'Conceiving Jesus: Re-Examining Jesus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walking Dead

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1080950 Filing date: 09/10/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91217941 Party Plaintiff Robert Kirkman, LLC Correspondence JAMES D WEINBERGER Address FROSS ZELNICK LEHRMAN & ZISSU PC 151 WEST 42ND STREET, 17TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10036 UNITED STATES Primary Email: [email protected] 212-813-5900 Submission Plaintiff's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name James D. Weinberger Filer's email [email protected] Signature /s/ James D. Weinberger Date 09/10/2020 Attachments F3676523.PDF(42071 bytes ) F3678658.PDF(2906955 bytes ) F3678659.PDF(5795279 bytes ) F3678660.PDF(4906991 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Cons. Opp. and Canc. Nos. 91217941 (parent), 91217992, 91218267, 91222005, Opposer, 91222719, 91227277, 91233571, 91233806, 91240356, 92068261 and 92068613 -against- PHILLIP THEODOROU and ANNA THEODOROU, Applicants. ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Opposer, -against- STEVEN THEODOROU and PHILLIP THEODOROU, Applicants. OPPOSER’S NOTICE OF RELIANCE ON INTERNET DOCUMENTS Opposer Robert Kirkman, LLC (“Opposer”) hereby makes of record and notifies Applicant- Registrant of its reliance on the following internet documents submitted pursuant to Rule 2.122(e) of the Trademark Rules of Practice, 37 C.F.R. § 2.122(e), TBMP § 704.08(b), and Fed. R. Evid. 401, and authenticated pursuant to Fed. -

Event RECAP July 21-23 Wired Café San Diego, CA July 21-23 July 21-23 2011 WIRED Café

EVENT RECAP JULY 21-23 WIRED CAFÉ SAN DIEGO, CA JULY 21-23 JULY 21-23 2011 WIRED CAFÉ From July 21-23, 2011, WIRED hosted the 3rd Annual WIRED Café @ Comic-Con. Throughout the weekend, over 3,000 guests received invitation-only access to WIRED’s full-service Café, which provided a media preview lounge, gadget lab, cuisine, cocktails, and a host of activities and interactive demos from WIRED partners, including HBO, Microsoft, History Channel, MGM Casinos, Budweiser Select, and Pringles. An all-star cast of celebs stopped by to sample the food, drinks, and gear, including Justin Timberlake, Amanda Seyfried, Jon Favreau, Rose McGowan, Natasha Henstridge, Olivia Munn, John Landis, Adam West, Billy Dee Williams, Kevin Smith, Nikki Reed, Kellan Lutz, and the entire cast of HBO’s True Blood. All of these celebs were captured by the WIRED.com video crew and featured on WIRED.com. Both Access Hollywood and CNN camped out all day to interview the stars of True Blood. PRESENTED BY SPONSORED BY WIRED CAFÉ SAN DIEGO, CA JULY 21-23 SAN DIEGO, CA JULY 21-23 WIRED CAFÉ 5 “I love the WIRED Café, it’s one of my favorite spots at Comic-Con.” —Kellan Lutz KellanWIRED Lutz CAF/ TwilightÉ SAN DIEGO, CA JULY 21-23 SAN DIEGO, CA JULY 21-23 WIRED CAFÉ 7 Lucy LawlessWIRED CAF /É SpartacusSAN DIEGO, CA JULY 21-23 JULY 21-23 CELEBRITY ATTENDEES 6 / 7 / 8 / 1 / 9 / 10 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 11 / 12 / 1 / Justin Timberlake and Amanda Seyfried, In Time 2 / Rose McGowan, Conan the Barbarian 3 / Rutina Wesley, True Blood 6 / Eric Balfour, Haven 7 / Aisha Tyler, Archer 8 / Nikki Reed, Twilight 9 / Jon Favreau, Cowboys and Aliens 4 / Skyler Samuels, The Nine Lives of Chloe King 5 / Tony Hale, Alan Tudyk, Adam Brody, and Jake Busey, Good Vibes 10 / Dominic Monaghan, X-Men Origins: Wolverine 11 / Kristin Bauer and Alexander Skarsgard, True Blood 12 / Kevin Smith, 4.3.2.1. -

1 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY of CONGRESS

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Under 17 U.S.C. §1201 Docket No. 2014-07 Reply Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Mitchell L. Stoltz Corynne McSherry Kit Walsh Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of rightsholders and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while promoting innovation, freedom of speech, and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these reply comments, EFF represents the interests of the many people in the U.S. who have “jailbroken” their cellular phone handsets and other mobile computing devices—or would like to do so—in order to use lawfully obtained software of their own choosing, and to remove software from the devices. 2. Proposed Class 16: Jailbreaking – wireless telephone handsets Computer programs that enable mobile telephone handsets to execute lawfully obtained software, where circumvention is accomplished for the sole purposes of enabling interoperability of such software with computer programs on the device or removing software from the device. 1 3. -

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist www.juliacarta.com PRESS JUNKETS/PUBLICITY EVENTS Matt Dillon - Grooming - WAYWARD PINES - London Press Junket Jeremy Priven - Grooming - BAFTA Awards - London Christian Bale - Grooming - AMERICAN HUSTLE - BAFTA Awards - London Naveen Andrews - Grooming - DIANA - London Press Junket Bruce Willis and Helen Mirren - Grooming - RED 2 - London Press Conference Ben Affleck - Grooming - ARGO - Sebastián Film Festival Press Junket Matthew Morrison - Grooming - WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOU’RE EXPECTING - London Press Junket Clark Gregg - Grooming - THE AVENGERS - London Press Junket Max Iron - Grooming - RED RIDING HOOD - London Press Junket and Premiere Mia Wasikowska - Hair - RESTLESS - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Elle Fanning - Make-Up - SUPER 8 - London Press Junket Jamie Chung - Hair & Make-Up - SUCKERPUNCH - London Press Junket and Premiere Steve Carell - Grooming - DESPICABLE ME - London Press Junket and Premiere Mark Strong and Matthew Macfayden - Grooming - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Michael C. Hall - Grooming - DEXTER - London Press Junket Jonah Hill - Grooming - GET HIM TO THE GREEK - London Press Junket and Premiere Laura Linney - Hair and Make-Up - THE BIG C - London Press Junket Ben Affleck - Grooming - THE TOWN - London and Dublin Press and Premiere Tour Andrew Lincoln - Grooming - THE WALKING DEAD - London Press Junket Rhys Ifans - Grooming - NANNY MCPHEE: THE BIG BANG (RETURNS) - London Press Junket and Premiere Bruce Willis - Grooming - RED - London -

The Walking Dead: Volume 26: Call to Arms Free Ebook

FREETHE WALKING DEAD: VOLUME 26: CALL TO ARMS EBOOK Charlie Adlard,Stefano Gaudiano,Robert Kirkman | 136 pages | 20 Sep 2016 | Image Comics | 9781632159175 | English | Fullerton, United States The Walking Dead AMC's The Walking Dead is one of the most popular shows on TV, but we bet you didn't know these 5 surprising facts about the series. Full of great characters, flesh-craving zombies, and tales of fighting for survival, it’s no surprise that AMC’s The Walking Dead has developed a huge cult following. A few years ago it seemed that The Walking Dead would outlive us all—but on Wednesday Scott Gimple and Angela Kang confirmed that the onetime TV juggernaut will come to an end with a episode 11th season. Once upon a time, The Walking Dead was planned to run for 12 seasons at least. Over the years. The Walking Dead is a cultural phenomenon and as such has a lot of games made about it. This game though is going to get you up close and personal in VR. Check out The Walking Dead: Onslaught Verizon BOGO Alert! Get two Galaxy S20+ for $15/mo with a new Unlimited line We may earn a commission for pu. The Worst Characters on ‘The Walking Dead’ Rick and his group of survivors have been through a lot, and not just with the walkers. There are terrible humans out there, some trying to take and control what they shouldn't. So who from the action-packed world of the "Walking Dead" are you? ENTERTAINMENT By: Khadija Leon 5 Min Quiz Rick and his. -

Andrew Lincoln

VAT No. 993 055 789 ANDREW LINCOLN TRAINING: ROYAL ACADEMY OF DRAMATIC ART FILM: Made in Dagenham Mr Clarke Number 9 Films Nigel Cole Heartbreaker Jonathan Focus Features Pascal Chaumeil Scenes of a Sexual Jamie Tin Pan Films Edward Blum Nature Comme t'y es Belle! Paul Future Films Lisa Azuelos These Foolish Things Christopher Lovell 111 Pictures Julia Taylor-Stanley Enduring Love TV Producer Pathe Roger Michell Love Actually Mark Working Title Richard Curtis Offending Angels Sam Pants Productions Andrew Rajan Gangster NO. 1 Maxie King Film Four Paul McGuigan Human Traffic Felix Fruit Salad Films Justin Kerrigan Boston Kick Out Ted Boston Films Justin Kerrigan TELEVISION: The Walking Dead Rick Valhala Motion Pictures Fran Darabont Strike Back Hugh Collinson Left Bank Pictures Various Wuthering Heights Edgar Linton Mammoth Screen Coky Geidrroyc Moonshot Michael Collins Dangerous Films Richard Dale Lukas Reiter Project Joe NBC Productions Barry Sonnenfield This Life - 10 Years Egg World Productions Joe Ahern After Life Robert Bridge Clerkenwell Films Various Whose Baby? Barry Flint ITV Rebecca Frayn Lie With Me DI Will Tomlinson Granada Susanna White Teachers Simon Casey Channel 4 Various Canterbury Tales: Alan King BBC Julian Jarrold The Man Of Law's Tale State of Mind Julian Latimer Monogram Productions Christopher Menaul A Likeness to Stone Richard Kirschman Bbc Charles Beeson Bomber Capt. Willy Byrne Zenith David Drury Woman in White Walter Hartwright Bbc Tim Fywell This Life Egg World Productions Various Bramwell Martin Fredericks -

P20-22 Layout 1

20 Established 1961 Wednesday, July 25 , 2018 Lifestyle Music & Movies Gloria Estefan awarded Spain’s gold medal for the arts loria Estefan, the Cuban-American pop Speaking to reporters afterwards, the multi- released in January: “We have re-invented some star who achieved worldwide fame in Grammy Award winner, who has had hits in of my tracks so you can consider it a ‘Greatest Gthe 1980s, was honoured by the Spanish Spanish and English, spoke out on some of the hits’ so to speak, but no, because it also has four government on Monday for her contribution to issues facing Latino people in the United States, new tracks.”— Reuters the arts. Accompanied by her music-producer including the policy of separating the children of husband Emilio, the singer was presented with migrants from their parents. the Gold Medal of Merit for the Arts by Culture “We are frightened about the treatment Cuban-US singer Gloria Estefan (center) poses Minister Jose Guirao in Madrid’s Teatro Real those children received,” Estefan told a news with Spanish Culture and Sports Minister Jose opera house. The ceremony was organized conference. “It’s a very difficult moment and I Guirao (left) and her husband Emilio Estefan especially for Estefan, who could not attend an think the whole of the United States is a bit anx- after receiving Spain’s Gold Medal of Merit in event earlier this year where King Felipe pre- ious. It’s a difficult time worldwide.” Estefan said the Fine Arts during a ceremony at the Teatro sented medals to several other recipients. -

Paleyfest Featuring 'The Walking Dead

February 7, 2013 "PaleyFest Featuring ‘The Walking Dead' and ‘The Big Bang Theory'" Events Broadcast to U.S. Cinemas This March NCM® Fathom Events and The Paley Center for Media Present "PaleyFest Featuring ‘The Walking Dead'" on Thursday, March 7 and "PaleyFest Featuring ‘The Big Bang Theory'" on Wednesday, March 13 in Select Movie Theaters Nationwide Movie Theater Audiences Will Have Opportunity to Submit Questions to "The Big Bang Theory" Cast LIVE via Twitter LOS ANGELES & CENTENNIAL, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- For the first time ever, the stars and producers of the phenomenally successful "The Walking Dead" and No. 1 comedy series "The Big Bang Theory" are coming to theaters nationwide as part of the ultimate TV fan festival — PaleyFest (The William S. Paley Television Festival). Presented by NCM® Fathom Events and The Paley Center for Media in celebration of PaleyFest's 30th anniversary, "PaleyFest" will feature a lively panel discussion from these sold-out events, giving audiences an exclusive look inside these TV hits. "PaleyFest Featuring ‘The Walking Dead,'" the festival's opening night presentation, pre-recorded March 1 featuring appearances by the cast and creative team, will be broadcast to select U.S. movie theaters on Thursday, March 7 at 8:00 p.m. local time."PaleyFest Featuring ‘The Big Bang Theory,'" broadcast LIVE from the Saban Theatre in Beverly Hills, Calif., on Wednesday, March 13 at 10:00 p.m. ET / 9:00 p.m. CT / 8:00 p.m. MT / 7:00 p.m. PT, will feature a live and uncensored Q&A with the cast and producers of TV's most-watched comedy. -

Actor Alicia Witt Turns Musician with 'Revisionary History'

ALICIA WITT Alicia Witt has had an over three-decade long career, starting with her acting debut as Alia in David Lynch's classic ‘Dune’. Alicia received rave reviews for her role as Paula in Season 6 of AMC’s critically acclaimed series The Walking Dead. Witt also appeared during Season 4 of ABC’s ‘Nashville’ as country star Autumn Chase and in the new Twin Peaks on Showtime, reprising her role as Gerstein Hayward. Witt most recently was seen haunting John Cho’s character as Demon Nikki on Season 2 of Fox’s The Exorcist; other recent credits include the Emmy-award winning Showtime series ‘House of Lies’ opposite Don Cheadle and the hit WB series ‘Supernatural’. Witt is also well known to Hallmark audiences for her annual Christmas movies; her latest, which she co-wrote and is producing, will be released later this year. She can also be seen this fall as Marjorie Cameron in Season 2 of anthology series Lore, on Amazon. In 2014, Alicia joined the 5th Season of Emmy-award winning FX series ‘Justified’ with Timothy Olyphant. Alicia played Wendy Crowe, the smart and sexy paralegal sister of crime lord Daryl Crowe (Michael Rapaport) who takes matters into her own hands to bring him to justice in the Season 5 finale. On stage, she most recently appeared at the Geffen Playhouse in the Los Angeles debut of Tony-nominated Neil Labute play ‘reasons to be pretty’. In 2013, Alicia appeared opposite Peter Bogdanovich and Cheryl Hines in the independent family dramedy 'Cold Turkey', in a performance which NY Daily News critic David Edelstein hailed as one of the best of 2013. -

Andrew Lincoln, Ed., William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience

REVIEW Andrew Lincoln, ed., William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience Irene Tayler Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 26, Issue 2, Fall 1992, p. 57 Fall 1992 BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY 57 5 Dan Miller, "Blake and the Deconstruc- 6 Robert N. Essick, William Blake and 8 See, for example, Gerald Graff, Litera tive Interlude," in Critical Paths: Blake and the Language of Adam (Oxford: Claren- ture Against Itself: Literary Ideas in the Argument of Method, ed. Donald Ault don, 1989) 97-103, 150, 195-96, 208-10. Modern Society (Chicago: University of et al. (Durham, N.C.: Duke University 7 Blake, letter to George Cumberland, 12 Chicago Press, 1979); and Frederick Press, 1987) 156. April 1827, E 783. Crews, SkepticalEngagements(New York: Oxford University Press, 1986). finished copies we have. Each of the William Blake. Songs of In 54 plates not only has all the usual attractions of Blake's hand-colored nocence and of Exper Songs, but here he also surrounded ience: Shewing the Two each plate with a delicate water color Contrary States of the border that in each case bears themati- Human Soul. Edited with cally on the content of the plate itself. an Introduction and Notes Several of these borders are extremely by Andrew Lincoln. Prince- complex in design and richly colored, ton: The William Blake as in the case of the combined tide- page, which is wreathed in thorns and Trust/Princeton University flames and half-animate leaf-life. Press, 1991.209 pp. $59.50. Others (like those for "The Blossom" of Innocence and "London" of Exper ience) are restrained and monochro- Reviewed by Irene Tayler matic, as if to suggest that in such strong encounters with the life and death of the spirit, further "decoration" could only detract. -

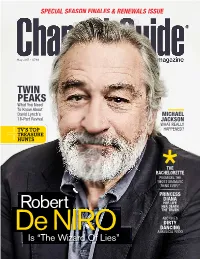

TWIN PEAKS What You Need to Know About David Lynch’S MICHAEL

Time-Sensitive SPECIAL SEASON FINALES & RENEWALS ISSUE PERIODICALS Channel Guide Class Publication Postmaster please deliver by the 1st of the month NAT magazine May 2017 • $7.99 TWIN PEAKS What You Need To Know About David Lynch’s MICHAEL channelguidemag.com 18-Part Revival JACKSON WHAT REALLY TV’S TOP HAPPENED? TREASURE HUNTS PREMIERING 5/9 ON DEMAND THE BACHELORETTE PROMISES THE “MOST DRAMATIC THING EVER!” PRINCESS DIANA HER LIFE HER DEATH Robert THE TRUTH ABC GIVES May 2017 May DIRTY DANCING De NIRO A MUSICAL REDO Is “The Wizard Of Lies” WATCH THE 10 MINUTE FREE PREVIEW SHORT LIST For More ReMIND magazine SEASON offers fresh takes on FINALE popular entertainment DATES We Break Down The Month’s See Page 8 from days gone by. Biggest And Best Programming So Each issue has dozens May You Never Miss A Must-See Minute. of brain-teasing 1 16 23 puzzles, trivia quizzes, Lucifer, FOX — New Episodes NCIS, CBS — Season Finale classic comics and Taken, NBC — Season Finale NCIS: New Orleans, CBS — Season Finale features from the 2 NBA: Western Conference Finals, The Mick, FOX — Season Finale Game 1, ESPN 1950s-1980s! Victorian Slum House, PBS Tracy Morgan: Staying Alive, N e t fl i x — New Series American Epic, PBS — New Series 17 < 5 Downward Dog, ABC — New Series Blue Bloods, CBS — Season Finale Downward Dog, ABC — Sneak Peek Bull, CBS — Season Finale The Mars Generation, N e t fl i x Criminal Minds: Beyond Borders, CBS The Flash, The CW — Season Finale Sense8, N e t fl i x — New Episodes — Season Finale NBA: Eastern Conference Finals, Brooklyn -

Contemporary Spirituality and Study of the Bible: Introducing a Relationship

Transmission Spring 2014 Contemporary Spirituality and Study of the Bible: Introducing a Relationship It is in one sense yesterday’s news that so many people a distinct academic discipline and as a sub-discipline wish to identify themselves as ‘spiritual but not religious’. in other fields suggests that there is more to talk of This phenomenon, however, continues, to dominate spirituality than simply a feel-good Esperanto that the current scene, as the recent report from the Theos could be shared by anyone. Major books and series think tank and the media company CTVC, entitled have been published,2 academic journals in the field ‘The Spirit of Things Unseen’, confirmed.1 It found that have proliferated,3 universities and colleges offer both despite the decline of formalised religious belief and modules and whole degree courses in Spirituality, and institutionalised religious belonging over recent decades, new academic societies have been created.4 a spiritual current runs as powerfully, if not more so, It should occasion no particular surprise or worry that in Andrew through the nation as it ever did. A post-religious nation, such academic discussion ‘spirituality’ remains a slippery the report concluded, is by no means a post-spiritual one. Lincoln term whose definition is debated. The same is true when Andrew Lincoln Any introduction to the relation between this broad and it comes to defining what constitutes a religion. What, continues as hugely contested area of contemporary spirituality and then, do the more serious writers on the subject, whose Professor of New the equally large and complex entity of study of the concern goes beyond such matters as the use of crystals Testament in the University of Bible is bound to be inadequate at best.