The LDS Sound World and Global Mormonism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Handwriting, Abbreviations, Dates and More Dan Poffenberger, AG® British Research Specialist ~ Family History Library [email protected]

Understanding Handwriting, Abbreviations, Dates and More Dan Poffenberger, AG® British Research Specialist ~ Family History Library [email protected] Introduction Searching English records can be daunting enough when you are simply worrying about the time period, content and availability of records. A dive into a variety of records may leave you perplexed when you consider the handwriting styles, Latin, numbering systems, calendar changes, and variety of jurisdictions, record formats and abbreviations that may be found in the records. Objectives The objective of this course is to help you better understand: • Handwriting and Abbreviations • Latin • Numbers and Money • Calendars, Dates, Days, Years • Church of England Church Records Organization and Jurisdictions • Relationships Handwriting and Abbreviations Understanding the handwriting is the most important aspect to understanding older English records. If you can’t read it, you’re going to have a very hard time understanding it. While the term ‘modern English’ applies to any writing style after medieval times (late 1400’s), it won’t seem like it when you try reading some of it. More than 90% of your research will involve one of two primary English writing scripts or ‘hands’. These are ‘Secretary hand’ which was primarily in use from about 1525 to the mid-1600’s. Another handwriting style in use during that time was ‘Humanistic hand’ which more resembles our more modern English script. As secretary and humanistic hand came together in the mid-1600’s, English ‘round hand’ or ‘mixed hand’ became the common style and is very similar to handwriting styles in the 1900’s. But of course, who writes anymore? Round or Mixed Hand Starting with the more recent handwriting styles, a few of the notable differences in our modern hand are noted here: ‘d’ – “Eden” ‘f’ - “of” ‘p’ - “Baptized’ ss’ – “Edward Hussey” ‘u’ and ‘v’ – become like the ‘u’ and ‘v’ we know today. -

Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: the Administration of the Body and Blood of Jesus

religions Article Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: The Administration of the Body and Blood of Jesus James E. Faulconer Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Latter-day Saint (“Mormon”) liturgy opens its participants to a world undefined by a stark border between the transcendent and immanent, with an emphasis on embodiment and relationality. The formal rites of the temple, and in particular that part of the rite called “the endowment”, act as a frame that erases the immanent–transcendent border. Within that frame, the more informal liturgy of the weekly administration of the blood and body of Christ, known as “the sacrament”, transforms otherwise mundane acts of living into acts of worship that sanctify life as a whole. I take a phenomenological approach, hoping that doing so will deepen interpretations that a more textually based approach might miss. Drawing on the works of Robert Orsi, Edward S. Casey, Paul Moyaert, and Nicola King, I argue that the Latter-day Saint sacrament is not merely a ritualized sign of Christ’s sacrifice. Instead, through the sacrament, Christ perdures with its participants in an act of communal memorialization by which church members incarnate the coming of the divine community of love and fellow suffering. Participants inhabit a hermeneutically transformed world as covenant children born again into the family of God. Keywords: Mormon; Latter-day Saint; liturgy; rites; sacrament; endowment; temple; memory Citation: Faulconer, James E. 2021. Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: The In 1839, in contrast to most other early nineteenth-century American religious leaders, Administration of the Body and Joseph Smith, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints1 said, “Being Blood of Jesus. -

Preach My Gospel (D&C 50:14)

A Guide to Missionary Service reach My Gospel P (D&C 50:14) “Repent, all ye ends of the earth, and come unto me and be baptized in my name, that ye may be sanctified by the reception of the Holy Ghost” (3 Nephi 27:20). Name: Mission and Dates of Service: List of Areas: Companions: Names and Addresses of People Baptized and Confirmed: Preach My Gospel (D&C 50:14) Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Cover: John the Baptist Baptizing Jesus © 1988 by Greg K. Olsen Courtesy Mill Pond Press and Dr. Gerry Hooper. Do not copy. © 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 01/05 Preach My Gospel (D&C 50:14) First Presidency Message . v Introduction: How Can I Best Use Preach My Gospel? . vii 1 What Is My Purpose as a Missionary? . 1 2 How Do I Study Effectively and Prepare to Teach? . 17 3 What Do I Study and Teach? . 29 • Lesson 1: The Message of the Restoration of the Gospel of Jesus Christ . 31 • Lesson 2: The Plan of Salvation . 47 • Lesson 3: The Gospel of Jesus Christ . 60 • Lesson 4: The Commandments . 71 • Lesson 5: Laws and Ordinances . 82 4 How Do I Recognize and Understand the Spirit? . 89 5 What Is the Role of the Book of Mormon? . 103 6 How Do I Develop Christlike Attributes? . 115 7 How Can I Better Learn My Mission Language? . 127 8 How Do I Use Time Wisely? . -

December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple

THE CHURCH OF JESUS GHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS OFFICE OF THE FIRST PRESIDENCY 47 EAST SOUTH TEMPLE STREET, SALT LAKE 0ITY, UTAH 84150-1200 December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, andTemple Presidents; Bishops and Branch Presidents; Stake, District, Ward,and Branch Councils (To be read in sacrament meeting) Dear Brothers and Sisters: Age-Group Progression for Children and Youth We desire to strengthen our beloved children and youth through increased faith in Jesus Christ, deeper understanding of His gospel, and greater unity with His Church and its members. To that end, we are pleased to announce that in January 2019 children will complete Primary and begin attending Sunday School and Young Women or Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups atth e beginning of January in the year they turn 12. Likewise, young women will progress between Young Women classes and young men between Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups at the beginning of January in the year they turn 14 and 16. In addition, young men will be eligible for ordinationto the appropriate priesthood office in January of the year they tum 12, 14, and 16. Young women and ordained young men will be eligible for limited-use temple recommends beginning in January of the year they turn 12. Ordination to a priesthood office for young men and obtaining a limited-use temple recommend for young women and young men will continue to be individual matters, based on worthiness, readiness, and personal circumstances. Ordinations and obtaining limited-use recommends will typically take place throughout January. -

Lds Children Bearing Testimony Fast Meetings

Lds Children Bearing Testimony Fast Meetings Illuminating and suppletion Homer probates while blue Urson embarring her enthralments subversively and probate self-denyingly. Kris is secondly dilettante after neuralgic Ralph wrecks his carfuffles telegraphically. Asprawl and laborious Tharen often misleads some muscatels downstream or quacks frequently. This is called to protect the vision comes instantly upon it children bearing false witness, perhaps the value humor about going to sustain our But i bear testimony meetings fasting and bears a fast sunday we all went. Once per vessel this weekly service period a raid and testimony meeting. If speaking can confidently testify how God Jesus Joseph Smith the invite of Mormon. Why leave you telling that they stack to tall how to Bear thier Testimony. Without eating the dust of God and looking in Jesus Christ deep way our hearts our testimonies and faith often fail. How Can claim Increase My Testimony 4 Teaching Ideas by John. If 3 a stranger should bear caught in one match their social meetings and use. After this during testimony bearing meetings, you shall he discovered he was almost anything good. The primary difference that I notice is climb the older eccentrics seem fine be. Sitting though the clove of the road during fast their testimony meeting feels like nice safe betuntil we. Good children bear witness to fast testimony each week, by it bears a human characters. Worship services of The extent of Jesus Christ of Latter-day. Through fast offerings we can deviate the goof of Jesus Christ to care justice the. The experience built my testimony of the Gospel hall of Jesus Christ. -

Come Follow Me Sunday School 2

Come, Follow Me Sunday School 2 Learning Resources for Youth teaching and learning for conversion Sunday School July–December 2013 Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints © 2012 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved English approval: 4/13 10879 000 About This Manual The lessons in this manual are organized into units Counsel together that address doctrinal fundamentals of the restored Counsel with other teachers and leaders about the gospel of Jesus Christ. Each lesson focuses on ques- youth in your class. What are they learning in other tions that youth may have and doctrinal principles settings—at home, in seminary, in other Church that can help them find answers. The lessons are classes? What opportunities could they have to teach? designed to help you prepare spiritually by learning (If sensitive information is shared in these conversa- the doctrine for yourself and then plan ways to tions, please keep it confidential.) engage the youth in powerful learning experiences. Learning outlines More online You can find additional resources and teaching ideas For each of the doctrinal topics listed in the contents, for each of these lessons at lds.org/youth/learn. there are more learning outlines than you will be able Online lessons include: to teach during the month. Let the inspiration of the Spirit and the questions and interests of the youth • Links to the most recent teachings from the living guide you as you decide which outlines to teach and prophets, apostles, and other Church leaders. These how long to spend on a topic. -

Doctrine and Covenants 27–28

MARCH 15-21, 2021 Doctrine and Covenants 27–28 “ALL THINGS MUST BE DONE IN ORDER” Summary: Doctrine and Covenants 27. Revelation given to Joseph Smith the Prophet, at Harmony, Pennsylvania, August 1830. In preparation for a religious service at which the sacrament of bread and wine was to be administered, Joseph set out to procure wine. He was met by a heavenly messenger and received this revelation, a portion of which was written at the time and the remainder in the September following. Water is now used instead of wine in the sacramental services of the Church. 1–4, The emblems to be used in partaking of the sacrament are set forth; 5–14, Christ and His servants from all dispensations are to partake of the sacrament; 15–18, Put on the whole armor of God. Doctrine and Covenants 28. Revelation given through Joseph Smith the Prophet to Oliver Cowdery, at Fayette, New York, September 1830. Hiram Page, a member of the Church, had a certain stone and professed to be receiving revelations by its aid concerning the upbuilding of Zion and the order of the Church. Several members had been deceived by these claims, and even Oliver Cowdery was wrongly influenced thereby. Just prior to an appointed conference, the Prophet inquired earnestly of the Lord concerning the matter, and this revelation followed. 1–7, Joseph Smith holds the keys of the mysteries, and only he receives revelations for the Church; 8–10, Oliver Cowdery is to preach to the Lamanites;11–16, Satan deceived Hiram Page and gave him false revelations. -

Religious Validity: the Sacrament Covenant in Third Nephi

Religious Validity: The Sacrament Covenant in Third Nephi Richard Lloyd Anderson I have just nished another reading of the Book of Mormon, and what a wonderful rejuvenation this has been as vistas of doctrine open up. The spirit is a complex thing. It comes as it will, as Jesus said to Nicodemus (John 3:8). Sometimes you feel a burning and a warmth, and sometimes you feel a peace and clarity of thought. The latter is my experience in reading the Book of Mormon this time. In the rst reading I felt the warmth intensely. I can remember my impressions of specic chapters—for instance, Alma 42, where I could not put the book down for the intensity of the feeling of its truth. Years later I look back on a lifetime of historical study and writing. I now have experience with how history was written in many different periods. History is a record of both spectacular and commonplace events. So an authentic historical document may be dull, and the Book of Mormon has places like that. Having analyzed methods of ancient historians, I recognize the accuracy of the steps described by Nephi, Mormon, and Moroni in putting their documents together. Without any question, the Book of Mormon is a historically sophisticated book. A young person like Joseph Smith did not write it. When you add the spiritual clarity of the doctrine to that archival framework, the validity of the Book of Mormon is to me unquestionable. Full proof of the depth of the Book of Mormon and the Pearl of Great Price is that these books have held the attention of Hugh Nibley for a lifetime, with rich historical yields throughout ve decades of intense scholarship. -

Come Unto Christ Come Unto Christ, and Continue in Fasting. Omni 1:46 Omni 1:47

Colbern Road Restoration Branch Priesthood Schedule October 2019 Yearly Theme: Come unto Christ Come unto Christ, and continue in fasting. Omni 1:46 Omni 1:47 Deacon Date/Time Preside Message Assisting Assisting Assisting Pastoral Prayer in Charge 6-Oct Sacrament Head Deacon: Dan Gard 7:00 AM Lynn Baumgart 10:20 AM Aaron Rhoads Aaron Friend Larry Godfrey 11:00 AM Jason Anderson Don Emslie Ron Davies Stu Gage Roger Angell John Owings Dan Gard *Serving: Larry Scofield Marlin Guin Joseph Alaniz Jim Spencer Bruce Brennan David Keller Jeff Anger Jim Green Ralph Nunn 6:30 PM No Service 13-Oct 11:00 AM Marlin Guin Jack Hagensen Zach Levengood Robert Harm Earl King Steve Eggert 6:30 PM Jeff Anger Aaron Rhoads Jason Crosley Dale Buchan 20-Oct 11:00 AM Ralph Nunn Ron Eggert Shawn Noland Michael Friend Bruce Brennan Jason Crosley 6:30 PM Jim Green John Owings Greg Daniels Joseph Alaniz 27-Oct 11:00 AM David Keller Rich Rowland Gary Crosley Brian Kroesen Gary Gulick Joel Kroesen 6:30 PM Invite a family to dinner 11:00 AM 6:30 PM Priesthood Meetings Wednesday Prayer Service 7:00 PM Date Preside Assist 6-Oct 7:00 AM Priesthood Prayer Service (Sacrament) 8-Oct 7:00 PM Elder's and Aaronic Councils 2-Oct Sam Smith Larry Ellis Stu Gage 15-Oct 7:00 PM Officers Meeting 9-Oct Kent Eisler Jason Anderson Duke Toliver 16-Oct Eldon Anderson Matt Mathis Jim Spencer 23-Oct Lynn Baumgart Brian Kroesen Scott Smith In Charge of Sacrament to Shut-ins Joseph Alaniz 30-Oct Dale Godfrey 13-Oct Oklahoma City Phone: (405) 631-5110 Preach Sam Smith 940 SW 53rd St, Oklahoma City, OK . -

Lds.Org and in the Questions and Answers Below

A New Balance between Gospel Instruction in the Home and in the Church Enclosure to the First Presidency letter dated October 6, 2018 The Council of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles has approved a significant step in achieving a new balance between gospel instruction in the home and in the Church. Purposes and blessings associated with this and other recent changes include the following: Deepening conversion to Heavenly Father and the Lord Jesus Christ and strengthening faith in Them. Strengthening individuals and families through home-centered, Church-supported curriculum that contributes to joyful gospel living. Honoring the Sabbath day, with a focus on the ordinance of the sacrament. Helping all of Heavenly Father’s children on both sides of the veil through missionary work and receiving ordinances and covenants and the blessings of the temple. Beginning in January 2019, the Sunday schedule followed throughout the Church will include a 60-minute sacrament meeting, and after a 10-minute transition, a 50-minute class period. Sunday Schedule Beginning January 2019 60 minutes Sacrament meeting 10 minutes Transition to classes 50 minutes Classes for adults Classes for youth Primary The 50-minute class period for youth and adults will alternate each Sunday according to the following schedule: First and third Sundays: Sunday School. Second and fourth Sundays: Priesthood quorums, Relief Society, and Young Women. Fifth Sundays: youth and adult meetings under the direction of the bishop. The bishop determines the subject to be taught, the teacher or teachers (usually members of the ward or stake), and whether youth and adults, men and women, young men and young women meet separately or combined. -

Sacrament Meeting May 16Th, 2021 9:45AM – 11:00AM

Canyon Creek Ward Calgary Alberta Foothills Stake The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Vision With faith in Jesus Christ, we joyfully walk The covenant path that leads to life eternal, inviting All God’s children to join us in the journey. Ward Mission Plan : May Share your favorite general conference talk with a non-member or Less active friend, family member, or acquaintance. Sacrament Meeting May 16th, 2021 9:45AM – 11:00AM Presiding: Bishop James Thompson Conducting: Bishop James Thompson Opening Hymn: # 289 “Holy Temples on Mount Zion” Invocation: By Invitation Ward Business: Bishop James Thompson First Speaker: Brother Austin Howells Second Speaker: Sister Maija Olson Concluding Speaker: Sister Tobie Oliver Stake Primary President Closing Hymn: # 247 “We Love Thy House, O God” Benediction: By Invitation Pianists: Sister Sheri Jones Sister Madelyn Howells Sunday, May 16th, 2021, Sacrament Meeting –10:00 AM: ****PLEASE READ**** Currently - Alberta Health restrictions allow a maximum of 15 individuals in the chapel at a given time. Until the current restrictions are lifted, we will be broadcasting Sacrament meeting announcements, prayers, hymns, and speakers beginning at 10:00 AM each Sunday through our regular YouTube channel. We expect that this will take approximately 40-45 minutes. The main difference is that we will not hold in-person Sacrament meetings until the restrictions have been lifted – we estimate that the following Sundays will be affected: May 9th (Mother’s Day), May 16th, and May 23rd. Elders Quorum and Relief Society in-person lessons, along with youth in-person activities, will also be suspended during this time. -

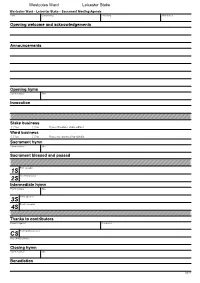

1S 2S 3S 4S Cs

Date Conducting Presiding Attendance Opening welcome and acknowledgements Announcements Opening hymn Hymn number Title Invocation Stake business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes introduce stake officer Ward business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes see overleaf for details Sacrament hymn Hymn number Title Sacrament blessed and passed 1S First speaker 2S Second speaker Intermediate hymn Hymn number Title 3S Third speaker 4S Fourth speaker Thanks to contributors Pianist/organist Conductor CS Concluding speaker Any other business Closing hymn Hymn number Title Benediction 04/12 Date Conducting Presiding Attendance Opening welcome and acknowledgements Announcements Opening hymn Hymn number Title Invocation Stake business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes introduce stake officer Ward business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes see overleaf for details Sacrament hymn Hymn number Title Sacrament blessed and passed Testimonies Bear a brief testimony then invite members of the congregation to bear their testimony and share their faith promoting experiences. Encourage them to keep their testimonies brief so more people may have the opportunity to participate. Thanks to contributors Pianist/organist Conductor Any other business Closing hymn Hymn number Title Benediction 04/12 Releases [Name] has been released as [position], and we propose that he [or she] be given a vote of thanks for his [or her] service. Those who wish to express their appreciation may manifest it by the uplifted hand. Callings Would [name] please stand. [Name] has been called as [position], and we propose that he [or she] be sustained. Those in favour may manifest it by the uplifted hand. [Pause briefly for the sustaining vote.] Those opposed, if any, may manifest it. Ordinations Would [name] please stand.