How the Philippines Turned Lessons Learned from Super Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) Into Best Practices for Disaster Preparedness and Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SBC) the Jesuit Protocol for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management

Jesuit Conference Asia Pacific-Reconciliation with Creation Scholastics and Brothers Circle {SBC) The Jesuit Protocol for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management ESSC 9ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE FOR SOCIAL CHANGE, INC CONTENTS I. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT I II II. THE JCAP DRR PROTOCOL I II II. ELEMENTS OF DISASTER RISK I II IV. SITE VISIT DESCRIPTIONS I II V. PROGRAM SCHEDULE I II VI. LIST OF PARTICIPANTS I II LISTOF MAPS MAP 1 Sites to Be Visited TY Yolanda Affected Areas II MAP 2 Riverine Flood Risk in Batug, Du lag, Leyte I II MAP 3 Hazards Daguitan Watershed I II MAP 4 Yolanda lnfographic I II MAP 5 Debris Flood in Anonang,Burauen, Leyte I II MAP 6 Flood Hazard, Brgy. Capiz & Dapdap. Alangalang. Leyte I II I. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT The Scholastics and Brothers Circle (SBC) under the Jesuit Conference Asia Pacific (JCAP) gathers annually and for 2015, disaster risk reduction (ORR) and management was selected as its work theme. In recent years, many countries and communities in Asia Pacific suffered immensely from the impacts of natural hazards-turned-disasters as the usual response systems proved to be ineffective for the scale and intensity of these events. The Asian tsunami in 2004, Cyclone Nargis and the flooding in Myanmar in 2008, Typhoon Ondoy (Ketsana) that triggered floods in the Philippines in 2009, painfully reflect the increasing frequency of extreme weather events in the region. In 2011, an earthquake struck New Zealand, Australia and Bangkok were flooded, and Japan was hit by an earthquake and tsunami that left the country at the brink of a nuclear disaster. -

How HERO Did It

How HERO did it. Now it can be told. HERO is the Ham Emergency Radio Operations formally launched upon the unveiling of the logo design contest winner during the 82nd Anniversary of the Philippine Amateur Radio Association (PARA) Inc. – the Philippine national association for the amateur radio service. Preparations HERO was activated on December 4, 2015 when it became imminent that typhoon Hagupit (local name Ruby) will make landfall somewhere in the Visayas region. It was to be a live test for HERO with Super Typhoon Yolanda in mind. Upon its activation, a lot of traffic was devoted to trying to muster hams on the 40-meter band (the PARA center of frequency on 40 meter is at 7.095 MHz). Members were advised to start building up on their redundant power supplies such as generators, solar panels, batteries and other imaginable means available as power sources. Owing to the large swathe of typhoon Ruby, it was expected to be almost like Haiyan/Yolanda. There were striking similarities. Initially, Districts 4, 5 and 9 as well as Districts 6, 7 and 8 were alerted. Both Ruby and Yolanda came from the lower quadrant of the typhoon belt. Both were packing winds more than 200 kph near the center. Both had huge footprint or diameter, with Ruby estimated to be around 600 kilometers. Both were expected to generate 3 to 6 meters storm surges and were definitely considered dangerous to lives and properties. Government was not leaving anything to chance and there were plans to forcibly evacuate people along the typhoon track especially those in the coastal area. -

Typhoon Hagupit (Ruby), Dec

Typhoon Hagupit (Ruby), Dec. 9, 2014 CDIR No. 6 BLUF – Implications to PACOM No DOD requirements anticipated PACOM Joint Liaison Group re-deploying from Philippines within next 72 hours (PACOM J35) Typhoon Hagupit – Stats & Facts Summary: (The following times in this report are Phil. local time unless otherwise specified) Current Status: Typhoon Hagupit has weakened into a tropical depression as it heads west into the West Philippine Sea towards Vietnam. All public storm warning signals have been lifted. Storm expected to head out of the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) Thursday (11 DEC) early AM. Est. rainfall is 5 – 15 mm per hour (Moderate – heavy) within the 200 km of the storm. (NDRRMC, Bulletin No. 23) Local officials reported nearly 13,000 houses were destroyed and more than 22,300 were partially damaged in Eastern Samar province, where Hagupit first hit as a CAT 3 typhoon on 6 DEC. (Reuters) Deputy Presidential Spokesperson Key Concerns & Trends Abigail Valte said so far, Dolores appears worst hit. (GPH) Domestic air and sea travel has resumed, markets reopened • GPH and the international humanitarian community are and state workers returned to their offices. Some shopping capable of meeting virtually all disaster response requirements. Major malls were open but schools remained closed. actions and activities include: The privately run National Grid Corp said nearly two million Assessments are ongoing to determine the full extent of the homes across central Philippines and southern Luzon remain typhoon’s impact; reports so far indicate the scale and severity without power. (Reuters) Twenty provinces in six regions of the impact of Hagupit was not as great as initially feared. -

9065C70cfd3177958525777b

The FY 1989 Annual Report of the Agency for international DevelaprnentiOHiee of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance was researched. written, and produced by Cynthia Davis, Franca Brilliant, Mario Carnilien, Faye Henderson, Waveriy Jackson, Dennis J. King, Wesley Mossburg, Joseph OYConnor.Kimberly S.C. Vasconez. and Beverly Youmans of tabai Anderson Incorparated. Arlingtot?. Virginia, under contract ntrmber QDC-0800-C-00-8753-00, Office 0%US Agency ior Foreign Disaster Enternatiorr~ai Assistance Development Message from the Director ............................................................................................................................. 6 Summary of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance .............................................................................................. 8 Retrospective Look at OFDA's 25 Years of Operations ................................................................................. 10 OFDA Emergency Response ......................................................................................................................... 15 Prior-Year (FY 1987 and 1988) and Non-Declared Disasters FV 1989 DISASTERS LUROPE Ethiopia Epidemic ................................. ............. 83 Soviet Union Accident ......................................... 20 Gabon Floods .................................... ... .................84 Soviet Union Earthquake .......................................24 Ghana Floods ....................................................... 85 Guinea Bissau Fire ............................................. -

Report on UN ESCAP / WMO Typhoon Committee Members Disaster Management System

Report on UN ESCAP / WMO Typhoon Committee Members Disaster Management System UNITED NATIONS Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific January 2009 Disaster Management ˆ ` 2009.1.29 4:39 PM ˘ ` 1 ¿ ‚fiˆ •´ lp125 1200DPI 133LPI Report on UN ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee Members Disaster Management System By National Institute for Disaster Prevention (NIDP) January 2009, 154 pages Author : Dr. Waonho Yi Dr. Tae Sung Cheong Mr. Kyeonghyeok Jin Ms. Genevieve C. Miller Disaster Management ˆ ` 2009.1.29 4:39 PM ˘ ` 2 ¿ ‚fiˆ •´ lp125 1200DPI 133LPI WMO/TD-No. 1476 World Meteorological Organization, 2009 ISBN 978-89-90564-89-4 93530 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspon- dence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chairperson, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box No. 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] NOTE The designations employed in WMO publications and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of WMO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Typhoon Hagupit – Situation Report (20:30 Manila Time)

TYPHOON HAGUPIT NR. 1 7 DECEMBER 2014 Typhoon Hagupit – Situation Report (20:30 Manila Time) GENERAL INFORMATION - Typhoon Hagupit made landfall on Saturday 6 December at 9:15 pm in Dolores, Eastern Samar. After weakening to a Category 2 typhoon, Hagupit then made a second landfall in Cataingan, Masbate on Sunday 7 December. - Typhoon Hagupit has maintained its strength and is now (8:00 pm Manila Time) over the vicinity of Aroroy, Masbate. According to PAGASA’s weather bulletin issued today, 7 December at 18:00, the expected third landfall over Sibuyan Island will be between 02:00 – 04:00 in the morning tomorrow and will be associated with strong winds, storm surge and heavy to torrential rainfall. Hagupit is expected to exit the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) on Thursday morning. - The typhoon is not as powerful as Typhoon Haiyan but Hagupit is moving slowly through the Philippines meaning prolonged rainfall and an increased likelihood of flooding and landslides. Currently the extent of damage is not yet clear. The authorities will send an assessment mission tomorrow to Region VIII where some municipalities in Eastern and Northern Samar are thought to have sustained heavier damage. Signal no. 1 has been issued in Manila, down from Signal no. 2 this morning Forecast Positions: - 24 hour (tomorrow afternoon): 60 km East of Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro or at 160 km South of Science Garden, Quezon City. - 48 hour (Tuesday afternoon): 170 km Southwest of Science Garden, Quezon City. - 72 hour (Wednesday afternoon): 400 km West of Science Garden, Quezon City. TYPHOON HAGUPIT NR. -

Sheared Deep Vortical Convection in Pre‐Depression Hagupit During TCS08 Michael M

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 37, L06802, doi:10.1029/2009GL042313, 2010 Click Here for Full Article Sheared deep vortical convection in pre‐depression Hagupit during TCS08 Michael M. Bell1,2 and Michael T. Montgomery1,3 Received 28 December 2009; accepted 4 February 2010; published 17 March 2010. [1] Airborne Doppler radar observations from the recent (2008) that occurred during the TCS08 experiment, and Tropical Cyclone Structure 2008 field campaign in the suggested that the pre‐Nuri disturbance was of the easterly western North Pacific reveal the presence of deep, buoyant wave type with the preferred location for storm genesis near and vortical convective features within a vertically‐sheared, the center of the cat’s eye recirculation region that was readily westward‐moving pre‐depression disturbance that later apparent in the frame of reference moving with the wave developed into Typhoon Hagupit. On two consecutive disturbance. This work suggests that this new cyclogenesis days, the observations document tilted, vertically coherent model is applicable in easterly flow regimes and can prove precipitation, vorticity, and updraft structures in response to useful for tropical weather forecasting in the WPAC. It the complex shearing flows impinging on and occurring reaffirms also that easterly waves or other westward propa- within the disturbance near 18 north latitude. The observations gating disturbances are often important ingredients in the and analyses herein suggest that the low‐level circulation of formation process of typhoons [Chang, 1970; Reed and the pre‐depression disturbance was enhanced by the coupling Recker, 1971; Ritchie and Holland, 1999]. Although the of the low‐level vorticity and convergence in these deep Nuri study offers compelling support for the large‐scale convective structures on the meso‐gamma scale, consistent ingredients of this new tropical cyclogenesis model [Dunkerton with recent idealized studies using cloud‐representing et al., 2009], it leaves open important unanswered questions numerical weather prediction models. -

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

This is OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 1 COORDINATION SAVES LIVES OCHA mobilizes humanitarian assistance for all people in need OCHA helps prepare for the next crisis To reduce the impact of natural and man-made disasters on people, OCHA works with Governments to strengthen their capacity to handle emergencies. OCHA assists UN Member States with early warning information, vulnerability analysis, contingency planning and national capacity-building and training, and by mobilizing support from regional networks. Cover photo: OCHA/May Munoz This page: OCHA/Jose Reyna OCHA delivers its mandate through… COORDINATION OCHA brings together people, tools and experience to save lives OCHA helps Governments access tools and services that provide life-saving relief. We deploy rapid-response teams, and we work with partners to assess needs, take action, secure funds, produce reports and facilitate civil-military coordination. ADVOCACY ! OCHA speaks on behalf of people affected by conflict and disaster ? ! Using a range of channels and platforms, OCHA speaks out publicly when necessary. We work behind the scenes, negotiating on issues such as access, humanitarian principles, and protection of civilians and aid workers, to ensure aid is where it needs to be. INFORMATION MANAGEMENT ? OCHA collects, analyses and shares critical information OCHA gathers and shares reliable data on where crisis-affected people are, what they urgently need and who is best placed to assist them. Information products support swift decision-making and planning. HUMANITARIAN FINANCING OCHA organizes and monitors humanitarian funding OCHA’s financial-tracking tools and services help manage humanitarian donations from more than 130 countries. -

Typhoon Hagupit (Ruby), Dec

Typhoon Hagupit (Ruby), Dec. 6, 2014 BLUF – Implications to PACOM No disaster declaration or request for US Govt. support has been made yet. DOD capabilities most likely to be requested include: o Medium to heavy helicopter lift support o Fixed wing lift support o Surface and Airborne Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) o Transportation and logistics support o ISR Support o Debris clearing at airports and ports o Logistics support Typhoon Hagupit – Stats & Facts o Water purification Summary: Typhoon Hagupit (locally known as Ruby), o Generators made landfall on Saturday evening (December 6, o Assessment support Philippine time) in the vicinity of Dolores in Eastern o Information dissemination platforms Samar and was heading towards Masbate with o Communications in affected areas reported max. sustained winds of 175 kph near the o Fuel center and gusts up to 210 kph. As of the writing of this report (1300 HST), Hagupit has slightly weakened and is now in the vicinity of Catbalogan City, Samar. The Philippines meteorological agency PAGASA forecasts the storm to move West- Northwest at 15 kph. (NDRRMC) Key Concerns & Trends Hagupit will make an expected second landfall on Sunday afternoon (December 7, Philippine time) in the vicinity of Masbate with strong winds, heavy to • A total of 132,351 families/656,082 people torrential rainfall and storm surge up to 4.5 meters. conducted pre-emptive evacuation in Regions IV-A, V, VII, (PAGASA) VIII and CARAGA. (NDRRMC) • Estimated rainfall within the 600 km diameter of Hagupit is expected to exit the Philippine Area of Responsibility on Wednesday evening (December 10 the storm is from 10 – 30 mm per hour (heavy to Philippine time). -

UAP Post Issue, Corazon F

VOLUME 40 • OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2014 2 Editorial, National Board of Directors, About the Cover 3 National President’s Page 5 Executive Commissions 4 Secretary General 6 Around Area A 8 Around Area B 12 World Day of Architecture 2014 Events 14 National Architecture Week 2014 Events 15 NAW 2014 Summarized Report 16 WDA 2014 Celebration 18 Around Area C 22 Around Area D 26 ArQuaTecture Aspirations Toward a Dignified Living 27 Past UAP National President takes oath as New PRC Commissioner 28 UAPSA ConFab Quadripartite 30 BAYANIHANG ARKITEKTURA: a UAP Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative editorial board The United Architects of the is?” The architects play very important role in the Philippines celebrated the World urban development and the well-being of its local Day of Architecture 2014. This inhabitants. In our own little ways, we can achieve year, WDA was celebrated on in making our cities liveable as architects are problem EDITORIAL October 6, 2014. Initiated by the solvers and earth keepers. UIA or the Union Internationale des In closing, let me quote from Alain De Botton, COUNCIL Architectes, annually it is celebrated the author of the book Architecture of Happiness, FY 2014-2015 every first Monday of October. This “We owe it to the fields that our houses will not be year’s theme “Healthy Cities, Happy the inferiors of the virgin land they have replaced. We Cities” is very relevant to our very own cities which owe it to the worms and the trees that the building we are full of so many challenges. The theme also want fuap, NP cover them with will stand as promises of the highest Ma. -

Hong Kong Observatory, 134A Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong

78 BAVI AUG : ,- HAISHEN JANGMI SEP AUG 6 KUJIRA MAYSAK SEP SEP HAGUPIT AUG DOLPHIN SEP /1 CHAN-HOM OCT TD.. MEKKHALA AUG TD.. AUG AUG ATSANI Hong Kong HIGOS NOV AUG DOLPHIN() 2012 SEP : 78 HAISHEN() 2010 NURI ,- /1 BAVI() 2008 SEP JUN JANGMI CHAN-HOM() 2014 NANGKA HIGOS(2007) VONGFONG AUG ()2005 OCT OCT AUG MAY HAGUPIT() 2004 + AUG SINLAKU AUG AUG TD.. JUL MEKKHALA VAMCO ()2006 6 NOV MAYSAK() 2009 AUG * + NANGKA() 2016 AUG TD.. KUJIRA() 2013 SAUDEL SINLAKU() 2003 OCT JUL 45 SEP NOUL OCT JUL GONI() 2019 SEP NURI(2002) ;< OCT JUN MOLAVE * OCT LINFA SAUDEL(2017) OCT 45 LINFA() 2015 OCT GONI OCT ;< NOV MOLAVE(2018) ETAU OCT NOV NOUL(2011) ETAU() 2021 SEP NOV VAMCO() 2022 ATSANI() 2020 NOV OCT KROVANH(2023) DEC KROVANH DEC VONGFONG(2001) MAY 二零二零年 熱帶氣旋 TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 2020 2 二零二一年七月出版 Published July 2021 香港天文台編製 香港九龍彌敦道134A Prepared by: Hong Kong Observatory, 134A Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong © 版權所有。未經香港天文台台長同意,不得翻印本刊物任何部分內容。 © Copyright reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the Director of the Hong Kong Observatory. 知識產權公告 Intellectual Property Rights Notice All contents contained in this publication, 本刊物的所有內容,包括但不限於所有 including but not limited to all data, maps, 資料、地圖、文本、圖像、圖畫、圖片、 text, graphics, drawings, diagrams, 照片、影像,以及數據或其他資料的匯編 photographs, videos and compilation of data or other materials (the “Materials”) are (下稱「資料」),均受知識產權保護。資 subject to the intellectual property rights 料的知識產權由香港特別行政區政府 which are either owned by the Government of (下稱「政府」)擁有,或經資料的知識產 the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (the “Government”) or have been licensed to 權擁有人授予政府,為本刊物預期的所 the Government by the intellectual property 有目的而處理該等資料。任何人如欲使 rights’ owner(s) of the Materials to deal with 用資料用作非商業用途,均須遵守《香港 such Materials for all the purposes contemplated in this publication. -

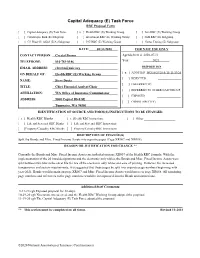

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form [ ] Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force [ x ] Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Life RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Catastrophe Risk (E) Subgroup [ ] Investment RBC (E) Working Group [ ] SMI RBC (E) Subgroup [ ] C3 Phase II/ AG43 (E/A) Subgroup [ ] P/C RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Stress Testing (E) Subgroup DATE: 08/31/2020 FOR NAIC USE ONLY CONTACT PERSON: Crystal Brown Agenda Item # 2020-07-H TELEPHONE: 816-783-8146 Year 2021 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] DISPOSITION [ x ] ADOPTED WG 10/29/20 & TF 11/19/20 ON BEHALF OF: Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] REJECTED NAME: Steve Drutz [ ] DEFERRED TO TITLE: Chief Financial Analyst/Chair [ ] REFERRED TO OTHER NAIC GROUP AFFILIATION: WA Office of Insurance Commissioner [ ] EXPOSED ________________ ADDRESS: 5000 Capitol Blvd SE [ ] OTHER (SPECIFY) Tumwater, WA 98501 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCE AND FORM(S)/INSTRUCTIONS TO BE CHANGED [ x ] Health RBC Blanks [ x ] Health RBC Instructions [ ] Other ___________________ [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Blanks [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Instructions [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Blanks [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Instructions DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE(S) Split the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets into separate pages (Page XR007 and XR008). REASON OR JUSTIFICATION FOR CHANGE ** Currently the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets are included on page XR007 of the Health RBC formula. With the implementation of the 20 bond designations and the electronic only tables, the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets were split between two tabs in the excel file for use of the electronic only tables and ease of printing. However, for increased transparency and system requirements, it is suggested that these pages be split into separate page numbers beginning with year-2021.