Rev Iss Web Icad 12167 9-4 302..319

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topic Paper Chilterns Beechwoods

. O O o . 0 O . 0 . O Shoping growth in Docorum Appendices for Topic Paper for the Chilterns Beechwoods SAC A summary/overview of available evidence BOROUGH Dacorum Local Plan (2020-2038) Emerging Strategy for Growth COUNCIL November 2020 Appendices Natural England reports 5 Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation 6 Appendix 1: Citation for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation (SAC) 7 Appendix 2: Chilterns Beechwoods SAC Features Matrix 9 Appendix 3: European Site Conservation Objectives for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation Site Code: UK0012724 11 Appendix 4: Site Improvement Plan for Chilterns Beechwoods SAC, 2015 13 Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 27 Appendix 5: Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI citation 28 Appendix 6: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 31 Appendix 7: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 33 Appendix 8: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Ashridge Commons and Woods, SSSI, Hertfordshire/Buckinghamshire 38 Appendix 9: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Ashridge Commons and Woods Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003 40 Tring Woodlands SSSI 44 Appendix 10: Tring Woodlands SSSI citation 45 Appendix 11: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 48 Appendix 12: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 51 Appendix 13: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Tring Woodlands SSSI 53 Appendix 14: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Tring Woodlands Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Working Today for Nature Tomorrow

Report Number 693 Knepp Castle Estate baseline ecological survey English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Number 693 Knepp Castle Estate baseline ecological survey Theresa E. Greenaway Record Centre Survey Unit Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Woods Mill, Henfield West Sussex RH14 0UE You may reproduce as many additional copies of this report as you like for non-commercial purposes, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with English Nature, Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA. However, if you wish to use all or part of this report for commercial purposes, including publishing, you will need to apply for a licence by contacting the Enquiry Service at the above address. Please note this report may also contain third party copyright material. ISSN 0967-876X © Copyright English Nature 2006 Cover note Project officer Dr Keith Kirby, Terrestrial Wildlife Team e-mail [email protected] Contractor(s) Theresa E. Greenaway Record Centre Survey Unit Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Woods Mill, Henfield West Sussex RH14 0UE The views in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of English Nature This report should be cited as: GREENAWAY, T.E. 2006. Knepp Castle Estate baseline ecological survey. English Nature Research Reports, No. 693. Preface Using grazing animals as a management tool is widespread across the UK. However allowing a mixture of large herbivores to roam freely with minimal intervention and outside the constraints of livestock production systems in order to replicate a more natural, pre- industrial, ecosystem is not as commonplace. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 29 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fibiger Michael, Sammut Paul M., Seguna Anthony, Catania Aldo Artikel/Article: Recent records of Noctuidae from Malta, with five species new to the European fauna, and a new subspecies 193-213 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Notalepid. 29(3/4): 193-213 193 Recent records of Noctuidae from Malta, with five species new to the European fauna, and a new subspecies Michael Fibiger Paul Sammut-, Anthony Seguna \ & Aldo Catania^ ' Molbecha Allé 49, 4180 Sor0, Denmark; e-mail: [email protected] 2 137, 'Fawkner/2\ Dingli Rd., Rabat, RBT 07, Malta; e-mail: [email protected] ^ 'Redeemer', Triq 1-Emigrant, Naxxar, Malta; e-mail: [email protected] ^ 'Rama Rama', Triq Möns. Anton Cilia, Zebbug, Malta; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Recent records of Noctuoidea from Malta are given. Five noctuid species are recorded from Europe for the first time: Eublemma conistrota Hampson, 1910, Eiiblemma deserti Rothschild, 1909, Anumeta hilgerti (Rothschild 1909), Hadiila deserticula (Hampson 1905), and Eiixoa canariensis Rebel, 1902. New synonyms are stated: Leptosia velocissima f. tarda Turati, 1926, syn. n. and Leptosia griseimargo Warren, 1912, syn. n., both synonyms of Metachrostis velox (Hübner, 1813); and Pseudohadena (Eremohadena) roseonitens espugnensis Lajonquiere, 1964, syn. n., a synonym of P. (E.) roseonitens roseonitens (Oberthür, 1887). A new subspecies of Xylena exsoleta (Linneaus, 1758), Xylena exsoleta maltensis ssp. n., is established. The literature on Maltese Noctuoidea is reviewed and erronuousely reported species are indicated. -

E-Acta Natzralia Pannonica

e ● Acta Naturalia Pannonica e–Acta Nat. Pannon. 5: 39–46. (2013) 39 Hungarian Eupitheciini studies (No. 2) Records from Nattán’s collection (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) Imre Fazekas Abstract: Data on 37 species collected in Hungary are given. Additional data on faunistics, taxonomy and zoogeography of cer- tain species are provided by the author, with comments. Figures of the genitalia of some species are included. With 18 figures. Key words: Lepidoptera, Geometridae, Euptheciini, distribution, biology, Hungary. Author’s address: Imre Fazekas, Regiograf Institute, Majális tér 17/A, H-7300 Komló, Hungary. Introduction A detailed account of the Eupitheciini species in 20% KOH solution. Genitalia were cleaned and Hungary has been given in five previous works dehydrated in ethanol and mounted in Euparal (Fazekas 1977ab, 1979ab, 1980, 2012). To date 64 between microscope slides and cover slips. Illus- Hungarian Geometridae, tribus Eupitheciini are trations of adults were produced by a multi-layer known. technique using a Sony DSC HX100V with a 4x Present paper contains faunistical data of the Macro Conversion Lens. The photographs were Eupitheciini specimens in the Nattán collection (in processed by the software Photoshop CS3 version. coll. Janus Pannonius Museum, H-Pécs) that col- The genitalia illustrations were produced in a sim- lected outside of the South Transdanubia. ilar manner with multi-layer technique, using an- Miklós Nattán (1910–1970) was an amateur lep- other digital camera (BMS tCam 3,0 MP) and a idopterist who, over nearly six decades, made one XSP-151-T-LED Microscope with a plan lens 4/0.1 of the most significant private collections of Lepi- and 10/0.25. -

Local Nature Reserve Management Plan 2020 – 2024

Bisley Road Cemetery, Stroud Local Nature Reserve Management Plan 2020 – 2024 Prepared for Stroud Town Council CONTENTS 1 VISION STATEMENT 2 POLICY STATEMENTS 3 GENERAL DESCRIPTION 3.1 General background information 3.1.1 Location and site boundaries Map 1 Site Location 3.1.2 Tenure Map 2 Schedule Plan 3.1.3 Management/organisational infrastructure 3.1.4 Site infrastructure 3.1.5 Map coverage 3.2 Environmental information 3.2.1 Physical 3.2.2 Biological 3.2.2.1 Habitats Map 3 Compartment Map – Old Cemetery Map 4 Compartment Map – New Cemetery 3.2.2.2 Flora 3.2.2.3 Fauna 3.3 Cultural 3.3.1 Past land use 3.3.2 Present land use 3.3.3 Past management for nature conservation 3.3.4 Present legal status 4 NATURE CONSERVATION FEATURES OF INTEREST 4.1 Identification and confirmation of conservation features 4.2 Objectives 4.2.1 Unimproved grassland 4.2.1.1 Summary description 4.2.1.2 Management objectives 4.2.1.3 Performance indicators 4.2.1.4 Conservation status 4.2.1.5 Rationale 4.2.1.6 Management projects 4.2.2 Trees and Woodland 4.2.2.1 Summary description 4.2.2.2 Management objectives 4.2.2.3 Performance indicators 4.2.2.4 Conservation status 4.2.2.5 Rationale 4.2.2.6 Management projects 4.2.3 Lichens 4.2.3.1 Summary description 4.2.3.2 Management objectives 4.2.3.3 Performance indicators 4.2.3.4 Conservation status 4.2.3.5 Rationale 4.2.3.6 Management projects 4.3 Rationale & Proposals per compartment Bisley Rd Cemetery Mgmt Plan 2020-2024 2 5 HISTORIC INTEREST 5.1 Confirmation of conservation features 5.2 Objectives 5.3 Rationale 6 STAKEHOLDERS 6.1 Evaluation 6.2 Management projects 7 ACCESS / TOURISM 7.1 Evaluation 7.2 Management objectives 8 INTERPRETATION 8.1 Evaluation 8.2 Management Projects 9 OPERATIONAL OBJECTIVES 9.1 Operational objectives 9.2 Management projects 10 WORK PLAN Appendix 1 Species List Bisley Rd Cemetery Mgmt Plan 2020-2024 3 1 VISION STATEMENT Stroud Town Council are committed to conserving Stroud Cemetery to: • Enable the people of Stroud to always have a place of peace and quiet reflection and recreation. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Forsthaus Prösa“

Heideprojekt im NSG „Forsthaus Prösa“ - Schmetterlingsmonitoring - Fotos: I. Rödel Rangsdorf, Januar 2011 Heideprojekt im NSG „Forsthaus Prösa“ - Schmetterlingsmonitoring - Auftraggeber : NaturSchutzFonds Brandenburg Lennéstraße 74 14471 Potsdam Bearbeitung : Natur & Text in Brandenburg GmbH Friedensallee 21 15834 Rangsdorf Tel. 033708 / 20431 [email protected] Dipl. Ing. Ingolf Rödel Rangsdorf, 28. Januar 2011 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Anlass und Aufgabenstellung 1 2 Schmetterlinge als Bioindikatoren zur naturschutzfachlichen Beurteilung von Heidebiotopen 1 3 Kenntnisstand über die Schmetterlingsfauna märkischer Heidegebiete 2 4 Methodik 3 4.1 Spezifische Anforderungen 3 4.2 Erfassungsmethode 3 4.3 Termine 4 4.4 Probeflächen 7 5 Ergebnisse 8 5.1 Gesamtergebnis der Bestandsaufnahmen 8 5.2 Die nachgewiesenen Heideschmetterlinge 9 5.2.1 Dyscia fagaria (Heidekraut-Fleckenspanner) 9 5.2.2 Xestia agathina (Heidekraut Bodeneule) 10 5.2.3 Lycophotia molothina (Graue Heidekrauteule) 11 5.2.4 Dicallomera fascelina (Ginster-Streckfuß) 12 5.2.5 Plebeius argus (Argus-Bläuling) und Plebeius idas (Ginster-Bläuling) 13 5.2.6 Rhagades pruni (Heide-Grünwidderchen) 14 5.2.7 Rhyparia purpurata (Purpurbär) 15 5.2.8 Saturnia pavonia (Kleines Nachtpfauenauge) 15 5.2.9 Lycophotia porphyrea (Porphyr-Eule) 17 5.2.10 Xestia castanea (Ginsterheiden-Bodeneule) 17 5.2.11 Anarta myrtilli (Heidekrauteulchen) 18 5.2.12 Clorissa viridata (Steppenheiden-Grünspanner) 19 5.2.13 Eupithecia nanata (Heidekraut-Blütenspanner) 19 5.2.14 Pachycnemia hippocastanaria (Schmalflügeliger -

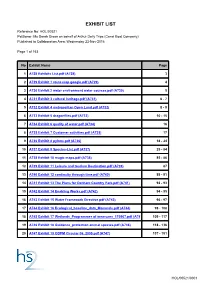

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

E-News Spring 2019

Spring e-newsletter March 2019 Welcome to Spring! Green Hairstreak - Iain Leach Orange-tip - Iain Leach Garden Tiger caterpillar - Roy Leverton INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Contributions to our newsletters Dates for your Diary……………………….2 The Wish List…………………….…13-14 are always welcome. Borders News...........................................3 Our Conservation Strategy…….….15-20 Please use the contact details Munching Caterpillars Scotland.…………4 Carrion Beetles…………….……….21-22 below to get in touch! Peatlands for People………..…………….5 Moth Equipment - for sale...............23 If you do not wish to receive our Recording butterflies using Apps………...6 SW Branch Events 2019……….....24-25 newsletter in the future, simply Adopt a Transect………………………......7 Highland Branch Events 2019..….26-29 reply to this message with the Rare migrant on Islay!..............................8 East Branch Events 2019..….…...30-34 word ’unsubscribe’ in the title - Coul Links Update……………………….9-10 thank you. Northern Brown Argus, Kincraig………11-12 Contact Details: Butterfly Conservation Scotland t: 01786 447753 Balallan House e: [email protected] Allan Park w: www.butterfly-conservation.org/scotland Stirling FK8 2QG Dates for your Diary Wildlife Recorders’ Gathering - Saturday 30th March 10.30 - 4.30pm - Dumfries An informal day of talks, presentations, networking and displays covering the wonderful wildlife of SW Scotland. Contact SWSEIC at [email protected] for more details. Highland Branch AGM - Saturday, 13th April 2019 Our Highlands & Island Branch will be holding their AGM on Saturday, 13th April at the Kingsview Christian Centre, Balnafettack Road, Inverness, IV3 8TF. See Highland Branch Events (Page 27) for more info. South & West Branch Members’ Day/AGM - Saturday, 27th April 2019 Our Glasgow & Southwest Branch will be holding their Members’ Day/AGM on Saturday, 27th April at Chatelherault Country Park. -

Occurrence of Helotropha Leucostigma Hübner (Lep., Noctuidae) on Maize in Rzeszów Region

PROGRESS IN PLANT PROTECTION/POSTĘPY W OCHRONIE ROŚLIN 53 (1) 2013 Occurrence of Helotropha leucostigma Hübner (Lep., Noctuidae) on maize in Rzeszów region Występowanie Helotropha leucostigma Hübner (Lep., Noctuidae) na kukurydzy w okolicach Rzeszowa Paweł K. Bereś1, Tomasz Konefał2 Summary Caterpillars of Helotropha leucostigma Hübner were found for the first time on maize plants (Zea mays L.) in Rzeszów region (south-east Poland) in 2008. In 2008–2012, every year in May and June a small number of caterpillars of this species were recorded on the maize fields, where they totally destroyed single plants at the stage of 4 to 6 leaves (BBCH 14–16). During the study years totaly 30 caterpillars of this species were found in four villages: Krzeczowice, Terliczka, Nienadówka and Głuchów. So far H. leucostigma has not been regarded as a pest of cultivated plants in Poland. The fact that during a few years the caterpillars of this moth were recorded in maize crops may indicate that the species H. leucostigma has adapted to feeding on maize and therefore extended the range of its host plants. Key words: Helotropha leucostigma, Zea mays, Poland, first record Streszczenie Gąsienice Helotropha leucostigma Hübner po raz pierwszy zostały stwierdzone na roślinach kukurydzy (Zea mays L.) w okolicach Rzeszowa (południowo-wschodnia Polska) w 2008 roku. W latach 2008–2012 corocznie, w okresie maja i czerwca obserwowano występowanie nielicznych gąsienic tego gatunku na polach kukurydzy, które całkowicie niszczyły pojedyncze rośliny w fazie od 4 do 6 liści (BBCH 14–16). Łącznie, w latach badań, w czterech miejscowościach: Krzeczowice, Terliczka, Nienadówka oraz Głuchów stwierdzono obecność 30 gąsienic tego gatunku. -

Biodiversity Information Report 13/07/2018

Biodiversity Information Report 13/07/2018 MBB reference: 2614-ARUP Site: Land near Hermitage Green Merseyside BioBank, The Local Biodiversity Estate Barn, Court Hey Park Roby Road, Liverpool Records Centre L16 3NA for North Merseyside Tel: 0151 737 4150 [email protected] Your Ref: None supplied MBB Ref: 2614-ARUP Date: 13/07/2018 Your contact: Amy Martin MBB Contact: Ben Deed Merseyside BioBank biodiversity information report These are the results of your data request relating to an area at Land near Hermitage Green defined by a buffer of 2000 metres around a site described by a boundary you supplied to us (at SJ598944). You have been supplied with the following: records of protected taxa that intersect the search area records of BAP taxa that intersect the search area records of Red Listed taxa that intersect the search area records of other ‘notable’ taxa that intersect the search area records of WCA schedule 9 taxa (including ‘invasive plants’) that intersect the search area a map showing the location of monad and tetrad references that overlap the search area a list of all designated sites that intersect your search area citations, where available, for intersecting Local Wildlife Sites a list of other sites of interest (e.g. Ancient Woodlands) that intersect your search area a map showing such sites a list of all BAP habitats which intersect the search area a map showing BAP habitats a summary of the area for all available mapped Phase 1 and/or NVC habitats found within 500m of your site a map showing such habitats Merseyside BioBank (MBB) is the Local Environmental Records Centre (LERC) for North Merseyside.