Chapter 7:The Quantum-Mechanical Model of the Atom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Balmer Series

The Balmer Series Introduction Historically, the spectral lines of hydrogen have been categorized as six distinct series. The visible portion of the hydrogen spectrum is contained in the Balmer series, named after Johann Balmer who discovered an empirical relationship for calculating its wave- lengths [2]. In 1885 Balmer discovered that by labeling the four visible lines of the hydorgen spectrum with integers n, (n = 3, 4, 5, 6) (See Table 1 and Figure 1) each wavelength λ could be calculated from the relationship n2 λ = B , (1) n2 − 4 where B = 364.56 nm. Johannes Rydberg generalized Balmer’s result to include all of the wavelengths of the hydrogen spectrum. The Balmer formula is more commonly re–expressed in the form of the Rydberg formula 1 1 1 = RH − , (2) λ 22 n2 where n =3, 4, 5 . and the Rydberg constant RH =4/B. The purpose of this experiment is to determine the wavelengths of the visible spec- tral lines of hydrogen using a spectrometer and to calculate the Balmer constant B. Procedure The spectrometer used in this experiment is shown in Fig. 1. Adjust the diffraction grating so that the normal to its plane makes a small angle α to the incident beam of light. This is shown schematically in Fig. 2. Since α u 0, the angles between the first and zeroth order intensity maxima on either side, θ and θ0 respectively, are related to the wavelength λ of the incident light according to [1] λ = d sin(φ) , (3) accurate to first order in α. Here, d is the separation between the slits of the grating, and θ0 + θ φ = (4) 2 1 Color Wavelength [nm] Integer [n] Violet2 410.2 6 Violet1 434.0 5 blue 486.1 4 red 656.3 3 Table 1: The wavelengths and integer associations of the visible spectral lines of hy- drogen shown in Fig. -

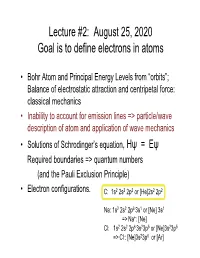

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal Is to Define Electrons in Atoms

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal is to define electrons in atoms • Bohr Atom and Principal Energy Levels from “orbits”; Balance of electrostatic attraction and centripetal force: classical mechanics • Inability to account for emission lines => particle/wave description of atom and application of wave mechanics • Solutions of Schrodinger’s equation, Hψ = Eψ Required boundaries => quantum numbers (and the Pauli Exclusion Principle) • Electron configurations. C: 1s2 2s2 2p2 or [He]2s2 2p2 Na: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1 or [Ne] 3s1 => Na+: [Ne] Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s23p5 or [Ne]3s23p5 => Cl-: [Ne]3s23p6 or [Ar] What you already know: Quantum Numbers: n, l, ml , ms n is the principal quantum number, indicates the size of the orbital, has all positive integer values of 1 to ∞(infinity) (Bohr’s discrete orbits) l (angular momentum) orbital 0s l is the angular momentum quantum number, 1p represents the shape of the orbital, has integer values of (n – 1) to 0 2d 3f ml is the magnetic quantum number, represents the spatial direction of the orbital, can have integer values of -l to 0 to l Other terms: electron configuration, noble gas configuration, valence shell ms is the spin quantum number, has little physical meaning, can have values of either +1/2 or -1/2 Pauli Exclusion principle: no two electrons can have all four of the same quantum numbers in the same atom (Every electron has a unique set.) Hund’s Rule: when electrons are placed in a set of degenerate orbitals, the ground state has as many electrons as possible in different orbitals, and with parallel spin. -

Rydberg Constant and Emission Spectra of Gases

Page 1 of 10 Rydberg constant and emission spectra of gases ONE WEIGHT RECOMMENDED READINGS 1. R. Harris. Modern Physics, 2nd Ed. (2008). Sections 4.6, 7.3, 8.9. 2. Atomic Spectra line database https://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/ASD/lines_form.html OBJECTIVE - Calibrating a prism spectrometer to convert the scale readings in wavelengths of the emission spectral lines. - Identifying an "unknown" gas by measuring its spectral lines wavelengths. - Calculating the Rydberg constant RH. - Finding a separation of spectral lines in the yellow doublet of the sodium lamp spectrum. INSTRUCTOR’S EXPECTATIONS In the lab report it is expected to find the following parts: - Brief overview of the Bohr’s theory of hydrogen atom and main restrictions on its application. - Description of the setup including its main parts and their functions. - Description of the experiment procedure. - Table with readings of the vernier scale of the spectrometer and corresponding wavelengths of spectral lines of hydrogen and helium. - Calibration line for the function “wavelength vs reading” with explanation of the fitting procedure and values of the parameters of the fit with their uncertainties. - Calculated Rydberg constant with its uncertainty. - Description of the procedure of identification of the unknown gas and statement about the gas. - Calculating resolution of the spectrometer with the yellow doublet of sodium spectrum. INTRODUCTION In this experiment, linear emission spectra of discharge tubes are studied. The discharge tube is an evacuated glass tube filled with a gas or a vapor. There are two conductors – anode and cathode - soldered in the ends of the tube and connected to a high-voltage power source outside the tube. -

Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology Aaron Hankin

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Physics & Astronomy ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-28-2015 Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology Aaron Hankin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/phyc_etds Recommended Citation Hankin, Aaron. "Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/phyc_etds/23 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics & Astronomy ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aaron Hankin Candidate Physics and Astronomy Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Ivan Deutsch , Chairperson Carlton Caves Keith Lidke Grant Biedermann Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology by Aaron Michael Hankin B.A., Physics, North Central College, 2007 M.S., Physics, Central Michigan Univeristy, 2009 DISSERATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Physics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2014 iii c 2014, Aaron Michael Hankin iv Dedication To Maiko and our unborn daughter. \There are wonders enough out there without our inventing any." { Carl Sagan v Acknowledgments The experiment detailed in this manuscript evolved rapidly from an empty lab nearly four years ago to its current state. Needless to say, this is not something a graduate student could have accomplished so quickly by him or herself. -

23-Chapt-6-Quantum2

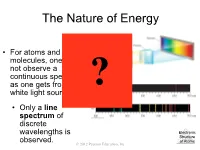

The Nature of Energy • For atoms and molecules, one does not observe a continuous spectrum, as one gets from a ? white light source. • Only a line spectrum of discrete wavelengths is Electronic Structure observed. of Atoms © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. The Players Erwin Schrodinger Werner Heisenberg Louis Victor De Broglie Neils Bohr Albert Einstein Max Planck James Clerk Maxwell Neils Bohr Explained the emission spectrum of the hydrogen atom on basis of quantization of electron energy. Neils Bohr Explained the emission spectrum of the hydrogen atom on basis of quantization of electron energy. Emission spectrum Emitted light is separated into component frequencies when passed through a prism. 397 410 434 486 656 wavelenth in nm Hydrogen, the simplest atom, produces the simplest emission spectrum. In the late 19th century a mathematical relationship was found between the visible spectral lines of hydrogen the group of hydrogen lines in the visible range is called the Balmer series 1 1 1 = R – λ ( 22 n2 ) Rydberg 1.0968 x 107m–1 Constant Johannes Rydberg Bohr Solution the electron circles nucleus in a circular orbit imposed quantum condition on electron energy only certain “orbits” allowed energy emitted is when electron moves from higher energy state (excited state) to lower energy state the lowest electron energy state is ground state ground state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 n = 2 n = 1 e- excited state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 e- n = 2 n = 1 hν excited state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 n = 2 e- n = 1 hν excited state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 e- n = 2 n = 1 hν Emission spectrum Emitted light is separated into component frequencies when passed through a prism. -

Wolfgang Pauli 1900 to 1930: His Early Physics in Jungian Perspective

Wolfgang Pauli 1900 to 1930: His Early Physics in Jungian Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota by John Richard Gustafson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Advisor: Roger H. Stuewer Minneapolis, Minnesota July 2004 i © John Richard Gustafson 2004 ii To my father and mother Rudy and Aune Gustafson iii Abstract Wolfgang Pauli's philosophy and physics were intertwined. His philosophy was a variety of Platonism, in which Pauli’s affiliation with Carl Jung formed an integral part, but Pauli’s philosophical explorations in physics appeared before he met Jung. Jung validated Pauli’s psycho-philosophical perspective. Thus, the roots of Pauli’s physics and philosophy are important in the history of modern physics. In his early physics, Pauli attempted to ground his theoretical physics in positivism. He then began instead to trust his intuitive visualizations of entities that formed an underlying reality to the sensible physical world. These visualizations included holistic kernels of mathematical-physical entities that later became for him synonymous with Jung’s mandalas. I have connected Pauli’s visualization patterns in physics during the period 1900 to 1930 to the psychological philosophy of Jung and displayed some examples of Pauli’s creativity in the development of quantum mechanics. By looking at Pauli's early physics and philosophy, we gain insight into Pauli’s contributions to quantum mechanics. His exclusion principle, his influence on Werner Heisenberg in the formulation of matrix mechanics, his emphasis on firm logical and empirical foundations, his creativity in formulating electron spinors, his neutrino hypothesis, and his dialogues with other quantum physicists, all point to Pauli being the dominant genius in the development of quantum theory. -

Wave-Particle Duality 波粒二象性

Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality 波粒二象性 Classical Physics Object Govern Laws Phenomena Particles Newton’s Law Mechanics, Heat Fields and Waves Maxwell’s Eq. Optics, Electromagnetism Our interpretation of the experimental material rests essentially upon the classical concepts ... 我们对实验资料的诠释,是本质地建筑在经典概念之上的。 — N. Bohr, 1927. SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality — Photon 电磁波 Electromagnetic wave, James Clerk Maxwell: Maxwell’s Equations, 1860; Heinrich Hertz, 1888 黑体辐射 Blackbody radiation, Max PlanckNP1918: Planck’s constant, 1900 光电效应 Photoelectric effect, Albert EinsteinNP1921: photons, 1905 All these fifty years of conscious brooding have brought me no nearer to the answer to the question, “What are light quanta?” Nowadays every Tom, Dick and Harry thinks he knows it, but he is mistaken. 这五十年来的思考,没有使我更加接近 “什么是光量子?” 这个问题的 答案。如今,每个人都以为自己知道这个答案,但其实是被误导了。 — Albert Einstein, to Michael Besso, 1954 SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality — Electron Electron in an Atom Electron: Cathode rays 阴极射线 Joseph John Thomson, 1897 J. J. ThomsonNP1906 1856-1940 SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality — Electron Electron in an Atom Electron: 阴极射线 Cathode rays, Joseph Thomson, 1897 Atoms: 行星模型 Planetary model, Ernest Rutherford, 1911 E. RutherfordNC1908 1871-1937 SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Spectrum of Atomic Hydrogen Spectroscopy , Fingerprints of atoms & molecules ... Atomic Hydrogen Johann Jakob Balmer, 1885 n2 λ = 364:56 n2−4 (nm), n =3,4,5,6 Johannes Rydberg, 1888 1 1 − 1 ν = λ = R( n2 n02 ) R = 109677cm−1 4 × 107/364:56 = 109721 RH = 109677.5834... SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Bohr’s Theory — Electron in Atomic Hydrogen Electron in an Atom Electron: 阴极射线 Cathode rays, Joseph Thomson, 1897 Atoms: 行星模型 Planetary model, Ernest Rutherford, 1911 Spectrum of H: Balmer series, Johann Jakob Balmer, 1885 Quantization energy to H atom, Niels Bohr, 1913 Bohr’s Assumption There are certain allowed orbits for which the electron has a fixed energy. -

The Rydberg Constant

The Rydberg Constant The Rydberg Constant The light you see when you plug in a hydrogen gas discharge tube is a shade of lavender, with some pinkish tint at a higher current. If you observe the light through a spectroscope, you can identify four distinct lines of color in the visible light range. The history of the study of these lines th dates back to the late 19 century, where we meet a high school mathematics teacher from Basel, Switzerland, named Johann Balmer. Balmer created an equation describing the wavelengths of the visible hydrogen emission lines. However, he did not support his equation with a physical explanation. In a paper written in 1885, Balmer proposed that his equation could be used to predict the entire spectrum of hydrogen, including the ultra-violet and the infrared spectral lines. The Balmer equation is shown below. -8 where m and n were integers, and h = 3654.6 10 cm. When one solves the equation using n =2 and m = 3, 4, 5, or 6, the calculated wavelengths are very close to the four emission lines in the visible light range for a hydrogen gas discharge tube. Balmer apparently derived his equation by trail and error. Sadly, he would not live to see Niels Bohr and Johannes Rydberg prove the validity of his equation. Johannes Rydberg was a mathematics teacher like Balmer (he also taught a bit of physics). In 1890, Rydberg’s research of spectroscopy (inspired, it is said, by the work of Dmitri Mendeleev) led to his discovery that Balmer’s equation was a specific case of a more general principle. -

28-1 Line Spectra and the Hydrogen Atom Figure 28.1 Gives Some Examples of the Line Spectra Emitted by Atoms of Gas

28-1 Line Spectra and the Hydrogen Atom Figure 28.1 gives some examples of the line spectra emitted by atoms of gas. The atoms are typically excited by applying a high voltage across a glass tube that contains a particular gas. By observing the light through a diffraction grating, the light is separated into a set of wavelengths that characterizes the element. The spectrum of light emitted by excited hydrogen atoms is shown Figure 28.1: Line spectra from hydrogen (top) and helium in Figure 28.1(a). The decoding of the (bottom). A line spectrum is like the fingerprint of an element. hydrogen spectrum represents one of Astronomers, for instance, can determine what a star is made of by the great scientific mystery stories. carefully examining the spectrum of light emitted by the star. First on the scene was the Swiss mathematician and schoolteacher, Johann Jakob Balmer (1825 – 1898), who published an equation in 1885 giving the wavelengths in the visible spectrum emitted by hydrogen. The Swedish physicist Johannes Rydberg (1854 – 1919) followed up on Balmer’s work in 1888 with a more general equation that predicted all the wavelengths of light emitted by hydrogen: , (Eq. 28.1: The Rydberg equation for the hydrogen spectrum) 7 –1 where R = 1.097 ! 10 m is the Rydberg constant, and the two n’s are integers, with n2 greater than n1. Neither Balmer nor Rydberg had a physical explanation to justify their equations, however, so the search was on for such a physical explanation. The breakthrough was made by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr (1885 – 1962), who showed that if the angular momentum of the electron in a hydrogen atom was quantized in a particular way (related to Planck’s constant, in fact), that the energy levels for an electron within the hydrogen atom were also quantized, with the energies of the electrons being given by: , (Eq. -

Physics P202, Lab #12 Rydberg's Constant

Physics P202, Lab #12 Rydberg’s Constant The light you see when you plug in a hydrogen gas discharge tube is a shade of lavender, with some pinkish tint at a higher current. If you observe the light through a spectroscope, you can identify four distinct lines of color in the visible light range. The history of the study of these lines dates back to the late 19th century, where we meet a high school mathematics teacher from Basel, Switzerland, named Johann Balmer. Balmer created an equation describing the wavelengths of the visible hydrogen emission lines. However, he did not support his equation with a physical explanation. In a paper written in 1885, Balmer proposed that his equation could be used to predict the entire spectrum of hydrogen, including the ultra-violet and the infrared spectral lines. The Balmer equation is shown below. ⎛ n2 ⎞ B⎜ ⎟ λ = ⎜ 2 ⎟ ⎝ (n − 4)⎠ where n is an integer greater than 2 (e.g., 3, 4, 5, or 6), and B = 365.46 nm. When one solves the equation, the calculated wavelengths are very close to the four emission lines in the visible light range for a hydrogen gas discharge tube. Balmer derived his equation by trial and error. Sadly, he would not live to see Niels Bohr prove the validity of his equation. Johannes Rydberg was a mathematics teacher like Balmer. In 1890, Rydberg’s research of spectroscopy led to his discovery that Balmer’s equation was a specific case of a more general principle. Rydberg substituted the wavenumber, 1/wavelength, for wavelength and by applying appropriate constants he developed a variation of Balmer’s equation. -

The Short History of Science

PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR NATURAL PHILOSOPHY PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR www.physicsfoundations.org NATURAL PHILOSOPHY www.lfs.fi Dr. Suntola’s “The Short History of Science” shows fascinating competence in its constructively critical in-depth exploration of the long path that the pioneers of metaphysics and empirical science have followed in building up our present understanding of physical reality. The book is made unique by the author’s perspective. He reflects the historical path to his Dynamic Universe theory that opens an unparalleled perspective to a deeper understanding of the harmony in nature – to click the pieces of the puzzle into their places. The book opens a unique possibility for the reader to make his own evaluation of the postulates behind our present understanding of reality. – Tarja Kallio-Tamminen, PhD, theoretical philosophy, MSc, high energy physics The book gives an exceptionally interesting perspective on the history of science and the development paths that have led to our scientific picture of physical reality. As a philosophical question, the reader may conclude how much the development has been directed by coincidences, and whether the picture of reality would have been different if another path had been chosen. – Heikki Sipilä, PhD, nuclear physics Would other routes have been chosen, if all modern experiments had been available to the early scientists? This is an excellent book for a guided scientific tour challenging the reader to an in-depth consideration of the choices made. – Ari Lehto, PhD, physics Tuomo Suntola, PhD in Electron Physics at Helsinki University of Technology (1971). -

1St Coveoct Issue.Indd

C.K. GHOSH E L C I T RTICLE R A E R U T A UR tryst with mathematical operations begins with EATURE Onumerical identities. Perhaps the fi rst exercise in addition F that we do is 1 + 1=2, which is the simplest among the numerical identities. Likewise, the multiplication tables provide us with numerous examples of numerical identities. The same is true of subtraction or division, which is repeated subtraction. If we probe into many such identities, we fi nd hidden Pythagoras treasures. The focus of this article is such a treasure hunt. Let us look at the identity, 8 + 16 = 24. It may not reveal any meaningful relation. But instead if we have, Take a look at some numerical identities, 9 + 16 = 25, it becomes quite signifi cant. This is because it can be which with some probing reveal hidden expressed as, treasures. Readers may dig out many more 32 + 42 = 52. such identities. In other words, 3, 4, 5 form a Pythagorean Trio. It indicates that if we have a right-angled triangle with its mutually perpendicular sides of length 3 and 4 units, then its hypotenuse The right hand side of identity (a) is 273, which is a number is bound to be of length 5 units. exactly divisible by ‘7’. The le hand side is the sum of the Starting from (3, 4, 5) we may generate many more such number of days in January, February, March, April, May, June, trios, by multiplying each member by 2, 3, 4 and so on. The trios July, August, September of any ordinary year (which is not a leap thus obtained would be (6, 8, 10); (9, 12, 15); (12, 16, 20) and year).