Jazz, and the Principle of Collective Improvisation Margaret E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sidney Bechet Bechet Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sidney Bechet Bechet mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Bechet Country: France Released: 1980 MP3 version RAR size: 1394 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1988 mb WMA version RAR size: 1703 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 790 Other Formats: APE WMA MMF MP2 VOC AAC AU Tracklist Hide Credits Sheik Of Araby A1 2:53 Written-By – Wheeler*, Smith*, Snyder* House Party A2 2:36 Written-By – Mezzrow* Lee Ve Blues A3 2:50 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Wilson* Jam Up A4 4:10 Written-By – Mezzrow* Evil Ball Blues A5 2:58 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Wilson* Where Am I A6 4:35 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Bechet* Funky But A7 4:08 Written-By – Mezzrow* Revolutionnary Blues B1 7:36 Written-By – Mezzrow* Fat Mama Blues B2 3:07 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Wilson* Out Of The Galion B3 2:27 Written-By – Mezzrow* Woop This Wolf Away B4 2:55 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Wilson* Blowin The Blues B5 2:55 Written-By – Mezzrow* Hey Dady Blues B6 2:40 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Wilson* In A Mezz B7 2:55 Written-By – Mezzrow*, Price* Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: SAGEM Related Music albums to Bechet by Sidney Bechet Mezz Mezzrow And His Band With Lee Collins And Zutty Singleton - Mezz Mezzrow And His Band Ladnier . Mezzrow . Bechet - The Panassié Sessions The Mezzrow-Bechet Quintet - The King Jazz Story Vol. 7-8 Mezzrow-Saury Quintet - Mezzrow Saury Quintet - Sweet Sue The Mezzrow-Bechet Quintet With Sammy Price - I'm Speaking My Mind Sidney Bechet, Mezz Mezzrow - Blues With Bechet Mezz Mezzrow And His Swing Band - Lost / A Melody From The Sky Mezz Mezzrow And His Orchestra - "Pleyel Concert" The Mezzrow-Bechet Quintet - Bechet-Mezzrow Quintet Mezzrow - The Cross Of Tormention. -

Whicl-I Band-Probably Sam; Cf

A VERY "KID" HOWARD SUMMARY Reel I--refcyped December 22, 1958 Interviewer: William Russell Also present: Howard's mother, Howard's daughter, parakeets Howard was born April 22, 1908, on Bourbon Street, now renamed Pauger Street. His motTier, Mary Eliza Howard, named him Avery, after his father w'ho di^d in 1944* She sang in church choir/ but not professionally. She says Kid used to beat drum on a box with sticks, when he was about twelve years old. When he was sixteen/ he was a drummer. They lived at 922 St. Philip Street When Kid was young. He has lived around tliere all of his life . Kid's father didn't play a regular instrument, but he used to play on^ a comb, "make-like a. trombone," and he used to dance. Howard's parents went to dances and Tiis mother remembers hearing Sam Morgan's band when she was young, and Manuel Perez and [John] Robichaux . The earliest band Kid remembers is Sam Morgan's. After Sam died, he joined the Morgan band/ witli Isaiah Morgan. He played second trumpet. Then he had his own band » The first instrument he.started on was drums . Before his first marriage, when he got his first drums/ he didn't know how to put them up. He had boughtfhem at Werlein's. He and his first wife had a time trying to put them together * Story about }iis first attempt at the drums (see S . B» Charters): Sam Morgan had the original Sam Morgan Band; Isaiah Morgan had l:J^^i', the Young Morgan Band. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

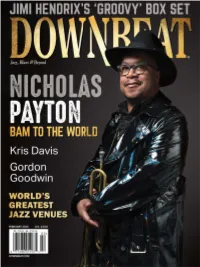

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra with Charlie Parker, Clyde Hart, Slam Stewart, Cozy Cole, Sonny Stitt, Milt Jackson, Al Haig, Thelonious Monk, Sid Catlett, Etc

lonoital Sem.iom 1W! and his Orchestra DIZZIE GILLESPIE CHARLIE PARKER CLYDE HART SLAM STEWART COZY COLE SONNY STITT AL HAIG MILT JACKSON THELONIOUS MONK DAVE BURNS SID CATLETT SAGA6920 L WORLD WIDE 6900 Sidney Bechet Album (Recorded New York SIDE ONE 1945/1947) with Mezz Mezzrow, Hot Lips Page, Will Bill HE BEEPED WHEN HE SHOULD Davidson, etc. HAVE BOPPED (a) GROOVIN' HIGH (b) 0, 6901 Louis Armstrong Volume 1 (Recorded New M York 1938/1947) DIZZY ATMOSPHERE (b) with Jack Teagarden, Bud Freeman, Fats Waller, 00 BOP SH'BAM (c) and his Orchestra Bobby Hackett, etc. OUR DELIGHT (d) 6902 Duke Ellington — His most important Second ✓-SALT PEANUTS (f) War Concert (1943) with Harold Baker, Taft Jordan, Ray Nance, Jimmy Hamilton, etc. SIDE TWO 6903 Count Basie at the Savoy Ballroom (1937) ONE BASS HIT part two (a) In the restless, insecure world of jazz, fashions change with embarr- Despite the scepticism of many of his colleagues, Gillespie and the with Buck Clayton, Ed Lewis, Earl Warren, Lester Young, etc. ALL THE THINGS YOU ARE (b) assing frequency, and reputations wax and wane with the seasons. band, were successful. The trumpeter only stayed for six months, ✓ HOT HOUSE (e) Comparatively few artists have succeeded in gaining universal, con- however, and was soon in the record studios, cutting three of the 6904 Louis Armstrong — Volume 2 (Recorded New THAT'S EARL, BROTHER (c) sistent respect for their musical achievements, and still fewer have tracks on this album, 'Groovin' High', 'Dizzy Atmosphere', and 'All York 1948/1950) with Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney Bigard, THINGS TO COME (a) been able to reap the benefits of this within their own lifetime. -

Because in Church He Would Tell the Brother and Sisters What to Do .. ,;^^

f rt f y * .. 'f v .'. i'..." Presenti ':Ric'hard B- Alleh* 1 (- ^* i. t .'^. FREDDIE MOORE ^ » f I 1 ' ^- -f; .!. * ^ f tl' '- t- 1. r 1 ....-!:£ ^eel I-Summary-Re typed banny Barker f I ''.I ('' * <'! I + s June 19, 1969 f, / t / .i ''. I * ^ * » v I "('.> ^ -rl^ -I r 1 4 I i The tape was recorded at 115 W» 141st Street in tTew Yofk t . / * 4a * I . .'.t City. Fred Moore is called by most of the people Freddie Moore» I ;( i .'} ^ .*. T Freddie was born in Washington, North Carolina which is sometimes .r f '^ 1. 1 ^ -t Ik called "Little Washington," Nortt-i Carolina; Freddie l/s birthday * I J. * ^ i -1 is August 20, approximately 1900; he is fifty-ei^ht years old new. ,-f ^'};' -^ ^ * "; f* . Freddie is the only one in his family who played or sang* Freddi6 ^ :.^ f '':. s. i.' * ;- '".; .» + *. >-. 1 f ; started off wifh mus 1c as a kid with the carnivals and minstrel T?^ Jf f * t. J » '4 * .'V' h *' I f- shows; he was a hamfat dancer, ie* a buck dancejc, DB "sort of a * ^ ^ ' n \-} .< t 1 ', '1. Not a teal skilljsd 1 jive dancer, buck and wing, cut the fool," r ^ ^ t -.1'. -,. Freddie t I, professional dancer, but what ever came into your mind* " -' 'i f ^ I r .S1 t I r 1 was a black-faced comedian* » ( .h + ^ * t .* I- J »^ The first music Freddie remembers hearing was some of Jelly 1^ .; :^ '"^ It- \ + r-»'" A \ I. J Roll Morton s number s» [Obviously DB and RBA doul^t -bliis] < Of I- t. -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

As Fate Would Have It Pat Sajak and Vanna White would have been quite at home in New Orleans in January 1828. It was announced back then in L’Abeille de Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee) that “Malcolm’s Celebrated Wheel of Fortune” was to “be handsomely illuminated this and to-morrow evenings” on Chartres Street “in honour of the occasion”. The occasion was the “Grand Jackson Celebration” where prizes totaling $121,800 were to be awarded. The “Wheel of Fortune” was known as Rota Fortunae in medieval times, and it captured the concept of Fate’s capricious nature. Chaucer employed it in the “Monk’s Tale”, and Dante used it in the “Inferno”. Shakespeare had many references, including “silly Fortune’s wildly spinning wheel” in “Henry V”. And Hamlet had those “slings and arrows” with which to contend. Dame Fortune could indeed be “outrageous”. Rota Fortunae by the Coëtivy Master, 15th century In New Orleans her fickle wheel caused Ignatius Reilly’s “pyloric valve” to close up. John Kennedy Toole’s fictional protagonist sought comfort in “The Consolation of Philosophy” by Boethius, but found none. Boethius wrote, “Are you trying to stay the force of her turning wheel? Ah! Dull-witted mortal, if Fortune begins to stay still, she is no longer Fortune.” Ignatius Reilly found “Consolation” in the “Philosophy” of Boethius. And Boethius had this to say about Dame Fortune: “I know the manifold deceits of that monstrous lady, Fortune; in particular, her fawning friendship with those whom she intends to cheat, until the moment when she unexpectedly abandons them, and leaves them reeling in agony beyond endurance.” Ignatius jotted down his fateful misfortunes in his lined Big Chief tablet adorned with a most impressive figure in full headdress. -

For Additional Information Contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 Or

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. HANK JONES NEA Jazz Master (1989) Interviewee: Hank Jones (July 31, 1918 – May 16, 2010) Interviewer: Bill Brower Date: November 26-27, 2004 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, pp. 134 Hank Jones: I was over there for about two and a half weeks doing a promotional tour. I had done a couple of CDs; one was with my brother Elvin and Richard Davis, the bass player. They made – – I think they made two releases from that date. And I did another date with Jack DeJohnette and John Patitucci. But, these two albums were the objects of the promotion. I mean, they promote very, very heavily everyday. I must have had 40 interviews and about 30 record signings at the record shops, plus all of the recording. We did seven concerts and people inevitably want the records, CDs of the concert for us to sign. I have a trio over there, with Jimmy Cobb and John Fink. It was called, “The Great Jazz Trio.” It was not my name, but the Japanese have special names for everything, you know? That's only one in a series of tree others which he called the great jazz trio. The first one was Ron Carter, Tony Williams and myself. But, there had been a succession of different changes in personnel. It changed about six times. The current one was Jimmy Cobb and Dave Fink--Oh, the cookies have arrived and not a minute too soon. -

Remember Your August the Nineteenth, by The

AL MORGAN Reel X [of 2] August 19, 1958 Also present; William Russell rRussell:1 O.K., I guess it's going if .you want to give your name. You don't have to get close; just sit back and relax. [Morgan: 1 0. K. d' .t [Russell:1 It'll pick up anthing in the room. [M0rqan:1 Well, my name is Al Morgan- [Russell:1 Is [there?] any middle name by the way? [Norcran:1 No, well they-my full name-call me Albert, but I've always-everybody-I went [ j with says ?] they liked Al- [Russell:1 That's right. Th:at's all I ever heard. [Morgan:] For short. (Laughs) ? [Russell:1 [ . .I- ] I didn't know until last night I heard somebody call you Albert. When were you born? Remember your birth date? [Morgan :1 Oh yes, I was born, about forty-two years ago. That's August the nineteenth, by the way, today is my birthday. (Laughs) [Russell:] [ ? ?] Oh my; What a time to hit [ » What was tl-ie year then? Let me see:,, nineteen-- [Morgan:] Oh boy, let me see. We have to go- [Russell:] Porty-two- *t [Morgan:] Back, that should be from now, about- [Russell:1 1916, would that be about- [Morgan:] 19-uh-about 1912- [Russell:] 1912. [ Morgan:1 Something like that. [Russell:1 Yeah, well, anyway- [Morgan:] Just about. Well, it's close. AL MORGAN 2 Reel I [of 2] August 19, 1958 [Russell:] Yeah, do you remember your first music you ever heard when you were a kid? Was it your brothers' playing or [your folks?] [Morq-an:1 Well, yes, I remember lots about my brothers' playing, way before I ever started, you see. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron.