Buskin Track and Others, Eight Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data and Information Committee Agenda 9 June 2021 - Agenda

Data and Information Committee Agenda 9 June 2021 - Agenda Data and Information Committee Agenda 9 June 2021 Meeting is held in the Council Chamber, Level 2, Philip Laing House 144 Rattray Street, Dunedin Members: Hon Cr Marian Hobbs, Co-Chair Cr Michael Laws Cr Alexa Forbes, Co-Chair Cr Kevin Malcolm Cr Hilary Calvert Cr Andrew Noone Cr Michael Deaker Cr Gretchen Robertson Cr Carmen Hope Cr Bryan Scott Cr Gary Kelliher Cr Kate Wilson Senior Officer: Sarah Gardner, Chief Executive Meeting Support: Liz Spector, Committee Secretary 09 June 2021 02:00 PM Agenda Topic Page 1. APOLOGIES No apologies were received prior to publication of the agenda. 2. PUBLIC FORUM No requests to address the Committee under Public Forum were received prior to publication of the agenda. 3. CONFIRMATION OF AGENDA Note: Any additions must be approved by resolution with an explanation as to why they cannot be delayed until a future meeting. 4. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Members are reminded of the need to stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as an elected representative and any private or other external interest they might have. 5. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 3 Minutes of previous meetings will be considered true and accurate records, with or without changes. 5.1 Minutes of the 10 March 2021 Data and Information Committee meeting 3 6. OUTSTANDING ACTIONS OF DATA AND INFORMATION COMMITTEE RESOLUTIONS 8 Outstanding actions from resolutions of the Committee will be reviewed. 6.1 Action Register at 9 June 2021 8 7. MATTERS FOR CONSIDERATION 9 1 Data and Information Committee Agenda 9 June 2021 - Agenda 7.1 OTAGO GREENHOUSE GAS PROFILE FY2018/19 9 This report is provided to present the Committee with the Otago Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory FY2018/19 and report. -

Low Cost Food & Transport Maps

Low Cost Food & Transport Maps 1 Fruit & Vegetable Co-ops 2-3 Community Gardens 4 Community Orchards 5 Food Distribution Centres 6 Food Banks 7 Healthy Eating Services 8-9 Transport 10 Water Fountains 11 Food Foraging To view this information on an interactive map go to goo.gl/5LtUoN For further information contact Sophie Carty 03 477 1163 or [email protected] - INFORMATION UPDATED 10 / 2017 - WellSouth Primary Health Network HauoraW MatuaellSouth Ki Te Tonga Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga WellSouth Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga g f e h a c b d Fruit & Vegetable Co-ops All Saints' Fruit & Veges https://store.buckybox.com/all-saints-fruit-vege Low cost fruit and vegetables ST LUKE’S ANGLICAN CHURCH ALL SAINTS’ ANGLICAN CHURCH a 67 Gordon Rd, Mosgiel 9024 e 786 Cumberland St, North Dunedin 9016 OPEN: Thu 12pm - 1pm and 5pm - 6pm OPEN: Thu 8.45am - 10am and 4pm - 6pm ANGLICAN CHURCH ST MARTIN’S b 1 Howden Street, Green Island, Dunedin 9018, f 194 North Rd, North East Valley, Dunedin 9010 OPEN: Thu 9.30am - 11am OPEN: Thu 4.30pm - 6pm CAVERSHAM PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH ST THOMAS’ ANGLICAN CHURCH c Sidey Hall, 61 Thorn St, Caversham, Dunedin 9012, g 1 Raleigh St, Liberton, Dunedin 9010, OPEN: Thu 10am -11am and 5pm - 6pm OPEN: Thu 5pm - 6pm HOLY CROSS CHURCH HALL KAIKORAI PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH d (Entrance off Bellona St) St Kilda, South h 127 Taieri Road, Kaikorai, Dunedin 9010 Dunedin 9012 OPEN: Thu 4pm - 5.30pm OPEN: Thu 10.30am - 1pm * ORDER 1 WEEK IN ADVANCE WellSouth Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga 1 g h f a e Community Gardens Land gardened collectively with the opportunity to exchange labour for produce. -

Flood Hazard of Dunedin's Urban Streams

Flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams Review of Dunedin City District Plan: Natural Hazards Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-478-37680-7 Published June 2014 Prepared by: Michael Goldsmith, Manager Natural Hazards Jacob Williams, Natural Hazards Analyst Jean-Luc Payan, Investigations Engineer Hank Stocker (GeoSolve Ltd) Cover image: Lower reaches of the Water of Leith, May 1923 Flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams i Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Describing the flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams .................................................. 4 2.1 Characteristics of flood events ............................................................................... 4 2.2 Floodplain mapping ............................................................................................... 4 2.3 Other hazards ...................................................................................................... -

General Distribution and Characteristics of Active Faults and Folds in the Clutha and Dunedin City Districts, Otago

General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Clutha and Dunedin City districts, Otago DJA Barrell GNS Science Consultancy Report 2020/88 April 2021 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to Otago Regional Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of or reliance on any contents of this report by any person other than Otago Regional Council and shall not be liable to any person other than Otago Regional Council, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. Use of Data: Date that GNS Science can use associated data: March 2021 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Barrell DJA. 2021. General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Clutha and Dunedin City districts, Otago. Dunedin (NZ): GNS Science. 71 p. Consultancy Report 2020/88. Project Number 900W4088 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... IV 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .....................................................................................................1 1.2 Scope and Purpose .........................................................................................5 2.0 INFORMATION SOURCES ........................................................................................7 -

7 EDW VII 1907 No 48 Taieri Land Drainage

198 1907, No. 48.J Taieri Land Drainage. [7 EDW. VII. New Zealand. ANALYSIS. Title. I 9. Existing special rates. 1. Short Title. i 10. General powers of the Board. 2. Special drainage district constituted. 11. Particular powers of the Board. 3. Board. I 12. Diverting water on to priva.te land. 4. Dissolution of old Boards. 13. Borrowing-powers. 5. Ratepayers list. I 14. Endowment. 6. Voting-powers of ratepayers. I 15. Application of rates. 7. Olassification of land. I 16. Assets and Habilities of old Boa.rds. S. General rate. Schedules. 1907 , No. 48. Title. AN ACT . to make Better Provision for the Drainage of certain Land in Otago. [19th November, 1907. BE IT ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- Short Title. 1. This Act may be cited as the Taieri Land Drainage Act, 1907. Special drainage 2. (1.) The area described in the First Schedule hereto is hereby district constituted. constituted and declared to be a special drainage district to be called the rraieri Drainage District (hereinafter referred to as the district). (2.) Such district shall be deemed to be a district within the meaning of the Land Drainage Act, 1904, and subject to the pro visions of this Act the provisions of that Act shall apply accordingly. (3.) The district shall be subdivided into six subdivisions, with the names and boundaries described in the Second Schedule hereto. (4.) The Board may by special order from time to time alter the boundaries of any such subdivision. -

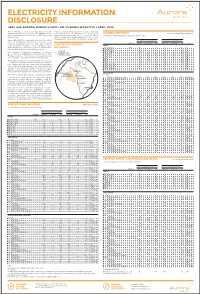

Electricity Information Disclosure Here Are Aurora Energy’S New Line Charges Effective 1 April 2020

ELECTRICITY INFORMATION DISCLOSURE HERE ARE AURORA ENERGY’S NEW LINE CHARGES EFFECTIVE 1 APRIL 2020 Aurora Energy is your local electricity network, this price change will be given in our updated pricing distributing electricity to more than 90,000 homes, methodology, due for publication on our website DUNEDIN NETWORK Supply from South Dunedin and Halfway Bush grid exit points farms and businesses in Dunedin, Central Otago and (www.auroraenergy.co.nz) on, or before, 31 March (Dunedin City excluding Waitati, Waikouaiti, Strath Taieri) Queenstown. 2020. Transmission charges represent 29% of total delivery prices, on average. All charges exclude GST. Aurora Energy’s line charge prices recover the direct Prices effective from 1 Apr 2020 to 31 Mar 2021 Prices effective from 1 Apr 2019 to 31 Mar 2020 costs of distributing electricity to you across our CONNECTIONS DISTRIBUTION PASS-THROUGH TOTAL DISTRIBUTION PASS-THROUGH TOTAL network (Distribution prices), and other indirect ELECTRICITY PRICING costs including incentives, rates, regulatory levies RESIDENTIAL and transmission of electricity across Transpower’s NETWORKS Daily fixed price (15 kVA) 48,109 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 ¢ / day national grid (together, Pass-through prices). Daily fixed price (8 kVA) 532 4.10 4.10 4.10 4.10 ¢ / day DUNEDIN Uncontrolled – summer 8.91 0.41 9.32 6.41 2.41 8.82 ¢ / kWh The Commerce Commission regulates to constrain QUEENSTOWN Uncontrolled – winter 10.12 3.86 13.98 7.28 5.93 13.21 ¢ / kWh the revenues of distribution businesses like Aurora CENTRAL OTAGO All inclusive – summer 4.39 1.14 5.53 3.16 2.33 5.49 ¢ / kWh Energy, to protect the interests of consumers, and All inclusive – winter 6.51 1.65 8.16 4.68 3.55 8.23 ¢ / kWh sets stringent standards for service performance. -

The Early History of New Zealand

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES *f Dr. T. M. Hockkn. THE EARLY HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND. BEING A SERIES OF LECTURES DELIVERED BEFORE THE OTAGO INSTITUTE; ALSO A LECTURETTE ON THE MAORIS OF THE SOUTH ISLAND. By The Late Dr. T. M. Hocken. WELLINGTON, N.Z. JOHN MACKAY, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. I9I4. MEMOIR: DR. THOMAS MORLAND HOCKEN, The British nation can claim the good fortune of having on its roll of honour men and women who stand out from the ranks of their fellows as examples of lofty patriotism and generosity of character. Their fine idea of citizenship has not only in the record of their own lives been of direct benefit to the nation, but they have shone as an example to others and have stirred up a wholesome senti- ment of emulation in their fellows. There has been no lack of illustrious examples in the Motherland, and especially so in the last century or so of her history. And if the Motherland has reason to be proud of her sons and daughters who have so distinguished themselves, so likewise have the younger nations across the seas. Canada, South Africa, Aus- tralia, New Zealand, each has its list of colonists who are justly entitled to rank among the worthies of the Empire, whose generous acts and unselfish lives have won for them the respect and the gratitude of their fellows ; and, as I shall hope to show, Thomas Morland Hocken merits inclusion in the long list of national and patriotic benefactors who in the dominions beyond the seas have set a worthy example to their fellows. -

Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 - Agenda

Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 - Agenda Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 Meeting will be held in the Council Chamber, Level 2, Philip Laing House 144 Rattray Street, Dunedin Members: Cr Andrew Noone, Chairperson Cr Carmen Hope Cr Michael Laws, Deputy Chairperson Cr Gary Kelliher Cr Hilary Calvert Cr Kevin Malcolm Cr Michael Deaker Cr Gretchen Robertson Cr Alexa Forbes Cr Bryan Scott Hon Cr Marian Hobbs Cr Kate Wilson Senior Officer: Sarah Gardner, Chief Executive Meeting Support: Liz Spector, Committee Secretary 25 November 2020 01:00 PM Agenda Topic Page 1. APOLOGIES Cr Deaker and Cr Hobbs have submitted apologies. 2. CONFIRMATION OF AGENDA Note: Any additions must be approved by resolution with an explanation as to why they cannot be delayed until a future meeting. 3. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Members are reminded of the need to stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as an elected representative and any private or other external interest they might have. 4. PUBLIC FORUM Members of the public may request to speak to the Council. 4.1 Mr Bryce McKenzie has requested to speak to the Council about the proposed Freshwater Regulations. 5. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 4 The Council will consider minutes of previous Council Meetings as a true and accurate record, with or without changes. 5.1 Minutes of the 28 October 2020 Council Meeting 4 6. ACTIONS (Status of Council Resolutions) 12 The Council will review outstanding resolutions. 7. MATTERS FOR COUNCIL CONSIDERATION 14 1 Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 - Agenda 7.1 CURRENT RESPONSIBILITIES IN RELATION TO DRINKING WATER 14 This paper is provided to inform the Council on Otago Regional Council’s (ORC) current responsibilities in relation to drinking water. -

Waste for Otago (The Omnibus Plan Change)

Key Issues Report Plan Change 8 to the Regional Plan: Water for Otago and Plan Change 1 to the Regional Plan: Waste for Otago (The Omnibus Plan Change) Appendices Appendix A: Minster’s direction matter to be called in to the environment court Appendix B: Letter from EPA commissioning the report Appendix C: Minister’s letter in response to the Skelton report Appendix D: Skelton report Appendix E: ORC’s letter in responding to the Minister with work programme Appendix F: Relevant sections of the Regional Plan: Water for Otago Appendix G: Relevant sections of the Regional Plan: Waste for Otago Appendix H: Relevant provisions of the Resource Management Act 1991 Appendix I: National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 Appendix J: Relevant provisions of the National Environmental Standards for Freshwater 2020 Appendix K: Relevant provisions of the Resource Management (Stock Exclusion) Regulations 2020 Appendix L: Relevant provisions of Otago Regional Council Plans and Regional Policy Statements Appendix M: Relevant provisions of Iwi management plans APPENDIX A Ministerial direction to refer the Otago Regional Council’s proposed Omnibus Plan Change to its Regional Plans to the Environment Court Having had regard to all the relevant factors, I consider that the matters requested to be called in by Otago Regional Council (ORC), being the proposed Omnibus Plan Change (comprised of Water Plan Change 8 – Discharge Management, and Waste Plan Change 1 – Dust Suppressants and Landfills) to its relevant regional plans are part of a proposal of national significance. Under section 142(2) of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), I direct those matters to be referred to the Environment Court for decision. -

Natural Hazards on the Taieri Plains, Otago

Natural Hazards on the Taieri Plains, Otago Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, 70 Stafford St, Dunedin 9054 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-478-37658-6 Published March 2013 Prepared by: Kirsty O’Sullivan, natural hazards analyst Michael Goldsmith, manager natural hazards Gavin Palmer, director environmental engineering and natural hazards Cover images Both cover photos are from the June 1980 floods. The first image is the Taieri River at Outram Bridge, and the second is the Taieri Plain, with the Dunedin Airport in the foreground. Executive summary The Taieri Plains is a low-lying alluvium-filled basin, approximately 210km2 in size. Bound to the north and south by an extensive fault system, it is characterised by gentle sloping topography, which grades from an elevation of about 40m in the east, to below mean sea level in the west. At its lowest point (excluding drains and ditches), it lies about 1.5m below mean sea level, and has three significant watercourses crossing it: the Taieri River, Silver Stream and the Waipori River. Lakes Waipori and Waihola mark the plain’s western boundary and have a regulating effect on drainage for the western part of the plains. The Taieri Plains has a complex natural-hazard setting, influenced by the combination of the natural processes that have helped shape the basin in which the plain rests, and the land uses that have developed since the mid-19th century. -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

Why Is the Upgrade Needed? How Will the Project Affect Me? Is There a Way

- Ota-kou Voltage Upgrade Project - - We’re improving the power supply to the Otakou area on the - - Otago Peninsula to provide more reliable electricity supplies to How will the project Is there a way to do How is electricity supplied to Otakou? homes, farms and businesses. affect me? this work without an Electricity is transported from generation sources (such as a wind farms and hydro power stations) across the national grid transmission system to the local distribution system then onto consumers. To supply power to the - To upgrade the network safely, we need to turn the outage? Ota-kou area, Aurora Energy takes high voltage electricity from the Transpower substation in Halfway Bush to During March 2015, we’ll be upgrading the voltage supply to power off while we carry out the work. We would the Port Chalmers substation, where it is converted from 33,000 volts (or 33kV) to a lower voltage of 11,000 Unfortunately, no. We have to turn off the power - - - like to advise electricity consumers that electricity volts (11kV). The power is then carried on pylons over the harbour, then along the peninsula to Ota-kou where Otakou from 6,600 volts to 11,000 volts, to enable power to be - - to do the work safely. By making these planned outages are planned in Otakou during March the voltage is lowered again to 6,600 volts (6.6kV) to local transformers that convert it further to 230 volts for improvements, we can improve the future reliability delivered more efficiently. 2015. You will also be individually notified by your use in the home.