Whitechapel Bell Foundry (Bells of Middlesex, Part III) by W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Finest and Most Complete Virtual Bell Instrument Available

Platinum Advanced eXperience by Chime Master The finest and most complete virtual bell instrument available. Front and center on the Platinum AX™ is a color touch screen presenting intuitive customizable menus. Initial setup screens clearly guide you with questions about your traditions, ringing preferences and schedule needs. The Platinum AX ™ features our completely remastered high definition Chime Master HD-Bells™. Choose your bell voice from twenty-five meticulously sampled authentic bell instruments including several chimes and carillons cast by European and historic American foundries. Powerful front facing speakers provide inside ringing and practice sound when you play or record the bells using a connected keyboard. Combined with a Chime Master inSpire outdoor audio system with full-range speakers, the reproduction of authentic cast bronze bells is often mistaken for a tower of real bells. An expansive library of selections includes thousands of hymns in various arrangements and multiple customizable ringing functions. You may expand your collection by personally recording or importing thousands more. Control your bells remotely from anywhere with Chime Master’s exclusive Chime Center™. This portal seam- lessly integrates online management and remote control. Online tools facilitate schedule changes, backup of recordings and settings, as well as automatic updates as soon as they are available! ® Where tradition meets innovation. ™ Virtual Bell Instrument FEATURES HD-Bells™ Built-In Powerful Monitor Speakers Twenty-five of the highest quality bell Exceptional monitoring of recording and instruments give your church a distinctive voice performances built right into the cabinet. in your community. Built-In Network Interface Enhanced SmartAlmanac™ Easy remote control via your existing smart Follows the almanac calendar and plays music phone or device. -

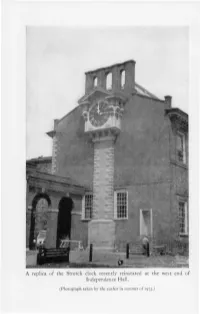

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

SAVED by the BELL ! the RESURRECTION of the WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a Proposal by Factum Foundation & the United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust

SAVED BY THE BELL ! THE RESURRECTION OF THE WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a proposal by Factum Foundation & The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust Prepared by Skene Catling de la Peña June 2018 Robeson House, 10a Newton Road, London W2 5LS Plaques on the wall above the old blacksmith’s shop, honouring the lives of foundry workers over the centuries. Their bells still ring out through London. A final board now reads, “Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 1570-2017”. Memorial plaques in the Bell Foundry workshop honouring former workers. Cover: Whitechapel Bell Foundry Courtyard, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. Back Cover: Chains in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. CONTENTS Overview – Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 1 A Brief History of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel 9 2 The Whitechapel Bell Foundry – Summary of the Situation 11 3 The Partners: UKHBPT and Factum Foundation 12 3 . 1 The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust (UKHBPT) 12 3 . 2 Factum Foundation 13 4 A 21st Century Bell Foundry 15 4 .1 Scanning and Input Methods 19 4 . 2 Output Methods 19 4 . 3 Statements by Participating Foundrymen 21 4 . 3 . 1 Nigel Taylor of WBF – The Future of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 21 4 . 3 . 2 . Andrew Lacey – Centre for the Study of Historical Casting Techniques 23 4 . 4 Digital Restoration 25 4 . 5 Archive for Campanology 25 4 . 6 Projects for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 27 5 Architectural Approach 28 5 .1 Architectural Approach to the Resurrection of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel – Introduction 28 5 . 2 Architects – Practice Profiles: 29 Skene Catling de la Peña 29 Purcell Architects 30 5 . -

Size-Frequency Relation and Tonal System in a Set of Ancient Chinese Bells: Piao-Shi Bianzhong

J. Acoust.Soc. Jpn. (E)10, 5 (1989) Size-frequency relation and tonal system in a set of ancient Chinese bells: Piao-shi bianzhong Junji Takahashi MusicResearch Institute, Osaka College of Music, Meishin-guchi1-4-1, Toyonaka, Osaka, 561 Japan (Received5 April 1989) Resonancefrequencies and tonalsystem are investigatedon a setof ancientChinese bells named"Piao-shi bianzhong." According to the measurementof 12 bellspreserved in Kyoto,it is foundthat a simplerelation between frequency and sizeholds well. The relationtells frequency of a bellinversely proportional to squareof its linearmeasure. It is reasonableto concludethat the set wascast for a heptatonicscale which is very similarto F# majorin our days. Precedingstudies in historyand archaeologyon Piao- shi bellsare also shortlyreviewed. PACSnumber: 43. 75.Kk •Ò•à) in Kyoto. In ƒÌ ƒÌ 2 and 3, historical and 1. INTRODUCTION archaeological studies on the set will be reviewed. In China from 1100 B.C. or older times (Zhou In ƒÌ 6, musical intervals of the set will be examined and it will be discussed for what tonal system the period), bronze bells named "zhong" (•à) of special shape with almond-like cross section and downward bells were cast. mouth had been cast and played in ritual orchestra. 2. SHORT REVIEW ON After the excavation of a set of 64 zhong bells in 1978 PIAO—SHI BIANZHONG from the tomb or Marquis Yi of Zeng (˜ðŒò‰³), vigorous investigations have been concentrated upon In about 1928, many bronze wares including some zhong bells from many fields of researches as ar- zhong bells were excavated from tombs of Jincun chaeology, history, musicology, and, acoustics. -

About CHANGE RINGING

All about CHANGE RINGING Provide a pop-up display explaining change-ringing to those attending and visiting the church. Page 6 METHODS RINGING METHODSThe mechanics of a bell It is traditional to start and Theswinging mechanics full-circle of a bell swinging means finish ringing with rounds full-circlethat we meansneed tothat restrict we need its to restrictmove its moveto one to oneposition. position. Not possible: Possible: Possible: Possible: The traditional notation shows each bell as a number starting at ‘1’ for the treble 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (lightest bell) and running down the numbers to the tenor (heaviest bell). | X | | | | | | X X X | X X X X Bells are usually tuned to the major scale. If there are more than 9 bells, letters 4 8 2Provide 6 7 a1 pop-up 3 5 display 1 3explaining 2 4 5 change-ringi 6 7 8 ng to1 those3 2 attending 5 4 7 and6 8visiting 2the 1 church. 4 3 Page6 5 78 7 The basic method incorporating this rule is called … are substituted, so 0 = 10, E =11, T = 12, A = 13, B = 14, C = 15, D = 16. The1 2 basic3 4 5 6 method 7 8 incorporating this rule is called … X X X X Strokes 2 1Provide 4 3 a6 pop-up 5 8 display7 Now,explaining if change-ringiwe drawng ato linethose attendingjoining and up visiting the the church. -

Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. Deborah’s voice can be found across every page. I am indebted to the musicians without whom my dissertation would not be possible. Priya Gopal, Vijay Iyer, Amir ElSaffar, and Hafez Modirzadeh gave so much of their time and energy to this project. -

Campaign Fact Book Former Whitechapel Bell Foundry Site Whitechapel, London

Campaign Fact Book Former Whitechapel Bell Foundry Site Whitechapel, London Compiled January 2020 Whitechapel Bell Foundry: a matter of national importance This fact book has been compiled to capture the breadth of the campaign to save the site of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which is currently threatened by a proposal for conversion into a boutique hotel. Re-Form Heritage; Factum Foundation; numerous community, heritage and bellringing organisations; and thousands of individuals have contributed to and driven this campaign, which is working to: reinstate modern and sustainable foundry activity on the site preserve and record heritage skills integrate new technologies with traditional foundry techniques maintain and build pride in Whitechapel’s bell founding heritage The site of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry is Britain’s oldest single-purpose industrial building where for generations bells such as Big Ben, the Liberty Bell, Bow Bells and many of the world’s great bells were made. Bells made in Whitechapel have become the voices of nations, marking the world’s celebrations and sorrows and representing principles of emancipation, freedom of expression and justice. As such these buildings and the uses that have for centuries gone on within them represent some of the most important intangible cultural heritage and are therefore of international significance. Once the use of the site as a foundry has gone it has gone forever. The potential impact of this loss has led to considerable concern and opposition being expressed on an unprecedented scale within the local area, nationally and, indeed, internationally. People from across the local community, London and the world have voiced their strong opposition to the developer’s plans and to the hotel use and wish for the foundry use to be retained. -

A Proposed Campanile for Kansas State College

A PROPOSED CAMPANILE FOR KANSAS STATE COLLEGE by NILES FRANKLIN 1.1ESCH B. S., Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, 1932 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE KANSAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND APPLIED SCIENCE 1932 LV e.(2 1932 Rif7 ii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 THE EARLY HISTORY OF BELLS 3 BELL FOUNDING 4 BELL TUNING 7 THE EARLY HISTORY OF CAMPANILES 16 METHODS OF PLAYING THE CARILLON 19 THE PROPOSED CAMPANILE 25 The Site 25 Designing the Campanile 27 The Proposed Campanile as Submitted By the Author 37 A Model of the Proposed Campanile 44 SUMMARY '47 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 54 LITERATURE CITED 54 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this thesis is to review and formulate the history and information concerning bells and campaniles which will aid in the designing of a campanile suitable for Kansas State College. It is hoped that the showing of a design for such a structure with the accompanying model will further stimulate the interest of both students, faculty members, and others in the ultimate completion of such a project. The design for such a tower began about two years ago when the senior Architectural Design Class, of which I was a member, was given a problem of designing a campanile for the campus. The problem was of great interest to me and became more so when I learned that the problem had been given to the class with the thought in mind that some day a campanile would be built. -

![Dove, Ronald H.] World 2018 CCCBR](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8339/dove-ronald-h-world-2018-cccbr-668339.webp)

Dove, Ronald H.] World 2018 CCCBR

ST MARTIN'S GUILD OF CHURCH BELL RINGERS: LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE CATALOGUE 9: BELLS, BELL-FOUNDERS AND BELL ARCHAEOLOGY - GENERAL Accession Category Author Title Date Publisher and other details Number Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers to the Ringing Bells of Britain and of the NA724 BBG [Dove, Ronald H.] World 2018 CCCBR. 11th edition [Dove, Ronald H.], Baldwin, Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers to the Ringing Bells of Britain and of the NA641 BBG John, Johnston, Ronald World 2012 CCCBR. 10th edition Acland-Troyte, J. E. and R. H. A025 BBG D. The Change Ringers' Guide to the Steeples of England 1882 London A4 presentation edition. Presented by the St Paul's Bells' NA623 BBG Anonymous St Paul's Church Birmingham: a peal of ten bells. Donors' Book 2010 Committee With CD recording of previous steel bells. Presented by the NA656 BBG Anonymous A New Voice for St Mary's Church Moseley. Donors' Book 2014 Moseley ringers NA427 BBG Baldwin, John Four Bell Towrs: a supplement to Dove's Guide 1989 Cardiff. Bound NA364 BBG Camp, J. Discovering Bells and Bellringing 1968 Tring NA683 BBG Camp, J. Discovering Bells and Bellringing 1975 Wingrave. 2nd edition Aldershot. 1st edition. Rebound in plain hard covers. NA445 BBG Dove, Ronald H. A Bellringers' Guide to the Church Bells of Britain 1950 Presented by George Chaplin NA5180 BBG Dove, Ronald H. A Bellringers' Guide to the Church Bells of Britain 1950 Aldershot. 1st edition. Original covers NA5190 BBG Dove, Ronald H. A Bellringers' Guide to the Church Bells of Britain 1956 Aldershot. -

The Bells Were the St

1989. At the same time some of the bells were The St. Mary’s and St John’s Ringers The Bells reconfigured and the clock mechanism changed to go The Ringers are a joint band for both White Waltham around the wall rather than across the ringing chamber. and Shottesbrooke, a voluntary group under the & leadership of our Tower Captains, and we belong to the Bell Weight Note Date Founder Sonning Deanery Branch of the Oxford Diocesan Guild Bell Ringing Cwt- of Church Bell Ringers, founded in 1881. 1 4-0-0 E 1989 Recast by Whitechapel at The joint band (St Mary’s and St John’s) of bell-ringers 2 4-3-24 D 1989 Recast by Whitechapel is a very friendly group that welcomes new members. St. Mary’s and St John’s As well as our regular weekly practice sessions and 3 5-3-3 C 1989 Recast by Whitechapel ringing for Sunday service, we sometimes arrange an Churches outing to ring at other towers. 4 6-3-1 B 1989 Recast by Whitechapel 5 8-3-25 A 1989 Recast by Whitechapel We ring bells for: Sunday services and Weddings 6 12-0-9 G 1989 Recast by Whitechapel Special celebrations such as Christmas Day and St. John’s and its bells New Year’s Eve The church is set in the grounds of the Shottesbrooke Estate. The six bells are in good working order and are of some Civic occasions such as Remembrance Day antiquity. Three of the bells date from the first half of the 17th century, with the newest (the treble) being added in Practice evening is Friday 7.30 – 9p.m. -

A New History of the Carillon

A New History of the Carillon TIFFANY K. NG Rombouts, Luc. Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music. Translated by Com- municationwise. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014, 368 pp. HE CARILLON IS HIDDEN IN plain sight: the instrument and its players cannot be found performing in concert halls, yet while carillonneurs and Tkeyboards are invisible, their towers provide a musical soundscape and focal point for over six hundred cities, neighborhoods, campuses, and parks in Europe, North America, and beyond. The carillon, a keyboard instrument of at least two octaves of precisely tuned bronze bells, played from a mechanical- action keyboard and pedalboard, and usually concealed in a tower, has not received a comprehensive historical treatment since André Lehr’s The Art of the Carillon in the Low Countries (1991). A Dutch bellfounder and campanologist, Lehr contributed a positivist history that was far-ranging and thorough. In 1998, Alain Corbin’s important study Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside (translated from the 1994 French original) approached the broader field of campanology as a history of the senses.1 Belgian carillonneur and musicologist Luc Rombouts has now compiled his extensive knowledge of carillon history in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the United States, as well as of less visible carillon cultures from Curaçao to Japan, into Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music, the most valuable scholarly account of the instrument to date. Rombouts’s original Dutch book, Zingend Brons (Leuven: Davidsfonds, 2010), is the more comprehensive version of the two, directed at a general readership in the Low Countries familiar with carillon music, and at carillonneurs and music scholars. -

HISTORY of the NATIONAL CATHOLIC COMMITTEE for GIRL SCOUTS and CAMP FIRE by Virginia Reed

Revised 3/11/2019 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC COMMITTEE FOR GIRL SCOUTS AND CAMP FIRE By Virginia Reed The present National Catholic Committee for Girl Scouts and Camp Fire dates back to the early days of the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) and the National Catholic Welfare Conference. Although it has functioned in various capacities and under several different names, this committee's purpose has remained the same: to minister to the Catholic girls in Girl Scouts (at first) and Camp Fire (since 1973). Beginnings The relationship between Girl Scouting and Catholic youth ministry is the result of the foresight of Juliette Gordon Low. Soon after founding the Girl Scout movement in 1912, Low traveled to Baltimore to meet James Cardinal Gibbons and consult with him about her project. Five years later, Joseph Patrick Cardinal Hayes of New York appointed a representative to the Girl Scout National Board of Directors. The cardinal wanted to determine whether the Girl Scout program, which was so fine in theory, was equally sound in practice. Satisfied on this point, His Eminence publicly declared the program suitable for Catholic girls. In due course, the four U.S. Cardinals and the U.S. Catholic hierarchy followed suit. In the early 1920's, Girl Scout troops were formed in parochial schools and Catholic women eagerly became leaders in the program. When CYO was established in the early 1930's, Girl Scouting became its ally as a separate cooperative enterprise. In 1936, sociologist Father Edward Roberts Moore of Catholic charities, Archdiocese of New York, studied and approved the Girl Scout program because it was fitting for girls to beome "participating citizens in a modern, social democracy." This support further enhanced the relationship between the Catholic church and Girl Scouting.