A Performer's Guide and Structural Analysis of Sergei Taneyev's Concert Suite for Violin and Orchestra by Aihua Zhang a Rese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

(1; . -;-."':::With, Say, Itzhak ~ ...•

PROKOFIEVViolin concertos nO.1 in D major op.19 & no.2 . in G minor op.63. Sonata in C major for two violins op.56* [ Pavel Berman, Anna find the effect here, especially Tifu* (violin) Orchestra in the Second Concerto, I della Svizzera ltaliana/ initially disorientating. Yet Andrey Boreyko to hear Prokofiev's super- DYNAMIC CD5 676 virtuoso writing emerging Indianapo!is prizewinner wìth such blernishless poìse Pavel Berman brings and unforced eloquence comes freshness and eloquence as a welcome relìef compared to Prokofiev to the claustrophobic intensity of most recorded accounts. When cornpared The Double Violin Sonata is .(1; . -;-."':::with, say, Itzhak also beautìfully played and . ~~~i,-""-.=...• Perlman's EMI record ed, with Prokofiev's - ' recording wìth lyrìcal genius well to the fore, ~ Gennadi JULlAN HAYLOCK Rozhdestvensky or Isaac Stern's Sony classìc with Eugene Orrnandy, the natural perspectives of this new version, where Pavel Berrnan's sweer-toned playing emerges seductively frorn the orchestrai ranks, are such that one couId almost be listening to different pieces. Subtle internai orchestrai detaìl is revealed (particularly in the First Concerto) that usuali)' lies concealed behind the solo image. The passages where Bcrrnan duets engagingl), with solo woodwind instrumenrs or harp feel more 'sinfonia concertante' than concerto proper. The effect, especially rowards the end of the finale, is often magical, as Berman's silvery purity becomes enveloped in a pulsating web of orchestrai sound. Those raised on classi c accounts from David Oistrakh (EMI),Kyung-Wha Chung (Dccca) or Shlorno Mintz (Deutsche Grammophon), in which one can hear and feel the contract ofbow on string or fingers on fingerboard, ma)' AUGUST 2011 THE STRAD 93 Rue St-Pierre 2 - 1003 Lausanne (eH) Te1. -

Focus on Marie Samuelsson Armas Järnefelt

HIGHLIGHTS NORDIC 4/2018 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Focus on Marie Samuelsson Armas Järnefelt – an all-round Romantic NEWS Joonas Kokkonen centenary 2021 Mats Larsson Gothe awarded Th e major Christ Johnson Prize has been awarded to Th e year 2021 will mark the centenary of the Mats Larsson Gothe for his …de Blanche et Marie…– Jesper Lindgren Photo: birth of Joonas Kokkonen. More and more Symphony No. 3. Th e jury’s motivation is as follows: music by him has been fi nding its way back into ”With a personal musical language, an unerring feeling concert programmes in the past few years, and for form, brilliant orchestration and an impressive craft his opera Viimeiset kiusaukset (Th e Last Temp- of composition, Larsson Gothe passes on with a sure tations) is still one of the Finnish operas hand the great symphonic tradition of our time.” Th e most often performed. Fennica Gehrman has symphony is based on motifs from his acclaimed published a new version of the impressive Requi- opera Blanche and Marie and was premiered by em he composed in 1981 in memory of his wife. the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic during their Th e arrangement by Jouko Linjama is for organ, Composer Weekend Festival 2016. mixed choir and soloists. Th e Cello Concerto has also found an established place in the rep- ertoire; it was heard most recently in the Finals Söderqvist at the Nobel Prize of the International Paulo Cello Competition in Concert October 2018. Ann-Sofi Söder- Photo: Maarit Kytöharju Photo: qvist’s Movements Photo: Pelle Piano Pelle Photo: opens this year’s Finland Vuorjoki/Music Saara Photo: Nobel Prize Con- cert in Stockholm on 9 December. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Download Booklet

557757 bk Bloch US 20/8/07 8:50 pm Page 5 Royal Scottish National Orchestra the Sydney Opera, has been shown over fifty times on U.S. television, and has been released on DVD. Serebrier regularly champions contemporary music, having commissioned the String Quartet No. 4 by Elliot Carter (for his Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, and subsequently known as the Scottish National Orchestra before being Festival Miami), and conducted world première performances of music by Rorem, Schuman, Ives, Knudsen, Biser, granted the title Royal at its centenary celebrations in 1991, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is one of Europe’s and many others. As a composer, Serebrier has won most important awards in the United States, including two leading ensembles. Distinguished conductors who have contributed to the success of the orchestra include Sir John Guggenheims (as the youngest in that Foundation’s history, at the age of nineteen), Rockefeller Foundation grants, Barbirolli, Karl Rankl, Hans Swarowsky, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Bryden Thomson, Neeme Järvi, commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Harvard Musical Association, the B.M.I. Award, now Conductor Laureate, and Walter Weller who is now Conductor Emeritus. Alexander Lazarev, who served as Koussevitzky Foundation Award, among others. Born in Uruguay of Russian and Polish parents, Serebrier has Ernest Principal Conductor from 1997 to 2005, was recently appointed Conductor Emeritus. Stéphane Denève was composed more than a hundred works. His First Symphony had its première under Leopold Stokowski (who gave appointed Music Director in 2005 and his first recording with the RSNO of Albert Roussel’s Symphony No. -

Limited Edition 150 Th Anniversary of the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory

Limited Edition 150 th Anniversary of the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory This production is made possible by the sponsorship of BP Это издание стало возможным благодаря спонсорской помощи компании BP Richter Live in Moscow Conservatory 1951 – 1965 20 VOLUMES (27 CDs) INCLUDES PREVIOUSLY UNRELEASED RECORDINGS VOLUME 1 0184/0034 A D D MONO TT: 62.58 VOLUME 2 0184/0037A A D D MONO TT: 59.18 Sergey Rachmaninov (1873 – 1943) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) Twelve Preludes: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, op. 15 1 No. 2 in F sharp minor, op. 23 No. 1 3.43 1 1. Allegro con brio 16.40 2 No. 20 in A major, op. 32 No. 9 2.25 2 2. Largo 11.32 3 No. 21 in B minor, op. 32 No. 10 5.15 3 3. Rondo. Allegro scherzando 8.50 4 No. 23 in G sharp minor, op. 32 No. 12 2.10 Sergey Prokofiev (1891 – 1953) 5 No. 9 in A flat major, op. 23 No. 8 2.54 Piano Concerto No. 5 in G major, op. 55 6 No. 18 in F major, op. 32 No. 7 2.03 4 1. Allegro con brio 5.07 7 No. 12 in C major, op. 32 No. 1 1.12 5 2. Moderato ben accentuato 3.54 8 No. 13 in B flat minor, op. 32 No. 2 3.08 6 3. Toccata. Allegro con fuoco 1.52 9 No. 3 in B flat major, op. 23 No. 2 3.13 7 4. Larghetto 6.05 10 No. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

EDGAR MOREAU, Cellist

EDGAR MOREAU, cellist “Mr. Moreau immediately began to display his musical flair and his distinctive persona. His incredibly beautiful tone spoke directly to the heart and soul. Mr. Moreau established his credentials as a player of remarkable caliber. His intriguing presence, marvelously messy hair, and expressive face were all reflections of the inner poet.” —OBERON’S GROVE (NY) “This cello prodigy belongs in the family of the greatest artists of all time. The audience gave him an enthusiastic ovation in recognition of a divinely magical evening.” —LA PROVENCE ”He is just 20 years old, but for the past five years, this young musketeer of the bow has been captivating all of his audiences. He is the rising star of the French cello.” —LE FIGARO “Edgar Moreau captivates all those who hear him. Behind his boyish looks lies a performer of rare maturity. He is equally at ease in a chamber ensemble, as a soloist with orchestra or in recital, and his facility and pose are simply astounding.” —DIAPASON (Debut CD: “Play” ) European Concert Hall Organization’s 2016-2017 Rising Star 2015 Arthur Waser Foundation Award, in association with the Lucerne Symphony (Switzerland) 2015 Solo Instrumentalist of the Year, Victoires de la Musique Tchaikovsky Competition, 2011, Second Prize and Prize for Best Performance of the Commissioned Work First Prize, 2014 Young Concert Artists International Auditions Florence Gould Foundation Fellowship The Embassy Series Prize (Washington, DC) • The Friends of Music Concerts Prize (NY) The Harriman-Jewell Series Prize (MO) • The Saint Vincent College Concert Series Prize (PA) Chamber Orchestra of the Triangle Prize (NC) • University of Florida Performing Arts Prize The Candlelight Concert Society Prize (MD) YOUNG CONCERT ARTISTS, INC. -

MUSICAL CENSORSHIP and REPRESSION in the UNION of SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ

SAYI 17 BAHAR 2018 MUSICAL CENSORSHIP AND REPRESSION IN THE UNION OF SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ Abstract In the beginning of 1930s, institutions like Association for Contemporary Music and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians were closed down with the aim of gathering every study of music under one center, and under the control of the Communist Party. As a result, all the studies were realized within the two organizations of the Composers’ Union in Moscow and Leningrad in 1932, which later merged to form the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948. In 1948, composer Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) was appointed as the frst president of the Union of Soviet Composers by Andrei Zhdanov and continued this post until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Being one of the most controversial fgures in the history of Soviet music, Khrennikov became the third authority after Stalin and Zhdanov in deciding whether a composer or an artwork should be censored or supported by the state. Khrennikov’s main job was to ensure the application of socialist realism, the only accepted doctrine by the state, on the feld of music, and to eliminate all composers and works that fell out of this context. According to the doctrine of socialist realism, music should formalize the Soviet nationalist values and serve the ideals of the Communist Party. Soviet composers should write works with folk music elements which would easily be appreciated by the public, prefer classical orchestration, and avoid atonality, complex rhythmic and harmonic structures. In this period, composers, performers or works that lacked socialist realist values were regarded as formalist. -

2013-2014 Master Class-Ilya Kaler (Violin)

Master Class with Ilya Kaler Sunday, October 13, 2013 at 6:00 p.m. Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Boca Raton, Florida Program Concerto No. 3 in B Minor Camille Saint-Saens Allegro non troppo (1835-1921) Mozhu Yan, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Concerto No. 3 in B Minor Camille Saint-Saens Andantino quasi allegretto (1835-1921) Julia Jakkel, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano INTERMISSION Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46 Max Bruch Adagio cantabile (1838-1920) Anna Tsukervanik, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Violin Concerto No. 1 Niccolo Paganini Allegro maestoso – Tempo giusto (1782-1840) Yordan Tenev, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano ILYA KALER Described by London’s Gramophone as a ‘magician, bewitching our ears’, Ilya Kaler is one of the most outstanding personalities of the violin today. Among his many awards include 1st Prizes and Gold Medals at the Tchaikovsky (1986), the Sibelius (1985) and the Paganini (1981) Competitions. Ilya Kaler was born in Moscow, Russia into a family of musicians. Major teachers at the Moscow Central Music School and the Moscow Conservatory included Zinaida Gilels, Leonid Kogan, Victor Tretyakov and Abram Shtern. Mr Kaler has earned rave reviews for solo appearances with distinguished orchestras throughout the world, which included the Leningrad, Moscow and Dresden Philharmonic Orchestras, the Montreal Symphony, the Danish and Berlin Radio Orchestras, Detroit Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Seattle Symphony, New Japan Philharmonic, the Moscow and Zurich Chamber Orchestras, among others. His solo recitals have taken him throughout the former Soviet Union, the United States, East Asia, Europe, Latin America, South Africa and Israel. -

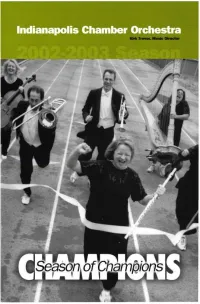

Iseason of Cham/Dions

Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra Kirk Trevor, Music Director ISeason of Cham/Dions <s a sizzling performance San Francisco Examiner October 14, 2002 February 23, 2003 7:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Ilya Kaler, violin Gabriela Demeterova, violin November 4, 2002 March 24, 2003 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. Paul Barnes, piano Larry Shapiro, violin Marjorie Lange Hanna, cello Csaba Erdelyi, viola December 15, 2002 April 13, 2003 2:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Bach's Christmas Handel's Messiah Oratorio with with Indianapolis Indianapolis Symphonic Choir Symphonic Choir and Eric Stark January 27, 2003 May 12, 2003 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. Christopher Layer, Olga Kern, piano bagpipes simply breath-taking Howard Aibel. New York Concert Review All eight concerts will be performed at Clowes Memorial Hall of Butler University. Tickets are $20 and available at the Clowes Hall box office, Ticket CHAMBER Central and all Ticketmaster ticket ORCHESTRA centers or charge by phone at Kirk Trevor, Music Director 317.239.1000. www.icomusic.org Special Thanks CG>, r:/ /GENERA) L HOTELS CORPORATION For providing hotel accommodations for Maestro Trevor and the ICO guest artists Wiu 103.7> 951k \%ljm 100.7> 2002-2003 Season Media Partner With the support of the ARTSKElNDIANA % d ARTS COUNCIt OF INDIANAPOLIS * ^^[>4foyJ and Cily o( Indianapolis INDIANA ARTS COMMISSJON l<IHWI|>l|l»IMIIW •!••. For their continued support of the arts Shopping for that hard-to-buy-for friend relative spouse co-worker? Try an ICO 3-pak Specially wrapped holiday 3-paks are available! Visit the table in the lobby tonight or call the ICO office at 317.940.9607 The music performed in the lobby at tonight's performance was provided by students from Lawrence Central High School Thank you for sharing your musical talent with us! Complete this survey for a chance to win 2 tickets to the 2003-2004 Clowes Performing Arts Series.