The Caucasus Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume II, Issue 2, March 2021.Pages

INTERNATIONAL COUNTER-TERRORISM REVIEW VOLUME II, ISSUE 2 February, 2021 The Revival of Islam How Do External Factors Shape the Potential Islamist Threat in Azerbaijan? FUAD SHAHBAZOV ABOUT ICTR The International Counter-Terrorism Review (ICTR) aspires to be the world’s leading student publication in Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism Studies. ICTR provides a unique opportunity for students and young professionals to publish their papers, share innovative ideas, and develop an academic career in Counter-Terrorism Studies. The publication also serves as a platform for exchanging research and policy recommendations addressing theoretical, empirical and policy dimensions of international issues pertaining to terrorism, counter-terrorism, insurgency, counter-insurgency, political violence and homeland security. ICTR is a project jointly initiated by the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya, Israel and NextGen 5.0. The International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) is one of the leading academic institutes for counter-terrorism in the world. Founded in 1996, ICT has rapidly evolved into a highly esteemed global hub for counter-terrorism research, policy recommendations and education. The goal of the ICT is to advise decision makers, to initiate applied research and to provide high-level consultation, education and training in order to address terrorism and its effects. NextGen 5.0 is a pioneering non-profit, independent, and virtual think tank committed to inspiring and empowering the next generation of peace and security leaders in order to build a more secure and prosperous world. COPYRIGHT This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Narmina Rustamova Suleyman Rustam 14/23, Baku, Azerbaijan Mobile: (+994) 50 349 47 56 Email: Narmina [email protected]

Narmina Rustamova Suleyman Rustam 14/23, Baku, Azerbaijan Mobile: (+994) 50 349 47 56 email: [email protected] Experience Adjunct Instructor 01/2019 – present ADA University Baku, Azerbaijan Delivering lectures in Health Economics. Adjunct Instructor 01/2016 – 01/2017 ADA University Baku, Azerbaijan Delivered lectures in Quantitative Research Methods, Data Management and Data Analysis. Senior Advisor 01/2011-05/2012 State Committee for Securities of the Republic of Azerbaijan Baku, Azerbaijan Supervised financial intermediaries and lottery operators. Audited and determined risk categories of market participants. Developed legislation on financial markets. Conducted negotiations with international organizations. Adjunct Professor 06/2010-12/2011 Baku State University Baku, Azerbaijan Delivered lectures in Accounting and International Economic Relationships. Developed education programs and examination database. Education PhD in Economics 03/2018 – present Baku State University Baku, Azerbaijan Master of Arts in Economics 07/2008-06/2010 Central European University Budapest, Hungary Bachelor in Economic Cybernetics 09/2004-06/2008 Baku State University Baku, Azerbaijan Professional Developments/Trainings • Participant in the project on “Economic North-Caucasus Federal University diplomacy in the development of Eurasian Pyatigorsk, Russia, 2018 integration” • Participant in the courses for Graduate Studies CERGE-EI in Economics Prague, Czech Republic, 2012 – 2014 • Participant in the seminar on “Tools for onsite Capital Markets -

TIGHTENING the SCREWS Azerbaijan’S Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Plant Expedition to the Republic of Georgia

PLANT EXPEDITION TO THE REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA — CAUCASUS MOUNTAINS AUGUST 15 - SEPTEMBER 11, 2010 SPONSORED BY THE DANIEL F. AND ADA L. RICE FOUNDATION PLANT COLLECTING COLLABORATIVE (PCC) Chicago Botanic Garden Missouri Botanical Garden The Morton Arboretum New York Botanical Garden University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum 1 Table of Contents Summary 3 Georgia’s Caucasus 4-6 Expedition, Expedition Route & Itinerary 7-10 Collaboration 11 Observations 12-13 Documentation 14 Institutional review 14-15 Acknowledgements 16 Maps of the Republic of Georgia and PCC member locations 17 Photo Gallery Collecting 18-19 Collections 20-24 Seed Processing 25 Landscapes 26-29 Transportation 30 Dining 31 People 32-33 Georgia Past and Present 34 Georgia News 35-36 Appendix I – Germplasm Collections Listed by Habit Appendix II – Germplasm Collections Listed Alphabetically Appendix III – Weed Risk Assessment Appendix IV – Field Notes 2 Summary With generous support from the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Foundation, Galen Gates and the Plant Collecting Collaborative (PCC) team made outstanding progress through an expedition in the Republic of Georgia. On this recent trip into the Caucasus Moun- tains, a record was set for the most collections made on any Chicago Botanic Garden and PCC expedition to date. The trip, door to door, was 26 days with field collecting most days; nearly every night‘s activity included seed cleaning. We made three hundred collections at 60 sites. Most were seeds from 246 types of trees, shrubs, and perennials, 14 were bulb taxa and four were in the form of perennial roots. Remarkably, 53 taxa are new to U.S. -

Understanding Russia Better Through Her History: Sevastopol, an Enduring Geostrategic Centre of Gravity

UNDERSTANDING RUSSIA BETTER THROUGH HER HISTORY: SEVASTOPOL, AN ENDURING GEOSTRATEGIC CENTRE OF GRAVITY Recent events in Crimea, Eastern Ukraine and Syria have aerospace industries, made Sevastopol a closed city during brought Russia’s increasingly assertive foreign policy and the Cold War. Thereafter, despite being under Ukrainian burgeoning military power into sharp relief. Such shows of jurisdiction until March 2014, it remained very much a force surprised those in the West who thought that a new, Russian city, in which the Russian national flag always flew pacific and friendly Russia would emerge from the former higher than the Ukrainian. Soviet Union. That has never been Russia’s way as a major Furthermore, the Russian world power. This monograph argues that Vladimir Putin’s Navy continued to control the “” Russia has done no more than act in an historically consistent port leased from the Ukraine, Sevastopol’s and largely predictable manner. Specifically, it seeks to including its navigation systems. population, explain why possession of Sevastopol – the home of the Sevastopol’s population, Black Sea Fleet for more than 200 years – provides Russia containing many military containing many with considerable geostrategic advantage, one that is being retirees and their dependants, military retirees and exploited today in support of her current operations in Syria. remained fiercely loyal to Russia their dependants, and never accepted Ukrainian Sevastopol, and more particularly its ancient predecessor, rule – which they judged as a remained fiercely the former Greek city of Chersonesos, has a highly-symbolic historical accident at best, or, at loyal to Russia and place in Russia’s history and sense of nationhood. -

Odessa : Genius and Death in a City of Dreams Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ODESSA : GENIUS AND DEATH IN A CITY OF DREAMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles King | 336 pages | 20 May 2011 | WW Norton & Co | 9780393070842 | English | New York, United States Odessa : Genius and Death in a City of Dreams PDF Book Other Popular Editions of the Same Title. Great introduction to a city with a very unique history. With more tournament opportunities, which make it possible to earn a living, the number and level of women in chess has really risen in the last twenty years. A diverse mix of nationalities: Armenian, Greek, Turkish, Jewish, Italian and, of course, Russian that mostly lived together in toleration. It built itself as a city of many nationalities and religions and became a place for cultures to merge and clash. Chapter Thirteen War and Nonsense. He thinks Putin is a wise leader, and that Ukraine could use someone like him; he once spent hours explaining to me that Stalin had ingeniously trapped Hitler into invading Russia. And I think I was always fascinated by the idea that people who live as far away as Europe or even in the Soviet Union must be real people, need not have two heads. All there. Marissa's Romance Recommendations! Skip to main content. But then of course the thing being proclaimed in Britain, France, US, or elsewhere is also increasingly 19th century. Convert currency. Italian merchants, Greek freedom fighters, and Turkish seamen; a Russian empress and her favorite soldier-bureaucrats; Jewish tavern keepers, traders, and journalists-these and many others seeking fortune and adventure rubbed shoulders in Odessa, the greatest port on the Black Sea. -

Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology in the Caucasus

-.! r. d, J,,f ssaud Artsus^rNn Mlib scoIuswVC ffiLffi pac,^^€C erplJ pue lr{o) '-I dlllqd ,iq pa11pa ,(8oyoe er4lre Jo ecr] JeJd eq] pue 'sct1t1od 'tustleuolleN 6rl Se]tlJlljd 18q1 uueul lOu soop sltll'slstSo[ocPqJJu ul?lsl?JneJ leool '{uetuJO ezrsuqdtue ol qsl'\\ c'tl'laslno aql 1V cqtJo lr?JttrrJ Suteq e:u e,\\ 3llLl,\\'ieqt 'teqlout? ,{g eldoed .uorsso.rciclns euoJo .:etqSnr:1s louJr crleuols,{s eql ul llnseJ {eru leql tsr:d snolJes uoJl uPlseJnPJ lerll JO suoluolstp :o ..sSutpucJsltu,' "(rolsrqerd '..r8u,pn"r.. roJ EtlotlJr qsllqulso ol ]duralltl 3o elqetclecctl Surqsrn8urlstp o.1". 'speecorcl ll sV 'JB ,(rnluec qlxls-pltu eql ut SutuutSeq'et3:oe9 11^ly 'porred uralse,t\ ut uotJl?ztuolol {eer{) o1 saleleJ I se '{1:clncrlled lBJlsselc uP qil'\\ Alluclrol eq] roJ eJueptlc 1r:crSoloaeqcJe uuts11311l?J Jo uollRnlele -ouoJt-loueqlpue-snseon€JuJequoueqlpuE'l?luoulJv'er8rocg'uelteq -JaZVulpJosejotrolsrqerdsqtJoSuouE}erdlelutSutreptsuoc.,{11euor8ar lsrgSurpeeco:cl'lceistqlsulleJlsnlpselduexalere^esButlele;"{qsnsecne3 reded stql cql ur .{SoloeeqJlu Jo olnlpu lecrllod eql elBltsuotuop [lt,\\ .paluroclduslp lou st euo 'scrlr1od ,(:erodueluoJ o1 polelsJUtr '1tns:nd JturcpeJe olpl ue aq or ,{Soloeuqole 3o ecrlcu'rd eq} lcedxa lou plno'{\ 'SIJIUUOC aAISOldxe ouo 3Jor{,t\ PoJe uP sl 1t 'suolllpuoJ aseql IIe UsAtD sluqle pur: ,{poolq ,{11euor1dacxo lulo^es pue salndstp lelrollrrel snor0tunu qlr,n elalder uot,3e; elllBlo^ ,(re,r. e st 1l 'uolun lel^os JeuIJoJ aql io esdelloc eqt ue,tr.3 'snsBsnBJ aql jo seldoed peu'{u oql lle ro3 ln3Sutueau 'l?Iuusllllu -

Distribution: EG: Bank of Jandara Lake, Bolnisi, Burs

Subgenus Lasius Fabricius, 1804 53. L. (Lasius) alienus (Foerster, 1850) Distribution: E.G.: Bank of Jandara Lake, Bolnisi, Bursachili, Gardabani, Grakali, Gudauri, Gveleti, Igoeti, Iraga, Kasristskali, Kavtiskhevi, Kazbegi, Kazreti, Khrami gorge, Kianeti, Kitsnisi, Kojori, Kvishkheti, Lagodekhi Reserve, Larsi, Lekistskali gorge, Luri, Manglisi, Mleta, Mtskheta, Nichbisi, Pantishara, Pasanauri, Poladauri, Saguramo, Sakavre, Samshvilde, Satskhenhesi, Shavimta, Shulaveri, Sighnaghi, Taribana, Tbilisi (Mushtaidi Garden, Tbilisi Botanical Garden), Tetritskaro, Tkemlovani, Tkviavi, Udabno, Zedazeni (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1964a, b, 1966, 1967b, 1968, 1974a); W.G.: Abasha, Ajishesi, Akhali Atoni, Anaklia, Anaria, Baghdati, Batumi Botanical Garden, Bichvinta Reserve, Bjineti, Chakvi, Chaladidi, Chakvistskali, Eshera, Grigoreti, Ingiri, Inkiti Lake, Kakhaberi, Khobi, Kobuleti, Kutaisi, Lidzava, Menji, Nakalakebi, Natanebi, Ochamchire, Oni, Poti, Senaki, Sokhumi, Sviri, Tsaishi, Tsalenjikha, Tsesi, Zestaponi, Zugdidi Botanical Garden (Ruzsky, 1905; Karavaiev, 1926; Jijilashvili, 1974b); S.G.: Abastumani, Akhalkalaki, Akhaltsikhe, Aspindza, Avralo, Bakuriani, Bogdanovka, Borjomi, Dmanisi, Goderdzi Pass, Gogasheni, Kariani, Khanchali Lake, Ota, Paravani Lake, Sapara, Tabatskuri, Trialeti, Tsalka, Zekari Pass (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1967a, 1974a). 54. L. (Lasius) brunneus (Latreille, 1798) Distribution: E.G.: Bolnisi, Gardabani, Kianeti, Kiketi, Manglisi, Pasanauri (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1968, 1974a); W.G.: Akhali Atoni, Baghdati, -

SHUSHA History, Culture, Arts

SHUSHA History, culture, arts Historical reference: Shusha - (this word means «glassy, transparent») town in the Azerbaijan Republic on the territory of Nagorny Karabakh. Shusha is 403 km away from Baku, it lies 1400 m above the sea levels, on Karabakh mountainous ridge. Shusha is mountainous-climatic recreation place. In 1977 was declared reservation of Azerbaijan architecture and history. Understanding that should Iranian troops and neighbor khans attack, Boy at fortress will not serve as an adequate shelter, Khan transferred his court to Shakhbulag. However, this fortress also could not protect against the enemies. That is why they had to build fortress in the mountains, in impassable, inaccessible place, so that even strong enemy would not be able to take it. The road to the fortress had to be opened from the one side for ilats from the mountains, also communication with magals should not be broken. Those close to Panakh Ali-khan advised to choose safer site for building of a new fortress. Today's Shusha located high in the mountains became that same place chosen by Panakh Ali- khan for his future residence. Construction of Shusha, its palaces and mosques was carried out under the supervision of great poet, diplomat and vizier of Karabakh khanate Molla Panakh Vagif. He chose places for construction of public and religious buildings (not only for Khan but also for feudal lords-»beys»). Thus, the plans for construction and laying out of Shusha were prepared. At the end of 1750 Panakh Ali-khan moved all reyats, noble families, clerks and some senior people from villages from Shakhbulag to Shusha. -

The Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813 and the Treaty of Gulistan in the Context of Its 200Th Anniversary)

Volume 7 Issue 3-4 2013 141 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Ganja showed that the Georgian state played the main role on the anti-Seljuk front in the Caucasus and that, despite the crippling Seljuk inroads, it remained the leading political force in the Caucasus. Conclusion My analysis of the sources and historiography, as well as my interpretation of what was hap- pening on the Byzantine-Seljuk front on the eve of the battle of Manzikert, provide a fairly plausible explanation of why the otherwise belligerent sultan retreated from his previously confrontational policy toward the audacious Georgian king. In the late 1060s, when Bagrat IV carried out his offensive operations in Eastern Georgia, which directly infringed on the military and political interests of the Seljuk sultan, the latter was tied down by preparations for the final offensive on the Byzantine Empire. He had to show caution when dealing with Bagrat IV, a potential ally of Byzantium. There is every reason to believe that his unexpectedly friendly gesture, instead of a punitive expedition, was caused by his desire to keep Georgia away from an imminent global clash with Byzantium. Oleg KUZNETSOV Ph.D. (Hist.), Deputy Rector for Research, Higher School of Social and Managerial Consulting (Institute) (Moscow, the Russian Federation). THE TREATY OF GULISTAN: 200 YEARS AFTER (THE RUSSO-PERSIAN WAR OF 1804-1813 AND THE TREATY OF GULISTAN IN THE CONTEXT OF ITS 200TH ANNIVERSARY) Abstract he author looks at the causes and some sus, which went down to history as the of the aspects and repercussions of Great Game or the Tournament of Shad- T the Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813 ows. -

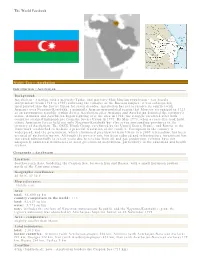

The World Factbook Middle East :: Azerbaijan Introduction

The World Factbook Middle East :: Azerbaijan Introduction :: Azerbaijan Background: Azerbaijan - a nation with a majority-Turkic and majority-Shia Muslim population - was briefly independent (from 1918 to 1920) following the collapse of the Russian Empire; it was subsequently incorporated into the Soviet Union for seven decades. Azerbaijan has yet to resolve its conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, a primarily Armenian-populated region that Moscow recognized in 1923 as an autonomous republic within Soviet Azerbaijan after Armenia and Azerbaijan disputed the territory's status. Armenia and Azerbaijan began fighting over the area in 1988; the struggle escalated after both countries attained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. By May 1994, when a cease-fire took hold, ethnic Armenian forces held not only Nagorno-Karabakh but also seven surrounding provinces in the territory of Azerbaijan. The OSCE Minsk Group, co-chaired by the United States, France, and Russia, is the framework established to mediate a peaceful resolution of the conflict. Corruption in the country is widespread, and the government, which eliminated presidential term limits in a 2009 referendum, has been accused of authoritarianism. Although the poverty rate has been reduced and infrastructure investment has increased substantially in recent years due to revenue from oil and gas production, reforms have not adequately addressed weaknesses in most government institutions, particularly in the education and health sectors. Geography :: Azerbaijan Location: Southwestern