CORI Country Report Bangladesh, March 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

71: How the Bangladeshi War of Independence Has Haunted Tower Hamlets

Institute of Geography Online Paper Series: GEO-020 The Spirit of ’71: how the Bangladeshi War of Independence has haunted Tower Hamlets. Sarah Glynn Institute of Geography, School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, Drummond St, Edinburgh EH8 9XP [email protected] 1 Copyright This online paper may be cited in line with the usual academic conventions. You may also download it for your own personal use. This paper must not be published elsewhere (e.g. mailing lists, bulletin boards etc.) without the author's explicit permission Please note that : • it is a draft; • this paper should not be used for commercial purposes or gain; • you should observe the conventions of academic citation in a version of the following or similar form: Sarah Glynn (2006) The Spirit of ’71: how the Bangladeshi War of Independence has haunted Tower Hamlets, online papers archived by the Institute of Geography, School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh. 2 The Spirit of ’71: how the Bangladeshi War of Independence has haunted Tower Hamlets abstract In 1971 Bengalis in Britain rallied en masse in support of the independence struggle that created Bangladesh. This study explores the nature and impact of that movement, and its continuing legacy for Bengalis in Britain, especially in Tower Hamlets where so many of them live. It looks at the different backgrounds and politics of those who took part, how the war brought them together and politicised new layers, and how the dictates of ‘popular frontism’ and revolutionary ‘stages theory’ allowed the radical socialism of the intellectual leadership to become subsumed by nationalism. -

The Week in Review

THE WEEK IN REVIEW July 07-13, 7(2), 2008 CONTENTS I. COUNTRY REVIEWS………………………….3 A. SOUTH ASIA ………………………...3 B. EAST ASIA …………………………...9 C. WEST ASIA …………………………11 D. US ELECTIONS ……………………..13 II. INTERNAL SECURITY REVIEW ……………..15 III. NUCLEAR REVIEW ………………………….17 EDITOR: S. SAMUEL C. RAJIV REVIEW ADVISOR: S. KALYANARAMAN CONTRIBUTORS M. MAYILVAGANAN – Sri Lanka PRIYADARSHINI SINGH – Energy Security Review, NIHAR NAYAK – Nepal US Election Review JAGANNATH PANDA - China PRIYANKA SINGH – Pakistan S. SAMUEL C. RAJIV – Iraq, Afghanistan ARUN VISHWANATHAN – Nuclear Review MAHTAB ALAM RIZVI – Iran (INDIAN PUGWASH SOCIETY) M. AMARJEET SINGH – Internal Security Review GUNJAN SINGH – Bangladesh, Myanmar, Maldives INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES, 1, DEVELOPMENT ENCLAVE, RAO TULA RAM MARG, NEW DELHI – 110010 IN THE CURRENT ISSUE CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS PAGE 1. COUNTRY 3-15 REVIEW SOUTH ASIA 3-9 Afghanistan NSA blames ISI for July 7 suicide attack; Foreign Secretary visits Kabul; Obama: Indian Embassy attack an indication of the deteriorating security situation; ICRC: Over 250 civilians killed since July 4 Pakistan Serial bomb blasts in Karachi; Suicide bomb attack kills 15 policemen in Islamabad; UN agrees to probe the assassination of Benazir Bhutto Nepal CA passes the Fifth Amendment Bill, Madhesi parties boycott the meeting; Food and fuel crisis intensifies Bangladesh J-e-I files writ petition against Aug 4 elections; Khaleda Zia calls on political parties to work together to overcome current crisis Sri Lanka SLAF claims targeting LTTE -

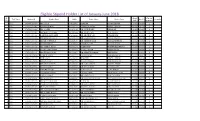

Eligible Stipend Holder List of January-June 2018 Sl

Eligible Stipend Holder List of January-June 2018 Sl. Board Current Tech Name Student ID Student Name Mobile Father Name Mother Name Reg. No. Remarks No. Roll Semester 1 Civil 570676411714904 MD. SAGOR 01743152450 ABDUL HI ROKEYA BEGUM 931498 868586 2 2 Civil 570676411714905 ATIKUR RAHMAN 01757114114 HABIBUR RAHMAN ANWARA BEGUM 931603 868484 2 3 Civil 570676411714906 MD. AL AZIM 01998973145 MD. JAKIR HOSEN USHA BANI 931660 868427 2 4 Civil 570676411714907 MD. MARUFUL ISLAM 01823462565 MD. SHORUZ ALI RENU BEGUM 931711 868373 2 5 Civil 570676411714908 SAMIUL HASSAN ASHIK 01725122222 MD. SHOUKAT ALI ASMA BEGUM 931606 868481 2 6 Civil 570676411714910 MD. MUBINUP HAQUE 01838441811 MD. ASADUZZAMAN MONIJA KHATUN 931631 868456 2 7 Civil 570676411714911 MD. MILON BHUIYAN 01986835164 MD. SIDDIK HOSSAM MST. BANES BEUM 931481 868603 2 8 Civil 570676411714912 SABBIR RAHMAN 01791358824 BAUJID HOSSAIN ROKEYA BEGUM 931580 868506 2 9 Civil 570676411714913 MD. TARIKUL ISLAM 01968181240 KAZIM USSIN NURUNNAHAR BEGUM 931538 868548 2 10 Civil 570676411714914 NASSIR UDDIN JUBAIR 01758398658 HOMAUN KABIR NASIMA AKTER 931581 868505 2 11 Civil 570676411714915 MD. SEYAM HOSSAIN 01915520679 MD. MIZANUR RAHMAN SHULYBEUM 931490 868594 2 12 Civil 570676411714916 ROBIN AHMMED 01793071972 NAZRUL ISLAM SHARMIN AKTER 931676 868411 2 13 Civil 570676411714917 ABID HASAN 01764138490 GIASUDDIN ANWARA BEGUM 931645 868442 2 14 Civil 570676411714918 ASRAJUL ISLAM 01994670952 BULAET HOSSAIN SHAHINA BEGUM 931608 868479 2 15 Civil 570676411714919 MD. IMRAN SARKER 01766702581 MD. LABU SARKER HAMEDA BEGUM 931507 868577 2 16 Civil 570676411714921 RAHAT HOSSAIN 01980253925 MD. RONZU MIAH TOTNA BEGUM 931607 868480 2 17 Civil 570676411714922 EMDADUL HAQUE 01775748866 NORUL HAQUE LOTFA BEGUM 931742 868385 2 18 Civil 570676411714923 HASANUR RAHMAN 01771120299 JAMAAL UDDIN ANOWARA BEGFUM] 931651 868436 2 19 Civil 570676411714924 SOJIB ALI HOSAN 01985294237 MD. -

University of Dhaka B

University of Dhaka B. Sc. in Textile Engineering First Year Admission Test Academic Year: 2014 – 2015 Centre: National Institute of Textile Engineering and Research (NITER) Admission Test Result sorted by Merit Position Total Applicant: 816 Total Present: 530 Sorting Criteria 1 Total Score If equal then 2 Base Score If equal then 3 HSC GPA ex 4th sub If equal then 4 HSC Math If equal then 5 HSC Phy If equal then 6 HSC Chem NITER: B. Sc. in Textile Engineering: Admission Test 2015 P a g e 1 | 11 Merit Exam Roll Full Name Quota Score Position 150105006 Wahed Imtiaz Sheetal 173.60 1 100490 BHUIYA MUHAMMAD JAFRIN 172.00 2 100242 MOHAMMAD JUEL HASAN 171.60 3 150105007 Ehasan Reza 169.20 4 100580 JANNAT JAHAN JOI 168.00 5 100330 MD. SHAKIR RAHMAN 167.00 6 100652 MD. ADIB RAHMAN 166.60 7 100463 MD. TANVIR ALAM 165.80 8 100352 ASHIKUR RAHMAN 165.60 9 100283 A. N. M. NUR UDDIN 165.00 10 100482 BIJON RAY SHUVO 165.00 11 100750 SHOUVIK DAS 164.60 12 100609 MD. YAKUB MOLLA 164.60 13 100685 MD. ABDULLAH AL NOMAN 163.80 14 100191 ONTI BHAKTA 163.00 15 100499 SAADMAN SAYEED 163.00 16 100323 SIFAT AHMED 161.60 17 100278 MD. REDOY AHAMMED 161.60 18 100188 FAYSAL AHMED 161.00 19 100009 FAHMIDA SULTANA 161.00 20 100674 MD RIAZ RAHMAN 160.60 21 100648 MD.ALAMIN SARKER 160.20 22 100288 ZINIA HASSAN NEHA 159.20 23 100621 MYMUNA RAHMAN 159.20 24 100737 AOHONA AREFIN 159.00 25 100332 ALVI RAHMAN 158.20 26 100734 MD. -

The Challenges of Institutionalising Democracy in Bangladesh† Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University

ISAS Working Paper No. 39 – Date: 6 March 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Challenges of Institutionalising † Democracy in Bangladesh Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University Contents Executive Summary i-iii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Challenges of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: A Global Discourse 4 3. The Challenge of Organising Free and Fair Elections 7 4. The Challenge of Establishing the Rule of Law 19 5. The Challenge of Guaranteeing Civil Liberties and Fundamental Freedoms 24 6. The Challenge of Ensuring Accountability 27 7. Conclusion 31 Appendix: Table 1: Results of Parliamentary Elections, February 1991 34 Table 2: Results of Parliamentary Elections, June 1996 34 Table 3: Results of Parliamentary Elections, October 2001 34 Figure 1: Rule of Law, 1996-2006 35 Figure 2: Political Stability and Absence of Violence, 1996-2006 35 Figure 3: Control of Corruption, 1996-2006 35 Figure 4: Voice and Accountability, 1996-2006 35 † This paper was prepared for the Institute of South Asian Studies, an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. ∗ Professor Rounaq Jahan is a Senior Research Scholar at the Southern Asian Institute, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University. She can be contacted at [email protected]. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bangladesh joined what Samuel P. Huntington had called the “third wave of democracy”1 after a people’s movement toppled 15 years of military rule in December 1990. In the next 15 years, the country made gradual progress in fulfilling the criteria of a “minimalist democracy”2 – regular free and contested elections, peaceful transfer of governmental powers as a result of elections, fundamental freedoms, and civilian control over policy and institutions. -

Bangladesh Country of Origin Information (COI) Report COI Service

Bangladesh Country of Origin Information (COI) Report COI Service Date 31 August 2013 Bangladesh 31 August 2013 Contents Go to End Preface Background Information 1. Geography ................................................................................................................... 1.01 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 Map of Bangladesh ............................................................................................... 1.08 Other maps of Bangladesh ................................................................................. 1.09 2. Economy ...................................................................................................................... 2.01 3. History .......................................................................................................................... 3.01 Pre-independence: 1905- 1971 ............................................................................ 3.01 Post-independence: 1972 - 2012 ....................................................................... 3.03 General Election of 29 December 2008 ............................................................... 3.08 Political parties which contested the general election ........................................ 3.09 Results of the general election ........................................................................... 3.10 Post-election violence ....................................................................................... -

Yearbook Peace Processes.Pdf

School for a Culture of Peace 2010 Yearbook of Peace Processes Vicenç Fisas Icaria editorial 1 Publication: Icaria editorial / Escola de Cultura de Pau, UAB Printing: Romanyà Valls, SA Design: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Legal registry: This yearbook was written by Vicenç Fisas, Director of the UAB’s School for a Culture of Peace, in conjunction with several members of the School’s research team, including Patricia García, Josep María Royo, Núria Tomás, Jordi Urgell, Ana Villellas and María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas also holds the UNESCO Chair in Peace and Human Rights at the UAB. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford, won the National Human Rights Award in 1988, and is the author of over thirty books on conflicts, disarmament and research into peace. Some of the works published are "Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados” (“Peace Processes and Negotiation in Armed Conflicts”), “La paz es posible” (“Peace is Possible”) and “Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos” (“Peace Culture and Conflict Management”). 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Definitions and typologies 5 Main Conclusions of the year 7 Peace processes in 2009 9 Main reasons for crises in the year’s negotiations 11 The peace temperature in 2009 12 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years 13 Common phases in negotiation processes 15 Special topic: Peace processes and the Human Development Index 16 Analyses by countries 21 Africa a) South and West Africa Mali (Tuaregs) 23 Niger (MNJ) 27 Nigeria (Niger Delta) 32 b) Horn of Africa Ethiopia-Eritrea 37 Ethiopia (Ogaden and Oromiya) 42 Somalia 46 Sudan (Darfur) 54 c) Great Lakes and Central Africa Burundi (FNL) 62 Chad 67 R. -

Bangladesh Page 1 of 20

Bangladesh Page 1 of 20 Bangladesh Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2007 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 11, 2008 Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy of 150 million citizens. Khaleda Zia, head of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), stepped down as prime minister in October 2006 when her five-year term of office expired and transferred power to a caretaker government that would prepare for general elections scheduled for January 22. On January 11, in the wake of political unrest, President Iajuddin Ahmed, the head of state and then head of the caretaker government, declared a state of emergency and postponed the elections. With support from the military, President Ahmed appointed a new caretaker government led by Fakhruddin Ahmed, the former Bangladesh Bank governor. In July Ahmed announced that elections would be held by the end of 2008, after the implementation of electoral and political reforms. While civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces, these forces frequently acted independently of government authority. The government's human rights record worsened, in part due to the state of emergency and postponement of elections. The Emergency Powers Rules of 2007 (EPR), imposed by the government in January and effective through year's end, suspended many fundamental rights, including freedom of press, freedom of association, and the right to bail. The anticorruption drive initiated by the government, while greeted with popular support, gave rise to concerns about due process. For most of the year the government banned political activities, although this policy was enforced unevenly. -

33Rd WEDC International Conference, City, Country, 2007

AHMED, JAHAN, BALA & HALL 35th WEDC International Conference, Loughborough, UK, 2011 THE FUTURE OF WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE: INNOVATION, ADAPTATION AND ENGAGEMENT IN A CHANGING WORLD Inclusive sanitation: breaking down barriers S. Ahmed, H Jahan, B. Bala & M. Hall, Bangladesh BRIEFING PAPER 1132 During implementation of WaterAid Bangladesh’s current project it became evident that certain populations were unintentionally being excluded – people with disabilities were one of these groups. Social stigmas and access difficulties meant that they were not present in CBOs or hygiene promotional sessions and excluded from decision making activities, resulting in continued open defecation and other unhygienic behaviours. The linkages between poverty and disability are strong, with disability being both the cause and effect of poverty. Without specific activities to address the requirements of people with disabilities the cycle of poverty remains, further exacerbated by continued exclusion from services such as health care, education and water and sanitation. This paper concentrates on the barriers faced by people with disabilities in accessing water and sanitation services and explains how through WaterAid Bangladesh’s recent initiative, a greater understanding on breaking these barriers is strengthening the future interventions. WaterAid Bangladesh — achieving sustainable environmental health WaterAid Bangladesh (WAB) has been working in Bangladesh implementing water, sanitation and hygiene promotion activities since 1986. In 2004 WAB started a 5-year DFID funded project called ‘Achieving Sustainable Environmental Health’ (ASEH) which aimed at reaching the poorest, geographically excluded people living in hydro-geologically difficult areas of the country. In little over 5 years the project has reached nearly 6million beneficiaries with safe and sustainable water, sanitation and hygiene promotional activities in both urban and rural areas. -

India's National Security Annual Review 2010

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 216x138 HB + 8colour pages ii Ç India’s National Security This series, India’s National Security: Annual Review, was con- ceptualised in the year 2000 in the wake of India’s nuclear tests and the Kargil War in order to provide an in-depth and holistic assessment of national security threats and challenges and to enhance the level of national security consciousness in the country. The first volume was published in 2001. Since then, nine volumes have been published consecutively. The series has been supported by the National Security Council Secretariat and the Confederation of Indian Industry. Its main features include a review of the national security situation, an analysis of upcoming threats and challenges by some of the best minds in India, a periodic National Security Index of fifty top countries of the world, and a chronology of major events. It now serves as an indispensable source of information and analysis on critical national security issues of India. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Editor-in-Chief SATISH KUMAR Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI Under the auspices of Foundation for National Security Research, New Delhi First published 2011 in India by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2011 © 2010 Satish Kumar Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Ltd D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, NOIDA 201 301 All rights reserved. -

List of Trainees of Egp Training

Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Summary of Participants # Type of Training No. of Participants 1 Procuring Entity (PE) 876 2 Registered Tenderer (RT) 1593 3 Organization Admin (OA) 59 4 Registered Bank User (RB) 29 Total 2557 Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Number of Procuring Entity (PE) Participants: 876 # Name Designation Organization Organization Address 1 Auliullah Sub-Technical Officer National University, Board Board Bazar, Gazipur 2 Md. Mominul Islam Director (ICT) National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 3 Md. Mizanoor Rahman Executive Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 4 Md. Zillur Rahman Assistant Maintenance Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 5 Md Rafiqul Islam Sub Assistant Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 6 Mohammad Noor Hossain System Analyst National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 7 Md. Anisur Rahman Programmer Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-999 8 Sanjib Kumar Debnath Deputy Director Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-1000 9 Mohammad Rashedul Alam Joint Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 10 Md. Enamul Haque Assistant Director(Construction) Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 11 Nazneen Khanam Deputy Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 12 Md. -

List of Unclaimed Cash Dividend for the Year 2015 Net Dividend Amount Sl

List of Unclaimed Cash Dividend for the year 2015 Net Dividend Amount Sl. No. Folio No. Name of Shareholder Father's name Mother's Name Address (TK) 1 25 KAFILUDDIN MAHMOOD - - HOUSE NO.72, ROAD NO., 11 A DHANMONDI R/A,, , DHAKA 1,091.40 2 37 TAHERUDDIN AHMED - - 10/14, IQBAL ROAD,, 1ST FLOOR MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207, DHAKA 340.00 3 63 MOHAMMAD BARKAT ULLAH - - C/O Y A KHAN, HOUSE NO.17, ROAD NO-6, , DHANMONDI R/A, DHAKA, , DHAKA 340.00 4 107 MD RAMJAN ALI - - KALLAYANPUR HOUSING ESTATEBLDG-1, , FLAT-7, DARUS SALAM ROADMIRPUR, DHAKA, DHAKA 255.00 5 141 MUHAMMAD ABDUL WAHHAB - - HOUSE NO. 63, , AVENUE-5BLOCK-A, SECTION-6, MIRPUR, DHAKA-1216, DHAKA 170.00 6 152 MD SHAHIDUL ISLAM - - SHAHNAJ MOHAL 257/2, JAFRABAD, , WEST DHANMONDI , DHAKA 2,995.40 7 221 N R PARVEZ - - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK, (ADB/BROBSEC BHABAN, PLOT NO. E-31, SHER-E-BANGLA NAGAR, DHAKA 17.00 8 224 MD ABUL QUASHEM - - 106, MOGH BAZARKAZI OFFICE LANE, , , 1,020.00 9 282 NESARUDDIN MOHAMMED OLIULLAH - - FLAT # A-5 HOUSE # CEN (A)3,, ROAD # 96, GULSHAN-2,DHAKA., 374.00 10 392 MD ABDUL NAYEEM - - 48, DINA NATH SEN ROAD, GANDARIA, DHAKA 4,088.50 11 396 MD GOLAM FARUQUE - - 368/A, KHILGAON, DHAKA-1219, , , 205.70 12 400 DURRIYAH AHMED - - 63, DOHS(BANANI) , STREET NO-5DHAKA CANTT., DHAKA 1,357.45 13 404 NARINA SULTANA - - 117 BAROMOGH BAZARGROUND FLOOR, DHAKA-1217, , 1,357.45 14 432 AGHA YUSUF - - JATIYA SCOUT BHABAN70/1, , PURANA PALTAN LINE, (12TH FLOOR) KAKRAIL, DHAKA, 4,088.50 15 434 DR MD SHAHJAHAN MIAH - - 56/1, NAYA PALTAN, DHAKA-1000, , , 2,449.70 16 452 ROUSHON JAHAN -