Meet in the parking lot at Black Creek Pioneer Village (will be leaving at 9:00 AM) 10:15 AM - Tour of RTA & Anne 4 Stunt Bridge, near Leaskdale 11:00 AM - Tour of L. M. Montgomery’s house, Leaskdale 11:30 AM - Tour of Pine Grove Church, Uxbridge 12:05 PM - Tour of Junior Ranger Camp 12:30 PM - Lunch break in Uxbridge 1:45 PM - Tour of MacDougal House (King Farm) 3:15 PM - Tour of Anne’s “Kissing Bridge”; Emmanuel International, Stoufville 3:45 PM - Tour of Diana Barry’s house/Avonlea manse; Bruce’s Mill Conservation, Stoufville 5:00 PM - Return to Black Creek Pioneer Village; end of day A bus will be provided by Sullivan Entertainment for attendees; yet, there will still be a few cars coming along. Also note that filming site tour venues are subject to change. July 25, 2009 - Black Creek Pioneer Village 9:30 AM - Doors open 10:00 AM - Guest Speaker: James O’Regan 12:00 PM - Lunch break 1:00 PM - Guest Speakers: Mag Ruffman / John Welsman 3:30 PM - Guest Speakers: Ian D. Clark / Michael Mahonen 5:30 PM - End of day July 26, 2009 - Black Creek Pioneer Village 9:30 AM - Doors open 10:00 AM - TO BE ANNOUNCED 12:00 PM - Lunch break 1:00 PM - TO BE ANNOUNCED 2:30 PM - Auction benefitting The Good Shepherd 4:00 PM - Guest Speaker: Marilyn Lightstone 5:30 PM - End of AvCon 2009 Please be sure to have money for lunch for all three days. -

Accounting for Adult ADHD Through the Reconstruction of Childhood

Remembering Turbulent Times: Accounting for Adult ADHD through the reconstruction of childhood Claude Jousselin Department of Anthropology, Goldsmiths, University of London A thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in social anthropology. GOLDSMITHS, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON January 2016 P a g e | 2 I, Claude Jousselin, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. P a g e | 3 Acknowledgements ADHD remains contested, controversial and is not easily disclosed due to the risk of stigmatisation; my first thank you is therefore to the support group members and their facilitators who allowed me to attend their meetings month after month, and who responded to me with curiosity and unfailing generosity. In particular I am grateful to Susan Dunn Morua from AADD-UK who supported my research proposal early on in the process and to Andrea Bilbow from ADDISS who gave me the opportunities to participate in their conferences. Similarly I want to thank the staff and patients of the specialist clinic I attended for allowing my presence in their office and observing their assessments as well as for enduring my naïve questions. My gratitude extends to the members of UKAAN and its President Phillipe Asherson, for supporting this research project and making it possible for me to gain access to scientific training courses and conferences. I want to thank Utpaul Bose for sharing his insightful understanding and passion early on in my project.