Normalizing Intersex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Webbed Penis

Kathmandu University Medical Journal (2010), Vol. 8, No. 1, Issue 29, 95-96 Case Note Webbed penis: A rare case Agrawal R1, Chaurasia D2, Jain M3 1Resident in Surgery, 2Associate Professor, Department of Urology, 3Assistant Professor, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, MLN Medical College, Allahabad (India) Abstract Webbed penis belongs to a rare and little-known defect of the external genitalia. The term denotes the penis of normal size for age hidden in the adjacent scrotal and pubic tissues. Though rare, it can be treated easily by surgery. A case of webbed penis is presented with brief review of literature. Key words: penis, webbed ebbed penis is a rare anomaly of structure of Wpenis. Though a congenital anomaly, usually the patient presents in late childhood or adolescence. Skin of penis forms the shape of a web, covering whole or part of penis circumferentially; with or without glans, burying the penile tissue inside. The length of shaft is normal with normal stretched length. Phimosis may be present. The penis appears small without any diffi culty in voiding function. Fig 1: Penis showing web Fig 2: Markings for double of skin on anterior Z-plasty on penis Case report aspect Our patient, a 17 year old male, presented to us with congenital webbed penis. On examination, skin webs Discussion were present on both lateral sides from prepuce to lateral Webbed penis is a developmental malformation with aspect of penis.[Fig. 1] On ventral aspect, the skin web less than 60 cases reported in literature. The term was present from prepuce to inferior margin of median denotes the penis of normal size for age hidden in the raphe of scrotum. -

12 Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr

K- 12 Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr 1984 Orwell, George 9 10 for Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 3 100 Book Race: Hog Wild in the Reading Room, The Giff, Patricia Reilly 1 1000 Acres, A Knoph, Alfred A. 12 101 Success Secrets for Gifted Kids, The Ultimate Fonseca, Christina 6 Handbook (BOE approved April 2014) 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4 12 Ways to Get to 11 Merriam, Eve 2 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur 6 2002: A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur 6 2061: Odyssey Three Clarke, Arthur 6 26 Fairmount Avenue dePaola, Tomie 2 4 Valentines In A Rainstorm Bond, Felicia 1 5th of March Rinaldi, Ann 5 6 Titles: Eagles, Bees and Wasps, Alligators and Crocodiles, Morgan, Sally 1 Giraffes, Sharks, Tortoises and Turtles 79-Squares Bosse, Malcolm 6 A Likely Place Fox, Paula 4 A Night to Remember Lord, Waler 6 A Nightmare in History: The Holocaust 1933-1945 Chaikin, Miriam 5 A, My Name Is Alice Bayer, Jane 2 Abandoned Puppy Costello, Emily 3 Abby My Love Irwin, Hadley 6 ABC Bunny, The Gag, Wanda 1 Abe Lincoln Goes to Washington Harness, Cheryl 2 Abe Lincoln Grows Up Sandburg, Carl 6 Updated November 11, 2016 *previously approved at higher grade level 1 K- 12 Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 2 Abel's Island Steig, William 3 Abigail Adams, Girl of Colonial Days Wagoner, Jean Brown 2 Abraham Lincoln Cashore, Kristen 2 Abraham Lincoln, Lawyer, Leader, Legend Fontes, Justine & Ron 2 Abraham Lincoln: Great Man, Great Words Cashore, Kristen 5 Abraham Lincoln: Our 16th President Luciano, Barbara L. -

Background Note on Human Rights Violations Against Intersex People Table of Contents 1 Introduction

Background Note on Human Rights Violations against Intersex People Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 2 Understanding intersex ................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Situating the rights of intersex people......................................................................... 4 2.2 Promoting the rights of intersex people....................................................................... 7 3 Forced and coercive medical interventions......................................................................... 8 4 Violence and infanticide ............................................................................................... 20 5 Stigma and discrimination in healthcare .......................................................................... 22 6 Legal recognition, including registration at birth ............................................................... 26 7 Discrimination and stigmatization .................................................................................. 29 8 Access to justice and remedies ....................................................................................... 32 9 Addressing root causes of human rights violations ............................................................ 35 10 Conclusions and way forward..................................................................................... 37 10.1 Conclusions -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

![Springer MRW: [AU:0, IDX:0]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3905/springer-mrw-au-0-idx-0-323905.webp)

Springer MRW: [AU:0, IDX:0]

Pre-Testicular, Testicular, and Post- Testicular Causes of Male Infertility Fotios Dimitriadis, George Adonakis, Apostolos Kaponis, Charalampos Mamoulakis, Atsushi Takenaka, and Nikolaos Sofikitis Abstract Infertility is both a private and a social health problem that can be observed in 12–15% of all sexually active couples. The male factor can be diagnosed in 50% of these cases either alone or in combination with a female component. The causes of male infertility can be identified as factors acting at pre-testicular, testicular or post-testicular level. However, despite advancements, predominantly in the genetics of fertility, etiological factors of male infertility cannot be identi- fied in approximately 50% of the cases, classified as idiopathic infertility. On the other hand, the majority of the causes leading to male infertility can be treated or prevented. Thus a full understanding of these conditions is crucial in order to allow the clinical andrologist not simply to retrieve sperm for assisted reproduc- tive techniques purposes, but also to optimize the male’s fertility potential in order to offer the couple the possibility of a spontaneous conceivement. This chapter offers the clinical andrologist a wide overview of pre-testicular, testicular, and post-testicular causes of male infertility. F. Dimitriadis Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece e-mail: [email protected] G. Adonakis • A. Kaponis Department of Ob/Gyn, School of Medicine, Patras University, Patras, Greece C. Mamoulakis Department of Urology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Crete, Greece A. Takenaka Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Tottori University, Yonago, Japan N. Sofikitis (*) Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Ioannina University, Ioannina, Greece e-mail: [email protected] # Springer International Publishing AG 2017 1 M. -

FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA START TIME Duration min:sec Public Affairs Issue 1 Public Affairs Issue 2 Show & Narrative 1/2/2017 TAKE TWO: The Binge– 2016 was a terrible year - except for all the awesome new content that was Entertainment Industry available to stream. Mark Jordan Legan goes through the best that 2016 had to 9:42 8:30 offer with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: The Ride 2017– 2017 is here and our motor critic, Sue Carpenter, Transportation puts on her prognosticator hat to predict some of the automotive stories we'll be talking about in the new year 9:51 6:00 with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Presidents and the Press– Presidential historian Barbara Perry says contention between a President Politics Media and the news media is nothing new. She talks with Alex Cohen about her advice for journalists covering the 10:07 10:30 Trump White House. TAKE TWO: The Wall– Political scientist Peter Andreas says building Trump's Immigration Politics wall might be easier than one thinks because hundreds of miles of the border are already lined with barriers. 10:18 12:30 He joins Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Prison Podcast– A podcast Law & is being produced out of San Quentin Media Order/Courts/Police State Prison called Ear Hustle. We hear some excerpts and A Martinez talks to 10:22 9:30 one of the producers, Nigel Poor. TAKE TWO: The Distance Between Us– Reyna Grande grew up in poverty in Books/ Literature/ Iguala, Mexico, left behind by her Immigration Authors parents who had gone north looking for a better life and she's written a memoir for young readers. -

The Evolution of Intersex Rights in Russia and Reframing Law and Tradition to Advance Reform

Meyers Final Note (Do Not Delete) 5/24/2019 1:55 PM “Tragic and Glorious Pages”: The Evolution of Intersex Rights in Russia and Reframing Law and Tradition to Advance Reform MAGGIE J. MEYERS* I. INTRODUCTION “Despite all the achievements of civilization, the human being is still one of the most vulnerable creatures on earth.” - Vladimir Putin1 “You are alone, you are not normal”; that is how Aleksander Berezkin learned he was intersex.2 Born in 1984 in Novokuznetsk—a steel-producing town in southwestern Siberia, not unlike Pittsburgh in terms of climate and local economy3—Aleksander lived the life of an ordinary boy until his adolescence, when puberty failed to arrive. “When I was at school, my body looked visibly different from other teenagers,” Aleksander recalled.4 “I had no muscles . [n]o hair on the face. I was skinny and tall. With narrow shoulders and wide hips. Breast glands were enlarged. Sometimes people took me for a girl. I have been bullied and humiliated.”5 Desperate for answers and relief from the merciless taunting and social ostracism, at the age of seventeen Aleksander submitted to a genetic test that revealed the truth. While typical males have the chromosomes XY, Aleksander’s were XXY; he was diagnosed with a variation of Klinefelter syndrome, in which an extra X chromosome inhibits the body’s production of testosterone and leads to the development of stereotypically feminine traits in males.6 But Aleksander received little comfort from his intersex diagnosis, nor Copyright © 2019 by Maggie J. Meyers. * Duke University School of Law, J.D. -

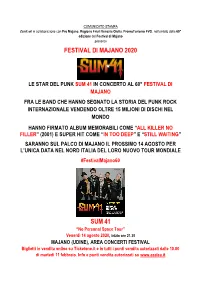

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A

FOR SEXUAL PERVERSION See PARAPHILIAS: Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A. Adler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 5/8/2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library and Information Studies Louise Robbins, Professor, Library and Information Studies A. Finn Enke, Associate Professor, History, Gender and Women’s Studies Helen Kinsella, Assistant Professor, Political Science i Table of Contents Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................iii List of Figures........................................................................................................................vii Crash Course on Cataloging Subjects......................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Setting the Terms: Methodology and Sources.......................................................5 Purpose of the Dissertation..........................................................................................6 Subject access: LC Subject Headings and LC Classification....................................13 Social theories............................................................................................................16 -

Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations of Children with Variations of Sex Anatomy

Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations Of Children With Variations Of Sex Anatomy NGO Report (for Session) to the 5th and 6th Report of Argentina on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) Compiled by: Justicia Intersex (Intersex Human Rights NGO) Mauro Cabral Grinspan justiciaintersex_at_gmail.com http://justiciaintersex.blogspot.com/ Brújula Intersexual (International Intersex Human Rights NGO) Laura Inter brujulaintersexual_at_gmail.com https://brujulaintersexual.org/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Brujulaintersex/ Twitter: @brujulaintersex Brújula Intersexual Argentina (Intersex Human Rights NGO) Gaby González Ch Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/brujulaintersexargentina/ StopIGM.org / Zwischengeschlecht.org (International Intersex Human Rights NGO) Markus Bauer Daniela Truffer Zwischengeschlecht.org P.O.Box 2122 CH-8031 Zurich info_at_zwischengeschlecht.org http://Zwischengeschlecht.org/ http://StopIGM.org/ April 2018 This NGO Report online: http://intersex.shadowreport.org/public/2018-CRC-Argentina-Intersex-Justicia-Brujula-StopIGM_v2.pdf 2 Executive Summary All typical forms of IGM practices are still practised in Argentina today, facilitated and paid for by the State party via the Universal Health Care System under the oversight of the Argentinian Ministry of Health. Parents and children are misinformed, kept in the dark, sworn to secrecy, kept isolated and denied appropriate support. Argentina is thus in breach of its obligations under CRC to (a) take effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent harmful practices on intersex children causing severe mental and physical pain and suffering of the persons concerned, and (b) ensure access to redress and justice, including fair and adequate compensation and as full as possible rehabilitation for victims, as stipulated in CRC art. -

1. Introduction

1. Introduction ‘Intersex’ has always been a contested category, and hence providing a definition of the term and the concept is a challenging task. Intersex activist Michelle O’Brien contends that when speaking or writing about intersex, “the first thing that has to be understood is that the definition of intersex has changed and has become increasingly policed by people with medical, activist and academic careers” (O’Brien 2009). Morgan Holmes, intersex activist and scholar, likewise argues that “intersex is not one but many sites of contested being [that] is hailed by specific and competing interests, and is a sign constantly under erasure, whose significance always carries the trace of an agenda from somewhere else” (Holmes 2009: 2). The shifting processes of signification and resignification of ‘intersex’ that have occurred throughout the centuries, but most considerably in the last two decades, need to be taken into account and are indispensable for an adequate understanding of intersex. Yet in order for intersex individuals and (an) intersex collective(s) to become recognizable, to be socioculturally acknowledged, and to act as a political agent, intersex organizations have developed a working definition of intersex. The Organization Intersex International (OII)1 provides the following definition that is currently in use and widely accepted by global intersex activists, NGOs, and generally by other medical and political agents involved in intersex debates (although their own respective definitions of intersex may differ): “Intersex people are born with physical, hormonal or genetic features that are neither wholly female nor wholly male; or a combination of female and male; or neither female nor male” (OII Australia 2013).2 Implied in this definition is the acknowledgment that various forms of intersex exist, hence intersex is to be understood as comprising a spectrum of 1 The Organization Intersex International (OII) is currently the largest global network of intersex organizations with branches in a dozen countries on five continents. -

Sex, Health, and Athletes

ANALYSIS bmj.com/podcast Ж Listen to a podcast interview with the authors of this analysis article Sex, health, and athletes Recent policy introduced by the International Olympic Committee to regulate hyperandrogenism in female athletes could lead to unnecessary treatment and may be unethical, argue Rebecca Jordan-Young, Peter Sönksen, and Katrina Karkazis he International Olympic Committee nations, Semenya said, “I have been subjected to Caster Semenya: questions about gender (IOC) and international sports federa- unwarranted and invasive scrutiny of the most tions have recently introduced policies intimate and private details of my being.”7 to have significantly higher testosterone levels requiring medical investigation of Intended to improve the handling of such cases, than either non-elite athletes (as measured by women athletes known or suspected these policies have nevertheless generated con- saliva13) or non-athletes.14 The only large scale Tto have hyperandrogenism. Women who are troversy.3 8-10 Most of the debate, however, has study of testosterone in elite athletes showed that found to have naturally high testosterone levels focused on questions of fairness, such as the logic 11 of 234 (5%) of elite female athletes sampled and tissue sensitivity are banned from competi- of using testosterone levels as grounds for exclu- immediately after competition had testosterone tion unless they have surgical or pharmaceutical sion while allowing all other natural variations values >10 nmol/L, and 32 (14%) had a testos- interventions to lower their testosterone levels.1 2 among athletes that affect performance, rather terone level >2.7 nmol/L, the upper limit of the Sports authorities have argued that women than the medical justification.