Fascism Fascism History and Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germany: a Global Miracle and a European Challenge

GLOBAL ECONOMY & DEVELOPMENT WORKING PAPER 62 | MAY 2013 Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS GERMANY: A GLOBAL MIRACLE AND A EUROPEAN CHALLENGE Carlo Bastasin Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS Carlo Bastasin is a visiting fellow in the Global Economy and Development and Foreign Policy pro- grams at Brookings. A preliminary and shorter version of this study was published in "Italia al Bivio - Riforme o Declino, la lezione dei paesi di successo" by Paolazzi, Sylos-Labini, ed. LUISS University Press. This paper was prepared within the framework of “A Growth Strategy for Europe” research project conducted by the Brookings Global Economy and Development program. Abstract: The excellent performance of the German economy over the past decade has drawn increasing interest across Europe for the kind of structural reforms that have relaunched the German model. Through those reforms, in fact, Germany has become one of the countries that benefit most from global economic integration. As such, Germany has become a reference model for the possibility of a thriving Europe in the global age. However, the same factors that have contributed to the German "global miracle" - the accumulation of savings and gains in competitiveness - are also a "European problem". In fact they contributed to originate the euro crisis and rep- resent elements of danger to the future survival of the euro area. Since the economic success of Germany has translated also into political influence, the other European countries are required to align their economic and social models to the German one. But can they do it? Are structural reforms all that are required? This study shows that the German success depended only in part on the vast array of structural reforms undertaken by German governments in the twenty-first century. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

ITALY: Five Fascists

Da “Time”, 6 settembre 1943 ITALY: Five Fascists Fascismo's onetime bosses did not give up easily. Around five of them swirled report and rumor: Dead Fascist. Handsome, bemedaled Ettore Muti had been the "incarnation of Fascismo's warlike spirit," according to Notizie di Roma. Lieutenant colonel and "ace" of the air force, he had served in Ethiopia, Spain, Albania, Greece. He had been Party secretary when Italy entered World War II. Now the Badoglio Government, pressing its purge of blackshirts, charged him with graft. Reported the Rome radio: Ettore Muti, whipping out a revolver, resisted arrest by the carabinieri. In a wood on Rome's outskirts a fusillade crackled. Ettore Muti fell dead. Die-Hard Fascist. Swarthy, vituperative Roberto Farinacci had been Fascismo's hellion. He had ranted against the democracies, baited Israel and the Church, flayed Fascist weaklings. Ex-Party secretary and ex-minister of state, he had escaped to Germany after Benito Mussolini's fall. Now, in exile, he was apparently building a Fascist Iron Guard. A Swiss rumor said that Roberto Farinacci had clandestine Nazi help, that he plotted a coup to restore blackshirt power, that he would become pezzo grosso (big shot) of northern Italy once the Germans openly took hold of the Po Valley. Craven Fascist. Tough, demagogic Carlo Scorza had been Fascismo's No. 1 purger. Up & down his Tuscan territory, his ghenga (corruption of "gang") had bullied and blackmailed. He had amassed wealth, yet had denounced the wartime "fat and rich." Now, said a Bern report, Carlo Scorza wrote from prison to Vittorio Emanuele, offering his services to the crown. -

Byron, Orwell, Politics, and the English Language Peter Graham As I

Byron, Orwell, Politics, and the English Language Peter Graham As I began thinking about this lecture for the Kings College IBS it hit home that my first such presentation was 31 years ago, way back in 1982 at Groeningen. Some of the people who were there then are now gone (I think for instance of Elma Dangerfield, so formidable a presence in so small a package, and of Andrew Nicolson, who was celebrating his contract to edit Byron’s prose). Many others who were young and promising then are now three decades less young and more accomplished. Whatever: I hope you’ll bear with a certain amount of nostalgia in the ensuing talk—nostalgia and informality. The goal will be to make some comparative comments on two literary figures familiar to you all—and to consider several texts by these writers, texts that powerfully changed how I thought about things political and poetical when a much younger reader and thinker. The two writers: Eric Blair, better known to the reading public as George Orwell, and Lord Byron. The principal texts: Orwell’s essays, particularly “Politics and the English Language,” and and Byron’s poetico-political masterpiece Don Juan. Let’s start with the men, both of them iconic examples of a certain kind of liberal ruling-class Englishman, the rebel who flouts the strictures of his class, place, and time but does so in a characteristically ruling-class English way. Both men and writers display an upmarket version of the “generous anger” that Orwell attributes to Charles Dickens in a description that perfectly fits Byron and, with the change of one word, fits Orwell himself: “a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls” 2 Byron’s and Orwell’s iconically rebellious lives and iconoclastic writing careers bookend the glory days of the British Empire. -

Executive–Legislative Relations and the Transition to Democracy from Electoral Authoritarian Rule

MWP 2016/01 Max Weber Programme The Peril of Parliamentarism? Executive–legislative Relations and the Transition to Democracy from Electoral Authoritarian Rule AuthorMasaaki Author Higashijima and Author and Yuko Author Kasuya European University Institute Max Weber Programme The Peril of Parliamentarism? Executive–legislative Relations and the Transition to Democracy from Electoral Authoritarian Rule Masaaki Higashijima and Yuko Kasuya EUI Working Paper MWP 2016/01 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7728 © Masaaki Higashijima and Yuko Kasuya, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract Why do some electoral authoritarian regimes survive for decades while others become democracies? This article explores the impact of constitutional structures on democratic transitions from electoral authoritarianism. We argue that under electoral authoritarian regimes, parliamentary systems permit dictators to survive longer than they do in presidential systems. This is because parliamentary systems incentivize autocrats and ruling elites to engage in power sharing and thus institutionalize party organizations, and indirectly allow electoral manipulation to achieve an overwhelming victory at the ballot box, through practices such as gerrymandering and malapportionment. We test our hypothesis using a combination of cross-national statistical analysis and comparative case studies of Malaysia and the Philippines. -

U.S. and USSR Bilateral Relations

US AND USSR RELATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Afghanistan William W. Lehfeldt 1952-1955 Administrative Assistant, Technical Cooperation Administrative, Kabul Armin H. Meyer 1955-1957 Deputy Chief of Mission, Kabul Bruce A. Flatin 1957-1959 Political/Economic/Consular officer, Kabul William D. Brewer 1962-1965 Deputy Chief of Mission, Kabul William Piez 1963-1966 Ecnomic/Political Officer, Kabul Archer K. Blood 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Kabul Victor Skiles 1969-1972 Deputy Director, USAID, Kabul Arnold Schifferdecker 1970-1972 Political Officer, Kabul Bruce A. Flatin 1977-1979 Political Counselor, Kabul James E. Taylor 1977-1980 Political Officer, Kabul Rudolf V. Perina 1979-1981 Political Officer, Moscow, Soviet Union Ernestine S. Heck 1980-1983 State Department; Afghanistan Desk Officer, Washington, DC Jon David Glassman 1987-1989 Chargé, Kabul Azerbaijan John P. Harrod 1975-1978 Exhibit Officer, USIS, Moscow Michael W. Cotter 1995-1998 Ambassador, Turkmenistan China 1960-1964 Economic Officer, Hong Kong Edwin Webb Martin 1945-1948 Chinese Language Training, Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) and Beijing 1948-1949 Consular Officer, Hankow 1949-1950 Economic Officer, Taipei, Taiwan 1951-1955 Political Officer, Office of Chinese Affairs, Washington, DC 1953-1954 Political Advisor to Talks with Chinese, Panmunjom, Korea 1955 Talks with Chinese, Geneva, Switzerland 1958-1961 Office of Chinese Affairs, Washington, DC 1961-1964 Political Advisor, Commander in Chief, Pacific 1967-1970 Consul General, Hong Kong Marshall Green 1956-1960 -

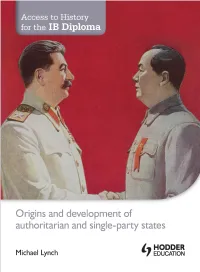

Origins and Developments of Authoritarian and Single-Part States

Access to History for the IB Diploma Origins and development of authoritarian and single-party states Michael Lynch For Elizabeth Suzanne Clare The material in this title has been developed independently of the International Baccalaureate®, which in no way endorses it. The Publishers would like to thank the following for permission to reproduce copyright material: Photo credits p.33 Bettmann/Corbis; p.41 © David King Collection; p.48 t © Fotosearch/Getty Images, b © Michael Nicholson/Corbis; p.89 © Photos 12/Alamy; p.93 © 2000 Topham Picturepoint/TopFoto; p.97 © Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive; p.112 © Cody Images; p.123 © Bettmann/Corbis; p.182 © 2003 Topham Picturepoint/TopFoto; p.210 © OFF/AFP/Getty Images; p.224 © Picture Alliance/Photoshot; p.245 © AP/Press Association Images; p.257 Poster courtesy of the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Plakatsammlung, © ZHdK; p.272 © AP/Press Association Images; p.295 © TopFoto; p.312 © Roger-Viollet/TopFoto. Acknowledgements Guy Arnold: from Africa: A Modern History (Atlantic Books, 2005); IndexMundi: Tables: Infant mortality rates in different countries and regions; Life expectancy in different countries and regions; Literacy rates in different countries and regions, from www.indexmundi.com; Guido Indij: ‘The Twenty Truths’, quoted in Perón Meidante, translated by Mitchell Abidor (La Manca Editora, 2006); Robert Service: from Stalin: A Biography (Macmillan, 2004); World Bank: Table showing World Development Indicators for Tanzania, from Bank/Tanzania Relations, 1990. PFPs, IMF RED (1999). Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the Publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. -

Religious Toleration in English Literature from Thomas More to John Milton

Religious Toleration in English Literature from Thomas More to John Milton Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Justin R. Pepperney, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: John N. King, Advisor Christopher Highley Luke Wilson Copyright by Justin R. Pepperney 2009 Abstract The purpose of this dissertation is to examine how the idea of religious toleration was represented in early modern English polemical prose, poetry, and other literary genres. I argue that religious toleration extends from what is permissible in spiritual practice and belief, to what is permissible in print, and texts on religious toleration encouraged writers to contemplate the status of the discourse to which they contributed. Although the study begins and ends with analysis of two authors whose writings on toleration have received extensive critical attention, this dissertation also applies the latest theoretical framework for understanding religious toleration to writers whose contribution to the literature of toleration has previously been less well documented. Thomas More‘s Utopia (1516) outlines an ideal state with apparently progressive institutions and social practices, including property shared in common, abolition of the monetary system, and religious toleration. Contrary to the view of previous criticism, however, the image of a tolerant society in More‘s Utopia is unlike the modern ideal of toleration as a foundational principal of modern pluralism. Although More also argued against toleration of heresy in his later polemical works, he engaged with the concept of toleration to contemplate the efficacy of the dialogue as a persuasive tool. -

Open Beckman Bruce Eaglebullhistory

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The Eagle and the Bull: United States Relations With Francoist Spain during World War II BRUCE BECKMAN Spring 2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in History and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Anne Rose Distinguished Professor of History and Religious Studies Thesis Supervisor Cathleen Cahill Associate Professor of History Honors Advisor *Signatures on file at the Schreyer Honors College i Abstract This thesis argues that the relationship between the United States and Spain played a significant part in maintaining the neutrality of Spain and had a considerable effect on the outcome of the war. It is largely based on research done at The Columbia University Rare Book Library on the Carlton J.H. Hayes Papers, 1920-1962. These papers were the records of the Ambassador of the United States to Spain, Carlton J.H. Hayes, and contained his personal notes and correspondence in addition to official communications and letters that he wrote as Ambassador to Spain. Utilizing the hundreds of pages contained in this archive was essential in gaining access to a unique set of primary sources that placed the United States-Spanish relationship in a context previously unexplored. Where before, there was little secondary research on the American relationship with Spain during World War II, and even fewer that utilized the writings of Carlton Hayes, this thesis explores a new avenue of research on a little explored subject. Additionally, Ambassador Hayes’ personal notes and correspondence provided a window into the mind of an individual whose experiences during World War II were singular and reflective of his responsibilities during the war. -

Death of a Nationalist Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DEATH OF A NATIONALIST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rebecca Pawel | 280 pages | 01 Mar 2004 | Soho Press Inc | 9781569473443 | English | New York, United States Death of a Nationalist PDF Book Sep 09, Jim rated it liked it. Part of a series on. Original Title. Jimenez, bureaucratic Lt. Core values. The Turncoat. Grayling describes nations as artificial constructs, "their boundaries drawn in the blood of past wars". But I enjoyed it. Benedict Anderson argued that anti-colonial nationalism is grounded in the experience of literate and bilingual indigenous intellectuals fluent in the language of the imperial power, schooled in its "national" history, and staffing the colonial administrative cadres up to but not including its highest levels. Please enter a valid email address. We also meet the fiance of the Aunt who himself a devout Communist is trying to find out who killed her and so we have dual storylines as everyone attempts to solve the mystery. Laland and Brown report that "the vast majority of professional academics in the social sciences not only Like on Facebook. Theories of Nationalism: A Critical Introduction 2nd ed. Friend Reviews. The Case of Lisandra P. The characters are described as cunning and tough, but they then make absurdly bad choices or "accidentally" give themselves away. Oct 31, Blaine DeSantis rated it really liked it. I didn't care enough about the characters though I felt sorry for everyone. See also: Types of nationalism. The Madonna of the Sleeping Cars. Prominent theorists who developed the modernist interpretation of nations and nationalism include: Carlton J. When communism fell in Yugoslavia, serious conflict arose, which led to the rise in extreme nationalism. -

Download the Publication

Nuclear Proliferation International History Project "Is the Possibility of a Third World War Real?" Researching Nuclear Ukraine in the KGB Archive By Nate Jones NPIHP Working Paper #13 March 2019 THE NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Leopoldo Nuti, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project. The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project (NPIHP) is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews and other empirical sources. Recognizing that today’s toughest nuclear challenges have deep roots in the past, NPIHP seeks to transcend the East vs. West paradigm to work towards an integrated international history of nuclear weapon proliferation. The continued proliferation of nuclear weapons is one of the most pressing security issues of our time, yet the empirically-based study of international nuclear history remains in its infancy. NPIHP’s programs to address this central issue include: the annual Nuclear Boot Camp for M.A. and Ph.D. candidates to foster a new generation of experts on the international history of nuclear weapons; the NPIHP Fellowship Program for advanced Ph.D. students and post-doctoral researchers hosted by NPIHP partner institutions around the world; a coordinated, global research effort which combines archival mining and oral history interviews conducted by NPIHP partners; a massive translation and digitization project aimed at making documentary evidence on international nuclear history broadly accessible online; a series of conferences, workshops and seminars hosted by NPIHP partners around the world. -

Iranians in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates: Migration, Minorities, and Identities in the Persian Gulf Arab States

Iranians in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates: Migration, Minorities, and Identities in the Persian Gulf Arab States Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors McCoy, Eric Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 17:09:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193398 IRANIANS IN BAHRAIN AND THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES MIGRATION, MINORITIES, AND IDENTITIES IN THE PERSIAN GULF ARAB STATES by Eric Andrew McCoy ___________________________ Copyright © Eric A. McCoy 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Eric A. McCoy APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: _______________________________ ______________________ Kamran Talattof Date Professor of Near Eastern Studies 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been completed without the help of many individuals and organizations, although I only mention a select few here.