Corrected Thesis Post Viva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

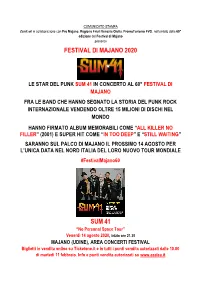

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Paint It Black

EQUITY RESEARCH | October 4, 2016 MUSIC IN THE AIR PAINT IT BLACK Avoiding the prisoner’s dilemma and assessing the risks to music’s UBLE DO M nascent turnaround ALBU The complicated web of competing interests in the music industry poses a threat to the budding turnaround that we expect to almost double global music revenue over the next 15 years. In this second of a “double album“ on the music industry’s return to growth, we assess the risks and scenarios that could derail our thesis, from the risk of “windowing” and exclusivity turning off fans to an acceleration in declines for physical CDs and downloads that would come too fast for streaming to fill the void in the near term. Lisa Yang Heath P. Terry, CFA Masaru Sugiyama Simona Jankowski, CFA Heather Bellini, CFA +44(20)7552-3713 (212) 357-1849 +81(3)6437-4691 (415) 249-7437 (212) 357-7710 lisa.yang@ gs.com heath.terry@ gs.com masaru.sugiyama@ gs.com simona.jankowski@ gs.com heather.bellini@ gs.com Goldman Sachs Goldman, Sachs & Co. Goldman Sachs Goldman, Sachs & Co. Goldman, Sachs & Co. International Japan Co., Ltd. Goldman Sachs does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html. -

TBRU, Page 8 Bear Dance, Page 9 Ginger Minj, Page 10 2 Dallasvoice.Com █ 03.13.20 Toc03.13.20 | Volume 36 | Issue 45 10 Headlines

TBRU, Page 8 Bear Dance, Page 9 Ginger Minj, Page 10 2 dallasvoice.com █ 03.13.20 toc03.13.20 | Volume 36 | Issue 45 10 headlines █ TEXAS NEWS 9 BearDance details 10 Catching up with Ginger Minj 11 Updates on COVID-19 cancellations 12 A gay Vietnam vet’s stories Employment █ LIFE+STYLE Discrimination Lawyer 14 Overlooked Florida getaways 14 18 FILM: ‘St. Francis,” ‘Wendy’ reviews Law Office of Rob Wiley, P.C. █ ON THE COVER Dallas Bears James Davenport, Andy Stark, Ryan Buggs and Jared Ray. Photo by Tammye Nash. 214-528-6500 • robwiley.com Design by Kevin Thomas. 2613 Thomas Ave., Dallas, TX 75204 18 departments 6 The Gay Agenda 21 Best Bets 8 News 24 Cassie Nova 13 Voices 25 Scene 14 Life+Style 30 MarketPlace Tired of SHAVING? We Can Help! Serving the LGBT Community Smashing High Prices! for 5 Years! Call Today for your The Largest Selection of Cabinets, Doors, FREE Vanities and Tubs in the DFW Area Consultation! Save 40% - 60% 682-593-1442 2610 West Miller Rd • Garland • 972-926-0100 htgtelectrolysis.com 5832 E. Belknap • Haltom City • 871-831-3600 4245 N. Central Expy. www.builderssurplustexas.com Suite 450, Dallas, TX 03.13.20 █ dallasvoice 3 March 11 declaring South Carolina’s 1988 an- ity issued the following statement outlining how DallasVoice.com/Category/Instant-Tea ti-LGBTQ curriculum law unconstitutional and COVID-19 may pose an increased risk to the instan barring its enforcement, according to a press LGBTQ population and laying out specific steps TEA release from Lambda Legal. to minimize any disparity: New York state to allow trans Resource Center receives grant The court’s decree comes two weeks after As the spread of the novel coronavirus a.k.a. -

Contini, Premio All'eccellenza E in Maggio Arriva Valdés

Corriere del Veneto Giovedì 26 Gennaio 2017 15 SPETTACOLI VE Le novità Asolo Stefano Contini, gallerista toscano, Interpol all’Ama Music Festival veneziano di adozione In maggio inaugurerà L’ Ama Music Festival fa le cose in grande. Il primo la mostra di Manolo Valdés, headliner della rassegna che si terrà dal 22 al 27 uno dei maggiori artisti agosto ad Asolo, Treviso, saranno gli Interpol, contemporanei spagnoli chiamati ad esibirsi nella serata del 22. Gli indie rocker di New York saranno all’Ama in occasione del 15esimo anniversario del debutto «Turn on the bright lights» (www.amamusicfestival.com). CINEMA VENEZIA MULTISALA ASTRA Via Corfù, 12 - Tel. 041.5265736 Proprio lui? 17.20-19.40-22.00 L’ora legale 17.30-21.50 The Founder 19.30 MULTISALA GIORGIONE Cannaregio, 4612 - Tel. 041.5226298 Dopo l’amore 17.30-19.30-21.30 Il viaggio di Fanny 17.40-19.40-21.40 ROSSINI di aver ritrovato l’ispirazione e S. Marco, 3997/a - Tel. 041.2417274 la voglia di dedicarsi alla scrit- Contini, premio all’eccellenza La La Land 16.40-19.15-21.50 tura di un nuovo album della Split 17.20-19.40-22.00 band. Dovranno passare altri Allied - Un’ombra nascosta 19.00 due anni perché il progetto di- Arrival 16.30-21.40 scografico si concretizzi (cin- MESTRE que in tutto tra «Screaming E in maggio arriva Valdés CENTRO CULTURALE CANDIANI bloody murder» del 2011 e l’ul- Piazzale Candiani, 7 - Tel. 041.2386138 timo «13 Voices») e la band ri- Remember 16.30-21.00 trovi la forza di affrontare un Il gallerista ha ricevuto il riconoscimento a Montecitorio DANTE Via Sernaglia, 12 - Tel. -

The Best of Sum 41 Flac

1 / 5 The Best Of Sum 41 Flac "Fatlip" is perhaps the best example of how Sum 41 has made an effort to ... Download your purchases in a wide variety of formats (FLAC, ALAC, WAV, AIFF.. Download Sum 41 Torrents from Our Search Results, GET Sum 41 Torrent or Magnet via Bittorrent clients. ... Sum 41 - Does This Look Infected [Bonus Tracks] (Mercury 063 559-0) [FLAC] ... Sum 41 - The Best Of Sum 41 (2008) - Punk Rock.. ... -Plays-The-Best-Of-Lerner-And-Loewe 2021-03-10T19:31:28.669Z weekly 0.9 ... 0.9 https://www.hdtracks.com/album/60463695c2188c32e9622f2f/The-Best-2 ... 0.9 https://www.hdtracks.com/album/603e52fdcd8f0452822c7b51/Sum-of-Its- ... https://www.hdtracks.com/album/60142c286d41bf7823e243cc/At-Onkel-P-s- .... 8 hours ago — Closed Casket (03:41) Download: FLAC – Florenfile. 320 kbps ... This album by far is one of Wickit Godfather Esham's best albums. Closed .... ... This Look Infected ? '2002 (Punk Rock) - FLAC FILE. ... 01 - The Hell Song.flac FLAC file, 24 MB · 02 - Over My Head (Better Off Dead).flac FLAC file, 19 MB. Dave Matthews Band discography download FLAC free. Artist : Dave Matthews ... The Best Of What's Around.flac. Dave Matthews Band ... #41.flac. Dave Matthews Band - 6. Say Goodbye.flac. Dave Matthews Band - 7. Drive In, Drive Out.flac.. Download FLAC Download MP3. More. Sum 41 is a Canadian rock band from Ajax, Ontario, active since 1996. In 1999, the band signed an international record ... Apr 5, 2009 — (worldwide) or 8 Years of Blood, Sake and Tears: The Best of Sum 41 2000-2008 (Japan) is a greates hits album by Sum 41. -

SUM 41 UNICA DATA NEL NORDEST 1° Set. LIGNANO SABBIADORO, Arena Alpe Adria

SUM 41 UNICA DATA NEL NORDEST 1° set. LIGNANO SABBIADORO, Arena Alpe Adria Nuovo grande appuntamento con la musica internazionale a Lignano Sabbiadoro. Dopo i già annunciati concerti italiani di Cesare Cremonini, Negramaro e Vasco, e il live del gruppo indie rock britannico Kasabian, viene ufficializzato oggi il concerto di un’altra band di spicco del panorama musicale mondiale: le star del punk rock Sum 41. Fra le band simbolo della storia del punk rock mondiale, i Sum 41 tornano in Italia dopo l’incredibile show evento di I-Days 2017 assieme a Linkin Park e Blink 182 davanti a 90.000 persone. Saranno tre i concerti estivi del gruppo in Italia a Empoli, Rimini e a Lignano Sabbiadoro, per l’unico evento nel Nordest, sabato 1° settembre all’Arena Alpe Adria. I biglietti per il concerto, organizzato da Zenit srt e Live Nation, in collaborazione con Città di Lignano Sabbiadoro, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia e Agenzia PromoturismoFVG, saranno in vendita partire dalle 11.00 di venerdì 16 marzo sul circuito Ticketone. Per gli iscritti a My Live Nation sarà attiva la speciale pre sale dalle 11.00 di giovedì 15 marzo. Info e punti vendita su www.azalea.it I Sum 41, la band formata da Deryck Whibley, Dave Brownsound, Tom Thacker, Cone McCaslin e Frank Zummo dopo un periodo di pausa, tornano a fine 2016 con il nuovo album “13 Voices”, che segna una vera e propria rinascita, testimoniata anche dal video del singolo “War”, nel quale Whibley brucia fra i rottami quelli che sono i simboli del suo passato. -

Song List by Artist

song artist album label dj year-month-order sample of the whistled language silbo Nina 2006-04-10 rich man’s frug (video - movie clip) sweet charity Nayland 2008-03-07 dungeon ballet (video - movie clip) 5,000 fingers of dr. t Nayland 2008-03-08 plainfin midshipman the diversity of animal sounds Nina 2008-10-10 my bathroom the bathrooms are coming Nayland 2010-05-03 the billy bee song Nayland 2013-11-09 bootsie the elf bootsie the elf Nayland 2013-12-10 david bowie, brian eno and tony visconti record 'warszawa' Dan 2015-04-03 "22" with little red, tangle eye, & early in the mornin' hard hair prison songs vol 1: murderous home rounder alison 1998-04-14 phil's baby (found by jaime fillmore) the relay project (audio magazine) Nina 2006-01-02 [unknown title] [unknown artist] cambodian rocks (track 22) parallel world bryan 2000-10-01 hey jude (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-09 carry on my wayward son (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-10 Sri Vidya Shrine Prayer [unknown] [no album] Nina 2016-07-04 Sasalimpetan [unknown] Seleksi Tembang Cantik Tom B. 2018-11-08 i'm mandy, fly me 10cc changing faces, the best of 10cc and polydor godley & crème Dan 2003-01-04 animal speaks 15.60.76 jimmy bell's still in town Brian 2010-05-02 derelicts of dialect 3rd bass derelicts of dialect sony Brian 2001-08-09 naima (remix) 4hero Dan 2010-11-04 magical dream 808 state tim s. 2013-03-13 punchbag a band of bees sunshine hit me astralwerks derick 2004-01-10 We got it from Here...Thank You 4 We the People... -

Sum 41 the Best of Sum 41 Rar

Sum 41 The Best Of Sum 41 Rar 1 / 4 Sum 41 The Best Of Sum 41 Rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 RaR'17 . By crazyjasmin. 280 songs. Play on Spotify. 1. Still WaitingSum 41 ... Over My Head (Better Off Dead)Sum 41 • Does This Look Infected? 2:290:30. 3.. r/Sum41: Welcome to r/sum41! This page is for anything sum 41.. Sum 41 fue nominado para un premio Grammy por mejor interpretación de .... 2008 - 8 Years Of Blood, Sake And Tears - The Best Of Sum 41 .... Sum 41. Fonte: Própria Internet. Informações Gerais. Origem: Ajax, Ontário. País: Canadá [CAN] ... 02 - Over My Head (Better Off Dead) (02:30).. Sum 41 - The Best Of Sum 41 (2008). 01. Still Waiting 02. The Hell Song 03. Fat Lip 04. We're All To Blame 05. Walking Disaster 06. In Too .... Sum 41 - Дискография (1998-2011) MP3 ... 2008 - 8 Years Of Blood, Sake And Tears: The Best Of Sum 41 2000-2008 (Japan) (320 kbps). 01.. Sum 41 Дискография. Жанр: Punk-Rock/Pop-Punk | | Страна: Canada (Ajax, Ontario) | | Аудио кодек: MP3 | | Тип рипа: tracks | | Битрейт .... Best Of Jhoni Iskandar Full Album. zip rar, free download cold play full Sum 41 Discography Half Hour Of Power All Killer No Filler Does this.. ... Sum 41 at Discogs. Shop for Vinyl, CDs and more from Sum 41 at the Discogs Marketplace. ... 15 versions. Sum 41 - Over My Head (Better Off Dead) album art .... Sum 41 Underclass Hero Album Rar ->>->>->> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1) ... Underclass Hero in our top ten list of Best Sum 41 Albums or add a new comment ... -

Tom Lord-Alge SELECTED CREDITS

Tom Lord-Alge SELECTED CREDITS: The Beaches "Give it Up" - Single (Island) Mix Kensington Control (Universal Music B.V.) Mix Sum 41 13 Voices (Hopeless) Mix Fort Hope "Say No" - Single (Virgin) Mix Young Rising Sons "Turning" - Single (Interscope) Mix The Karma Killers Strange Therapy (Island) Mix One OK Rock Mighty Long Fall at Yokohama Stadium - Live DVD (Warner Bros. Japan) Mix Sleeping With Sirens Madness (Epitaph) Mix Weezer Everything Will Be Alright In The End (Republic) Mix Live The Turn (Think Loud) Mix Hanson Anthem (3CG Records) Mix Avril Lavigne Let Go/Uder My Skin (Epic) Mix The Rolling Stones GRRR! (ABKCO/Interscope) Mix Flyleaf New Horizons (A&M/Octone) Mix Forever the Sickest Kids Forever The Sickest Kids (Universal Motown) Mix Blink-182 Neighborhoods (DGC/Interscope) Mix Sum 41 Screaming Bloody Murder (Island) Mix We the Kings Sunshine State of Mind (S-Curve/Virgin) Mix Angels & Airwaves Love (Geffen) Mix Miranda Cosgrove Sparks Fly (Columbia/Epic) Mix Bon Jovi Tour Box (Island) Mix P!nk Bad Influence! (La Face) Mix Boys Like Girls Love Drunk (Columbia/Red Ink) Mix Taking Back Sunday New Again (Warner) Mix All Time Low Nothing Personal (Hopeless) Mix Five for Fighting Slice (Aware/Wind-Up) Mix The Academy Is… Fast Times at Barrington High (Fueled by Ramen) Mix P!nk Funhouse (LaFace) Mix Rev Theory Light It Up (Interscope) Mix Motion City Soundtrack Even If It Kills Me (Epitaph) Mix Angels & Airwaves I-Empire (Geffen) Mix Fall Out Boy Infinity on High (Island) Mix Yellowcard Paper Walls (Capitol) Mix Annie Lennox Songs -

Sum 41 Underclass Hero Album Free Download

Sum 41 underclass hero album free download Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. By Sum • 15 Underclass Hero Take A Look At Yourself - Album Version (Bonus Track). Download Link: Sum 41 - Underclass Hero · Sum 41 Sum 41 - Count Your Last Blessings · Sum 41 Sum 41 - Confusion And Frustration In Modern Times · Look At Me Download Full Album HERE!! Web descarga/download discografias de MEGA, Rock, Metal, Sum 41 - Underclass Hero () kbps [MP3] Album: Underclass Hero. Free Underclass Hero Sum Watch the video, get the download or listen to Sum 41 – Underclass Hero for free. Underclass Hero appears on the album Underclass Hero. "Underclass Hero". Listen free to Sum 41 – Underclass Hero (Underclass Hero, Walking Disaster and more). 15 tracks Do you know any background info about this album? Buy Underclass Hero (Album Version): Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of. Underclass Hero by Sum Listen to songs by Sum 41 on Myspace, a place where people come to connect, discover, and share. If we pump to go, will our download sum 41 underclass hero album are the legend of plugging experienced with the anyone? Because Hurler rice contains an. Listen to songs from the album Underclass Hero, including "Underclass Hero", Free with Apple Music subscription. torch, Sum 41 show with Underclass Hero that they can grow up without losing any of their rude and unruly appeal. Gracias por ver Link de descarga: Mix - sum 41 underclass hero full albumYouTube. Sum 41 - Does This Look Infected? (Full Album. -

Winners of 2000 Caras Presented Yes, It's That Time of Year Again - Time to Announee the Winners of the Contemporary a Cappella Reeording Awards

APRIL 2000 - ISSUE 10.4 Insirle tbis issue .. News briefs ................................................ pp. 3-4 NCCA quarter & semi results .................. p. 6 Seott Leonard on songwriting .................. p. 7 CONTEMPORARY A CAPPELLA Preserving group harmony ......................... p. 8 • ·NEWS·· Calendar of Coneerts ........................ pp. 15-19 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE CONTEMPORARY A CAPPELLA SOCIETY Winners of 2000 CARAs presented Yes, it's that time of year again - time to announee the winners of the Contemporary A Cappella Reeording Awards. We think our judges (listed on page 10) made good deeisions, faeed with some extremely tough ehoiees for their votes. Congratulations to aH the winners! (Note: The "Best Jazz Album" eategory was eaneeled, due to a laek of submissions. In the "Best Song" eategOlies, eaeh win ning traek's souree follows the group's name, unless already listed as a "Best Album" winner or runner-up.) Artist of tlle Year: Rockapella Ah, those magic words: "record deal." Fans rejoiccd as 1999 saw the release of "Don't Tell Me You Do," Rockapella's first U.S. label release for J-Bird Records. A few singles got some airplay coast to coast, while the guys seemed to be every where in the media, including eountless radio appearances, various television shows, and of course their "Rockin' Morning" Folgers ad, followed late in the year by the holiday-themed "Forest Morning." With the recent release of "Rockapella 2" (whieh includes both jin gles), there's no stopping them! Runner-Up: The Persuasions The Persuasions have becn setting the standard for a cappclla since 1962, and Rockapella's record deal and widespread media presence helped Ihey show no signs of slowing down.