386-Santa Maria Ad Martyres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Twenty-Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

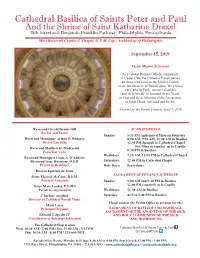

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul And the Shrine of Saint Katharine Drexel 18th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Most Reverend Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap., Archbishop of Philadelphia September 15, 2019 Parish Mission Statement As a vibrant Roman Catholic community in Center City, the Cathedral Parish Serves all those who come to the Mother Church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. We profess our Catholic Faith, minister to others and welcome all, as founded on the Word of God and the celebration of the Sacraments of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Adopted by the Parish Council, April 5, 2016 Reverend Gerald Dennis Gill MASS SCHEDULE Rector and Pastor Sunday: 5:15 PM Anticipated Mass on Saturday Reverend Monsignor Arthur E. Rodgers 8:00 AM, 9:30 AM, 11:00 AM in Basilica Rector Emeritus 12:30 PM Spanish in Cathedral Chapel Sta. Misa en español, en la Capilla Reverend Matthew K. Biedrzycki 6:30 PM in Basilica Parochial Vicar Weekdays: 7:15 AM, 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Monsignor Louis A. D’Addezio Saturdays: 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Isaac Haywiser, O.S.B. Priests in Residence Holy Days: See website Deacon Epifanio de Jesus SACRAMENT OF PENANCE SCHEDULE Sister Eleanor McCann, R.S.M. Pastoral Associate Sunday: 9:00 AM and 5:30 PM in Basilica 12:00 PM (español) en la Capilla Sister Mary Luchia, P.V.M.I Parish Evangelization Weekdays: 11:30 AM in Basilica Charlene Angelini Saturday: 4:15 to 5:00 PM in Basilica Director of Cathedral Parish Music Please contact the Parish Office to arrange for the: Mark Loria SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM AND MARRIAGE, Principal Organist SACRAMENT OF THE ANOINTING OF THE SICK, Edward J. -

EGYPT in ROME (AND BEYOND) JC Zietsman University Of

ACTA CLASSICA LII (2009) 1-21 ISSN 0065-1141 CHAIRPERSON’S ADDRESS • VOORSITTERSREDE CROSSING THE ROMAN FRONTIER: EGYPT IN ROME (AND BEYOND) J.C. Zietsman University of the Free State ABSTRACT A coin issued by Octavian in 27 BC, when he became the Emperor Augustus, pro- claims AEGYPTO CAPTA, ‘Egypt has been captured.’ In actual fact Egyptian culture, architecture, art and religion crossed the Roman frontier and captured the imagination of the Roman world. Apart from Greece, no other country had greater influence over the Romans. The most distinctive evidence of Egyptian presence in Rome is the obelisks. Several of the obelisks exalted the military victories of the pharaohs to whom they were originally dedicated. The Roman emperors, as rulers of Egypt, identified with this use for their own imperialistic and propagandistic purposes. This article will look at the afterlife of some of the most famous obelisks in and beyond the Eternal City after the fall of Rome. Introduction In 264 BC Rome became involved in the First Punic War against Carthage. By the end of this war (241 BC) the Romans found themselves in possession of Sicily, which became the first Roman province. The Third Punic War ended in 146 BC, when the defeated Carthaginian territory became the pro- vince of Africa. Macedonia and Achaea became Roman provinces in the same year. Cunliffe argues that ‘the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean did not lead to a confrontation with Egypt, although the internal quarrels among the mem- bers of the Egyptian dynasty did give Rome some say in the internal matters of Egypt.1 Under the Ptolemies economic and political decay had set in and by the time that Egypt was drawn into the Roman political arena in the second half of the first century BC, the country was in a state of near collapse.’ 1 Cunliffe 1978:232. -

Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri: Incisioni E Scritti Del ‘Cavalier Del Buon Gusto’

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI PISA FACOLTA’ DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA Scuola di Dottorato in Storia delle Arti Visive e dello Spettacolo TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA (L-ART/02; L-ART/04) Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri: incisioni e scritti del ‘Cavalier del Buon Gusto’ CANDIDATA TUTOR Dott.ssa Martina Nastasi Chiar.mo prof. Vincenzo Farinella COORDINATORE DEL DOTTORATO Chiar.ma prof.ssa Cinzia Maria Sicca Bursill-Hall Ciclo dottorato XXIII 0 1 INDICE INTRODUZIONE _______________________________________________________ p. 4 I CAPITOLO. «IL CAVALIER DEL BUON GUSTO» ______________________________ p. 8 I.1 «Non sine labore»: genesi di un’idea di arte ________________________________ p. 8 I.2 Le Vite di pittori ___________________________________________________ p. 31 II CAPITOLO. «PER CAMMINARE CON TUTTA SINCERITÀ E CHIAREZZA»: CATALOGHI DELLA COLLEZIONE GABBURRI _________________________________________________ p. 41 II.1 La collezione di grafica: pratiche di acquisto e scelte di «finissimo gusto» _______ p. 41 II.2 Nuovi cataloghi della collezione Gabburri ______________________________ p. 60 II.3 Analisi del Catalogo di disegni e stampe ___________________________________ p. 66 III CAPITOLO. TRA COLLEZIONISMO E BIOGRAFISMO _________________________ p. 78 III.1 «Per maggior comodo dei dilettanti»: stampe e biografie a servizio dei lettori ___ p. 78 III.2 «Commodità veramente singularissima»: la stampa di traduzione ____________ p. 89 III.3 Donne «virtuose» e «spiritosissime»: attenzione per l’arte al femminile ________ p. 99 TAVOLE _____________________________________________________________ p. 108 APPENDICE DOCUMENTARIA ____________________________________________ p. 124 - Catalogo di stampe e disegni (Fondation Custodia-Institut Néerlandais Parigi, Collection Frits Lugt, P. I, Inv.2005-A.687.B.1, cc. 65-134v) __________________________________________________ p. 126 - Appunti sullo stato dell’arte fiorentina (Fondation Custodia-Institut Néerlandais Parigi, Collection Frits Lugt, P.II, Inv. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

Star Polyhedra: from St Mark's Basilica in Venice To

STAR POLYHEDRA: FROM ST MARK’S BASILICA IN VENICE TO HUNGARIAN PROTESTANT CHURCHES Tibor TARNAI János KRÄHLING Sándor KABAI Full Professor Associate Professor Manager BUTE BUTE UNICONSTANT Co. Budapest, HUNGARY Budapest, HUNGARY Budapest, HUNGARY Summary Star polyhedra appear on some baroque churches in Rome to represent papal heraldic symbols, and on the top of protestant churches in Hungary to represent the Star of Bethlehem. These star polyhedra occur in many different shapes. In this paper, we will provide a morphological overview of these star polyhedra, and we will reconstruct them by using the program package Mathematica 6. Keywords : Star polyhedra; structural morphology; stellation; elevation; renaissance; baroque architecture; protestant churches; spire stars; Mathematica 6.0. 1. Introduction Star is an ancient symbol that was important already for the Egyptians. Its geometrical representation has been a planar star polygon or a polygramma. In reliefs, they have got certain spatial character, but still they remained 2-dimensional objects. Real 3-dimensional representations of stars are star polyhedra. They are obtained by extending the faces of convex polyhedra so that their planes intersect again [1]. This technique is called stellation . In a broader sense, those polyhedra are also called star polyhedra that are obtained by elevating the face centres of the polyhedra, which are, in this way, augmented by pyramids (the base of a pyramid is identical to the face of the polyhedron on which it stands). To our knowledge, star polyhedra do not occur in European culture until the Renaissance. The first example of a star polyhedron is a planar projection of a small stellated dodecahedron in the pavement mosaic of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice ( Fig. -

Grabmalskultur Und Soziale Strategien Im Frühneuzeitlichen Rom Am Beispiel Der Familie Papst Urbans VIII

Grabmalskultur und soziale Strategien im frühneuzeitlichen Rom am Beispiel der Familie Papst Urbans VIII. Barberini Autor(en): Köchli, Ulrich Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Kirchengeschichte = Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique suisse Band (Jahr): 97 (2003) PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-130330 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Grabmalskultur und soziale Strategien im frühneuzeitlichen Rom am Beispiel der Familie Papst Urbans Vili. Barberini Ulrich Köchli Wer je die römische Petersbasilika mit offenen Augen durchmessen hat, dem werden die zahlreichen, zum Teil monumentalen Grablegen vergangener Päpste in Erinnerung geblieben sein. -

Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome,” 1955

“Decorazioni barocche in San Silvestro in Capite a Roma,” Bollettino d’arte, XLII, 1957, 44-9 Original English version “The Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome,” 1955 (click here for first page) The Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome Irving Lavin Harvard University February, 1955 The Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome In the last quarter of the seventeenth century the Franciscan sisters of the order of Santa Clara began a thorough renovation of the church of which they had been proprietors since the thirteenth century, San Silvestro in Capite.1 The great wealth of the order made it possible to employ the ablest artists of the day, and by the time the task was completed in the early eighteenth century the church could boast of some of the major monuments of late Baroque art in Rome (Fig. 1). The great ceiling paintings of Giacinto Brandi and Ludovico Gimignani, the altarpieces of Giuseppe Chiari, the sculptures of Lorenzo Ottoni and Camillo Rusconi, and the facade by Domenico de′ Rossi, contribute to make the church’s decorations indispensable for an understanding of the stylistic development of the period. Knowledge of this contribution, however, has been severely limited by an almost exclusive dependence on the sparse notices given in early biographers and guide books, such as Pascoli and Titi. It is extremely fortunate therefore in that the archives of the convent which contain the documents relating to the decorations are still preserved in the Archivio di Stato of Rome. The most important of these documents are gathered together and transcribed in the Appendix to this notice.2 They permit a nearly complete reconstruction of the history of the decorations (Fig. -

Angeli Su Roma Quanti Angeli Volano Su Roma? E Dove? Andiamo a Scoprirli

ANGELI SU ROMA QUANTI ANGELI VOLANO SU ROMA? E DOVE? ANDIAMO A SCOPRIRLI INTRODUZIONE In molte religioni, non solo in quella cristiana cattolica, esistono gli angeli, sono esseri spirituali che assistono e servono Dio oppure sono al servizio dell'uomo nella sua vita terrena e nel suo percorso di progresso spirituale. Il termine latino angelus deriva dal greco anghelos (già attestato nel dialetto miceneo del XIV/XII sec) significa inviato, messaggero e nelle credenze religiose della civiltà classica appare come messaggero degli Dei. Hermes o Mercurio è indicato come anghelos. Con la stessa funzione lo indica Platone nel Cratilo, i filosofi pitagorici consideravano che i sogni erano inviati agli uomini dagli angeli, anche Platone - nel Convivio - parla di daimon, ministri di Dio che sono vicini agli uomini per ben ispirarli. Ma la figura dell'angelo nella visione cristiana deriva certamente dal pensiero religioso ebraico dove il termine angelo è usato nei testi biblici sempre con il significato di "inviato" di "messaggero". Il Cristianesimo ha ereditato la nozione di angeli dalla cultura religiosa biblico ebraica, soprattutto di lingua greca, ma le figure degli angeli sono ridisegnate secondo il Nuovo Testamento. Così l'angelo ebraico nominato nel libro di Daniele Gabiel, è nei Vangeli il Gabriele angelo dell'Annunciazione. Anche nel Cattolicesimo gli angeli sono creature di Dio spirituali, incorporee ma personali, cioè dotate di intelligenza e volontà propria, tra gli esseri visibili sono quelli con il più alto grado di perfezione. La loro esistenza è una verità di fede. Gli angeli hanno anche la funzione di assistere e proteggere la Chiesa e la vita umana. -

Dinner in Piazza Della Rotonda

Pont. Max. Campo Marzio feet in width and fifteen feet in depth The entire interior space of the Pantheon mea- sures some 142 feet in diameter, as well as in height—a perfect sphere—large enough to contain the aforementioned dome of St Peter’s or the nave of Chartres Cathedral; yet unlike Chartres, a completely freestanding structure As I proceeded to the center of this immense rotunda, I found myself completing a 360 degree circuit beneath the oculus to take it all in—an idealized circle of Had- rian’s invulnerable empire and representation of heaven itself; the physical sanction of “all the gods” that Rome (under Hadrian, of course) should rule the world But the Pantheon’s interior is more than a doorway to Rome’s imperial past, for the tombs in its pavement and niches are also windows into the Italian Renaissance and the Risorgi- mento under the Savoy kings Along the western wall above the pavement I visited the tomb of Raphael, who had requested in his will to be buried in the Church of Santa Maria della Rotonda, as the Pantheon has also been known ever since Pope Boniface IV (608–615) received it from the Byzantine Emperor Phocas and converted it into a church in dedication to the Virgin and all the Christian martyrs Further on, toward the altar that rests against the wall opposite the entrance, I came upon the tomb of the Savoy King Umberto I, and continuing past the altar to the right, were the highly ornamented tombs of the Savoys Vittorio Emanuele II and Umberto II The inscription for Victor Emmanuel II reads: “Vittorio Emanuele -

Trastevere (Map P. 702, A3–B4) Is the Area Across the Tiber

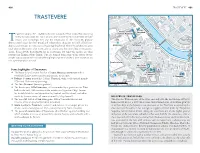

400 TRASTEVERE 401 TRASTEVERE rastevere (map p. 702, A3–B4) is the area across the Tiber (trans Tiberim), lying below the Janiculum hill. Since ancient times there have been numerous artisans’ Thouses and workshops here and the inhabitants of this essentially popular district were known for their proud and independent character. It is still a distinctive district and remains in some ways a local neighbourhood, where the inhabitants greet each other in the streets, chat in the cafés or simply pass the time of day in the grocery shops. It has always been known for its restaurants but today the menus are often provided in English before Italian. Cars are banned from some of the streets by the simple (but unobtrusive) method of laying large travertine blocks at their entrances, so it is a pleasant place to stroll. Some highlights of Trastevere ª The beautiful and ancient basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere with a wonderful 12th-century interior and mosaics in the apse; ª Palazzo Corsini, part of the Gallerie Nazionali, with a collection of mainly 17th- and 18th-century paintings; ª The Orto Botanico (botanic gardens); ª The Renaissance Villa Farnesina, still surrounded by a garden on the Tiber, built in the early 16th century as the residence of Agostino Chigi, famous for its delightful frescoed decoration by Raphael and his school, and other works by Sienese artists, all commissioned by Chigi himself; HISTORY OF TRASTEVERE ª The peaceful church of San Crisogono, with a venerable interior and This was the ‘Etruscan side’ of the river, and only after the destruction of Veii by remains of the original early church beneath it; Rome in 396 bc (see p. -

Delibera Assemblea Capitolina N 43/2019

Protocollo RC n. 22420/18 Deliberazione n. 43 ESTRATTO DAL VERBALE DELLE DELIBERAZIONI DELL’ASSEMBLEA CAPITOLINA Anno 2019 VERBALE N. 35 Seduta Pubblica del 6 giugno 2019 Presidenza: STEFÀNO L’anno 2019, il giorno di giovedì 6 del mese di giugno alle ore 14,07 nel Palazzo Senatorio, in Campidoglio, si è adunata l’Assemblea Capitolina in seduta pubblica, previa trasmissione degli avvisi per le ore 14 dello stesso giorno, per l’esame degli argomenti iscritti all’ordine dei lavori e indicatinei medesimi avvisi. Partecipa alla seduta il sottoscritto Vice Segretario Generale Vicario, dott.ssa Mariarosa TURCHI. Assume la presidenza dell’Assemblea Capitolina il Vice Presidente Vicario Enrico STEFÀNO il quale dichiara aperta la seduta e dispone che si proceda, ai sensi dell'art. 35 del Regolamento, all’appello dei Consiglieri. (OMISSIS) Alla ripresa dei lavori - sono le ore 14,47 - il Vice Presidente Vicario dispone che si proceda al secondo appello. Eseguito l’appello, il Vice Presidente Vicario comunica che sono presenti i sottoriportati n. 25 Consiglieri: Agnello Alessandra, Angelucci Nello, Ardu Francesco, Bernabei Annalisa, Calabrese Pietro, Catini Maria Agnese, Chiossi Carlo Maria, Coia Andrea, Corsetti Orlando, Di Palma Roberto, Diaco Daniele, Donati Simona, Guadagno Eleonora, Guerrini Gemma, Iorio Donatella, Montella Monica, Pacetti Giuliano, Paciocco Cristiana, Penna Carola, Seccia Sara, Stefàno Enrico, Sturni Angelo, Terranova Marco, Tranchina Fabio e Vivarelli Valentina. 2 ASSENTI l'on.le Sindaca Virginia Raggi e i seguenti Consiglieri: Baglio Valeria, Bordoni Davide, Celli Svetlana, De Priamo Andrea, Diario Angelo, Fassina Stefano, Ferrara Paolo, Ficcardi Simona, Figliomeni Francesco, Giachetti Roberto, Grancio Cristina, Marchini Alfio, Meloni Giorgia, Mennuni Lavinia, Mussolini Rachele, Onorato Alessandro, Palumbo Marco, Pelonzi Antongiulio, Piccolo Ilaria, Politi Maurizio, Tempesta Giulia, Zannola Giovanni e Zotta Teresa Maria.