T06-00020-V10-N02-88

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2019 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Hi Blues Fans, The final ballots for the 2019 WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Best of the Blues (“BB Awards”) Proud Recipient of a 2009 of the Washington Blues Society are due in to us by April 9th! You Keeping the Blues Alive Award can mail them in, email them OFFICERS from the email address associ- President, Tony Frederickson [email protected] ated with your membership, or maybe even better yet, turn Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected] them in at the April Blues Bash Secretary, Open [email protected] (Remember it’s free!) at Collec- Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected] tor’s Choice in Snohomish! This Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected] is one of the perks of Washing- ton Blues Society membership. DIRECTORS You get to express your opinion Music Director, Amy Sassenberg [email protected] on the Best of the Blues Awards Membership, Open [email protected] nomination and voting ballots! Education, Open [email protected] Please make plans to attend the Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected] BB Awards show and after party Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected] this month. Your Music Director Amy Sassenburg and Vice President Advertising, Open [email protected] Rick Bowen are busy working behind the scenes putting the show to- gether. I have heard some of their ideas and it will be a stellar show and THANKS TO THE WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY 2017 STREET TEAM exceptional party! True Tone Audio will provide state-of-the-art sound, Downtown Seattle, Tim & Michelle -

NEW MEMBERS of the SENATE 1968-Present (By District, with Prior Service: *House, **Senate)

NEW MEMBERS OF THE SENATE 1968-Present (By District, With Prior Service: *House, **Senate) According to Article III, Section 15(a) of the Constitution of the State of Florida, Senators shall be elected for terms of 4 years. This followed the 1968 Special Session held for the revision of the Constitution. Organization Session, 1968 Total Membership=48, New Members=11 6th * W. E. Bishop (D) 15th * C. Welborn Daniel (D) 7th Bob Saunders (D) 17th * John L. Ducker (R) 10th * Dan Scarborough (D) 27th Alan Trask (D) 11th C. W. “Bill” Beaufort (D) 45th * Kenneth M. Myers (D) 13th J. H. Williams (D) 14th * Frederick B. Karl (D) Regular Session, 1969 Total Membership=48, New Members=0 Regular Session, 1970 Total Membership=48, New Members=1 24th David H. McClain (R) Organization Session, 1970 Total Membership=48, New Members=9 2nd W. D. Childers (D) 33rd Philip D. “Phil” Lewis (D) 8th * Lew Brantley (D) 34th Tom Johnson (R) 9th * Lynwood Arnold (D) 43rd * Gerald A. Lewis (D) 19th * John T. Ware (R) 48th * Robert Graham (D) 28th * Bob Brannen (D) Regular Session, 1972 Total Membership=48, New Members=1 28th Curtis Peterson (D) The 1972 election followed legislative reapportionment, where the membership changed from 48 members to 40 members; even numbered districts elected to 2-year terms, odd-numbered districts elected to 4-year terms. Organization Session, 1972 Redistricting Total Membership=40, New Members=16 2nd James A. Johnston (D) 26th * Russell E. Sykes (R) 9th Bruce A. Smathers (D) 32nd * William G. Zinkil, Sr., (D) 10th * William M. -

PABL003 Tampa Red Front.Std

c TAM PA RED c PABL003 PABL003 THE M AN W ITH THE GOLD GUITAR TTaammppaa / She's Love Crazy (3:00) 24/6/41 @ Love With A Feeling (2:58) 16/6/38 RReedd 0 Delta Woman Blues (3:07) 11/10/37 A Travel On (2:24) 11/10/37 1 Bessemer Blues (2:48) 15/5/39 B Deceitful Friend Blues (3:02) 11/10/37 2 It's A Low Down Shame (2:57) 24/6/41 C When The One You Love Is Gone (3:08) 4/5/37 3 Hard Road Blues (2:57) 27/11/40 D It Hurts Me Too (2:32) 10/5/40 4 So Far, So Good (2:43) 24/6/41 E Witchin' Hour Blues (3:13) 27/10/34 5 You Missed A Good Man (3:34) 1/11/35 F Grievin' And Worryin' Blues (3:05) 14/6/34 6 Anna Lou Blues (2:53) 10/5/40 G Let Me Play With Your Poodle (2:39) 6/2/42 7 Got To Leave My Woman (3:19) 14/3/38 H She Wants To Sell My Monkey (3:20) 6/2/42 ? Kingfish Blues (3:08) 22/3/34 I Why Should I Care? (3:26) 14/3/38 All songs written and performed by Tampa Red (vocals, guitar, electric guitar, piano, kazoo) with Carl Martin (guitar, 17), Henry Scott (guitar, 16), Black Bob (guitar, 7, 10, 11?) Willie B. James (guitar, 2, 12, 13, 14, 20), Blind John Davis (piano, 3, 8, 15), Ransom Knowling (bass, 1, 3, 4, 6) Big Maceo Merriweather (piano, 1, 4, 6, 18, 19), Clifford 'Snags' Jones (drums, 18, 19), and others TThhee MM aann All recorded in Chicago except tracks 2, 9, 11, 12, 14, 20, Aurora, Illinois Restoration and XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, January 2008 WW iitthh TThhee Cover artwork based on photographs of Tampa Red Total duration: 60:13 ©2008 Pristine Audio. -

Florida Women's Heritage Trail Sites 26 Florida "Firsts'' 28 the Florida Women's Club Movement 29 Acknowledgements 32

A Florida Heritag I fii 11 :i rafiM H rtiS ^^I^H ^bIh^^^^^^^Ji ^I^^Bfi^^ Florida Association of Museums The Florida raises the visibility of muse- Women 's ums in the state and serves as Heritage Trail a liaison between museums ^ was pro- and government. '/"'^Vm duced in FAM is managed by a board of cooperation directors elected by the mem- with the bership, which is representa- Florida tive of the spectrum of mu- Association seum disciplines in Florida. of Museums FAM has succeeded in provid- (FAM). The ing numerous economic, Florida educational and informational Association of Museums is a benefits for its members. nonprofit corporation, estab- lished for educational pur- Florida Association of poses. It provides continuing Museums education and networking Post Office Box 10951 opportunities for museum Tallahassee, Florida 32302-2951 professionals, improves the Phone: (850) 222-6028 level of professionalism within FAX: (850) 222-6112 the museum community, www.flamuseums.org Contact the Florida Associa- serves as a resource for infor- tion of Museums for a compli- mation Florida's on museums. mentary copy of "See The World!" Credits Author: Nina McGuire The section on Florida Women's Clubs (pages 29 to 31) is derived from the National Register of Historic Places nomination prepared by DeLand historian Sidney Johnston. Graphic Design: Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Digital Media, Tallahassee. Special thanks to Ann Kozeliski, A Kozeliski Design, Tallahassee, and Steve Little, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee. Photography: Ray Stanyard, Tallahassee; Michael Zimny and Phillip M. Pollock, Division of Historical Resources; Pat Canova and Lucy Beebe/ Silver Image; Jim Stokes; Historic Tours of America, Inc., Key West; The Key West Chamber of Commerce; Jacksonville Planning and Development Department; Historic Pensacola Preservation Board. -

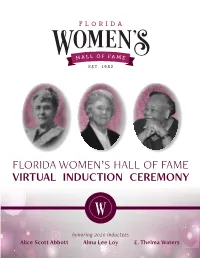

The 2020 Induction Ceremony Program Is Available Here

FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME VIRTUAL INDUCTION CEREMONY honoring 2020 inductees Alice Scott Abbott Alma Lee Loy E. Thelma Waters Virtual INDUCTION 2020 CEREMONY ORDER OF THE PROGRAM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women CONGRATULATORY REMARKS Jeanette Núñez . Florida Lieutenant Governor Ashley Moody . Florida Attorney General Jimmy Patronis . Florida Chief Financial Officer Nikki Fried . Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Charles T. Canady . Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice ABOUT WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME & KIOSK Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee 2020 FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME INDUCTIONS Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee HONORING: Alice Scott Abbott . Accepted by Kim Medley Alma Lee Loy . Accepted by Robyn Guy E. Thelma Waters . Accepted by E. Thelma Waters CLOSING REMARKS Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women 2020 Commissioners Maruchi Azorin, M.B.A., Tampa Rita M. Barreto, Palm Beach Gardens Melanie Parrish Bonanno, Dover Madelyn E. Butler, M.D., Tampa Jennifer Houghton Canady, Lakeland Anne Corcoran, Tampa Lori Day, St. Johns Denise Dell-Powell, Orlando Sophia Eccleston, Wellington Candace D. Falsetto, Coral Gables Rep. Heather Fitzenhagen, Ft. Myers Senator Gayle Harrell, Stuart Karin Hoffman, Lighthouse Point Carol Schubert Kuntz, Winter Park Wenda Lewis, Gainesville Roxey Nelson, St. Petersburg Rosie Paulsen, Tampa Cara C. Perry, Palm City Rep. Jenna Persons, Ft. Myers Rachel Saunders Plakon, Lake Mary Marilyn Stout, Cape Coral Lady Dhyana Ziegler, DCJ, Ph.D., Tallahassee Commission Staff Kelly S. Sciba, APR, Executive Director Rebecca Lynn, Public Information and Events Coordinator Kimberly S. -

ELECTRIC BLUES the DEFINITIVE COLLECTION Ebenfalls Erhältlich Mit Englischen Begleittexten: BCD 16921 CP • BCD 16922 CP • BCD 16923 CP • BCD 16924 CP

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] PLUG IT IN! TURN IT UP! ELECTRICELECTRIC BBLUESLUES DAS STANDARDWERK G Die bislang umfassendste Geschichte des elektrischen Blues auf insgesamt 12 CDs. G Annähernd fünfzehneinhalb Stunden elektrisch verstärkte Bluessounds aus annähernd siebzig Jahren von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart. G Zusammengestellt und kommentiert vom anerkannten Bluesexeperten Bill Dahl. G Jede 3-CD-Ausgabe kommt mit einem ca. 160-seitigen Booklet mit Musikerbiografien, Illustrationen und seltenen Fotos. G Die Aufnahmen stammen aus den Archiven der bedeutendsten Plattenfirmen und sind nicht auf den Katalog eines bestimmten Label beschränkt. G VonT-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Ray Charles und Freddie, B.B. und Albert King bis zu Jeff Beck, Fleetwood Mac, Charlie Musselwhite, Ronnie Earl und Stevie Ray Vaughan. INFORMATIONEN Mit insgesamt annähernd dreihundert Einzeltiteln beschreibt der Blueshistoriker und Musikwissenschaftler Bill Dahl aus Chicago die bislang umfassendste Geschichte des elektrischen Blues von seinen Anfängen in den späten 1930er Jahren bis in das aktuelle Jahrtausend. Bevor in den Dreißigerjahren Tonabnehmersysteme, erste primitive Verstärker und Beschallungssysteme und schließ- lich mit Gibsons ES-150 ein elektrisches Gitarren-Serienmodell entwickelt wurde, spielte die erste Generation der Gitarrenpioniere im Blues in den beiden Jahrzehnten vor Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkriegs auf akustischen Instrumenten. Doch erst mit Hilfe der elektrischen Verstärkung konnten sich Gitarristen und Mundharmonikaspielern gegenüber den Pianisten, Schlagzeugern und Bläsern in ihrer Band behaupten, wenn sie für ihre musikalischen Höhenflüge bei einem Solo abheben wollten. Auf zwölf randvollen CDs, jeweils in einem Dreier-Set in geschmackvollen und vielfach aufklappbaren Digipacks, hat Bill Dahl die wichtigsten und etliche nahezu in Vergessenheit geratene Beispiele für die bedeutendste Epoche in der Geschichte des Blues zusammengestellt. -

J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board J. William

J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 16-22186 FFSB-report-2015_PRINTcover.indd 2 09/09/2016 7:45 AM Front Cover: M Jackson at Svínafellsjökull, Iceland, on her 2015-2016 Fulbright-National Science Foundation Arctic Research grant: “Glacier retreat happens not just at the glacier margin, or on the top, but also worryingly within the very heart of the ice. Glaciers are our most visible evidence of climatic changes, and they often remind me of our collective vulnerability on this blue blue planet.” Jackson’s doctoral research at the University of Oregon centers on understanding how glaciers matter to people on the south coast of Iceland, and what it is that humanity stands to lose as the planet’s glaciers disappear. “It is critical that we understand how today’s rapidly changing glaciated environments impact surrounding communities, which requires extensive, long-term fieldwork in remote places. I am grateful that Fulbright has continually supported me in this work, from my first Fulbright grant in Turkey, where I taught at Ondokuz Mayis University and researched glaciers and people in the Kaçkar Mountains, to my current research in Iceland. Without Fulbright, I would not be able to do Photo by Eli Weiss this research.” (Photo by Eric Kruszewski) 16-22186 FFSB-report-2015_PRINTcover.indd 3 09/09/2016 7:45 AM (From left) U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs Evan Ryan, National Science Foundation Arctic Science Section Head Eric Saltzman, Iceland Fulbright Commission Executive Director Belin- da Theriault, and Iceland‘s Ambassa- dor to the United States Geir Haarde at the signing of the Fulbright-Nation- al Science Foundation agreement on January 21, 2015, for a groundbreak- ing partnership to fund grants for U.S. -

Sylvia Rodriguez Kimbell and Patricia Doby, Registered Nurse Clinician

Hillsborough County Women’s Hall of Fame Charter Class Induction Ceremony COMMISSION ON THE Status Women Mayof 26, 2011 The Hillsborough County Women's Hall of Fame was created by the Hillsborough County Commission on the Status of Women Agenda to honor women who, through their lives and efforts, have made significant contributions to the improvement of life for women and for all citizens Reception of Hillsborough County. The Commission maintains and facilitates Welcome the permanent Women's Hall of Fame display. Yvonne Fry, Commission Chair Blessing Purpose of COSW The Commission is comprised of thirteen members. Dotti Groover-Skipper, Commission Vice Chair Seven are appointed by members of the Board of County Commissioners to represent their district, Induction Ceremony and six are permanent seats held by Hillsborough County Yvonne Fry organizations. INDUCTEE PRESENTER Susan Sharp appointed by Commissioner Sandra L. Murman Laura Rambeau-Lee appointed by Commissioner Victor D. Crist Mary T. Cash Commissioner Sandra L. Murman Ann Porter appointed by Commissioner Lesley “Les” Miller, Jr. Betty Castor Commissioner Al Higginbotham Yvonne Fry appointed by Commissioner Al Higginbotham, Chair Helen Gordon Davis Commissioner Lesley “Les” Miller, Jr. Dotti Groover-Skipper appointed by Commissioner Ken Hagan, Vice Chair Cecile Waterman Essrig Commissioner Ken Hagan Yvonne McDonald appointed by Commissioner Kevin Beckner Pat Collier Frank Commissioner Kevin Beckner Susan Leisner appointed by Commissioner Mark Sharpe Sandra W. Freedman Mayor Bob Buckhorn Caroline Murphy The Centre Clara C. Frye Commissioner Mark Sharpe April Monteith Greater Tampa Chamber of Commerce Adela Hernandez Gonzmart Commissioner Victor D. Crist Lydia Medrano, Ph.D. Hispanic Professional Women’s Association, Inc. -

The Yazoo Review. Hopefully, You Will Find a Combination of Indepth Reviews As Well As Great Prices for Purchasing Albums, Cassettes, Compact Discs, Videos, Books

The Y a z o o R eview Hello, Welcome to our first issue of The Yazoo Review. Hopefully, you will find a combination of indepth reviews as well as great prices for purchasing albums, cassettes, compact discs, videos, books. This first issue is to give you a taste of things to come. We do not intend to be a source for ALL blues albums. There are just too many available. But rather we will offer the cream of the crop and keep you abreast of new and exciting releases. Our initial complete listing has over 500 albums. We have highlighted various artists and subjects in the Review and these articles should give you information and a feel for each album. We have gathered some of the finest writers in blues music to contribute their ideas and insights. Chris Smith, Neil Slaven and Ray Templeton are three of the most respected names in blues critique. After each introductory paragraph to a subject you will find the author’s name. He has written all the reviews in that area unless another writer’s name is included. Our prices are the lowest available especially when taking advantage of our SPECIAL OFFER. You can choose ANY four albums or cassettes and purchase a fifth for $1.95. A similar offer applies to compact discs but in this case the fifth CD would cost $3.95. You can mix CD’s/cassettes and albums for your four albums and in this case the fifth must be an album or cassette for $1.95. You can order as many albums as you wish. -

FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities Florida Humanities

University of South Florida Scholar Commons FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities Florida Humanities 1-1-1996 Forum : Vol. 18, No. 03 (Winter : 1995/1996) Florida Humanities Council. Nancy F. Cott Linda Vance Doris Weatherford Nancy A. Hewitt See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/forum_magazine Recommended Citation Florida Humanities Council.; Cott, Nancy F.; Vance, Linda; Weatherford, Doris; Hewitt, Nancy A.; Vickers, Sally; McGovern, James R.; Dughi, Donn; and Ridings, Dorothy S., "Forum : Vol. 18, No. 03 (Winter : 1995/ 1996)" (1996). FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities. 60. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/forum_magazine/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Florida Humanities at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Florida Humanities Council., Nancy F. Cott, Linda Vance, Doris Weatherford, Nancy A. Hewitt, Sally Vickers, James R. McGovern, Donn Dughi, and Dorothy S. Ridings This article is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/forum_magazine/60 WINTER 1995/1996 The Magazine of the FIo.ida Humanities Council FROM TO WOMEN AND P01111 RTICIATION 1900-1982 FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FLORIDA HUMANITIES For Women, Two Paths COUNCIL to Political Action BOARD OF DIRECTORS LESTER ABBERGER MERCY DIAZ-MIRANDA Tallahassee Miami ELAINET. AZEN WILLIAM T. HALL, JR. hen I moved to Florida ten years ago, I began to hear about an Fort Lauderdale Niceville organization that reminded me of another generation, the League BETTIE BARKDULL THOMAS J. -

9-16-21-Deluca Auction

SPECIAL John Tefteller’s World’s Rarest Records AUCTION AUCTION! Address: P. O. Box 1727, Grants Pass, OR 97528-0200 USA #1 Phone: (541) 476–1326 or (800) 955–1326 • FAX: (541) 476–3523 Ralph DeLuca’s E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.tefteller.com More DeLuca Pre-War auctions to Blues Auction closes Thursday, September 16, 2021 at 7:00 p.m. come! Presenting . The Ralph DeLuca Collection of Pre-War Blues 78’s! This is auction #1 (of at least five) of the record Mr. DeLuca has moved into the art world, collection. Be prepared though — the great stuff is collection of Ralph DeLuca. no longer collecting 78’s, as he finds it easier to going to go for a lot of money! buy rare art than rare records. That should tell Mr. DeLuca is most known for his legendary you something! E+ is the highest grade used. This is the old-time collection of rare movie posters, but for about 15 78 grading system and I am very strict. years he actively, and aggressively, collected rare There should be something for each and every Blues 78’s, mostly Pre-War. Blues collector reading this auction. There are The next Ralph DeLuca auction will be in a few titles here not seen for sale in decades . and months and contains another 100 goodies. He plunged into collecting rare Blues 78’s hot some may never be seen again. and heavy and went for the best whenever and Good luck to all! wherever he could find them. He bought smart This is your chance to get some LEGENDARY and paid big to get what he wanted! rarities and just plain GREAT records for your THE 3 KINGS OF THE BLUES! CHARLEY PATTON TOMMY JOHNSON ROBERT JOHNSON 1. -

Final Agenda 2005.Vp

S T A T E O F F L O R I D A CHARLIE CRIST ATTORNEY GENERAL Dear Friends and Colleagues: Welcome to the 20th National Conference on Preventing Crime in the Black Community. Our co-sponsors, along with the many local host agencies and organizations in the Tampa area, have teamed up with my staff for what I think you will find to be both an educational and enjoyable week. We are encouraged that each year we join with new allies and partners in our fight against crime and violence in our communities. In 2005 the conference will mark a milestone, the celebration of its 20th consecutive year. As those of you who have joined us on this journey well know, it has taken hard work, though it has been a labor of love, in order for this conference to become a unique and respected national crime prevention annual event. Thank you for your continued commitment, support, and resources to these vital prevention efforts. As Florida’s Attorney General, I am both pleased and honored to sponsor this important initiative. Sincerely, Charlie Crist 20th National Conference on Preventing Crime in the Black Community 1 Departjment of Law State of Georgia THURBERT E. BAKER 40 CAPITOL SQUARE SW ATTORNEY GENERAL ATLANTA, GA 30334-1300 Dear Friends: Allow me to extend my greetings and personal best wishes to you as we kick off the National Conference on Preventing Crime in the Black Community. As we gather this summer in Tampa, it is my fervent hope that we will continue the tremendous work of previous conferences, and I truly believe that this, our 20th conference, will be our most productive conference yet.