Thomas Rickert and Michael Salvo Interviewed by Dave Rieder Mike

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanks: a Festival Everyone Can Enjoy

Hanks: A festival everyone can enjoy http://www.statesman.com/opinion/hanks-a-festival-everyone-can-enjoy-... Print this page Close Hanks: A festival everyone can enjoy Anna Hanks, LOCAL CONTRIBUTOR Published: 6:45 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 12, 2010 I had an unexpected realization during the Flaming Lips set at the Austin City Limits Music Festival. Watching the Oklahoma-based band closing their show with "Do You Realize??" I discovered tears steaming down my face. I was so embarrassed that I quickly donned my sunglasses, hoping no one noticed. The song includes the following lyrics sung slowly by the Lips' frontman Wayne Coyne: "Do you realize — that everyone you know someday will die And instead of saying all of your goodbyes — let them know You realize that life goes fast It's hard to make the good things last ... " Listening to the lyrics, I started thinking about how fragile our bodies really are. They bleed. Things break. They don't especially enjoy the unaccustomed exercise of traipsing around Zilker Park for three days in the sun. I spent a lot of time thinking about bodies and physical limitations while talking to people using the festival's accommodations for people with disabilities. Yet it wasn't until seeing the Flaming Lips play that song that I examined why I had chosen to write about this issue. A dozen years ago, my father started using a wheelchair. Since then, I've spent considerable time determining what's really accessible for a large man in a power chair. Thus, I often notice curb cuts, handicap bathrooms and well-located wheelchair ramps. -

Album of the Week: the Flaming Lips' Oczy Mlody

Album Of The Week: The Flaming Lips’ Oczy Mlody There are bands that do unique and weird things, and then there’s The Flaming Lips. Things have changed a lot since the band started out as “the punks on acid” in the early ‘80s and then gradually became an enigmatic and psychedelic act of wonder. The core members of Wayne Coyne, Michael Ivins and Steven Drozd always manage to delve into different territory and push the artistic envelope with each release. Their latest, Oczy Mlody, takes the senses to a totally different place. Soothing tones and hypnotic vibes are abundant from start to finish. It’s The Flaming Lips’ first album without longtime drummer Kliph Spurlock who left after the making of the band’s previous album, The Terror, in 2014. There are orchestral dimensions and extravagant structures that make up parts of each track. Coyne’s vocals seem like they’re traveling over the rhythms and beats as if on a voyage. It seems like the band has gone further toward the electronic realm while retaining their psychedelic roots. The album goes along with the space aesthetics that have always been a part of The Flaming Lips’ sound. A dream pop presence is noticeable while the wide-ranging arrangements keep the album from becoming redundant and boring. For a band as limitless as The Flaming Lips, there’s not a lot that can be predicted when a new release is put out. Oczy Mlody is a great example of how Coyne and company can progress their art and present new things more than 30 years later. -

Places to Go, People To

Hanson mistakenINSIDE EXCLUSIVE:for witches, burned. VerThe Vanderbilt Hustler’s Arts su & Entertainment Magazine s OCTOBER 28—NOVEMBER 3, 2009 VOL. 47, NO. 23 VANDY FALL FASHION We found 10 students who put their own spin on this season’s trends. Check it out when you fl ip to page 9. Cinematic Spark Notes for your reading pleasure on page 4. “I’m a mouse. Duh!” Halloween costume ideas beyond animal ears and hotpants. Turn to page 8 and put down the bunny ears. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31 The Regulars The Black Lips – The Mercy Lounge Jimmy Hall and The Prisoners of Love Reunion Show The Avett Brothers – Ryman Auditorium THE RUTLEDGE The Mercy Lounge will play host to self described psychedelic/ There really isn’t enough good to be said about an Avett Brothers concert. – 3rd and Lindsley 410 Fourth Ave. South 37201 comedy band the Black Lips. With heavy punk rock infl uence and Singing dirty blues and southern rock with an earthy, roots The energy, the passion, the excitement, the emotion, the talent … all are 782-6858 mildly witty lyrics, these Lips are not Flaming but will certainly music sound, Jimmy Hall and his crew stick to the basics with completely unrivaled when it comes to the band’s explosive live shows. provide another sort of entertainment. The show will lean towards a songs like “Still Want To Be Your Man.” The no nonsense Whether it’s a heart wrenchingly beautiful ballad or a hard-driving rock punk or skaa atmosphere, though less angry. -

16—29 JULY 2018 Giaf.Ie NEVER MISS OUT

CULTUREFOX.IE GALWAY INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 16–29 JULY 2018 JULY 16–29 FESTIVAL ARTS INTERNATIONAL GALWAY 16—29 JULY 2018 giaf.ie NEVER MISS OUT The Arts Council’s new, upgraded CULTUREFOX events guide is now live. Free, faster, easy to use – and personalised for you. Never miss out again. Contents Theatre, Opera, Circus & Dance 4 Street Art & Spectacle 26 Music 30 Visual Arts 52 First Thought Talks 60 Comedy 68 Booking, Information & Festival Club 74 Venues & Map 75 Festival Diary 76 Festival Garden This year we introduce the new Festival Garden — the home Eyre Square of the Festival in the heart of Galway. Enjoy a chilled out 18–29 July, 12noon–10pm BOOK NOW at giaf.ie atmosphere at the new Festival Lounge with great food and Free In person from 18 June at drinks, occasional DJs and live sets from guest artists. With Festival Box Office, Galway Tourist Office, a Festival Information Centre & Box Office, the new Festival Forster Street, Galway, Ireland Garden is a great new space for artists and audiences alike Phone: +353 91 566 577 to come together and join in the celebration. IMAGE: MUSEUM OF THE MOON [SEE PAGE 27] – PHOTO: ED SIMMONS #GIAF18 1 Funding Agencies & Sponsors Government Support Corporate Support PRINCIPAL FUNDERS LEADERSHIP PARTNER EDUCATION PARTNER Festival Staff DRINKS PARTNER Chief Executive Selected John Crumlish Shelley Troupe, Manager ® Artistic Director Artist Liaison Paul Fahy Philip Sweeney, Michael Mulroy Hugh Lavelle, Liam Parkinson Financial Controller FESTIVAL PARTNERS Gerry Cleary Photography & Filming -

History of 3D Sound

HISTORY OF 3D SOUND BRAXTON BOREN American University Introduction The history of 3D sound is complicated by the fact that, despite how much the concept may appear to be a late-20th century technological buzzword, it is not at all new. Indeed, just as Jens Blauert famously reminded us that “there is no non-spatial hearing” (Blauert, 1997), so too due to the nature of our world all sound is inherently three-dimensional (Begault, 2000). For the majority of human history the listener – the hunter in the field, a singing congregant within a cavernous stone church, or the audience member at a live performance – perceived sound concomitantly with its spatial setting. In this sense it is the late-20th century view that is out of step with historical sound perception. The advent of audio recording in the 19th century led to the development of zero-dimensional (mono) sound, and later one-dimensional (stereo), and two-dimensional (quad and other surround formats) reproduction techniques. Due to the greater sensitivity of the human auditory system along the horizontal plane, early technology understandably focused on this domain. Our capability to mechanically synthesize full 3D auditory environments is relatively recent, compared to our long history of shaping sound content and performance spaces. The effect of physical space is not limited to the perceived physical locations of sounds – different spaces can also affect music in the time domain (e.g. late reflection paths) or frequency 1 domain (by filtering out high-frequency content). Often a listener’s experience of a space’s effect on sound – such as singing in the shower or listening to a choir in a reverberant stone church – is describing primarily non-localized qualities, which could be captured more or less in a monaural recording. -

The Flaming Lips

ISSUE #37 MMUSICMAG.COM ISSUE #37 MMUSICMAG.COM Q&A Was taking on the Beatles intimidating? is. My energy and my focus are part of we could quit our restaurant jobs and figure There are three groups: People who love the what gets it from being an idea to getting out how to make our records and shows Beatles and love what we did; people who it done. That doesn’t mean it’s all worth better. This went on for three or four years don’t care about the Beatles and what we did; doing—but that’s what creative people do: without anyone coming in and saying “Wait and the third group who love the Beatles and create. The more you do it, the more freedom a minute, what are you freaks doing?” That think if you try to do their music you should you have to do stuff, and the less you was a great time for us to take it seriously and be killed. We try not to think about those get hung up on it. work hard. We were fortunate that it worked freaks. The Beatles music is out there—and and we were able to keep going. doing our version doesn’t harm their version. Was it like this in the beginning? Being creative doesn’t mean you only create Is a new album in the works? How did you choose the artists? good things. The mistake people make is that It’s like we do so much stuff that sometimes Most are friends of ours who are not famous they don’t want to do anything that’s bad, so we forget. -

Radio K Top 77 of 2002 1 Beck Sea Change Geffen 2 the Flaming Lips

Radio K Top 77 of 2002 1 Beck Sea Change Geffen 2 The Flaming Lips Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots Warner 3 The Soviettes S/T 7" AND S/T split EP (with The Valentines) Pop Riot 4 Sleater Kinney One Beat Kill Rock Stars 5 Tegan and Sara If It Was You Vapor 6 Sigur Ros ( ) PIAS America 7 Wilco Yankee Hotel Foxtrot Nonesuch 8 Interpol Turn on the Bright Lights Matador 9 Clinic Walking With Thee Domino 10 Selby Tigers Curse Of The Selby Tigers Hopeless 11 RJD2 Deadringer Definite Jux 12 Mclusky Mclusky Do Dallas Too Pure 13 Paul Westerberg Stereo Vagrant 14 A Whisper in the Noise Throught the Ides of March (self-released) 15 Jurassic 5 Power In Numbers Interscope 16 Low Trust Kranky 17 Mark Mallman The Red Bedroom Guilt Ridden Pop 18 Johnny Cash The Man Comes Around Lost Highway 19 Har Mar Superstar You Can Feel Me Record Collection 20 Spoon Kill the Moonlight Merge 21 12 Rods Lost Time (self-released) 22 Tom Waits Alice Anti 23 Atmosphere God Loves Ugly Rhymesayers Black Heart 24 Amore Del Tropico Touch and Go Procession 25 Traditional Methods S/T (self-released) Pretty Girls Make 26 Good Health Lookout! Graves 27 Dillinger Four Situationist Comedy Fat Wreck Chords 28 Aimee Mann Lost In Space SuperEgo 29 Sahara Hotnights Jennie Bomb Jetset 30 White Stripes B-Sides from White Blood Cells V2 31 Neko Case Blacklisted Bloodshot 32 Ladytron Light & Magic Emperor Norton 33 Work of Saws The Pious Flats Thick Furniture 34 Mary Lou Lord Speeding Motorcycle Rubric 35 Apartment Music V/A Free Election There Is No Beginning to the Story EP AND Lifted 36 Bright Eyes Saddle Creek or the Story Is In The Soil…. -

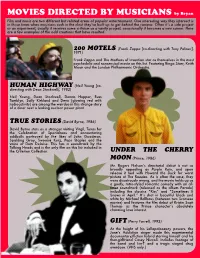

DIRECTED by MUSICIANS by Bryan Film and Music Are Two Different but Related Areas of Popular Entertainment

MOVIES DIRECTED BY MUSICIANS by Bryan Film and music are two different but related areas of popular entertainment. One interesting way they intersect is in those times when musicians cash in the clout theyʼve built up to get behind the camera. Often itʼs a side project or an experiment, usually it receives some criticism as a vanity project, occasionally it becomes a new career. Here are a few examples of the odd creations that have resulted. 200 MOTELS (Frank Zappa [co-directing with Tony Palmer], 1971) Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention star as themselves in the most psychedelic and nonsensical movie on this list. Featuring Ringo Starr, Keith Moon and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. HUMAN HIGHWAY (Neil Young [co- directing with Dean Stockwell], 1982) Neil Young, Dean Stockwell, Dennis Hopper, Russ Tamblyn, Sally Kirkland and Devo (glowing red with radioactivity) are among the weirdos in this strange story of a diner next a leaking nuclear power plant. TRUE STORIES (David Byrne, 1986) David Byrne stars as a stranger visiting Virgil, Texas for the Celebration of Specialness and encountering oddballs portrayed by the likes of John Goodman, Spalding Gray, Swoosie Kurz, Pops Staples and the voice of Dom DeLuise. This has a soundtrack by the Talking Heads and is the only film on this list included in the Criterion Collection. UNDER THE CHERRY MOON (Prince, 1986) Mr. Rogers Nelsonʼs directorial debut is not as broadly appealing as Purple Rain, and upon release it tied with Howard the Duck for worst picture at The Razzies. As is often the case, they were disastrously wrong, and the movie holds up as a goofy, retro-styled romantic comedy with an all- timer soundtrack (released as the album Parade) including the classics “Kiss” and “Sometimes It Snows in April.” Itʼs shot in beautiful black and white by Michael Ballhaus (between two Scorsese movies) and features the film debut of Kristin Scott Thomas as the Prince characterʼs absolutely charming love interest. -

The Cd Central Staff

CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CEN- TRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CEN- TRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CEN- TRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 CD CENTRAL BEST OF 2009 WELL, HELLO! It’s been another fun year at CD Central! Certainly one filled with ups and downs (thinking about the Limestone road project here) but the bottom line is we’ve enjoyed bringing some great music to Lexington, both live and on disc. This booklet is our annual recap of some of the year’s brightest musical highlights. One of the great things we can look back at this year is our participation in Local First Lexington. All of the members of LFL are locally-owned, independent businesses who do great things for our community. These are the businesses that make Lexington a unique place among a sea of national chain stores. Please make it one of your New Year’s resolutions to “Think Local First” when making your buying decisions in the coming year. It feels good to shop local and it makes Lexington a better place. -

Pop and Jazz Across the U.S. This Summer - Nytimes.Com 5/5/11 8:22 PM

Pop and Jazz Across the U.S. This Summer - NYTimes.com 5/5/11 8:22 PM HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Subscribe to The Times Welcome, andreakramer3 Log Out Help Search All NYTimes.com Music WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS ART & DESIGN BOOKS DANCE MOVIES MUSIC TELEVISION THEATER VIDEO GAMES Advertise on NYTimes.com Pop and Jazz Log in to see what your friends Log In With Facebook are sharing on nytimes.com. Privacy Policy | What’s This? What’s Popular Now The Inner Lives Pakistani Army of Wartime Chief Warns U.S. Photographers on Another Raid Richard Termine for The New York Times The cast of “Glee Live!,” whose North American tour begins May 21 in Las Vegas By AMANDA PETRUSICH Published: May 5, 2011 Alabama RECOMMEND TWITTER HANGOUT MUSIC FESTIVAL Blog E-MAIL Gulf Shores, May 20-22. Anyone Advertise on NYTimes.com PRINT ArtsBeat looking to combine two timeless The latest on the REPRINTS arts, coverage of summer pastimes — beach lounging Movies Update E-Mail live events, critical and festivalgoing — will be well SHARE Sign up for the latest movie news and reviews, sent reviews, multimedia every Friday. See Sample extravaganzas and served by the Hangout Music Festival, [email protected] much more. Join the discussion. which sets up on Alabama’s white Change E-mail Address | Privacy Policy More Arts News sand gulf shore for three days each Enlarge This Image summer. A boon for the less rustic http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/08/arts/music/pop-and-jazz-across-the-us-this-summer.html?_r=1 Page 1 of 11 Pop and Jazz Across the U.S. -

Graduate-Dissertations-21

Ph.D. Dissertations in Musicology University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Music 1939 – 2021 Table of Contents Dissertations before 1950 1939 1949 Dissertations from 1950 - 1959 1950 1952 1953 1955 1956 1958 1959 Dissertations from 1960 - 1969 1960 1961 1962 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 Dissertations from 1970 - 1979 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 Dissertations from 1980 - 1989 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 Dissertations from 1990 - 1999 1990 1991 1992 1994 1995 1996 1998 1999 Dissertations from 2000 - 2009 2000 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Dissertations since 2010 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2018 2019 Dissertations since 2020 2020 2021 1939 Peter Sijer Hansen The Life and Works of Dominico Phinot (ca. 1510-ca. 1555) (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1949 Willis Cowan Gates The Literature for Unaccompanied Solo Violin (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Gwynn Spencer McPeek The Windsor Manuscript, British Museum, Egerton 3307 (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Wilton Elman Mason The Lute Music of Sylvius Leopold Weiss (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1950 Delbert Meacham Beswick The Problem of Tonality in Seventeenth-Century Music (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1952 Allen McCain Garrett The Works of William Billings (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Herbert Stanton Livingston The Italian Overture from A. Scarlatti to Mozart (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1953 Almonte Charles Howell, Jr. The French Organ Mass in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (under the direction of Jan Philip Schinhan) 1955 George E. -

Albums from the Flaming Lips and Bobby Avey on Nytimes.Com

HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR U.S. Edition Subscribe: Digital / Home Delivery Log In Register Now Help Search All NYTimes.com Music WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE ART & DESIGN BOOKS DANCE MOVIES MUSIC TELEVISION THEATER VIDEO AUTOSGAMES EVENTS NEW MUSIC Log in to see what your friends are sharing Log In With Facebook Albums from the Flaming Lips and Bobby Avey on nytimes.com. Privacy Policy | What’s Albums from the Flaming Lips and Bobby Avey This? By JON PARELES and BEN RATLIFF What’s Popular Now Published: April 15, 2013 Israel Bombs THE FLAMING LIPS FACEBOOK Syria as the U.S. Weighs Its Own TWITTER Options Enlarge This Image “The Terror” GOOGLE+ In Lean Years After Boom, (Lovely Sorts/ SAVE Spain’s Graft Laid Bare Warner Brothers) E-MAIL SHARE The goofy costumes, flashing lights, confetti blasts and general hilarity of PRINT the Flaming Lips’ concerts largely REPRINTS conceal the sense of dread that has also run through their songs in a recording career that has now lasted Connect With for an improbable 30 years. But Us on Twitter Follow there’s no escaping bleakness on “The @nytimesarts for Terror,” which willfully tosses away nearly anything that arts and entertainment might offer easy pleasure or comic relief. news. Arts Twitter List: Critics, Reporters “The Terror” embraces repetition and abrasiveness more and Editors monolithically than previous Flaming Lips albums. Through three decades Wayne Coyne has led his band on an uncharted trajectory amid punk, psychedelia, studio MOST E-MAILED MOST VIEWED obsessiveness, science fiction, mysticism and noise; Steven 1.